Fossil evidence of complex multicellular organisms is first observed in rocks deposited 579–555 million years ago.

In Chapter 23, we noted that phylogenies based on living organisms make predictions about the fossil record. Characters and groups associated with lower branches in phylogenies should appear as earlier fossils than those associated with later branches. Although fossils don’t preserve molecular features, the record supports the phylogenetic pattern shown in Fig. 28.12.

Page 590

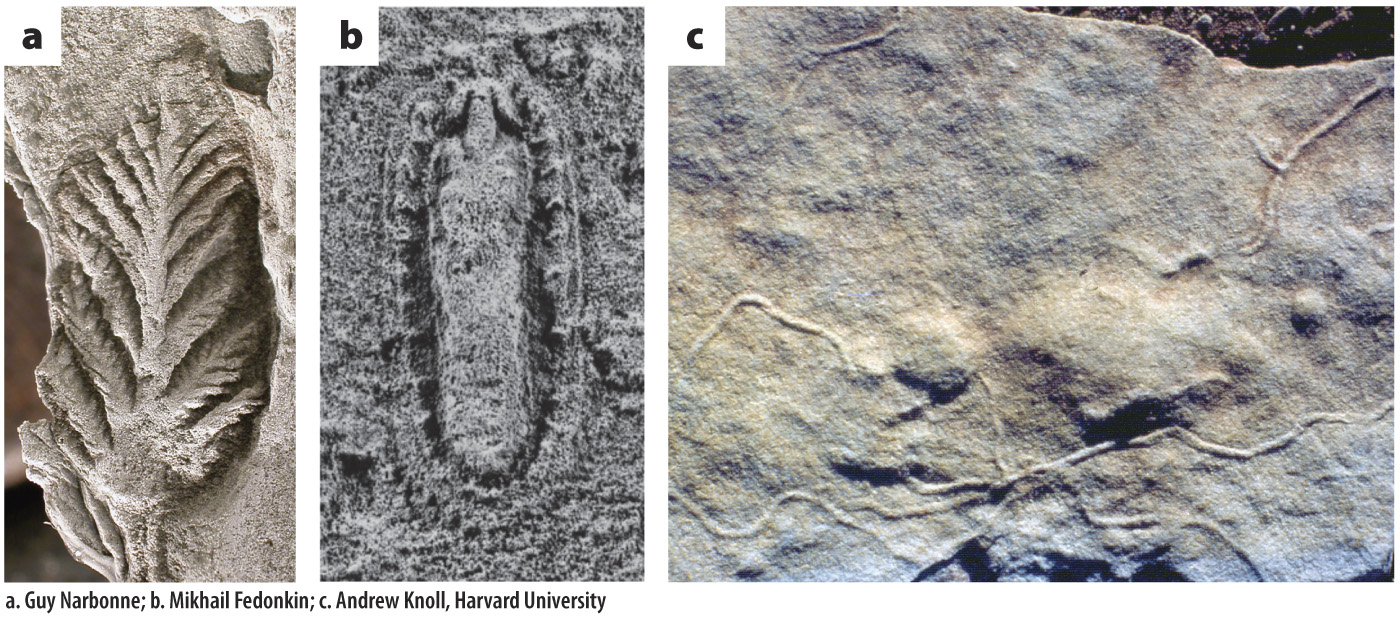

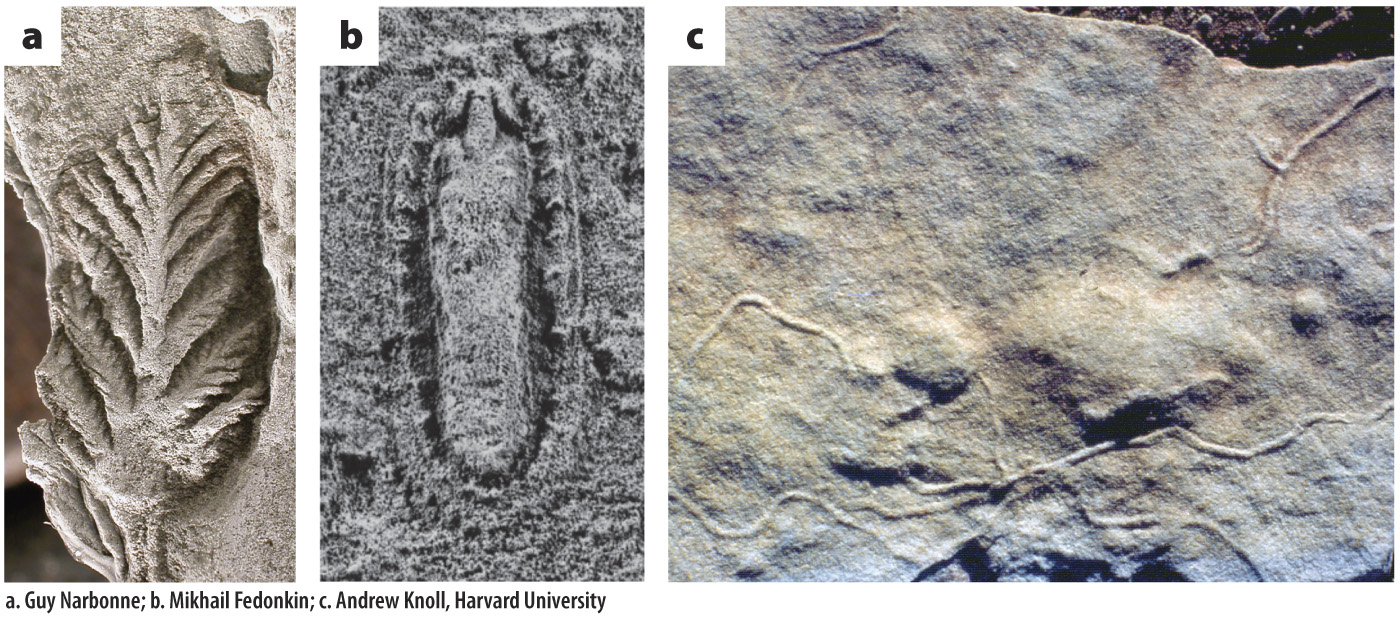

Single-celled protists are found in sedimentary rocks as old as 1800 million years, and a number of simple multicellular forms have been discovered that are nearly as old (see Fig. 27.23). Nonetheless, the oldest fossils that record complex multicellularity are found in rocks that were deposited only 579–555 million years ago. Fig. 28.13a shows one of the oldest known animal fossils, a frondlike form preserved in 575-million-year-old rocks from Newfoundland, near the eastern tip of Canada. This fossil and many others found in rocks of this age are enigmatic. There is complex morphology to be sure, but it is difficult to understand these forms by comparing them to the body plans of living animals. The Newfoundland fossils show no evidence of head or tail, no limbs, and no opening that might have functioned as a mouth. They appear to be very simple organisms that gained both carbon and oxygen by diffusion. These fossils are long and wide, but they are not thick. In fact, it is likely that active metabolism occurred only along the surfaces of these structures.

FIG. 28.13 The earliest fossils of animals. (a) Among the oldest known macroscopic animal fossils is a frond-like form made up of tubular structures, preserved in 575-million-year-old rocks from Newfoundland. (b) The oldest known animal fossil showing bilateral symmetry is a mollusk-like form preserved in 560–555-million-year-old rocks from northern Russia. (c) The oldest tracks and trails of mobile animals are found in rocks 560 million years old and younger.

Such animals lie near the base of the animal tree (Chapter 44), and probably would have developed under the guidance of regulatory genes similar to those present in modern sponges or, perhaps, jellyfish. By 560–555 million years ago, more complex animals, with distinct head and tail, top and bottom, left and right, enter the record (Fig. 28.13b). At the same time, we begin to see tracks and trails made by animals whose muscles enabled them to move across and through surface sediments (Fig. 28.13c), an indirect but complementary record of increasing animal complexity. These, then, are the first known occurrences of the types of animal that dominate ecosystems today, both in the sea and on land. These animals must have possessed a diverse array of genes to guide development, something akin to those seen today in insects or snails.

Clearly, by 579–555 million years ago, the animal tree was beginning to branch. This, however, raises a new question: Why did complex multicellular animals appear so much later than simple multicellular organisms?