Symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria supply nitrogen to both plants and ecosystems.

Nitrogen is the nutrient that plants must acquire in greatest abundance from the soil, and in many ecosystems nitrogen is the nutrient that most limits growth. Nitrogen itself is not rare; 78% of Earth’s atmosphere is nitrogen gas (N2). However, as discussed in Chapter 26, plants and other eukaryotic organisms cannot use N2 directly. Only certain bacteria and archaeons have the metabolic ability to convert N2 into a biologically useful compound in nitrogen fixation. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria transform N2 into forms such as ammonia (NH3) that can be used to build proteins, nucleic acids, and other compounds. Some of these usable forms of nitrogen are released into the soil, where they are available to plants and other organisms.

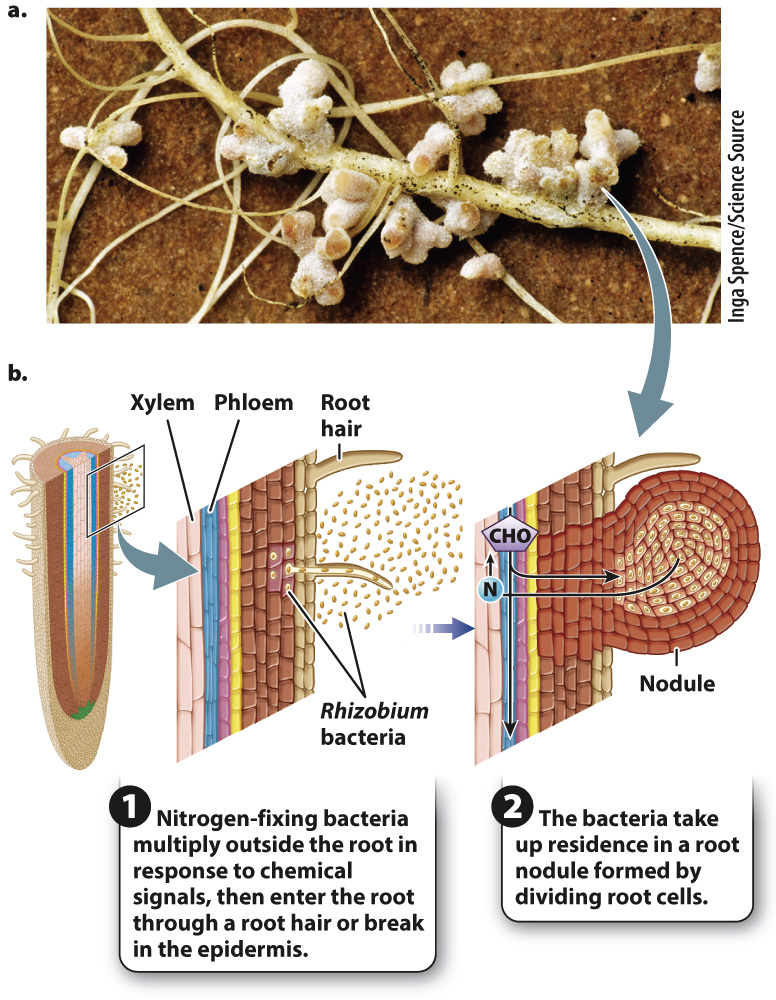

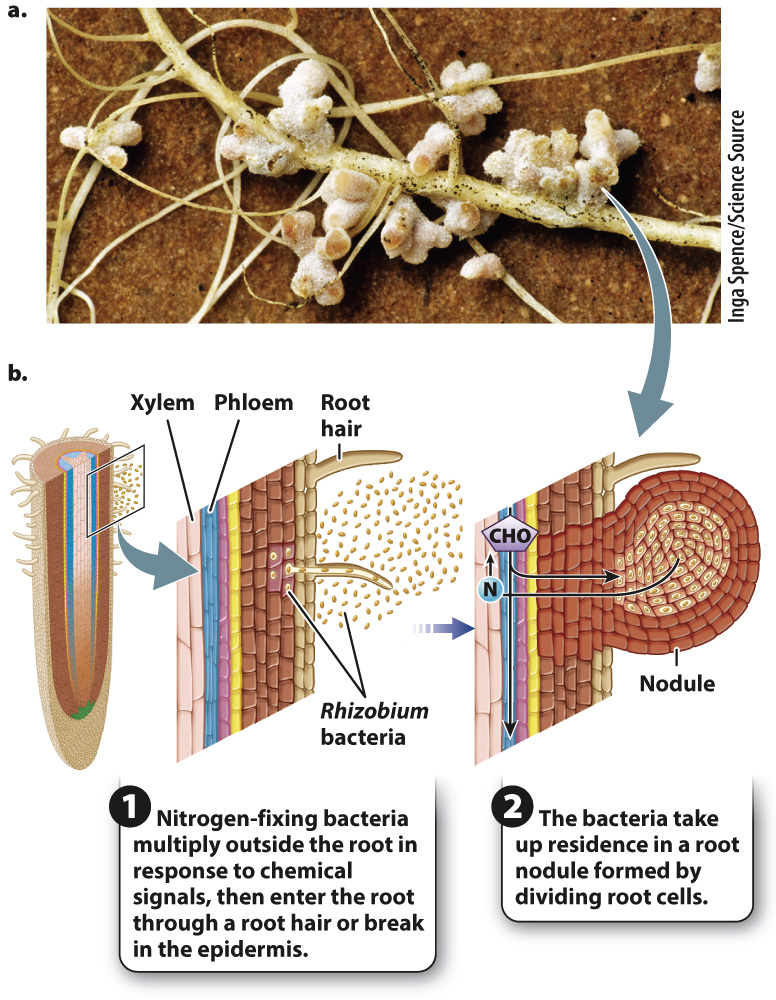

Although many nitrogen-fixing bacteria live freely in the soil, some live in plant roots. When the level of available soil nitrogen is low, some plants form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria (Fig. 29.19). In response to chemical signals transmitted between the root and bacteria, bacteria multiply within the rhizosphere. At the same time, root cells begin dividing, leading to the formation of a pea-sized protrusion called a root nodule. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria enter the root either through root hairs or through breaks in the epidermis. They then move into the center of the nodule and begin to fix nitrogen. Even though the bacteria appear to have taken up residence within the cytoplasm of nodule cells, in fact each bacterial cell is contained within a membrane-bound vesicle produced by the host plant cell.

FIG. 29.19 Symbiosis between roots and nitrogen-fixing bacteria. (a) Symbiotic root nodules on alfalfa; (b) the formation of a root nodule.

The plant supplies its nitrogen-fixing partners with carbohydrates transported by the phloem and carries away the products of nitrogen fixation in the xylem. As in mycorrhizal symbioses, the carbon cost to the plant is high: It is estimated that as much as 25% of the plant’s total carbohydrate goes to nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Relatively few plant species have evolved symbiotic associations with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, but those that have—especially members of the legume (bean) family—provide an important way in which biologically available nitrogen enters into ecosystems. In addition, nitrogen fixation in legume roots helps to sustain fertility in many agricultural systems.