The formation of new root apical meristems allows roots to branch.

Compared to stems, roots branch extensively. Even a plant that has only a single stem aboveground will have many tens of thousands of elongating root tips. A major reason that roots branch so much is that most of the water and nutrients are taken up in a zone near the root tip where root hairs are most abundant. Thus, branching is necessary to create enough root surface area to supply the water and nutrient needs of the shoot.

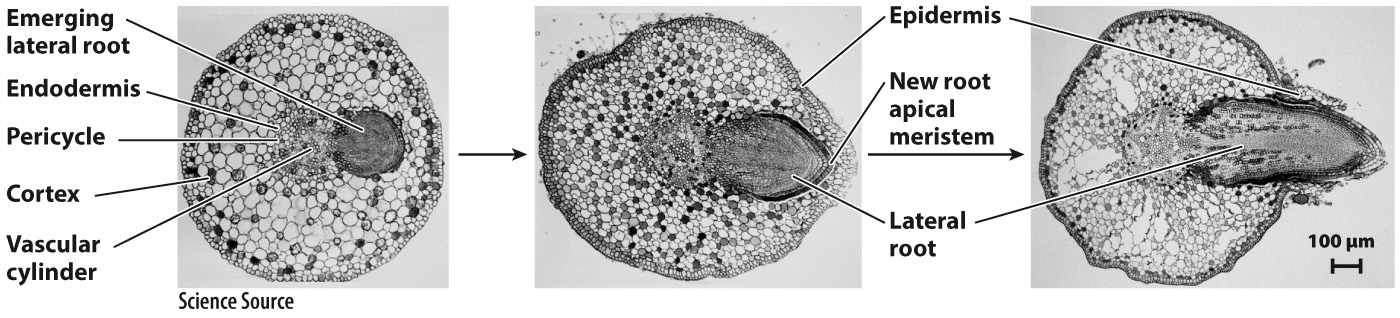

For a root to branch, a new root apical meristem must be formed. In roots, new meristems develop from the pericycle, a single layer of cells just inside the endodermis (Fig. 31.17). The pericycle is immediately adjacent to the vascular bundle, so the new root is connected to the vascular system from the beginning. Because the new root meristem develops internally, the new root must grow through the endodermis, cortex, and epidermis before reaching the soil.

One consequence of initiating new root meristems from the pericycle is that new roots can form anywhere along the root. As a result, plants have tremendous flexibility in the development of their root systems and roots can proliferate locally in response to nutrient abundance. For example, the presence of nitrate, the most common form of nitrogen in soil, triggers the formation of lateral roots. Only a relatively small number of a plant’s roots, however, continue to elongate and branch indefinitely. Most new roots are active for only a short time, after which they die and are shed. This turnover of fine roots allows the root system to respond to changes in the availability of water and nutrients but represents a major expenditure of carbon and energy.

Up to this point, we have described how new roots form from existing roots. New roots can also be produced by stems. Many plants that lack secondary growth produce horizontal stems that grow on or beneath the soil surface. In these plants, new roots form at each successive node, so the uptake capacity of the root system is directly coupled to the elongation of the stem.

When the stem of a plant is severed, new roots often form at the cut end. The formation of new root meristems is stimulated by auxin, which is produced by the young leaves and accumulates by polar transport at the cut end. Because their cut stems can form new roots, plants are able to survive damage and in some cases even proliferate afterward. Many commercially important plants are propagated through cut stems.

Quick Check 3 How is root development similar to and how is it different from stem development?

Quick Check 3 Answer

Both roots and stems grow from apical meristems, have regions of cell division, elongation, and differentiation, and respond to light and gravity. However, root apical meristems are covered by a root cap, the root has a single vascular bundle in the center, and branching occurs by the formation of new meristems from the pericycle; all these features are different from what is seen in stems.