Chapter 32 Introduction

CHAPTER 32

Plant Defense

Keeping the World Green

Core Concepts

- Plants have evolved mechanisms to protect themselves from infection by pathogens, which include viruses, bacteria, fungi, worms, and even parasitic plants.

- Plants use chemical, mechanical, and ecological defenses to protect themselves from being eaten by herbivores.

- The production of defenses is costly, resulting in trade-offs between protection and growth.

- Interactions among plants, pathogens, and herbivores contribute to the origin and maintenance of plant diversity.

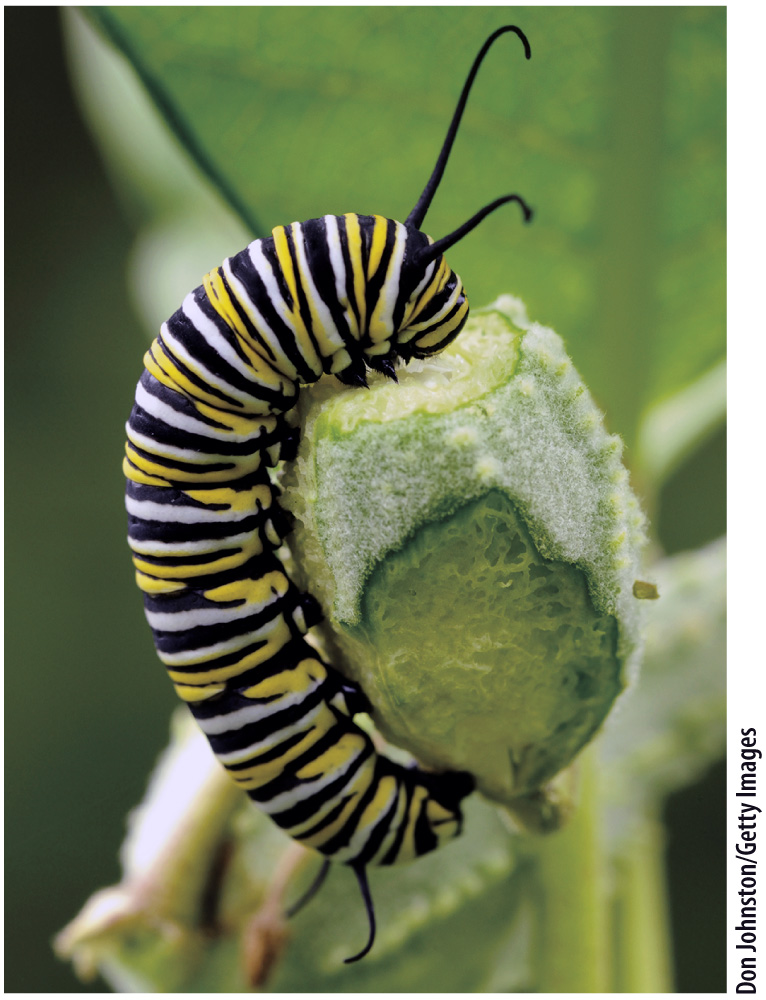

Plants have complicated interactions with animals. As we saw in Chapter 30, many plants rely on animals for pollination or seed dispersal. In return, plant seeds provide a rich source of food for animals, and leaves furnish a vast, but lower-

Plants can’t run away and hide as animals can. Nonetheless, they can sense danger and they are able to deploy a diverse and powerful defensive arsenal that includes physical and chemical deterrents as well as aerial surveillance, armed guards, and sticky traps.

Plants produce a wide array of chemicals that alter the metabolism and influence the behavior of animals that seek to consume them. These molecules also interact with our own biochemistry, and so compounds derived from plants have been used since antiquity as sources of medicine. Our early ancestors turned to the leaves and bark of willow trees in much the same way that we rely on aspirin—