Plants use mechanical and chemical defenses to avoid being eaten.

Milkweeds (Asclepias species) are commonly found in open fields and roadsides across North America. They illustrate well how plants protect themselves from herbivorous animals. In fact, most generalist herbivores, which eat a diversity of plants, do not use milkweeds as a food source. Only specialists, such as caterpillars of the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus), can feed on these well-

In part, milkweed’s defenses are mechanical. The leaves of many milkweed species are covered with dense hairs. An insect crawling on a leaf must make its way through as many as 3000 hairs per square centimeter, a journey likely more daunting to an insect than wading into a blackberry thicket is to a human. Monarch caterpillars may spend as much as an hour mowing off these hairs before they begin to feed. This long handling time represents a significant cost. To understand why monarch caterpillars make this investment, let’s look at milkweed’s other defenses.

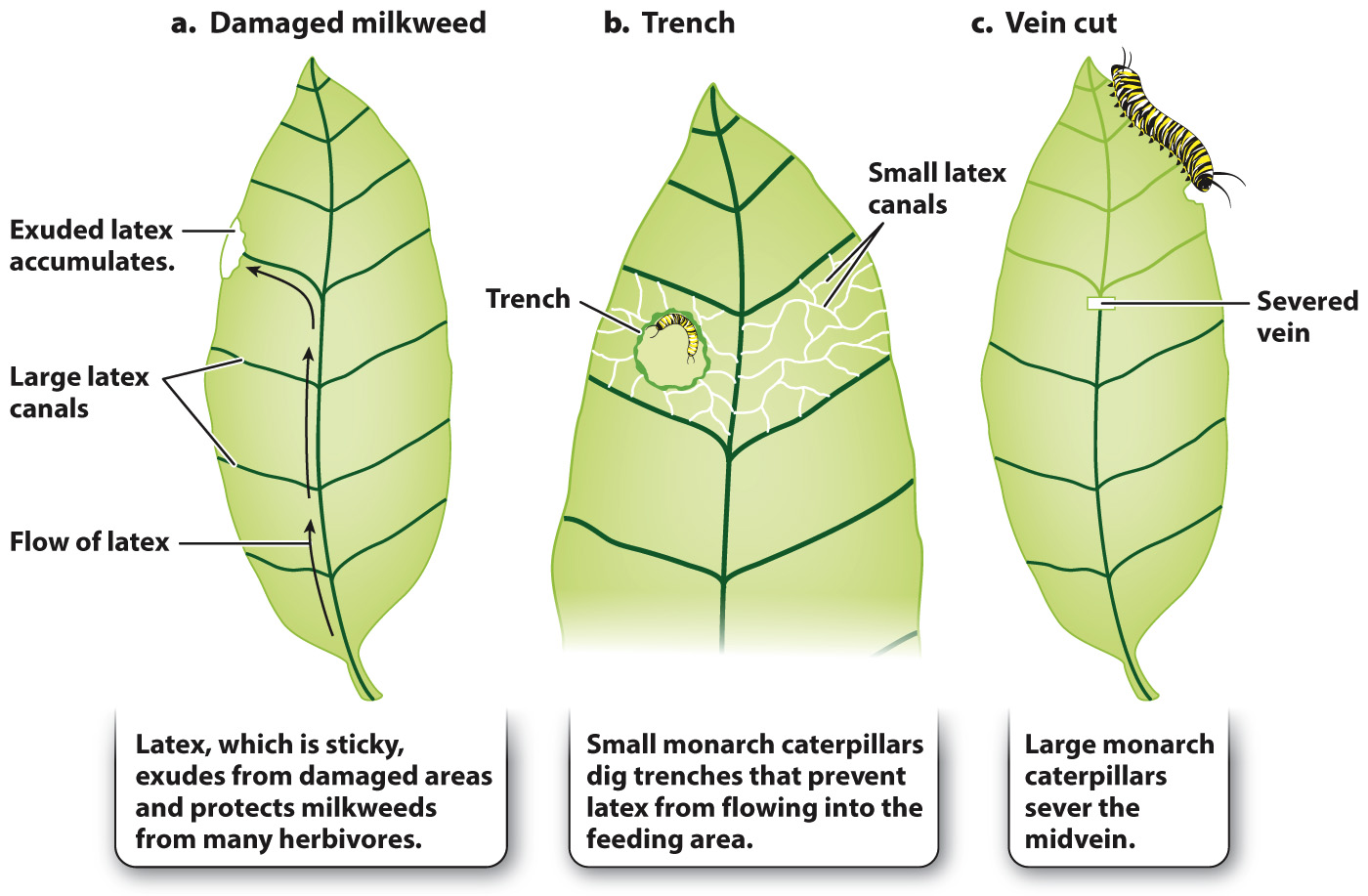

A network of extracellular canals filled with a white, sticky liquid called latex runs through the milkweed leaf, both within the major veins and extending into the regions between veins (Fig. 32.10). Latex canals are under pressure in the intact leaf. Thus, when the leaf is damaged, the latex flows out, sticking to everything it comes into contact with and rapidly congealing on exposure to air. A feeding insect is in danger of having its tiny mouthparts glued together, with potentially fatal consequences. Small monarch caterpillars cut trenches into the leaf that prevent latex from flowing onto the region where they are feeding. Larger caterpillars sever the midvein, relieving the pressure within the latex canals downstream of the cut. The caterpillars are then able to feed without risk on the part of the leaf that lies beyond the severed midvein.

Milkweed latex is not only sticky but also toxic. In particular, milkweed latex contains high concentrations of cardenolides, steroid compounds that cause heart arrest in animals. (In small doses, these compounds are used to treat irregular heart rhythms in humans.) Monarch caterpillars do not metabolize the cardenolides that they consume, but instead sequester them within specific regions of their bodies as a chemical defense against their own predators. Because of the presence of these cardenolides, monarch caterpillars and even the adult butterflies are highly toxic to most birds and other animals that would otherwise eat them. The protection conferred by these chemicals helps explain why monarch caterpillars have evolved to feed on leaves that are both metabolically difficult and time-

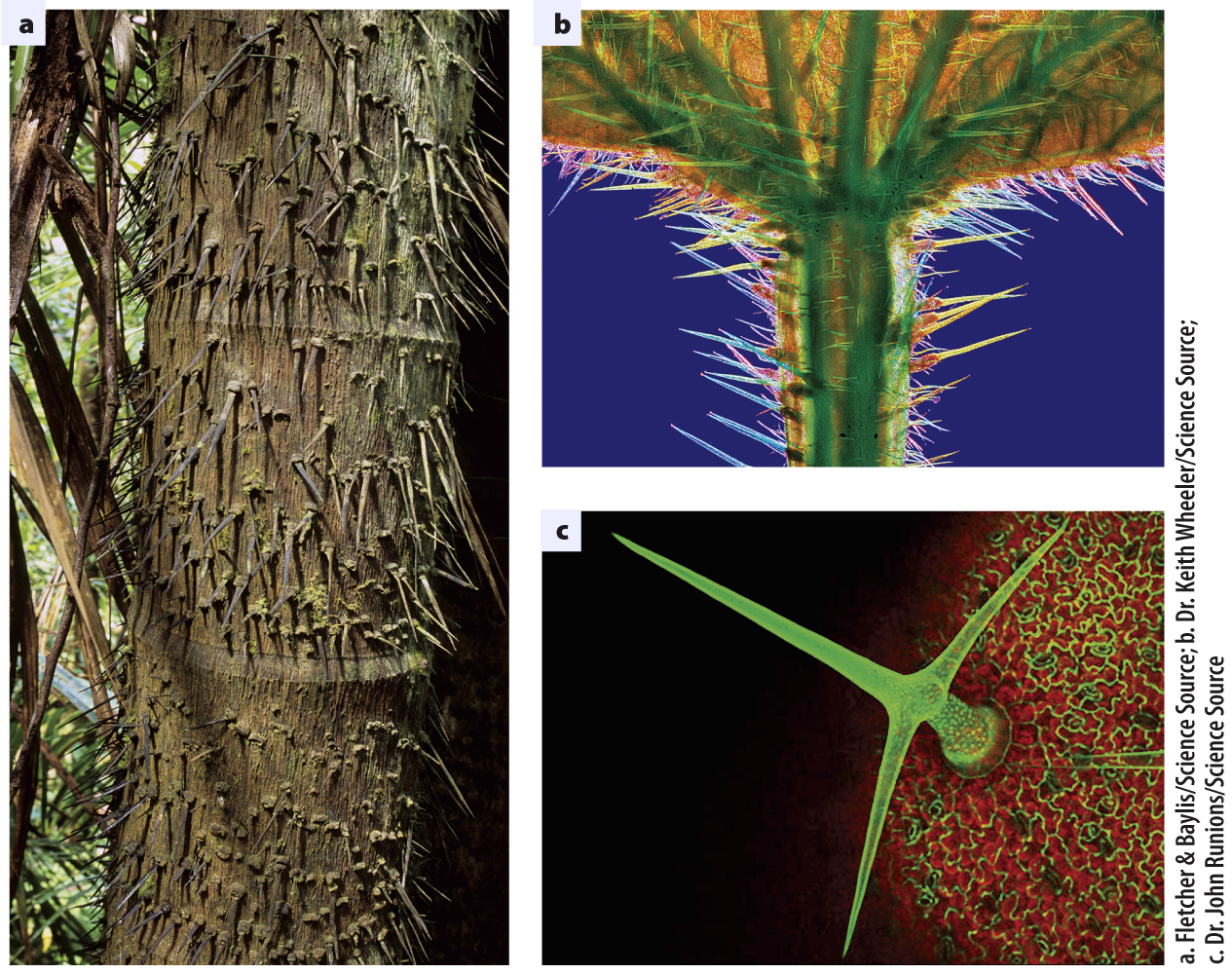

Most plant species have mechanical or chemical defenses against herbivores, or even both. Mechanical defenses are varied. Hairs are common on leaves, and, as anyone who has ever rubbed against a stinging nettle knows, these hairs are sometimes armed with chemical irritants. Grasses and some other plants have a hard, mineral defense consisting of silica (SiO2) plates formed within epidermal cells. Silica wears down insect mouthparts, so the insects feed less efficiently and grow more slowly. On a larger scale, some tropical trees have prickles, spines, or thorns (Fig. 32.11). Even something as simple as how tough a leaf is can have a large impact on the probability of the leaf’s being eaten. In fact, leaves are most likely to be eaten while they are still growing and their tissues not fully hardened. Nonetheless, the most spectacular diversity in plant defenses lies in the realm of chemistry.