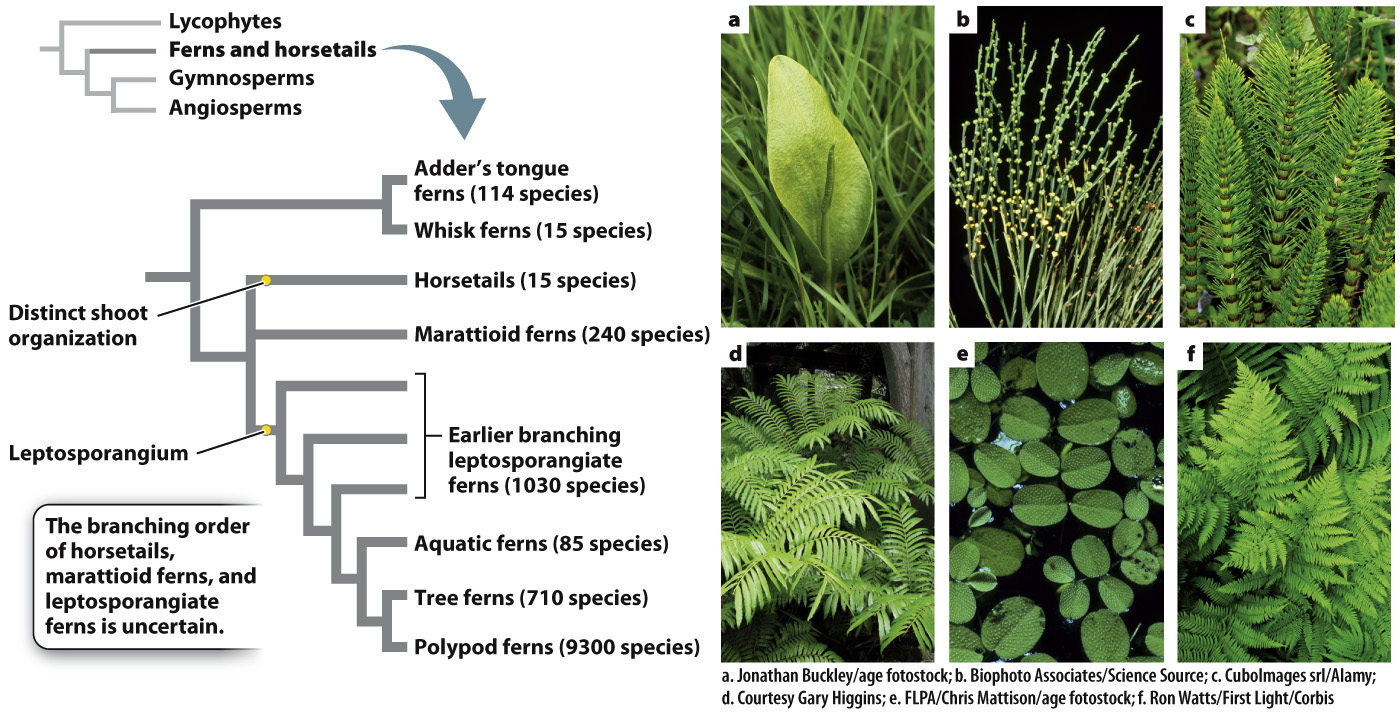

Ferns and horsetails are morphologically and ecologically diverse.

Ferns and horsetails form a monophyletic group that is the sister group to the seed plants (Fig. 33.11). The majority of species in this group are ferns. You can recognize ferns by their distinctive leaves that uncoil during development from tightly wound “fiddleheads” (Fig. 33.12). This group also includes horsetails and whisk ferns, which traditionally were considered distinct groups because of their unique body organizations. Whisk ferns have photosynthetic stems without leaves and roots (see Fig. 33.11b). Thus, they look similar to fossils of early vascular plants. Molecular sequence comparisons, however, support the hypothesis that whisk ferns are the simplified descendants of plants that produced both leaves and roots.

The horsetails, represented by 15 living species of the genus Equisetum, produce tiny leaves arranged in whorls, giving the stem a jointed appearance (see Fig. 33.11c). Horsetail stems are hollow, and their cells accumulate high levels of silica, earning them the name “scouring rush.” Today, horsetails are small plants, most less than a meter tall. However, tree-

In contrast, many ferns produce large leaves—

Despite the absence of secondary growth, some ferns can grow quite tall. Tree ferns, which can grow more than 10 m tall, produce thick roots near the base of each leaf that descend parallel to the stem to the ground. These roots increase the mechanical stability of the plant and also allow it to transport more water (Fig. 33.13a). Other ferns grow tall by producing leaves that twine around the stems of other plants, using the other plant for support. At the other extreme are tiny aquatic ferns such as Salvinia (see Fig. 33.11e) and Azolla (Fig. 33.13b) that float on the surface of the water.