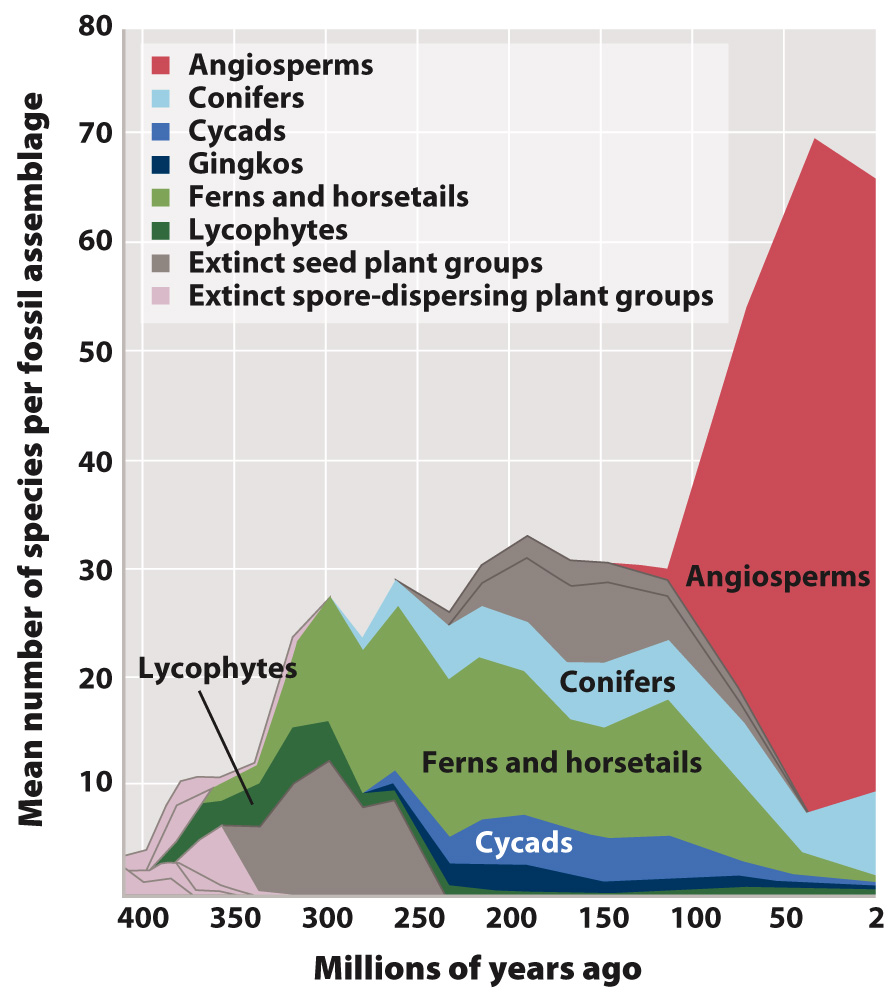

Plant diversity has changed over time.

If we tabulate the numbers of species within each major branch on the phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 33.1, one fact stands out: Of the nearly 400,000 species of plants present today, approximately 90% are angiosperms. Furthermore, angiosperms are relative newcomers (Fig. 33.2). They appeared in the fossil record about 140 million years ago. The oldest known evidence of land plants is found in rocks approximately 465 million years old. Thus, for more than 300 million years, terrestrial vegetation was made up of plants other than angiosperms. During this period, lycophytes, ferns and horsetails, and gymnosperms, as well as many groups of now-

Once the flowering plants gained an ecological foothold, however, the number of angiosperm species increased at an unprecedented rate. As the number of angiosperm species rose, the number of species in other groups fell. Yet the total number of plant species increased dramatically. Thus, angiosperms’ hold on plant diversity is the result of both squeezing out other groups and increasing the number of species that can coexist.

One way that angiosperm evolution may have increased the overall number of plant species on Earth was by transforming the environments into which they diversified. Climate models suggest that angiosperms may have been necessary for the formation of tropical rain forests as we know them today. Without the higher rates of transpiration exhibited by angiosperms, many tropical regions would have higher temperatures and lower rainfall. The warmer, drier conditions would have been less conducive to the luxuriant plant growth found in tropical rain forests. The new tropical forests, with their dense shade and humid understories, provided new habitats into which both angiosperms and non-