Fungi proliferate and disperse using spores.

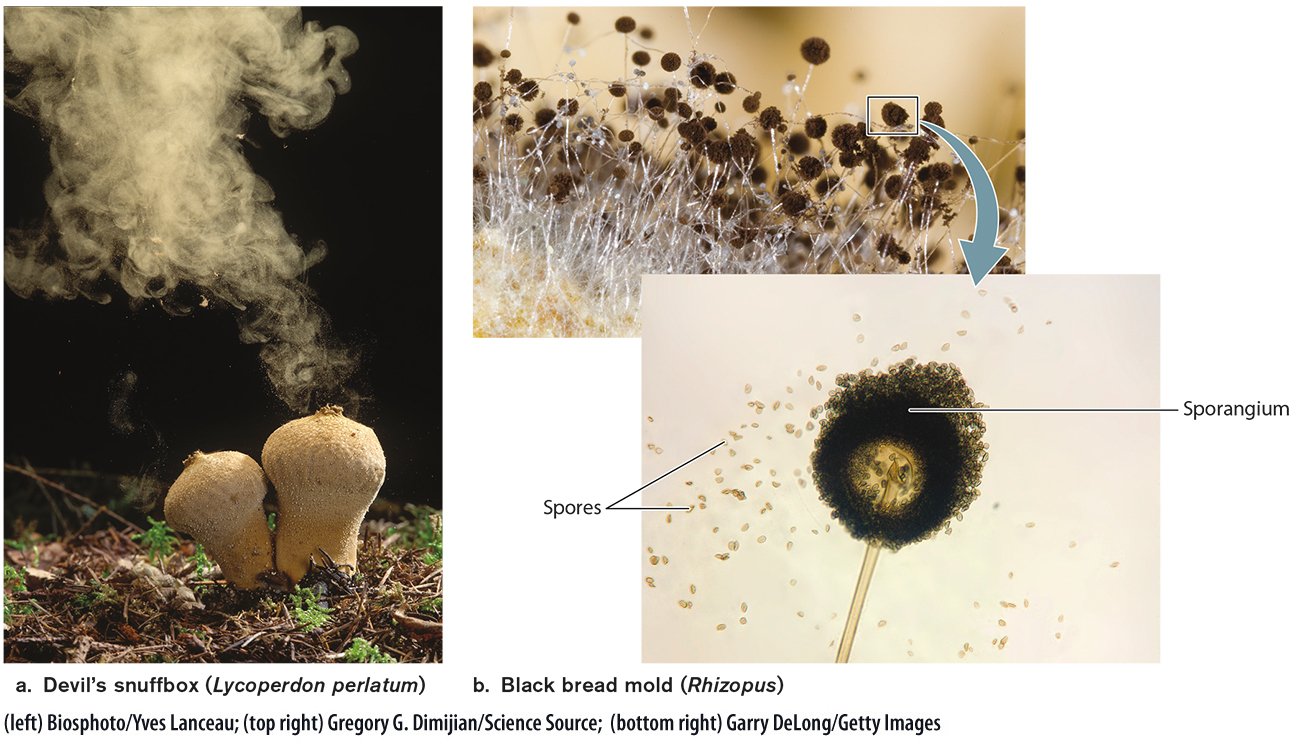

The tissues, living or dead, that support fungal growth often have a patchy distribution. For this reason, fungi must be able to disperse from one food source to another. The extensive networks of hyphae within soils or host organisms can spread locally but cannot disperse over great distances, so fungi produce spores that can be carried by the wind (Fig. 34.10a), in water, or attached to (or within) animals. In early-

The probability that any given spore will come to rest in a favorable habitat is low, so fungi produce large numbers of spores. Fungal spores remain viable, able to grow if provided with an appropriate environment, for periods ranging from only a few hours in some species to many years in others. Thus, spores allow fungi to use resources that are patchy in time as well as in space. In fact, a shortage of resources is one of the cues that triggers spore formation.

Spores can form by meiotic cell division as part of sexual reproduction, and they can also form asexually. Asexual spores are formed by mitotic cell division and therefore are genetically identical to their parent. In many species, asexual spores are produced within sporangia that form at the ends of erect hyphae, allowing the release of the spores into the air. A close look at a moldy piece of bread reveals that the surface is covered with hyphae carrying sporangia containing asexual spores (Fig. 34.10b).

Fungal species vary in the extent to which they rely on asexual as opposed to sexual spore production. In some groups, such as the group that includes the most common mushrooms, sexual reproduction is the dominant means of spore production. On the other hand, in a small number of fungi that includes the endomycorrhizal species, spores produced by meiotic cell division have never been observed. Although sexual reproduction appears to be absent in some fungal species, asexual fungi have other mechanisms for producing genetic diversity, as discussed later in this section.