Ascomycetes are the most diverse group of fungi.

Ascomycetes make up 64% of all known fungal species. They include important wood-

Ascomycetes include both species that form multicellular fruiting bodies and ones that form unicellular yeasts. A remarkable feature of ascomycete fruiting bodies is that they contain both dikaryotic and haploid cells. The proliferation of dikaryotic cells leads to the production of many asci, while the growth of haploid cells contributes to the bulk of the fruiting body. Two ascomycete lineages consist largely of yeasts. The earliest branching members in these groups, however, produce hyphae. Thus, the unicellular nature of yeasts is a derived feature evolved through loss of hyphae and is not an ancestral condition.

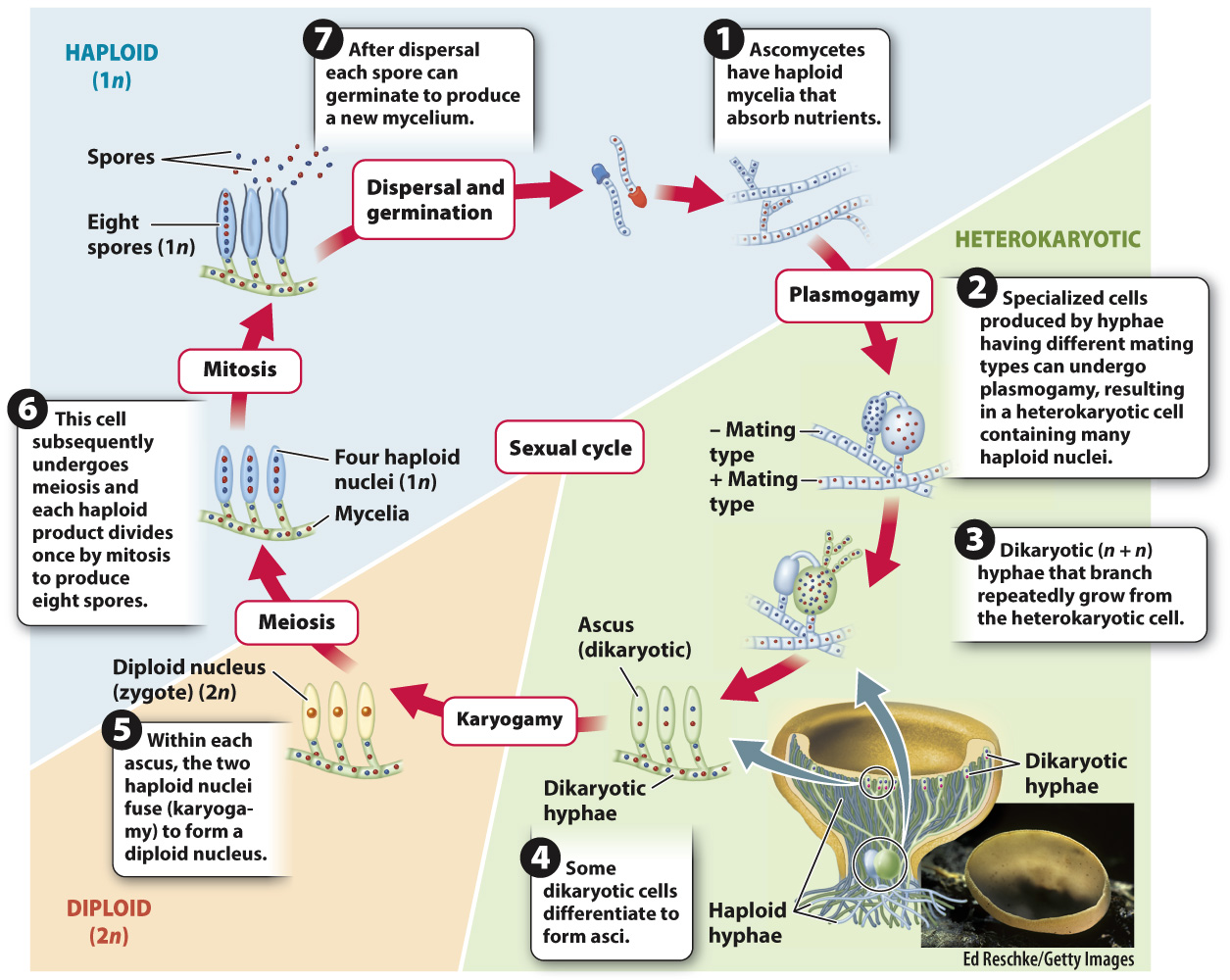

Fig. 34.19 illustrates the life cycle of a common ascomycete, the brown cup fungus. In ascomycetes, meiosis is followed by a single round of mitosis, resulting in asci that contain eight haploid spores. When mature, the spores are ejected from the top of the asci, expelled by turgor pressure. In many ascomycetes, fruiting bodies elevate the asci on one or more cup-

In the fruiting bodies of some ascomycetes, the asci are completely enclosed by a layer of tissue and thus must be dispersed by other organisms rather than by the wind. The truffles prized in cooking provide an example. The edible truffle is the fruiting body of an ascomycete that grows as an ectomycorrhizal fungus on tree roots. Not only do truffles encase their spores in protective tissues, but they also develop underground. How, then, can their spores be dispersed? Developing truffles release androstenol, a hormone also produced by boars before mating. The hormone attracts female pigs, which unearth and consume the fruiting body. The spores pass through the pig’s digestive tract without damage and are released into the environment in feces, thereby dispersing the spores.

Another ascomycete is thought to have played a role in the events that unfolded in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692. That year, several girls came down with an unknown illness manifested by delirium, hallucinations, convulsions, and a crawling sensation on the skin. The girls were thought to be bewitched, and subsequent accusations led to the infamous Salem witch trials. They were executed for witchcraft, but today many scholars prefer a simpler diagnosis for the illness: poisoning by the ascomycete fungus ergot. Ergot is a common pathogen of rye and related grasses, and ingestion of contaminated plants can lead to the symptoms reported in Salem. Like many defensive compounds produced by plants, alkaloid molecules produced by ergot and their derivatives are used in medicine in low doses, such as in the treatment of migraines.

Ascomycetes are even known for producing so-

HOW DO WE KNOW?

FIG. 34.20

Can a fungus influence the behavior of an ant?

BACKGROUND A curious death ritual unfolds in the rain forest of Thailand. Spores of the ascomycete fungus Ophiocordyceps infect Camponotus leonardi ants, growing hyphae inside their bodies. The fungus eventually kills the ant, and fruiting bodies emerge from the dead ant’s head to disperse spores that begin the life cycle anew. Camponotus leonardi nests and forages for food high in the forest canopy. Infected ants, however, undergo convulsions that cause them to fall to the forest floor. The infected ants wander erratically and are unable to climb more than a few meters above the ground before convulsions make them fall again. In their final act, the ants bite into the undersides of leaves and die. The fungus is then able to complete its life cycle within the humid forest understory. Is the ants’ behavior, including both the convulsions and leaf biting, induced by the fungi?

HYPOTHESIS Parasitic fungi manipulate ant behavior to complete their own reproductive cycle.

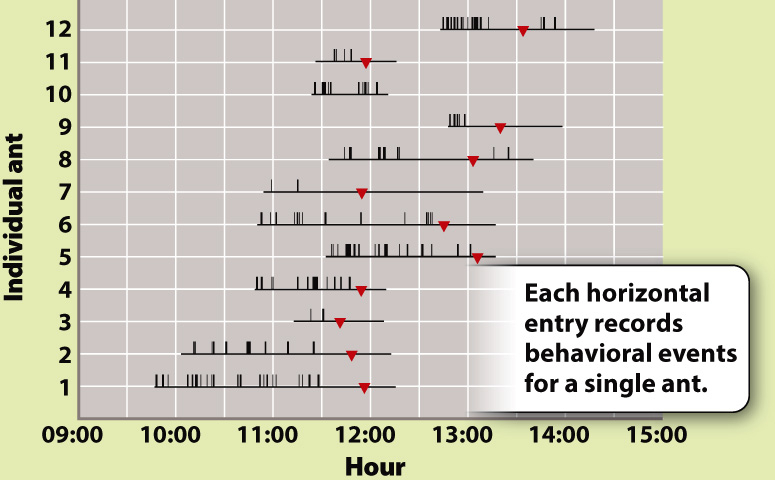

OBSERVATIONS Infected and uninfected ants were observed for many hours and behavioral events were recorded.

RESULTS Infected ants have repeated convulsions (indicated by vertical bars in the graph), but uninfected ants show no such behavior (not shown). Transitions from erratic wandering to a “death grip,” in which the ant bites into a leaf (indicated by red triangles in the graph and shown in the photograph), occurred at about the same time of day. Dissections showed that the ants’ death grip results from jaw-

CONCLUSION The fungi change the behavior of infected ants, inducing a stereotypical behavior that facilitates completion of the fungus’s life cycle. The molecular basis of this manipulation is not yet known.

FOLLOW-

SOURCE Hughes, D. P., et al. 2011. “Behavioral Mechanisms and Morphological Symptoms of Zombie Ants Dying from Fungal Infections.” BMC Ecology 11:13–