Basidiomycetes include smuts, rusts, and mushrooms.

The basidiomycetes, which make up 34% of all described fungal species, include three major groups (Fig. 34.21). Two of these—

Rusts can also have profound impacts on plant function and development. For example, the rust Puccinia monoica alters leaf development in its host plant Arabis, resulting in a pseudoflower that attracts insects by visual and olfactory cues as well as nectar rewards. These pseudopollinators transport spores, thus enhancing outcrossing as well as dispersal of the fungi, but provide no service to the plant. We discuss the biology of rusts in greater detail in the next section when we examine Ug99, a highly virulent wheat rust first reported in Uganda in 1999.

The third basidiomycete group is characterized by the formation of multicellular fruiting bodies, including the iconic toadstools with their central stalk and umbrella-

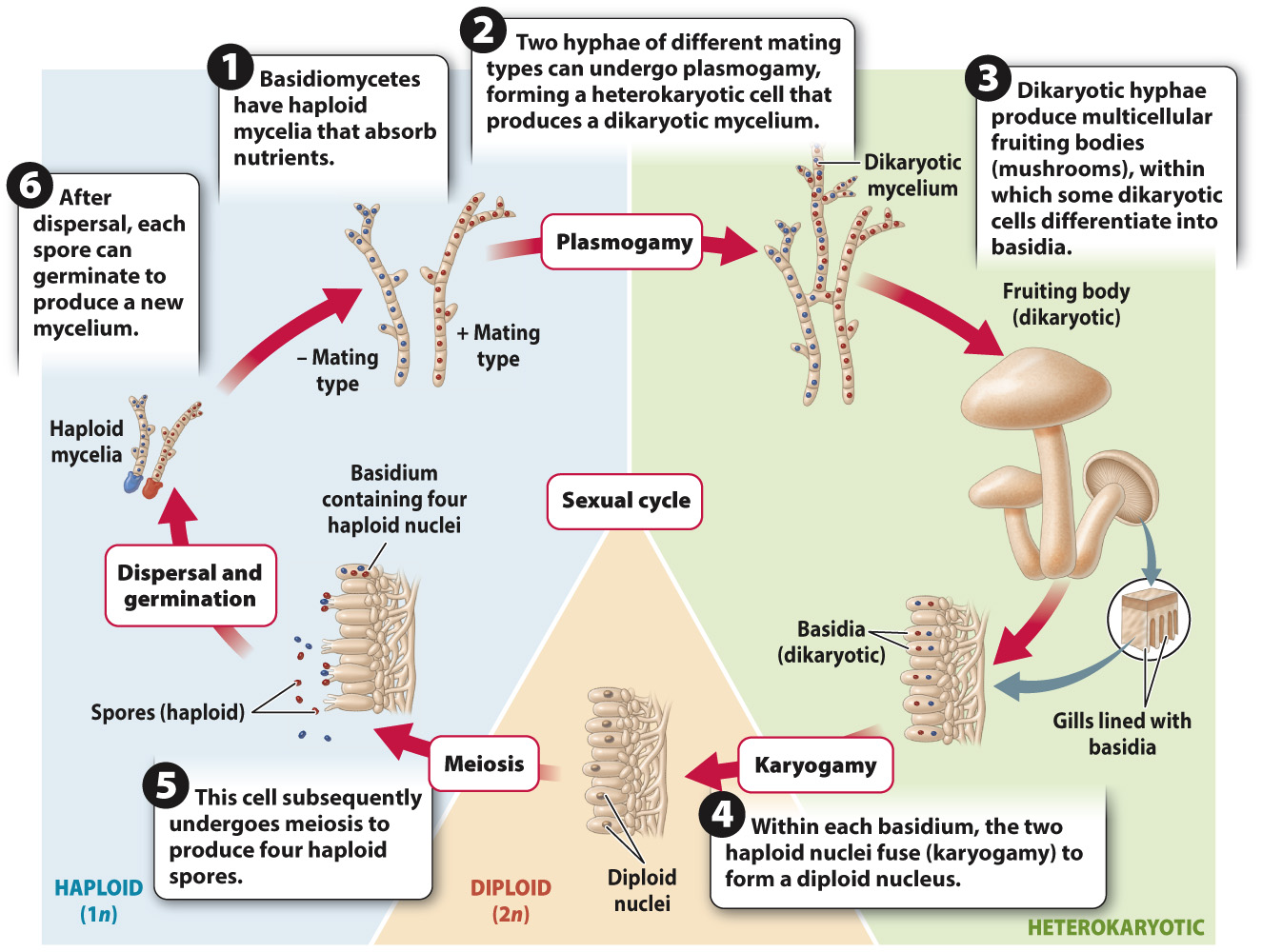

Fig. 34.23 shows the life cycle of a typical basidiomycete mushroom. The life cycle is similar to that of ascomycetes (see Fig. 34.19), except that the fruiting body is made up entirely of dikaryotic hyphae instead of a combination of dikaryotic and haploid hyphae as in ascomycetes. In addition, nuclear fusion (karyogamy) takes place in a specialized cell called a basidium rather than in an ascus. Finally, the haploid products of meiosis (the spores) do not undergo mitosis, so four spores are produced from each basidium rather than eight spores from each ascus.

Quick Check 4 When you eat a mushroom, what stage of its life cycle are you consuming?

Quick Check 4 Answer

You are eating the multicellular fruiting body built from dikaryotic hyphae.

Most species in this group live by forming ectomycorrhizal associations or by decomposing wood and other substrates. The fruiting bodies that we see elevated above a rotting log or the soil are connected to extensive mycelia that provide resources for fruiting-

Elevation alone does not ensure dispersal because the spores must penetrate a boundary layer of air that surrounds the fruiting body. Many basidiomycetes depend on surface tension to catapult their spores through the air. The placement of their four spores on the ends of short stalks is the key to this mechanism. Both the spores and the supporting basidial cell actively secrete solutes that cause water to condense on their surfaces. At first, the droplets are independent, but as they grow they eventually come into contact with one another, and at this point the high surface tension of water causes them to merge into a single, smooth droplet. This change in shape shifts the center of mass of the water with such force that it catapults the spore into the air.

Basidiomycetes that form conspicuous fruiting bodies have diverse mechanisms for dispersing their spores. For example, puffballs function like bellows: The impact of raindrops forces the loose, dry spores out of a small hole at the tip of the ball (see Fig. 34.10a). Bird’s nest fungi function like splash cups: In this case, raindrops displace groups of spores (the “eggs” in the nest) onto nearby vegetation. Herbivores consume the spores when they feed on the vegetation and transport them to a new dung pile. Stinkhorns produce spores in a stinky, sticky mass that attracts insects, which then carry off spores that stick to their legs and body.