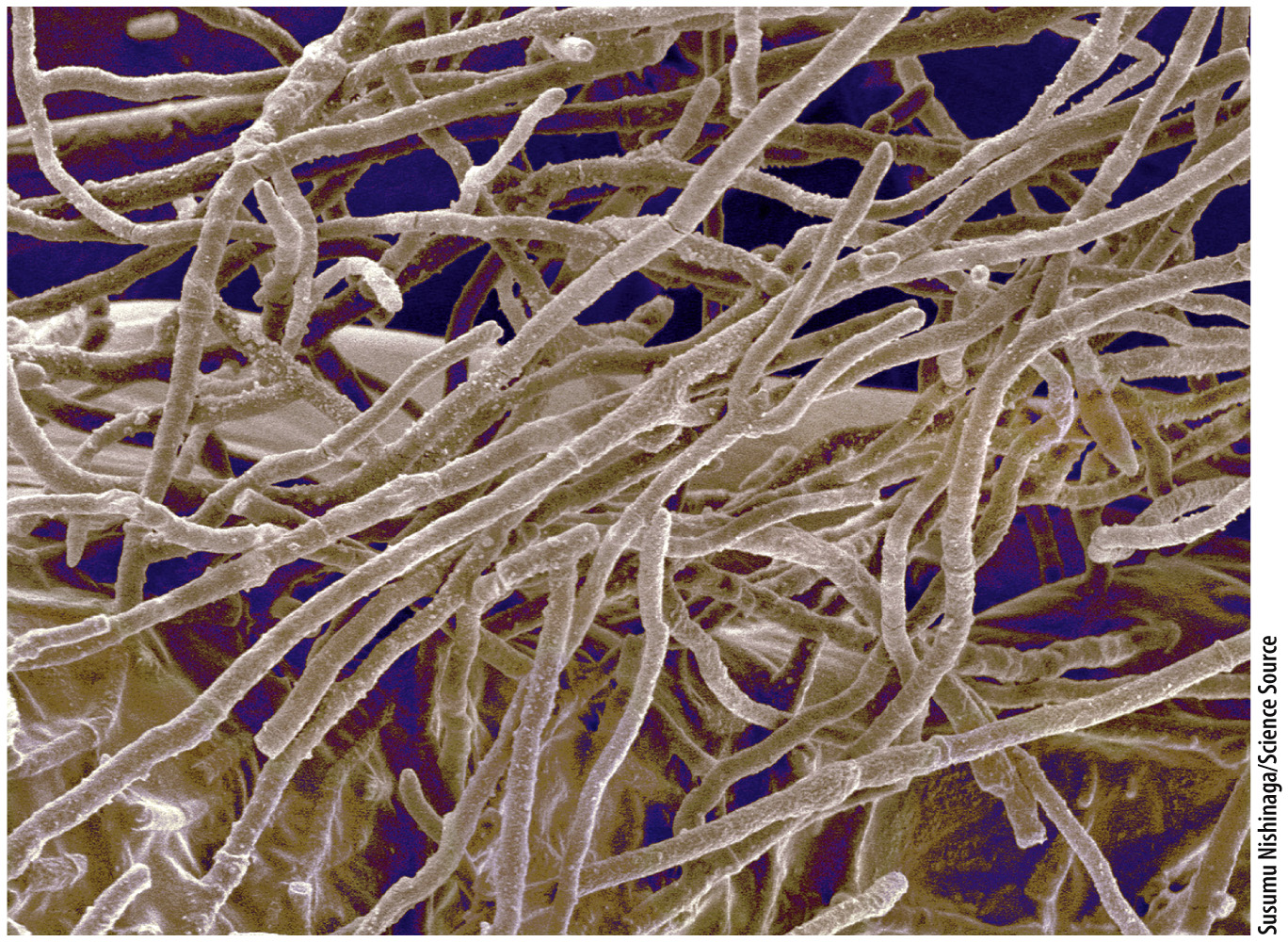

Hyphae permit fungi to explore their environment for food resources.

Most fungi consist of highly branched, multicellular filaments called hyphae (Fig. 34.1). The hyphae are slender, typically 10 to 50 times thinner than a human hair. The numerous long, thin hyphae provide fungi with a large surface area for absorbing nutrients.

Hyphae maintain their slender form by growing only at their tips. Elongating hyphae thus penetrate ever farther into their environment, encountering new food resources as they grow. Where resources are low, growth is slow or may stop entirely. On the other hand, when fungi encounter a rich food resource, they grow rapidly and branch repeatedly, forming a network of branching hyphae called a mycelium (plural, mycelia). Mycelia can grow to be quite large—

A strong but flexible cell wall is key to hyphal growth and nutrient transport. In fungi, cell walls are made of chitin, the same compound found in the exoskeletons of insects. Chitin is a modified polysaccharide that contains nitrogen. Because of their chemical makeup, fungal cell walls are thinner than plant cell walls. Fungal cell walls prevent hyphae from swelling as water flows into the cytoplasm by osmosis. Thus, the wall prevents cells from rupturing when exposed to dilute solutions such as those in freshwater environments and in the soil. Moreover, the inflow of water by osmosis provides the force that enables fungi to explore their surroundings: the inflow of water generates positive turgor pressure (Chapters 5 and 29), pushing the hyphal tip ever deeper into the local environment.