Antagonist pairs of muscles produce reciprocal motions at a joint.

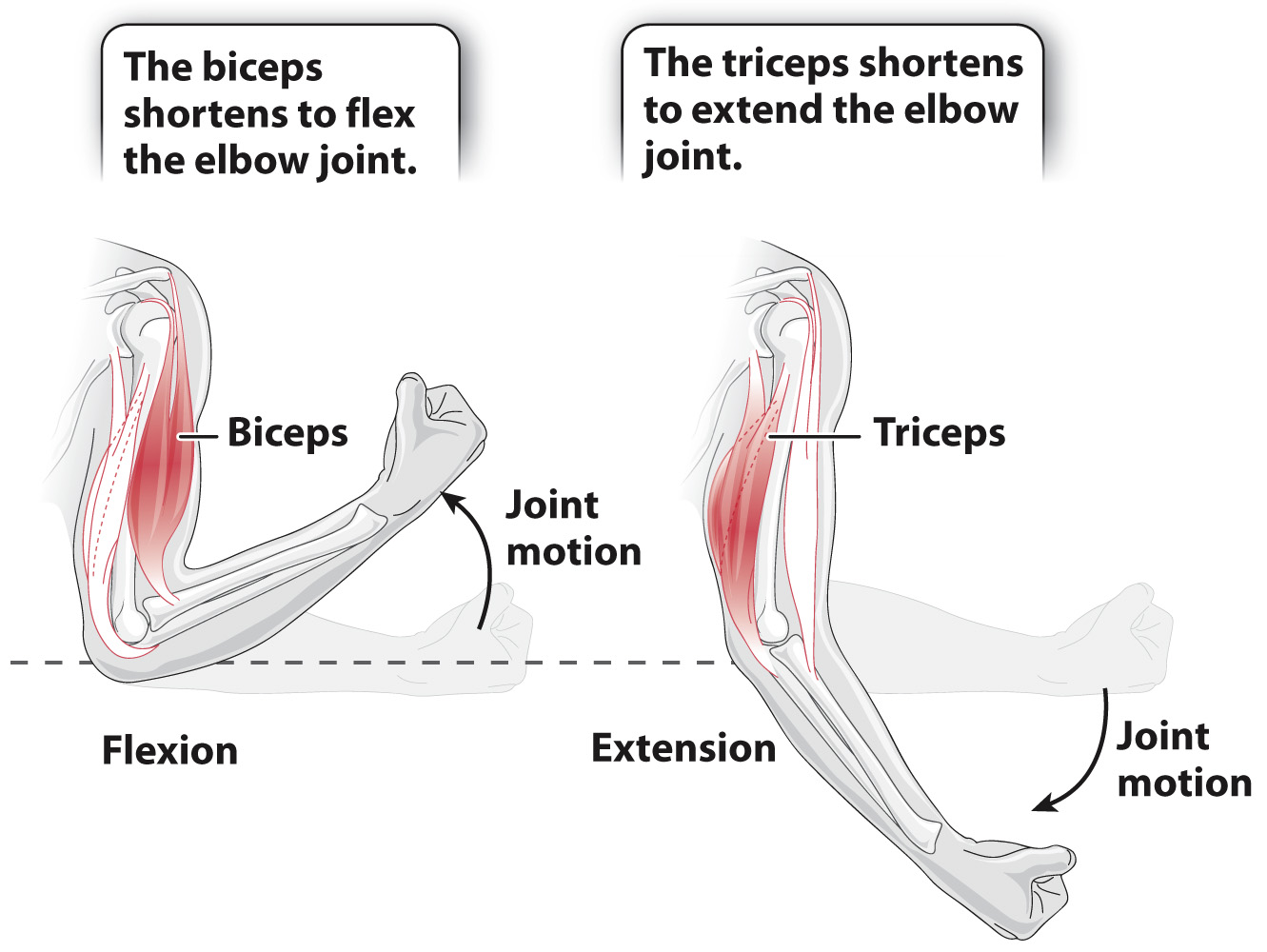

Muscles can generate force only by pulling, not pushing, on the skeleton. Therefore, to produce reciprocal joint and limb movements, they are arranged as pairs of antagonist muscles that pull in opposite directions. Flexion is the joint motion that moves bone segments closer together, and extension is the joint motion that moves them farther apart. For example, muscles at the elbow joint are organized as flexors (the biceps muscle) that contract to bring the arm toward the shoulder, and extensors (the triceps muscle) that contract to extend the arm away from the shoulder (Fig. 37.11). Additional pairs of antagonist muscles are present for movements in other directions. Muscles in the body wall of cnidarians (jellyfish and sea anemones) and segmented annelid worms, as well as the smooth muscles in the walls of intestines, are organized in longitudinal (lengthwise) and circumferential (circular) layers, allowing them to function as muscle antagonists that control movement and shape.

In contrast, when muscles combine to produce similar motions, they are termed muscle agonists. Muscles arranged as agonists increase the strength and improve the control of joint motion. For example, the three heads of the triceps are agonists of each other (Fig. 37.11).