Hydrostatic skeletons support animals by muscles that act on a fluid-filled cavity.

Hydrostatic skeletons evolved early in multicellular animals with the first cnidarians (jellyfish and anemones) approximately 600 million years ago. They are found in nearly all multicellular animals as well as in many vascular plants. In animals that depend on a hydrostatic skeleton, fluid contained within a body cavity serves as the supportive component of the skeleton. Muscles exert pressure against the fluid to produce movement.

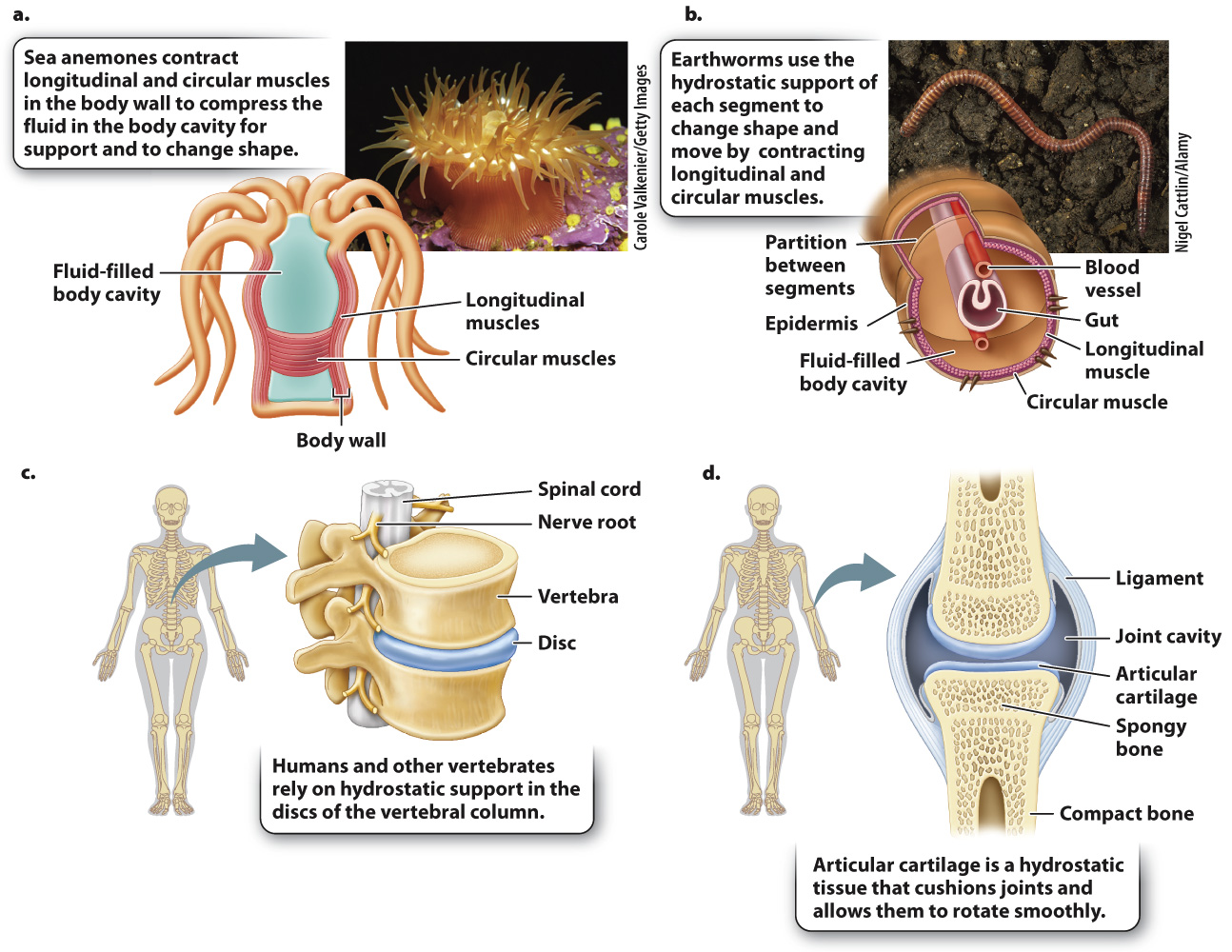

Two sets of opposing muscles surround the fluid, controlling the width and length of the body cavity and, in many cases, of the whole animal (Fig. 37.15a). Circular muscles reduce the diameter of the body cavity, and longitudinal muscles reduce its length. A sea anemone can bend its body in various directions to feed or to resist water currents by closing its mouth to keep its fluid volume constant and contracting its circular and longitudinal muscles. Sea anemones extend themselves into the water column by contracting their circular muscles and relaxing their longitudinal muscles. Controlling the amount of fluid in their body cavity also allows sea anemones to adjust their shape. When threatened, a sea anemone rapidly retracts by contracting its longitudinal muscles and allowing water to escape from its body cavity.

Similarly, earthworms burrow through the soil by moving a series of hydrostatic segments along their body (Fig. 37.15b). By contracting longitudinal muscles in a few segments, they shorten those segments and also widen them to anchor those segments against the soil. They then extend intervening segments between anchor points by contracting circular muscles, causing the segments to lengthen and move the animal’s body through the soil.

Because of their simple but effective organization, hydrostatic skeletons are well adapted for many uses. In animals such as squid and jellyfish, the hydrostatic skeleton has become specialized for jet-

Even vertebrate animals with rigid endoskeletons have hydrostatic elements that provide flexibility and cushion loads transmitted by the skeleton. These include intervertebral discs and cartilage. Intervertebral discs are sandwiched between the bony vertebrae of the backbone (Fig. 37.15c). Each disc has a wall reinforced with connective tissue that surrounds a jelly-