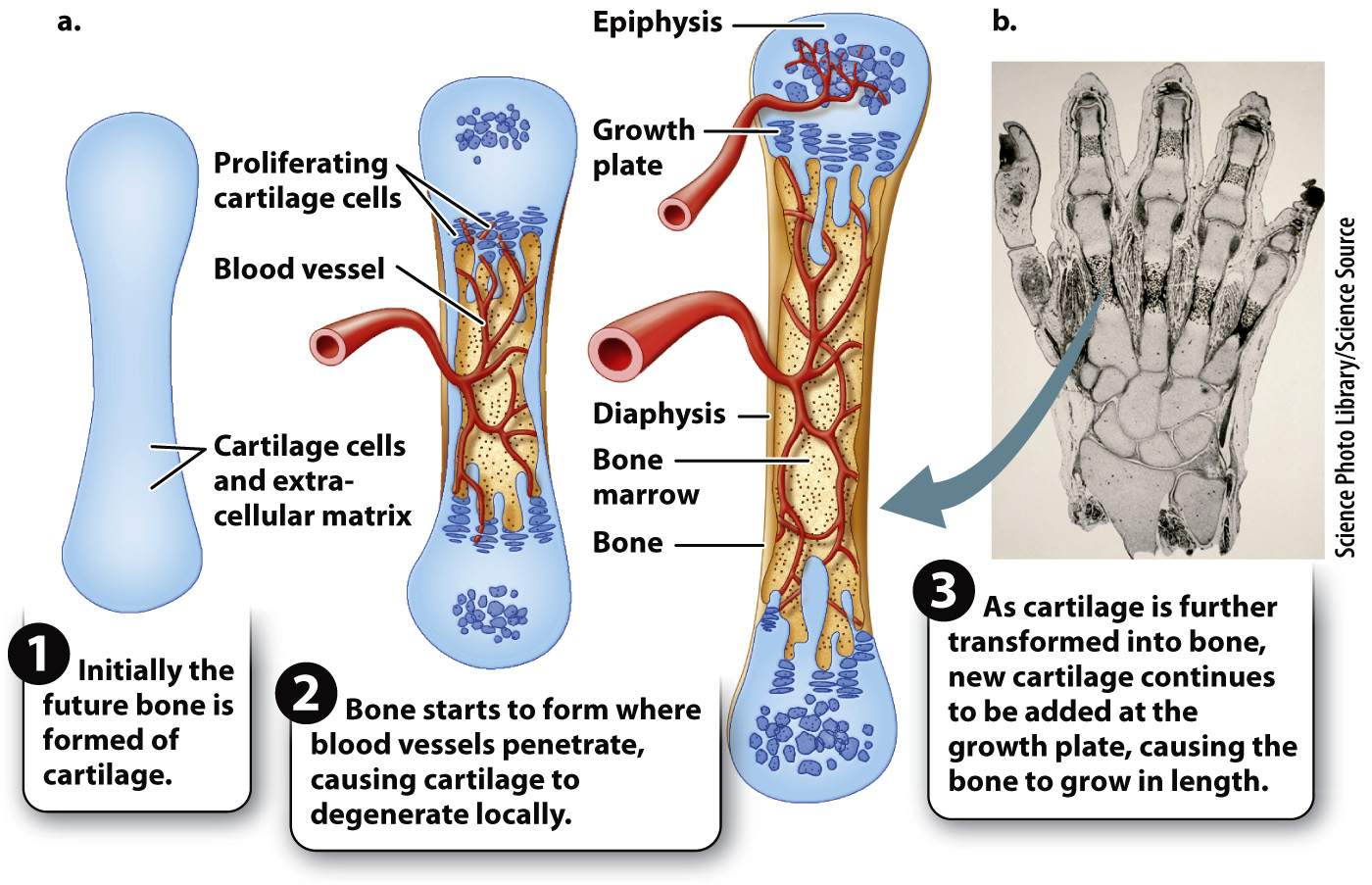

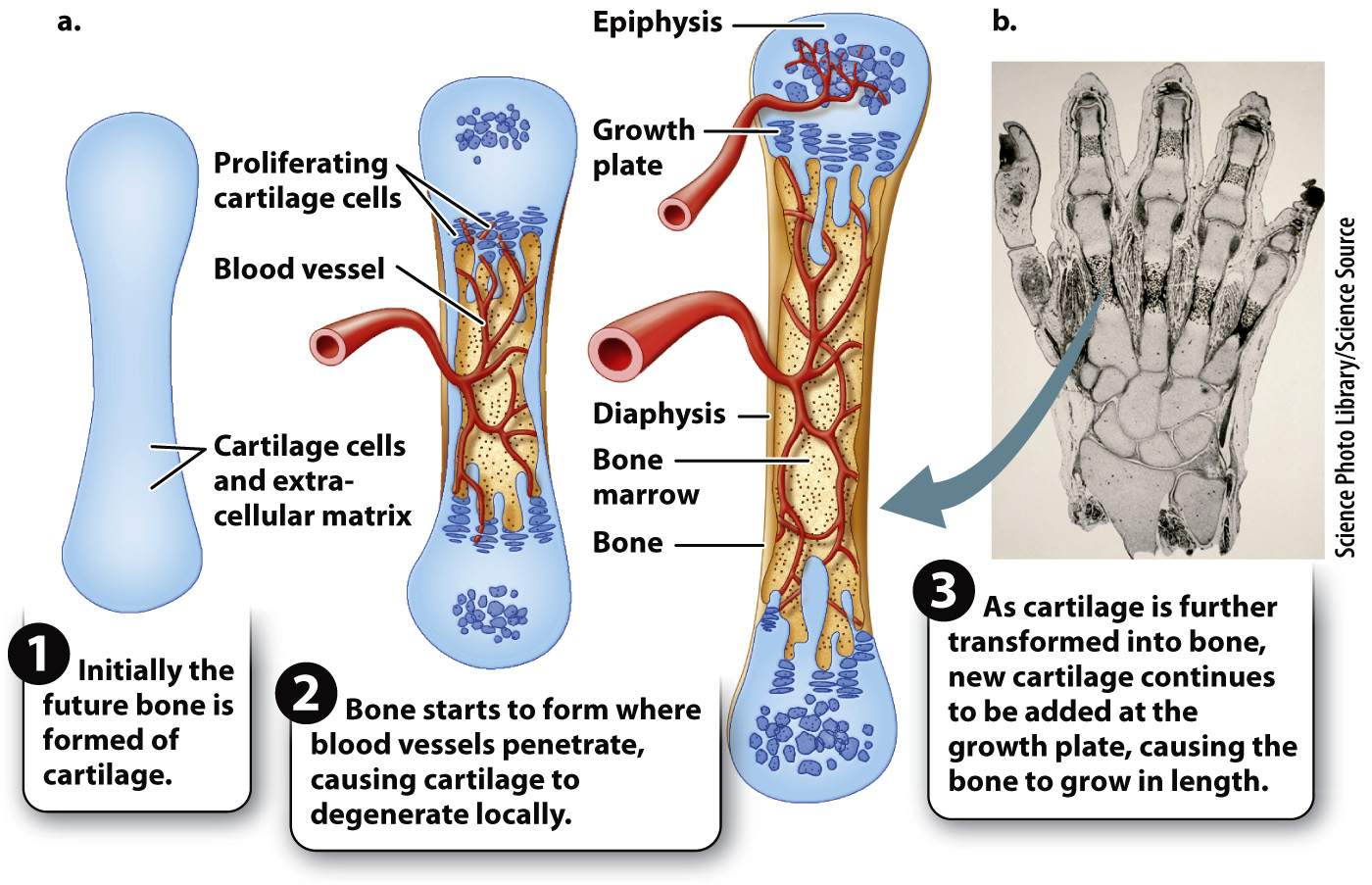

This method of forming bone is slow, however, and, if most bones in the body formed this way, the fetus would take a very long time to develop. Most other bones of the body—the vertebrae, shoulder, pelvis, and limb bones—are formed as cartilage first (Fig. 37.18). The precursor cells initially become cartilage-producing cells, known as chondroblasts, which in the embryo grow into cartilage models of most bones of the developing body (Fig. 37.18a). For example, at approximately 9 weeks of development, a human fetal hand consists mainly of this cartilage model (Fig. 37.18b). This embryonic cartilage is the same as the articular cartilage that remains at the ends of bones to form the joint surfaces. Because cartilage is a pliable, fluid-filled matrix, it grows by expansion within the structure as well as at the surface, enabling the fetal skeleton to grow rapidly. As the fetus grows and its skeleton matures, the cartilage model of the bone is invaded by blood vessels. The presence of blood vessels triggers the transformation of cartilage into hard, mineralized bone.

FIG. 37.18 Bone formation from a cartilage model. (a) Most bones other than the skull are formed as a cartilage first, followed by vascularization and the transformation into bone tissue by osteoblasts. (b) Cartilage model of a human fetal hand, showing initial sites of bone tissue formation at about 9 weeks of embryonic development.