The digestive tract has regional specializations.

In extracellular digestion, food is broken down in a specialized cavity or body compartment. Some animals, like sea anemones, carry out digestion in an internal cavity. Food flows directly into this cavity through the mouth. Cells lining the cavity secrete digestive enzymes that break down the food. These very same cells then absorb the smaller chemical compounds that are produced.

Other animals have evolved more elaborate digestive systems that allow the transport of food by a digestive tube that runs from an animal’s mouth to its anus. Collectively, the passages that connect the mouth, digestive organs, and anus constitute an animal’s gut or digestive tract. Because the food is moved in a single direction through a tubelike gut, particular regions of the digestive tract are specialized for different functions. These functions include the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food, absorption of released nutrients, and storage and elimination of waste products.

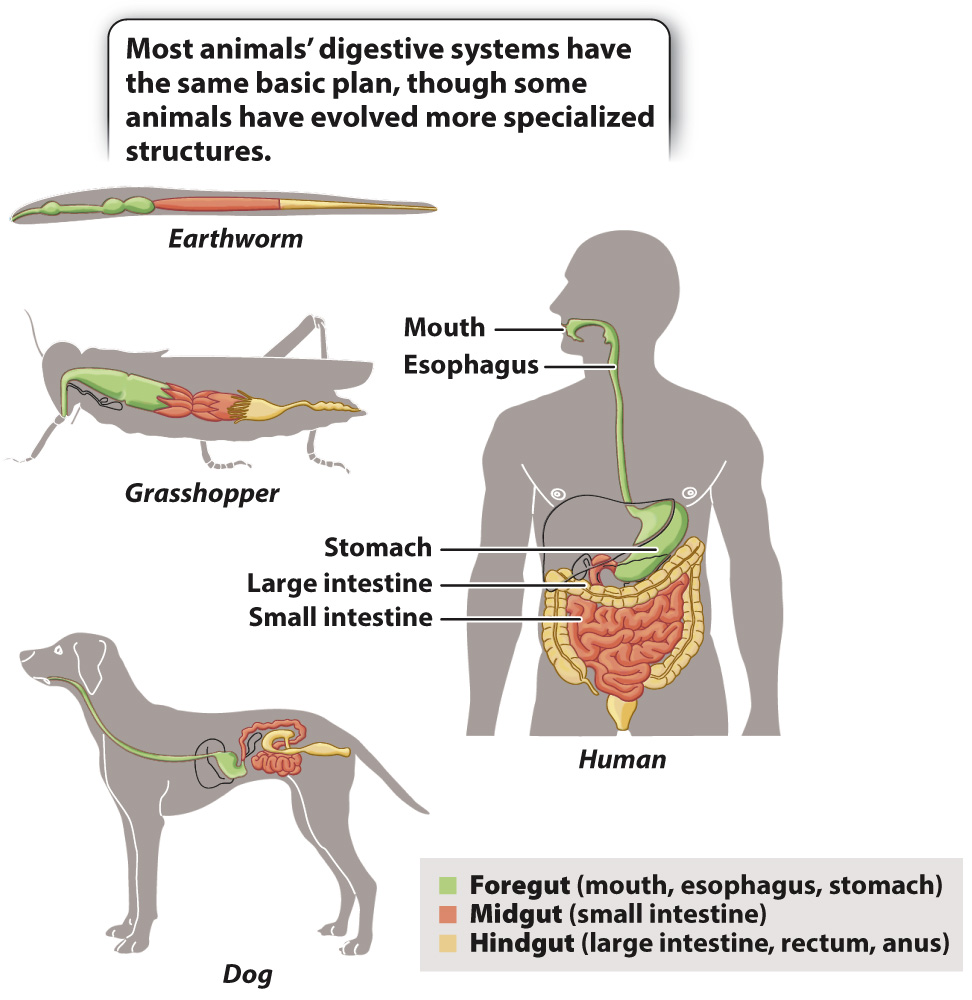

These various functions take place in the three main parts of the digestive tract: the foregut, midgut, and hindgut (Fig. 40.12). Most animals’ digestive systems have the same basic plan, though some animals have also evolved specialized structures. The foregut includes the mouth, esophagus, and stomach or crop, which serves as an initial storage and digestive chamber. Next is the midgut, which includes the small intestine, where the remainder of digestion and most nutrient absorption takes place. Here, specialized organs secrete enzymes and other chemicals that aid in the breakdown of particular macromolecules, such as fats and carbohydrates. Finally, the digested material reaches the hindgut, which includes the large intestine and rectum. In the hindgut, water and inorganic molecules are absorbed, leaving the waste products, or feces, which are stored in the rectum until being eliminated from the body.

Food and its breakdown products move through the gastrointestinal tract by peristalsis, waves of smooth muscle contraction and relaxation. These waves keep substances moving from one end of the tract to the other, and help to prevent backward movement.