The kidneys help regulate blood pressure and blood volume.

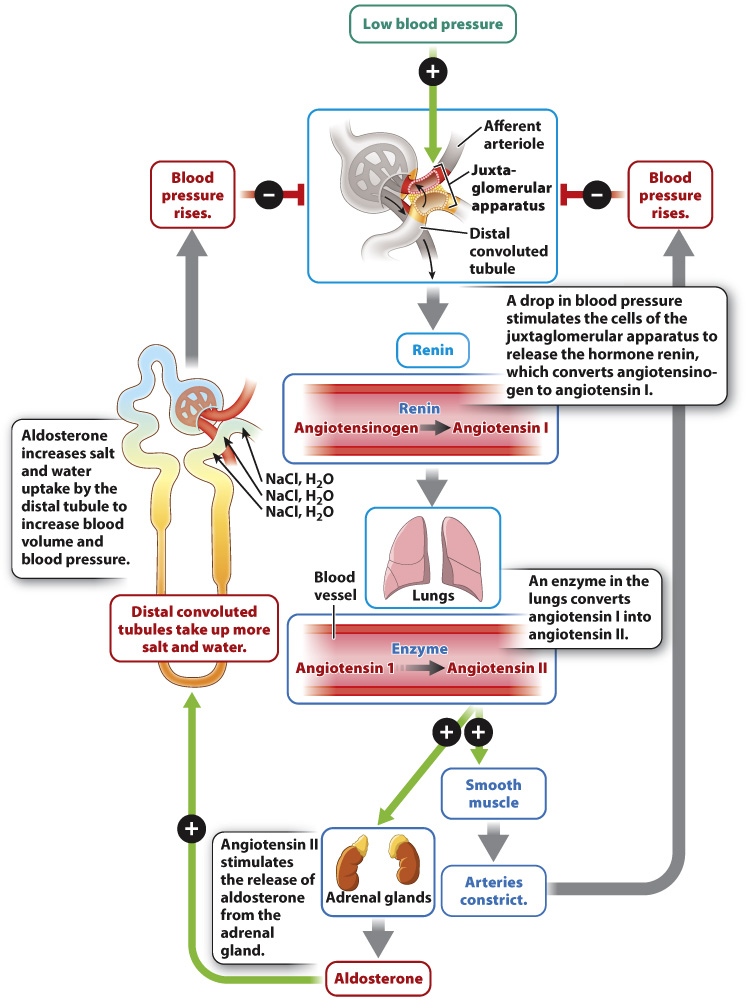

Because the kidneys receive a large fraction of the blood leaving the heart, they are well suited for monitoring changes in blood pressure and maintaining it at relatively constant levels, another example of homeostasis. Specialized cells of the efferent arteriole leaving the glomerulus of each nephron form the juxtaglomerular apparatus (Fig. 41.22). In response to a drop in blood pressure, these cells secrete the hormone renin. Renin converts angiotensinogen, which is produced in the liver and circulates in the blood, into angiotensin I. Angiotensin I in turn is converted by an enzyme present in the lungs and elsewhere to its active form, angiotensin II. Angiotensin II acts on the smooth muscles of arterioles throughout the body, causing them to constrict, thus increasing blood pressure and directing more blood back to the heart.

Angiotensin II also stimulates the release of the hormone aldosterone from the adrenal glands (Fig. 41.22). Aldosterone stimulates the distal convoluted tubule and collecting ducts to increase the reabsorption of electrolytes and water back into the blood. Blood volume increases and therefore blood pressure increases, too. The kidneys, therefore, play many roles. In addition to eliminating wastes and other toxic compounds, they maintain homeostasis in several ways, including through the maintenance of water and electrolyte balance and the regulation of blood volume and blood pressure.