Many species reproduce both sexually and asexually.

Most organisms that reproduce asexually are also capable of reproducing sexually. For example, hydras reproduce asexually by budding, but their ability to reproduce asexually does not preclude their ability to reproduce sexually. Even budding yeast are capable of sexual reproduction. Most aphids, fish, and reptiles capable of parthenogenesis can also reproduce sexually.

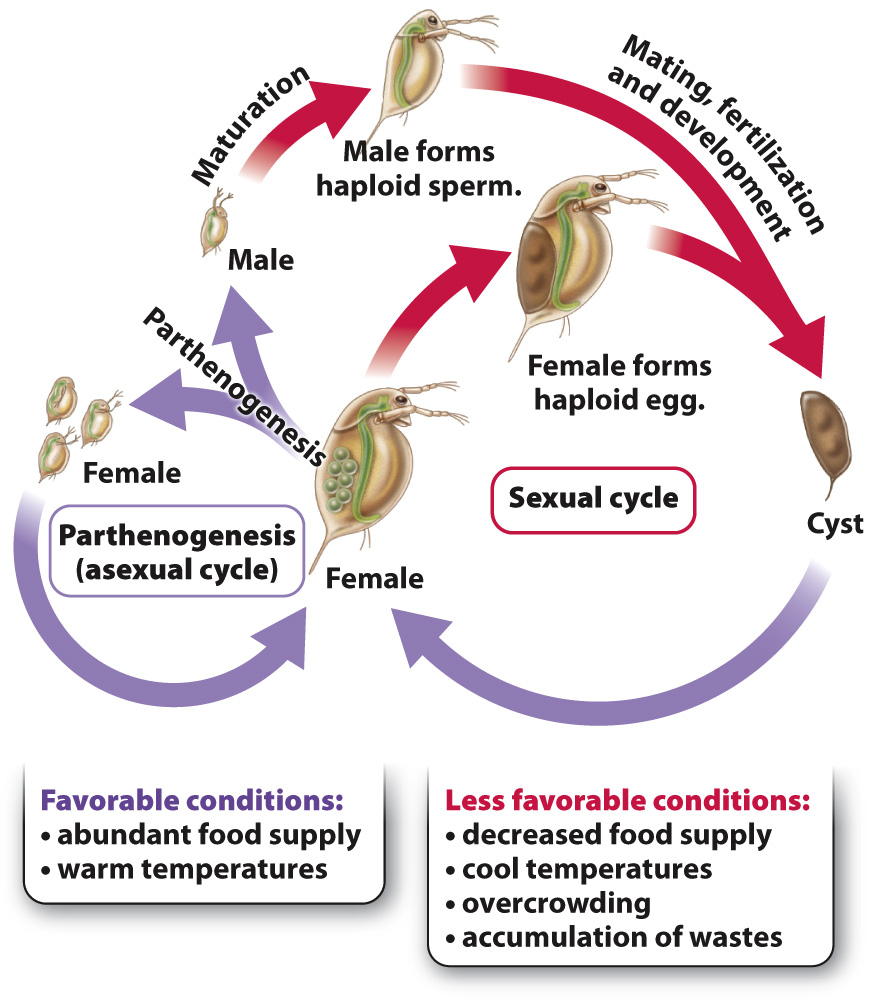

What determines when an organism reproduces sexually and when it reproduces asexually? This question has been examined in the freshwater crustacean Daphnia. Daphnia reproduces asexually by parthenogenesis in the spring, when food is plentiful, perhaps because asexual reproduction is a rapid form of reproduction that allows the organism to take advantage of abundant resources (Fig. 42.3). Later in the season, when conditions are less favorable because of increased crowding and decreased food and temperature, Daphnia reproduces sexually, mating to produce a zygote that starts to form an embryo. At an early stage, however, development is arrested and metabolism slows dramatically. The embryo forms a thick-

This link between environmental conditions and mode of reproduction has been observed in many other species, from algae to slime molds. The life cycle of Daphnia hints that asexual reproduction and sexual reproduction have costs and benefits, a subject we turn to now.