43.3 Adaptive Immunity: B Cells and Antibodies

The innate immune system can react to diverse pathogens and has the capacity to distinguish self from nonself. The adaptive immune system shares these features, and has two additional features not present in the innate immune system. The first is specificity: The adaptive immune system produces an array of molecules, each of which has the potential to target a specific pathogen it has never before encountered. As a result, it is often more effective at eliminating a pathogen than the innate immune system. The second is memory: The adaptive immune system remembers past infections and mounts a stronger response on re-

Consider for a moment the number of pathogens that we might encounter—

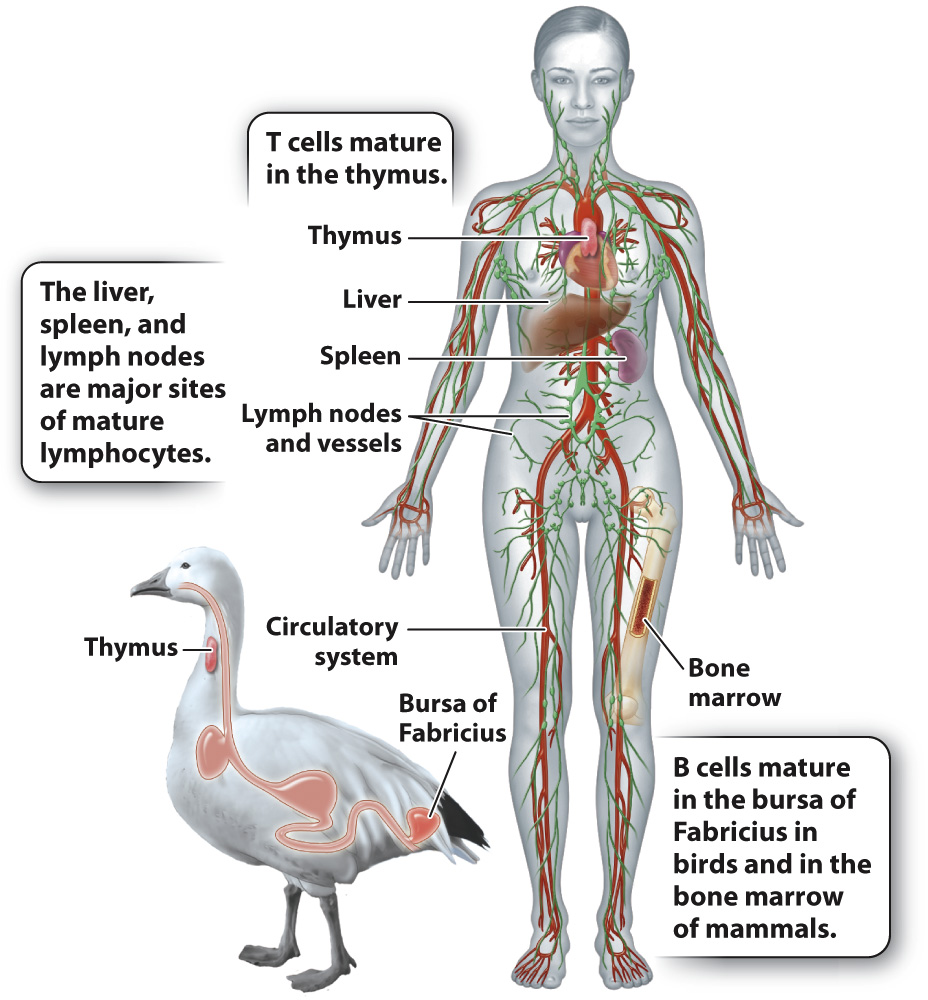

While many cells and tissues play a role in adaptive immunity, two white blood cell types are particularly important: B lymphocytes or B cells, and T lymphocytes or T cells (see Fig. 43.3). B and T cells are named for their sites of maturation. In birds, B cells mature in the bursa of Fabricius, an organ located off the digestive tract (Fig. 43.8). In mammals, B cells mature in the bone marrow. In most vertebrates, T cells mature in the thymus, an organ of the immune system located just behind the sternum, or breastbone. B and T cells circulate in blood vessels and lymphatic vessels, which are thin-