The common ancestor of tetrapods had four limbs.

Most animal phyla occur in the oceans, and many are exclusively marine. A subset of animal phyla has successfully colonized fresh water, and a smaller subset has radiated onto the land. Eleven groups on the animal phylogenetic tree contain both aquatic and terrestrial species: nematodes, flatworms, annelids (earthworms and leeches), snails, tardigrades (microscopic animals with eight legs, sometimes called water bears), onychophorans (velvet worms), four groups of arthropods (millipedes and centipedes, scorpions and spiders, land crabs, and insects), and vertebrates. In each of these groups, the aquatic species occupy the earliest branches, and the terrestrial species occupy later branches. No two of these groups share a last common ancestor that lived on land; thus, they all made the transition independently. Earlier, we outlined the extraordinary diversity of terrestrial arthropods. Here, we focus on vertebrates as the other great animal colonists of the land.

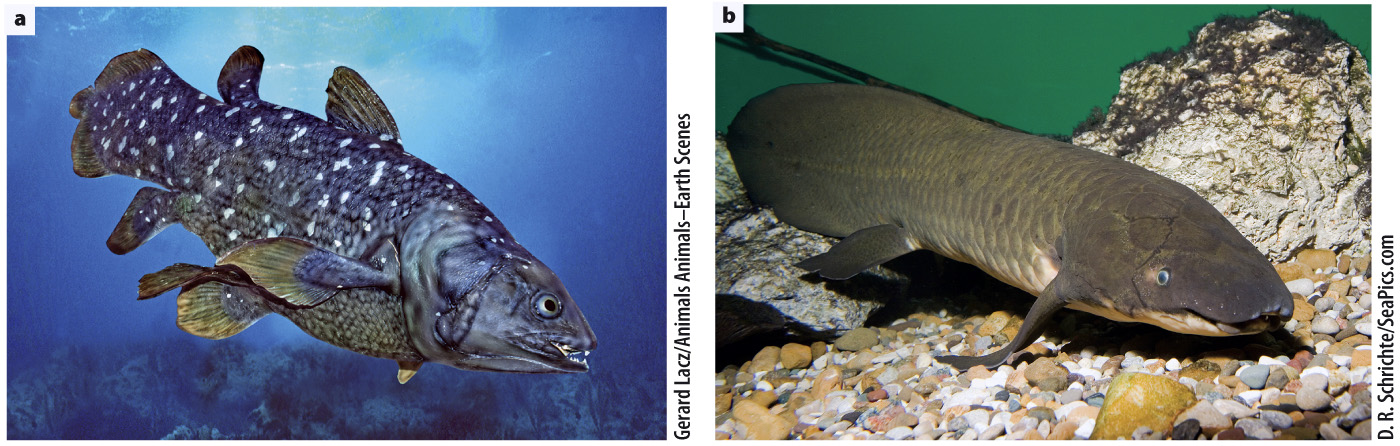

Most bony fish have fins supported by a raylike array of thin bones. About half a dozen closely related species, however, have pectoral and pelvic fins that extend from a muscularized bony stalk. These fish are called lobe-

Fossils document the anatomical transition in vertebrate animals as they moved from water to land, showing changes in the form of the limbs, rib cage, and skull (see Fig. 23.20). Living tetrapods include amphibians, such as frogs and salamanders; lizards, turtles, crocodilians, and birds; and mammals. The last common ancestor of all these animals had four limbs, hence the name Tetrapoda (“four legs”). Some, however, like snakes and a few amphibians and lizards, have lost their legs in the course of evolution.

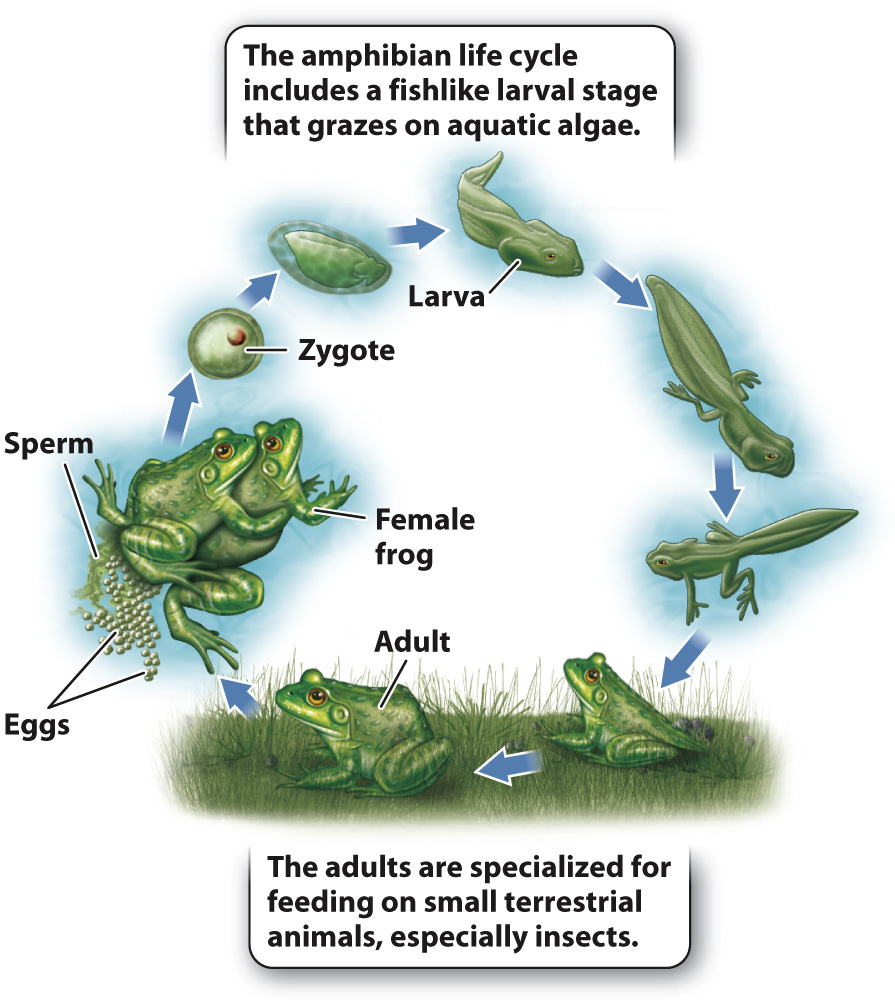

There are over 4500 species of Amphibia (“double life”), ranging in size from tiny frogs a few millimeters in length to the Chinese Giant Salamander, which is over 1 m long. Their name reflects their distinctive life cycle (Fig. 44.36). Most species have an aquatic larval form with gills that permit breathing under water and a terrestrial adult form that usually has lungs for breathing air. Amphibians must reproduce in the water or moist habitats, and so are not completely terrestrial. Whereas many amphibian larvae graze on algae, the adults are predators and often have a muscular tongue for capturing prey. Many are protected by toxins they secrete from glands in their skin, sometimes advertised by their brilliant color patterns. Most amphibian adults require moist skin for breathing and consequently have small lungs, with toads and red efts being notable exceptions. This is why frogs in particular have fallen victim to a fungus that affects the skin’s ability to breathe (Chapter 49).