45.1 Tinbergen’s Questions

We begin our exploration of animal behavior by asking a simple question: Why does an animal exhibit a particular behavior? The Dutch behavioral biologist Niko Tinbergen divided this overarching question into four separate questions, each one focusing on a different aspect of the behavior. Let’s consider an example: Why does a bird sing? While apparently straightforward, this question can be broken down into more specific questions and then answered in a number of different ways:

Causation. What physiological mechanisms cause the behavior? This question can have multiple answers. A bird sings because its hormone levels have changed in response to changes in day length. Or, more immediately, a bird sings because air passing through its specialized singing organ, the syrinx, causes membranes to vibrate rhythmically.

Development. How did the behavior develop? Here, the focus is on the role of genes and the environment in shaping the development of the behavior. In birds, typically it’s the male that sings, and he has learned the song from his father or other males.

Adaptive function. How does the behavior promote the individual’s ability to survive and reproduce? In this case, the answer to the question might be that a male bird sings in order to attract a mate and then reproduce.

Evolutionary history. How did the behavior evolve over time? Complex bird songs may have evolved from vocalizations made by ancestors that became increasingly standardized over time, so much so that we can often identify a bird species simply by hearing it sing. A behavior may have originated to fulfill a function different from the one it currently serves. For example, the song of a particular species may have first evolved to claim a territory but now is used to attract mates.

Tinbergen’s analysis allows us to see that different answers to the question “Why does a bird sing?” can all be correct. The first two, causation and development, are mechanistic explanations for behavior; these are referred to as proximate explanations of behavior because they deal with how the behavior came to be. The second two, adaptive function and evolutionary history, provide evolutionary explanations of how natural selection has shaped a behavior over time; these are referred to as ultimate explanations of behavior because they deal with why the behavior came to be. Tinbergen’s four questions are complementary ways of looking at the same problem, and are a good starting point for the analysis of behavior.

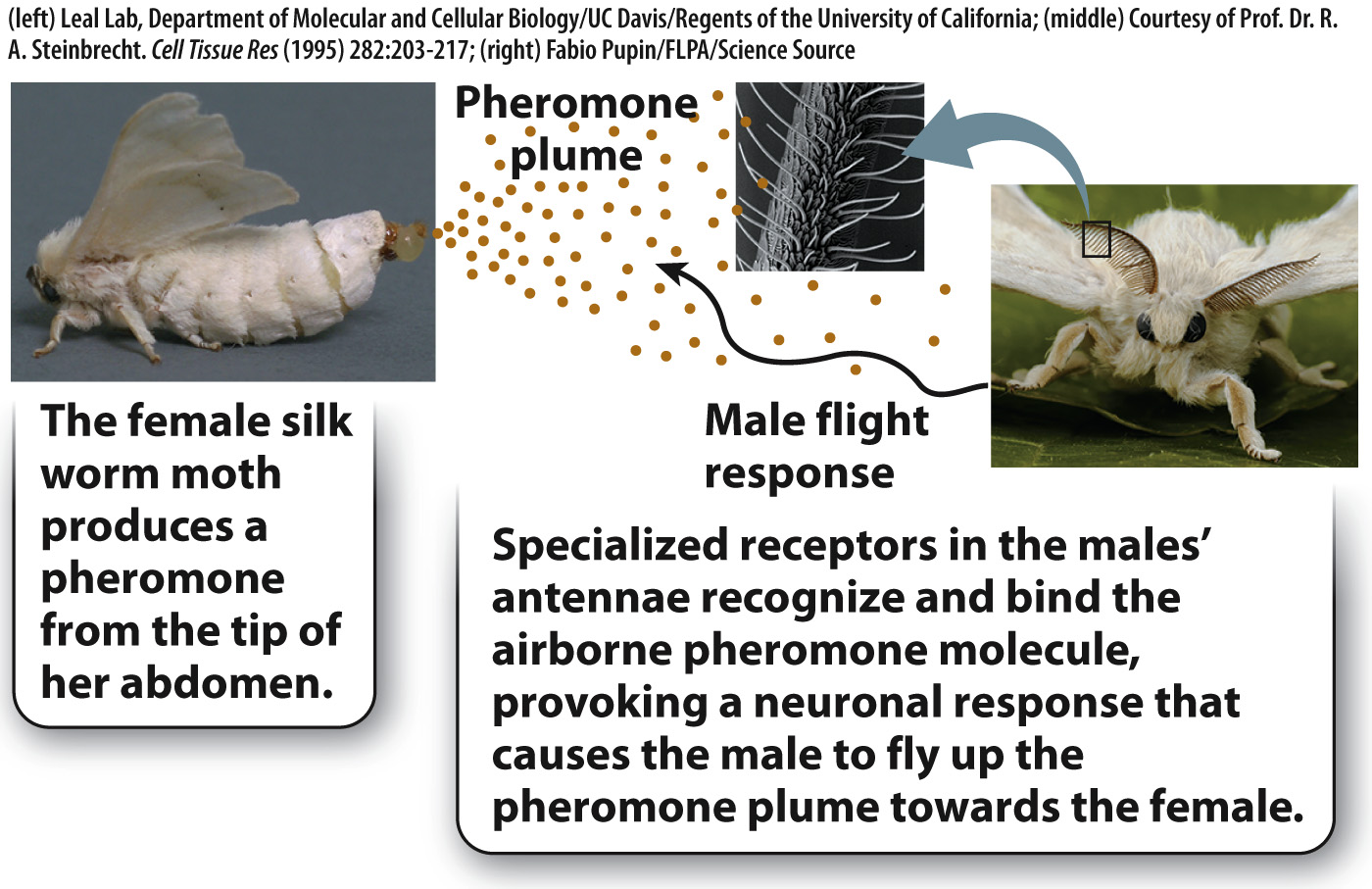

The answers to Tinbergen’s questions rely on an interplay between genes and the environment. The influence of genes is especially clear in innate behaviors, those that are instinctive and carried out regardless of earlier experience. Male silkworm moths of the genus Bombyx exhibit an innate behavior when they fly upwind toward the source of a female-

A particular behavior may depend on an individual’s experience, in which case the behavior has been learned. As we will see, even neurologically simple organisms have a considerable capacity to learn. Fruit flies, for example, learn to avoid certain locations or substances if they associate them with an unpleasant experience.

We can consider, then, the extent to which a particular behavior is genetically encoded (part of the animal’s nature) and the extent to which it is conditioned by the environment in which the animal develops (part of the animal’s nurture). However, as we discussed in Chapter 18, nature and nurture are inextricably linked. For example, most human behaviors are the product of an interaction between nature and nurture. Consider language in the context of Tinbergen’s second question concerning the development of behavior: We have an innate ability for acquiring language, but the specific language that we acquire depends entirely on our nurture. A baby in Italy learns Italian, and one in Finland learns Finnish.