45.6 Social Behavior

Returning to Tinbergen’s questions, we can consider further the adaptive function and evolutionary history of animal behavior. The evolutionary advantages of most behaviors are readily apparent. The imprinting of Lorenz’s goslings on the first moving object they encountered makes sense when you consider that that object is usually their parent (not Konrad Lorenz!) and that sticking close to their parent is an excellent survival strategy in a world filled with predators.

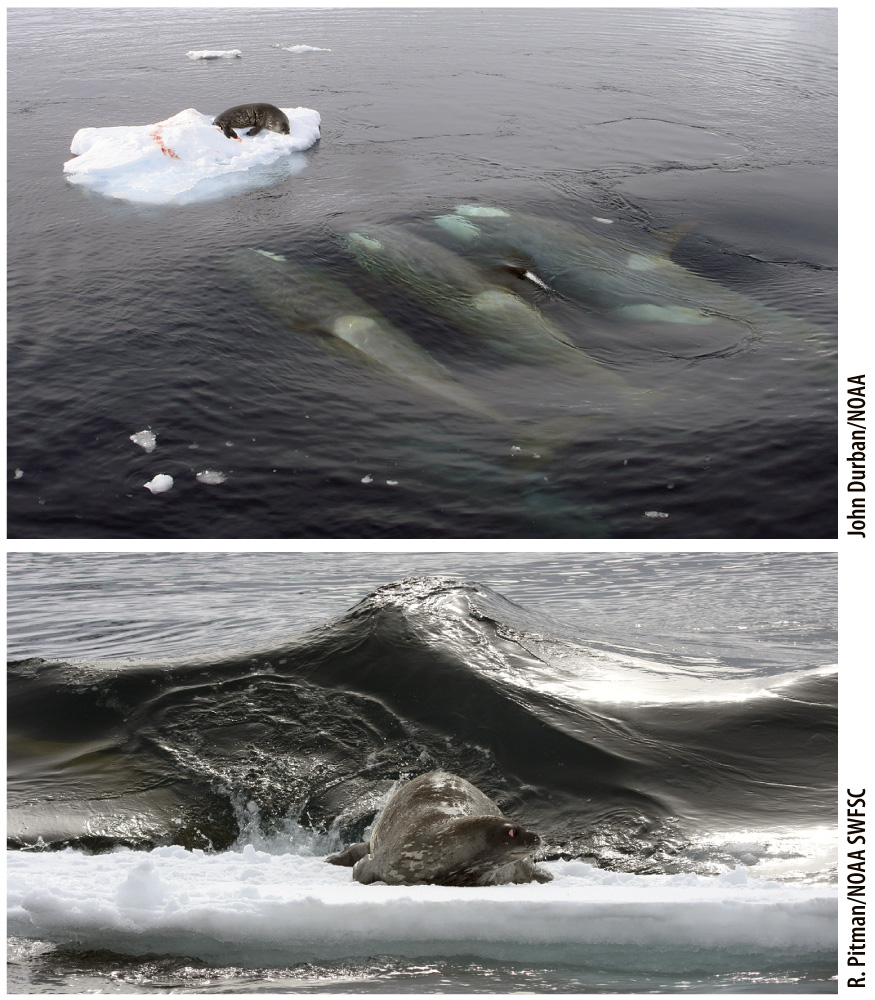

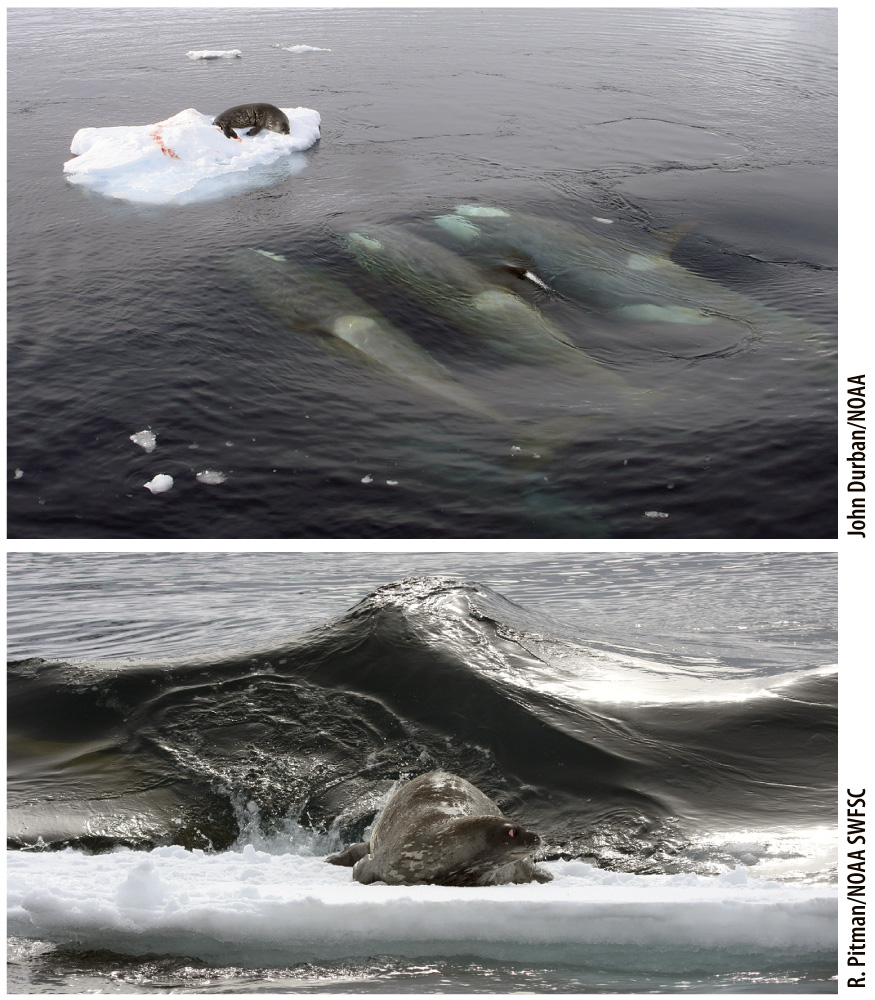

Social behaviors are also evolutionary advantageous. Consider the cooperative hunting seen in killer whales. Killer whales participate in a behavior called wave washing, in which a pod of whales collectively creates waves to wash a prey species—typically a seal—off an iceberg (Fig. 45.16). This behavior is collaborative, and it is clear why each individual participates. By itself, a single killer whale is incapable of generating a big enough wave, but, through cooperation, an individual can contribute to prey capture and gain some portion of the prey.

FIG. 45.16 Mutually beneficial cooperation. Killer whales cooperate to create a wave to wash prey off an iceberg.

Page 998

Sometimes, however, how a behavior enhances survival and reproduction is less clear. Perhaps the most prominent examples of this kind of behavior are sacrifices made by individuals apparently for the good of others. Formally, we describe an act of self-sacrifice that helps another as altruistic. Such acts seem to fly in the face of natural selection, which selects for traits that increase fitness and selects against traits that decrease fitness. But altruistic acts, by definition, decrease fitness and therefore should be selected against. This contradiction is particularly stark in the case of species like honeybees: Honeybee workers, which are females, do not reproduce but instead assist the reproduction of the queen. Darwin confessed that such behaviors caused him sleepless nights. How, Darwin wondered, could altruism arise?