The fixed action pattern is a stereotyped behavior.

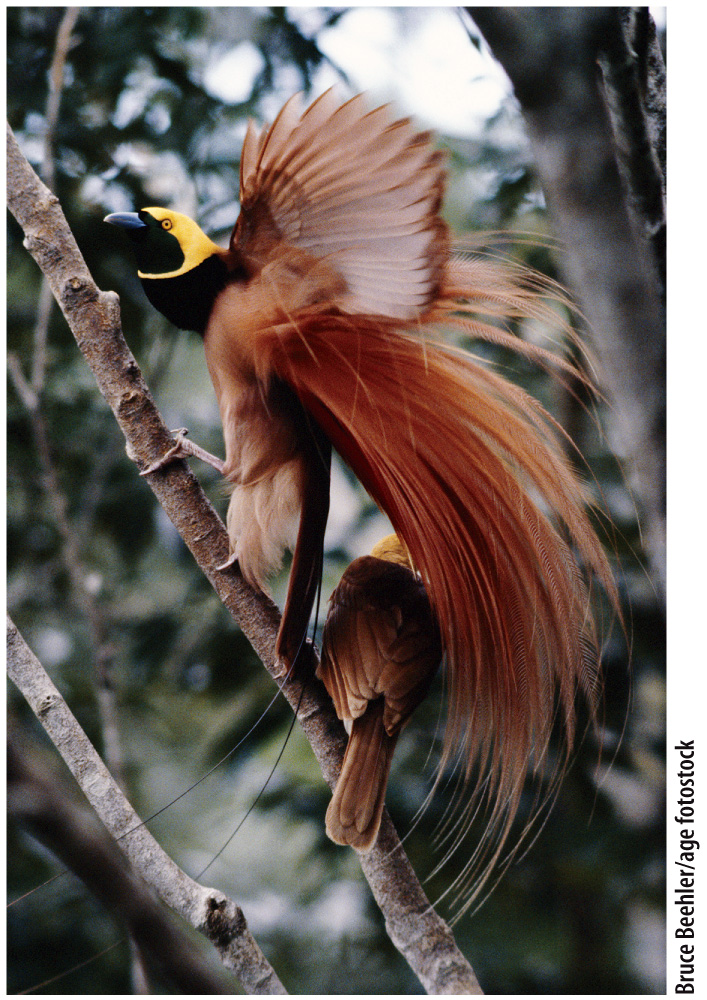

Some of the first behaviors to be carefully analyzed were displays, which are patterns of behavior that are species specific and tend to follow the same sequence of actions whenever they are repeated and in a way that is similar from one individual to the next. Because these behaviors are so similar whenever they are produced, they are considered “stereotyped.” Presumably, natural selection has favored display behaviors that are unmistakable in their function as signals. Consider, for example, courtship displays in birds that are preparing to mate (Fig. 45.2). Experiments have shown that, in some species, a bird raised in complete isolation from other members of its species will still perform a courtship display with great precision, suggesting that the behavior is genetically encoded, that is, instinctual rather than learned.

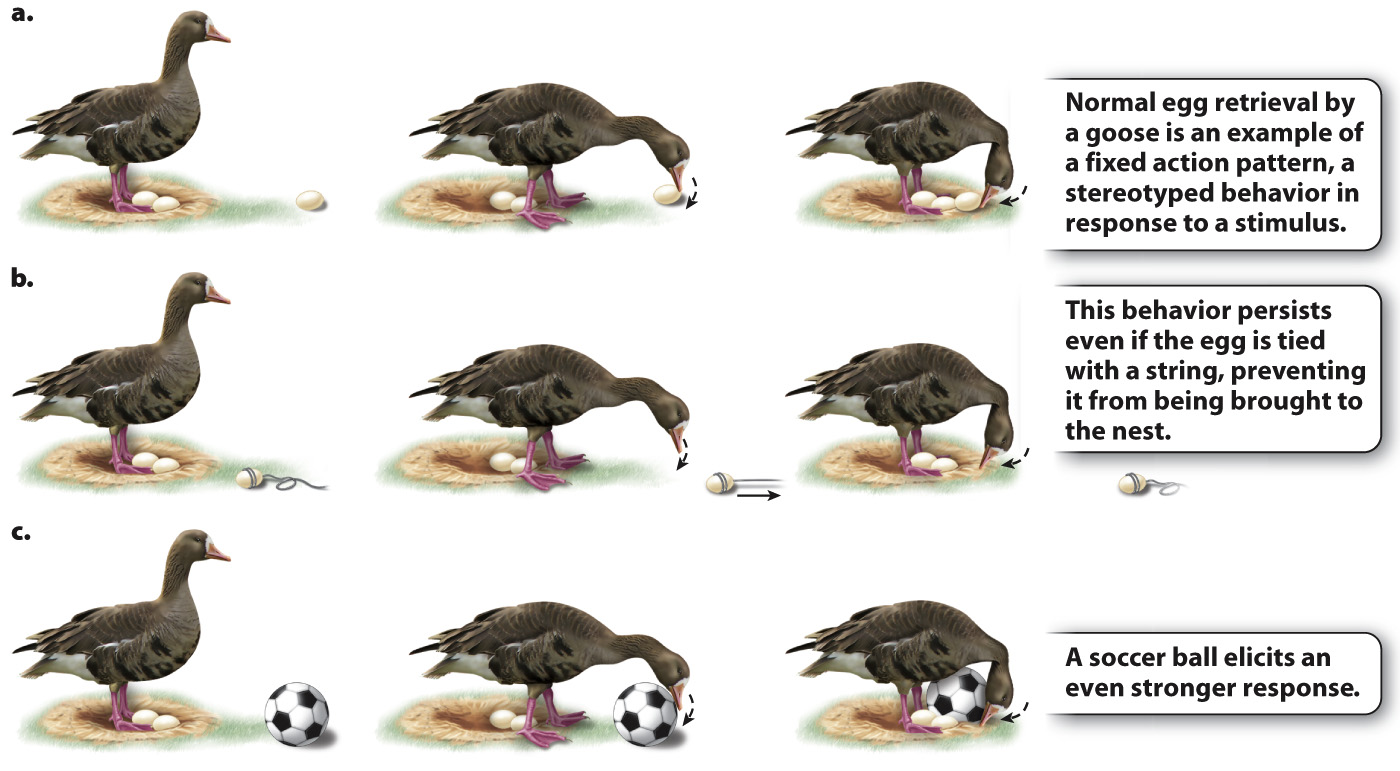

Many displays are fixed action patterns (FAPs), meaning that they consist of a sequence of behaviors that, once triggered, is followed through to completion. A classic example, originally studied by Tinbergen, is the response of a goose to an egg that has fallen from its nest (Fig. 45.3). The stimulus that initiates the behavior is the key stimulus and in this case it is the sight of the misplaced egg. This sight provokes in the goose an egg-

It is possible to understand this behavior by varying attributes of the key stimulus (in this case, the misplaced egg). A remarkable finding is that many birds respond most strongly to the largest round object provided, even a soccer ball, as illustrated in Fig. 45.3c. A soccer ball in fact not only elicits the egg-