Keystone species have disproportionate effects on communities.

While all or nearly all species in a given place have some effect on one another, the integrity of a community may depend on a single species. This situation can occur when one species influences the transfer of a large proportion of biomass and energy from one trophic level to another or when the species modifies its physical environment, as beavers do when they make ponds. Such pivotal populations are called keystone species because they support a community in much the way an architectural keystone supports an arch. Though all species contribute to the structure of a community, a keystone species affects other members of the community in ways that are disproportionate to its abundance or biomass.

A classic experiment by American zoologist Robert Paine gave birth to the concept of keystone species. Along the northwestern coast of the United States, mussels adhere to rocks in the intertidal zone, where they coexist with about two dozen other species of invertebrate animals and seaweeds. Mussel populations are regulated by their principal predator, a sea star called Pisaster ochraceus. When Paine removed the sea star from experimental plots, mussel populations exploded, outcompeting other animals and seaweeds for space and so eliminating them from the rocky shoreline. Control plots in which the sea star remained showed no such change. From these results, Paine concluded that the activities of the predatory sea star had a singularly strong influence on the diversity and distribution of other populations in the rocky intertidal community. Pisaster ochraceus is a keystone species.

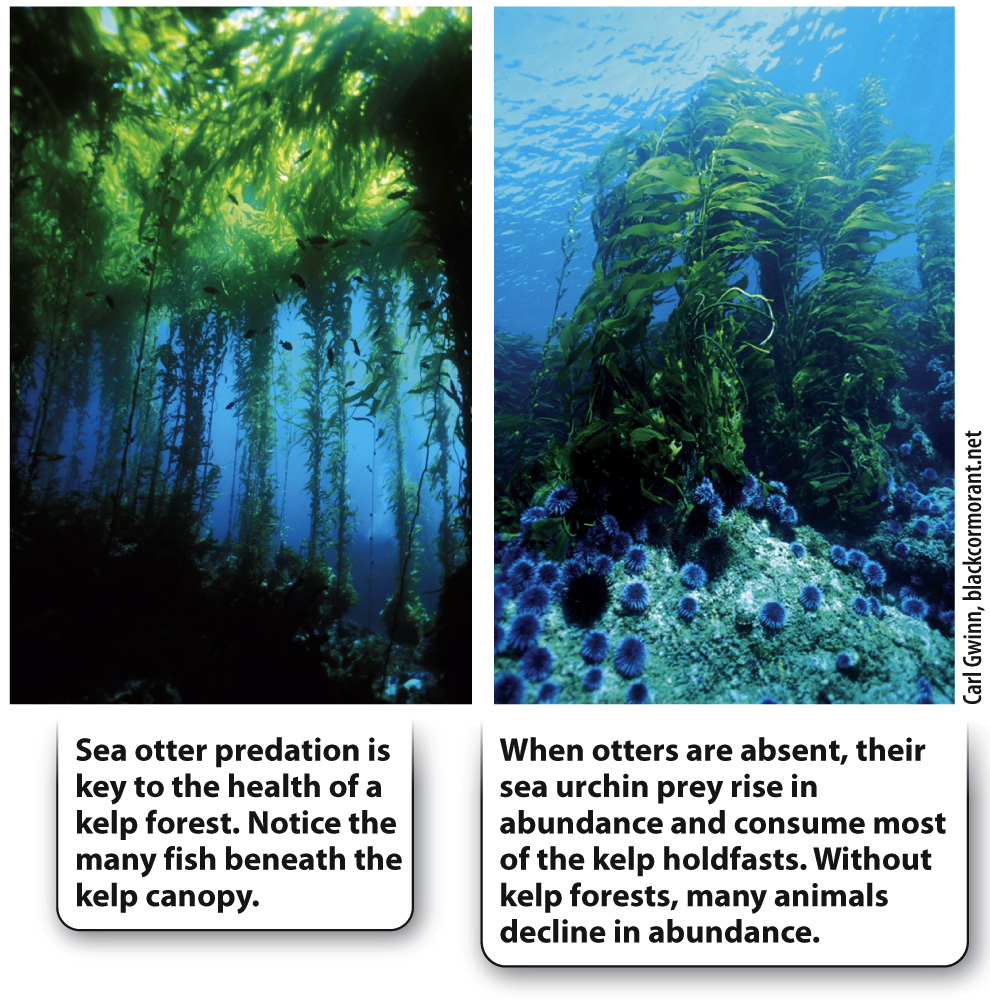

Another experiment, this time unintended, cements the point. Along the west coast of the United States and Canada, giant kelp grow more than 50 m tall, providing a home for a remarkable diversity of fish and invertebrates (Fig. 47.12). The kelp community depends strongly on a single predator: the sea otter. Sea otters are the predators of sea urchins, which graze on the rootlike holdfasts that anchor kelp to the seafloor. When the otters were removed by overhunting decades ago, sea urchin abundance soared and the kelp nearly disappeared, along with many other populations that live in kelp forests. Now, where otters are protected they once again keep urchin populations in check, enabling the kelp to return, and along with it, the diversity of fish and other animals for which kelp provides a habitat.

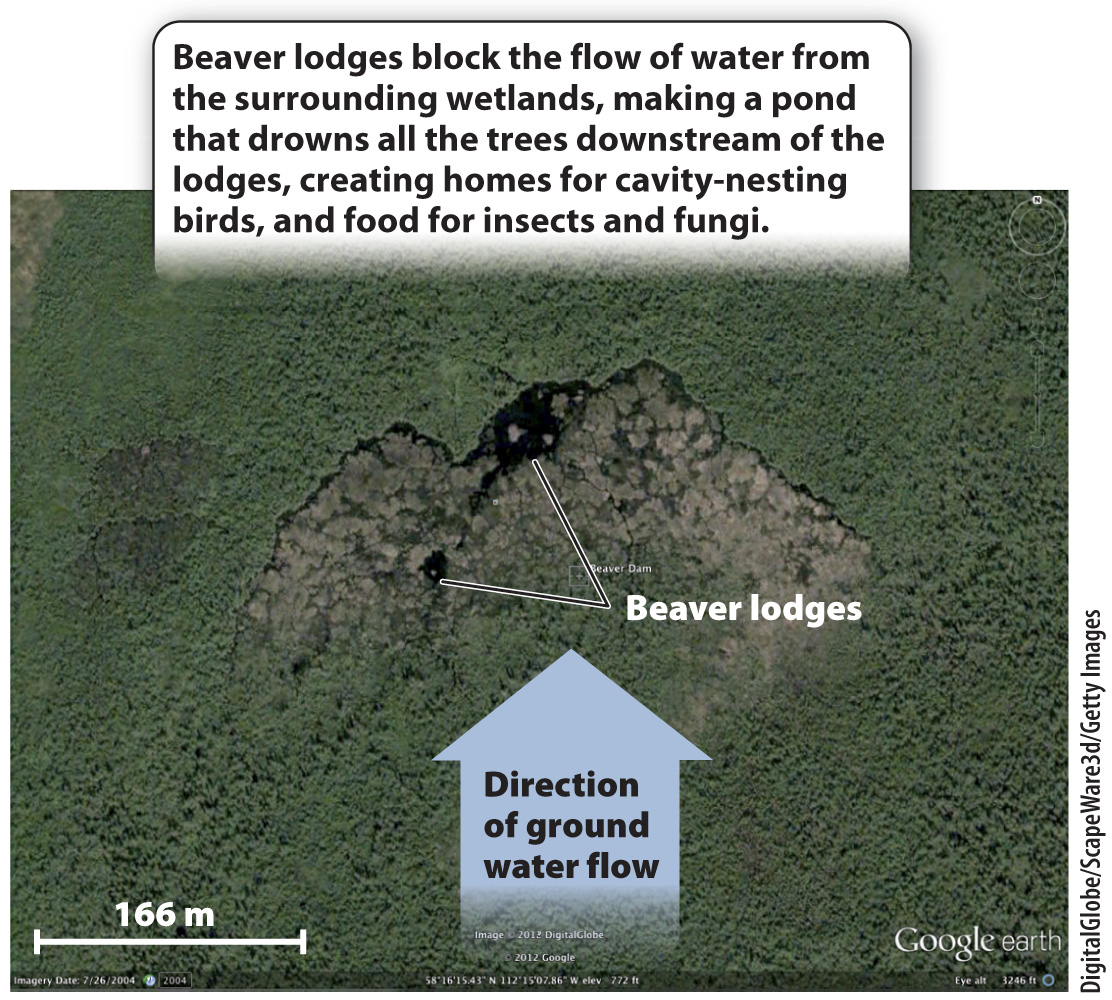

Keystone species called ecosystem engineers actively shape the physical environment, creating habitat for others. The classic example is beavers, which produce ponds by damming streams in forests, creating habitat that would not otherwise exist (Fig. 47.13). Hippos provide another good example, only recently recognized. In East Africa, hippos loll about in rivers and lakes during the day, but venture onto the land at night to feed on grasses and other low-

Quick Check 4 Lemmings affect many other species in the Bylot Island community. Why are lemmings not considered a keystone species?

Quick Check 4 Answer

Although they can affect many other species in the Arctic, lemmings are not a keystone species because their effects are a function of their great abundance. Keystone species have effects on communities that are disproportionate to their numbers because of the particular roles they play, often as predators.