Succession describes the community response to new habitats or disturbance.

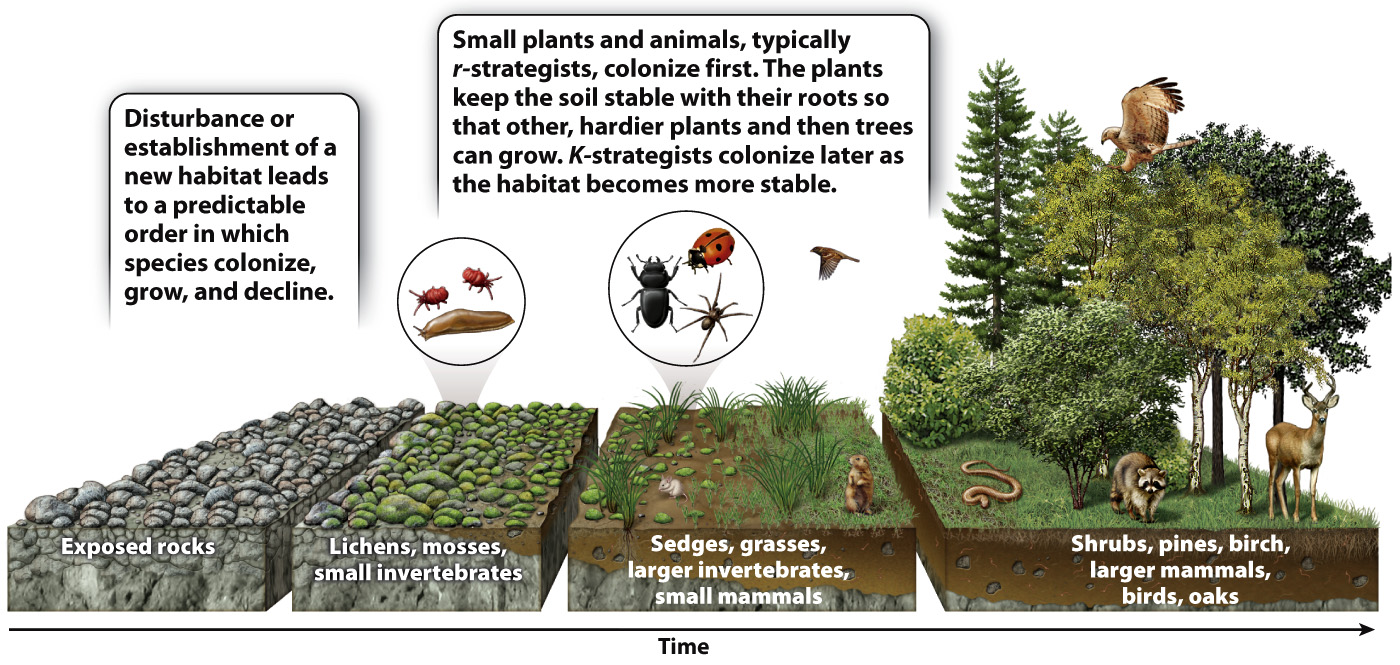

Following disturbance or the appearance of a new habitat, a community goes through a series of changes. These changes involve a predictable sequence of colonization of species that then transform the community, in what can appear to be a linear process of maturation. For example, when a lava flow cools, the first organisms to colonize the rock are lichens and mosses that begin the slow process of soil formation. They are followed by grasses and other small plants, and by tiny arthropods and eventually larger animals and woody plants that eventually shade out the mosses and lichens that started the process of colonization. Similarly, following a large storm or fire, newly vacated habitat is commonly colonized by plant species adapted for rapid growth and strong sun. Eventually, these species are replaced by others able to grow in increasing shade. The pace of this transformation may be rapid, occurring over a few decades, or it may be much slower, depending on the environment.

This process of species replacing each other in time is called succession (Fig. 47.14). Clements viewed the pattern of species replacement in succession as strong evidence in support of his view that communities are highly integrated. Gleason, in contrast, explained succession purely in terms of the habitat preferences of individual populations.

The Pin Cherry, a resident of New England forests, illustrates how the life histories of individual species can contribute to succession. If you walk through a forest in New Hampshire, you will see oak trees and beeches, pine and hemlock. A mature forest may contain few or no Pin Cherry trees, but if you examine seeds lying dormant within the forest soil, you will see numerous Pin Cherry seeds. How did they get there?

Years earlier, disturbance from a storm or fire opened up the forest floor and Pin Cherries established themselves in the sunlit soils, growing from seeds left in the droppings of birds that had consumed the cherries elsewhere. The seedlings of Pin Cherries grow well in full sunlight, so the trees grew rapidly to reproductive maturity. A forest canopy was eventually reestablished, and Pin Cherry seeds do not germinate in the shade. But oak seedlings prosper in shade, so, through time, oaks and other species came to dominate this patch of forest. They will continue to dominate it until the next disturbance, when the removal of mature trees will once more expose the forest floor to bright sunlight, literally giving Pin Cherries another day in the sun.

The succession of species reflects the adaptations of each to the changes in sunlight, soil, water, and space that occur as the first organisms arrive, mature, and die. These organisms’ bodies influence their habitat in both life and death, whether aquatic or terrestrial. Succession over thousands of years can turn bare rock into forest. Lichens are often the first organisms to colonize bare rock newly formed by cooling lava or exposed by landslides. The lichens may start off with only a few mites and other tiny invertebrates living on them. As the stone weathers, and microorganisms feed on the lichen and one another, they form particles of soil that accumulate in cracks and crevices. Eventually, small plants, such as sedges and grasses, take root, and the growing plant community begins to gain height and diversity as other plants establish themselves.

Soon, larger insects, spiders, and other invertebrates join the community, as well as the first small mammals and birds. Many of these early colonizing species are r-

The first sun-