Competitive exclusion can prevent two species from occupying the same niche at the same time.

In general, when two species have overlapping niches (if, for example, they share a physical habitat and overlap strongly in resource use), one will either become extinct in that place or change its niche. Coyotes and foxes eat the same small prey, but when they meet, a coyote will waste energy by chasing the fox, and the fox loses energy by running away from the coyote. In regions where foxes and coyotes occur together, the foxes avoid interactions with the larger coyotes by leaving the area, placing their dens in locations where coyotes do not occur.

This result of such an interaction, in which competition between two species prevents one from occupying a particular niche, is called competitive exclusion. It is another way in which a fundamental niche can be reduced to a smaller realized niche. It is important to recognize that even if two species overlap substantially in resource use, competitive exclusion may not take place unless the population sizes of both species are large enough to encounter each other or reduce the resources available.

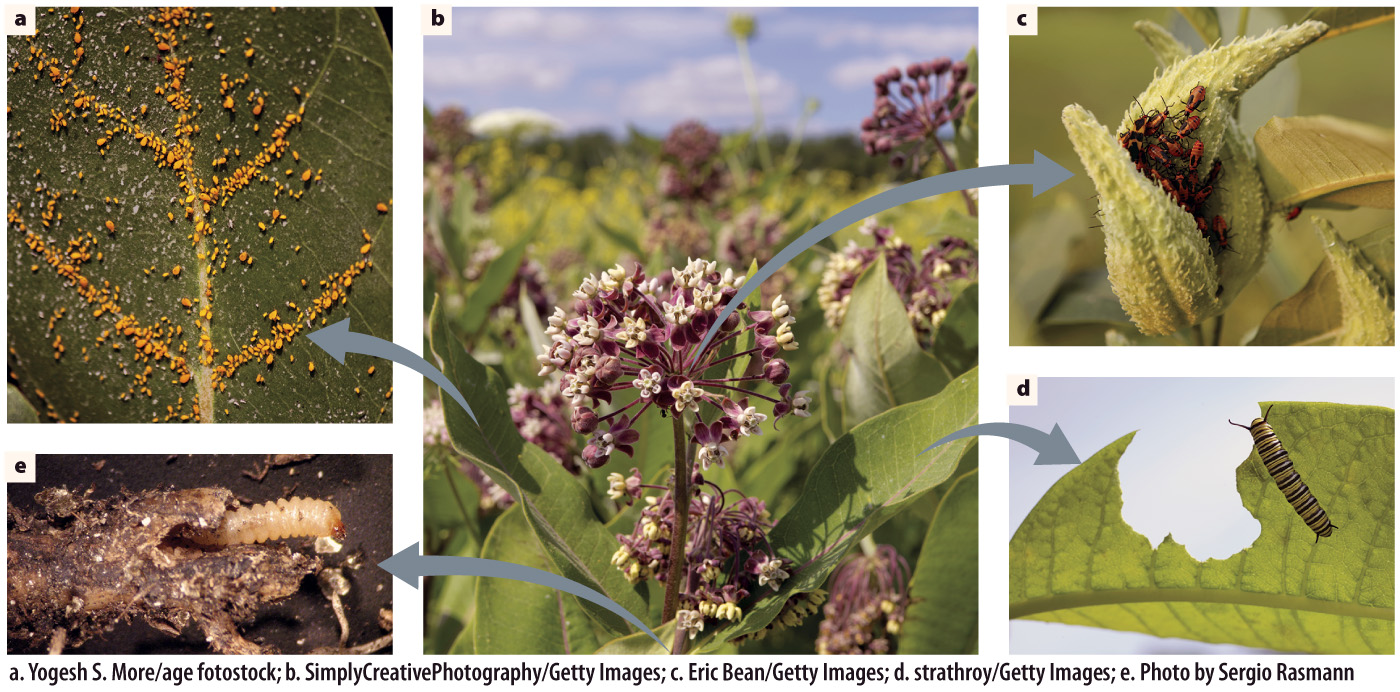

Competitive exclusion can be more complicated than competition between two species that forces the two groups to use two different resources. Consider for example the variety of insect groups that can make use of different resources on just one species of plant. The insects feeding on a single patch of milkweed usually include some species of beetle that nibble roots and others that chew on leaf edges along with caterpillars. Some aphids suck phloem contents from the stems, and other beetle species feed on the plant’s seeds (Fig. 47.3).

We may interpret this specialization on different parts of the milkweed as competitive exclusion, but it’s possible that the insects feed on different parts of the plant either because they competed for milkweeds in the distant evolutionary past and have long since diverged in niches, or because each has evolved its unique association with a particular plant part long before they were associated with milkweeds. In either case, there is no direct competition today among the current species.