Heat is transported toward the poles by wind and ocean currents.

Temperatures at the equator are actually a bit cooler than we might predict based on how directly solar radiation strikes Earth at that latitude; and the poles are somewhat warmer than a diagram of solar radiation like Fig. 48.1 would predict. To reconcile predicted and measured temperatures, we need to consider another set of processes, those that transport heat from low to high latitudes. This heat transport is carried out by wind and ocean currents.

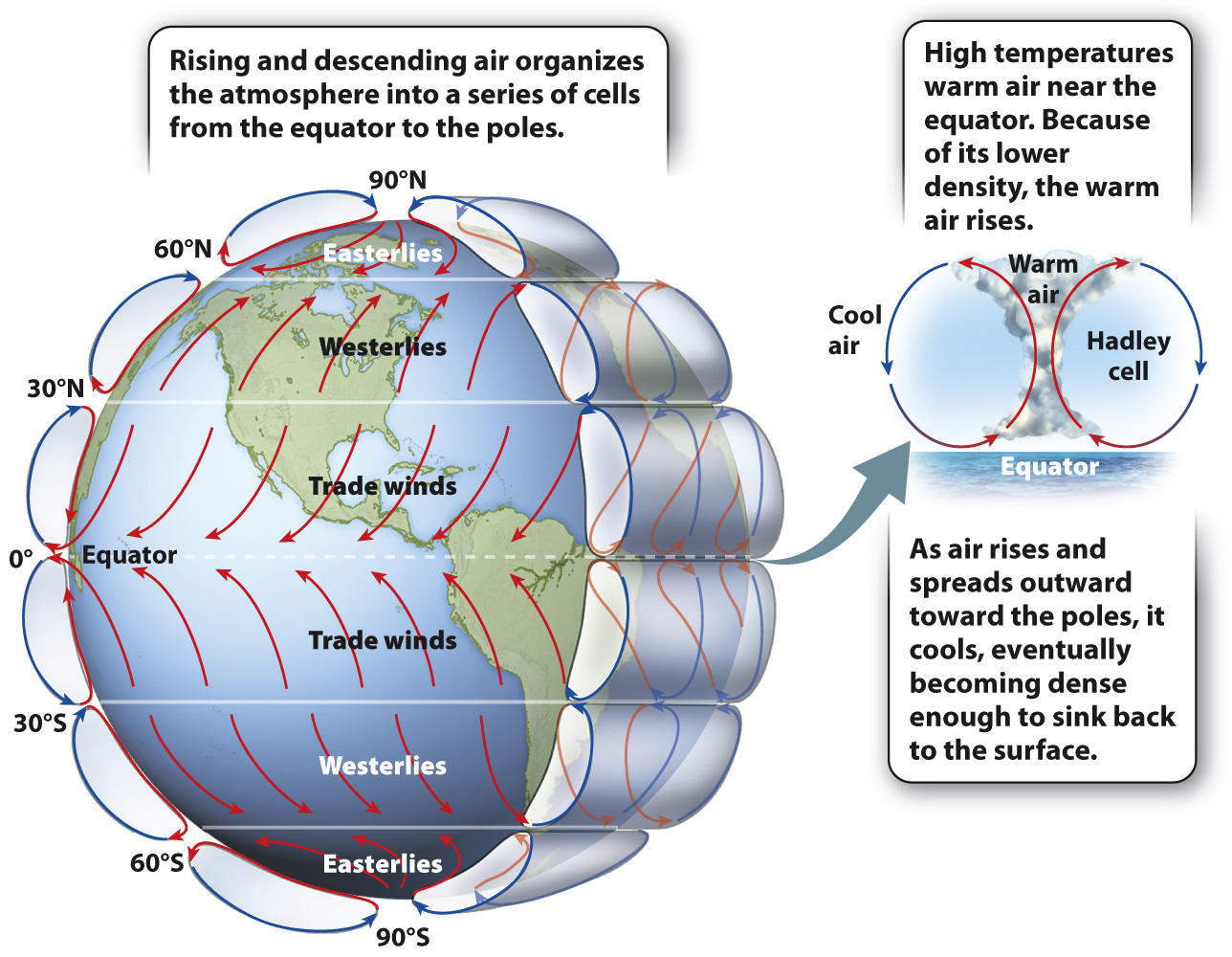

The gas molecules that make up air are constantly in motion, and when they are heated they move faster, and (unless confined) the volume of the air expands. For this reason, warm air is less dense than colder air and so it rises through the atmosphere. Not surprisingly, the rise of warm air is particularly strong at the equator (Fig. 48.3). The air cools as it rises, and, once it reaches an altitude of 10–

As warm air expands upward, cool air moves in to replace it. We experience this movement as wind, and as sailors have known for thousands of years, the prevailing direction of the wind differs from one latitude to another (Fig. 48.3). Prevailing winds reflect those cells of rising and falling air, but to understand them more fully, we have to consider one further aspect of our planet: its rotation about an axis.

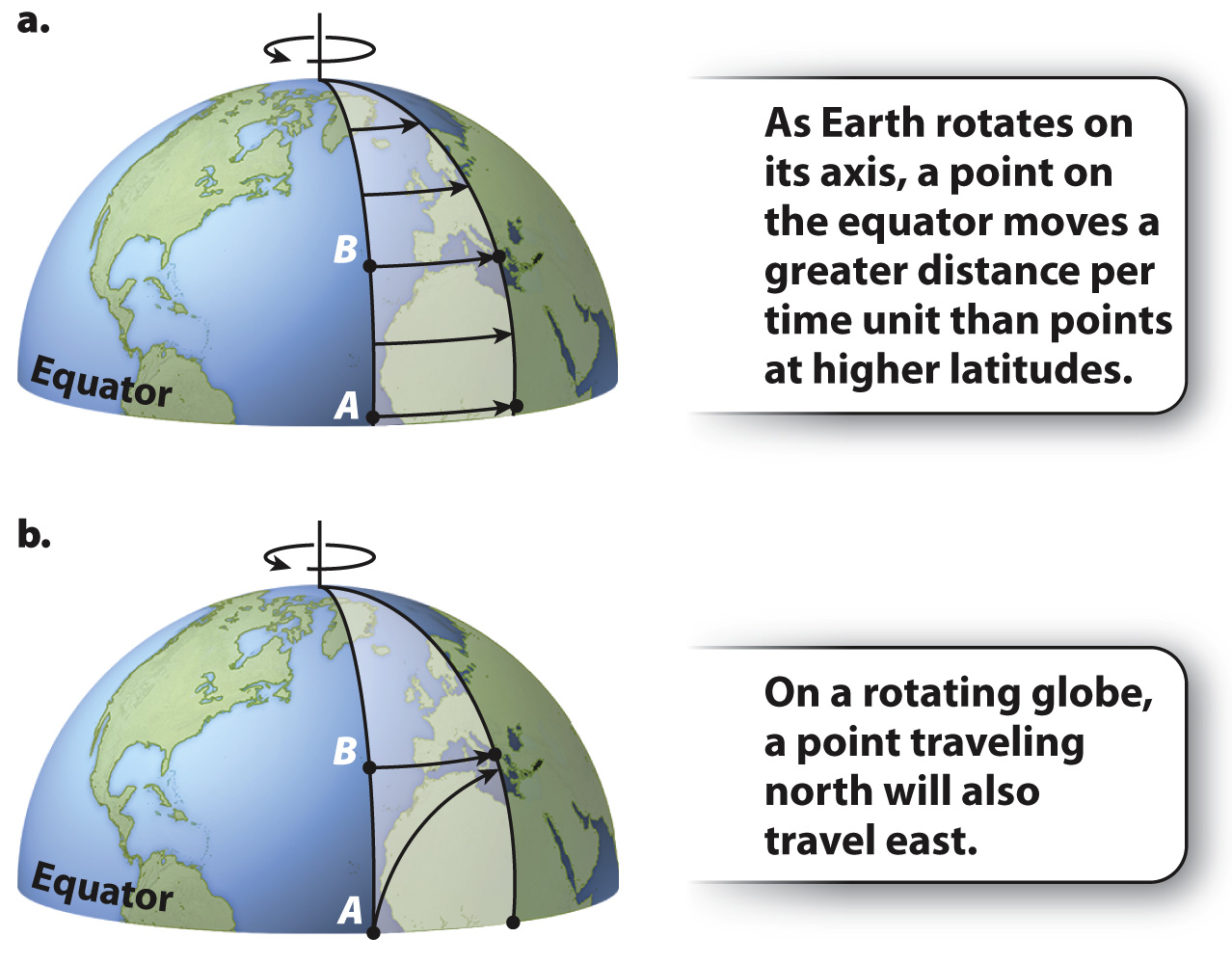

Earth rotates in a counterclockwise direction, moving from west to east. In the course of one daily rotation, a spot at the equator will move through a distance equivalent to our planet’s circumference—

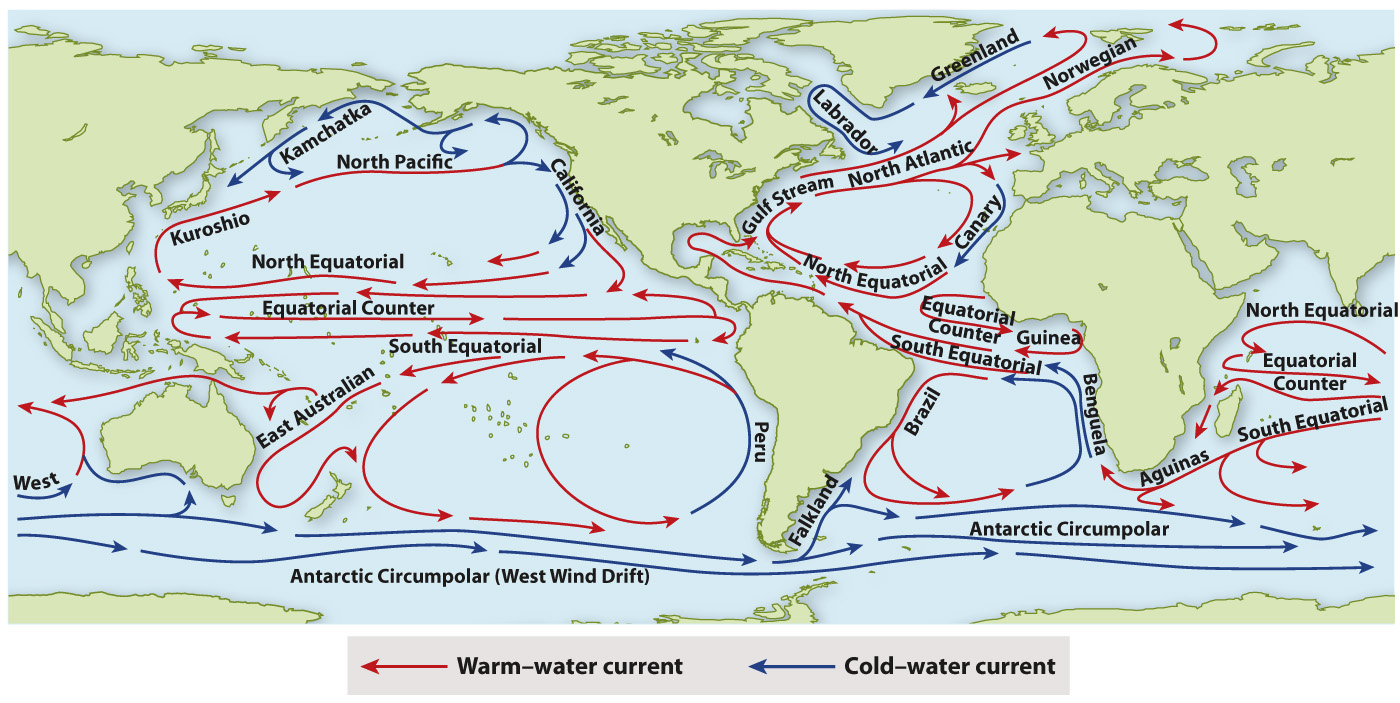

Winds, in turn, push on water in the oceans, directing surface currents as shown in Fig. 48.5. Water can carry much more heat than air, and so ocean currents transport a great deal of heat to higher latitudes. For example, the ocean current known as the Gulf Stream (and its northeasterly extension, the North Atlantic Drift) transports warm water north along the eastern margin of North America and then east toward Europe. The heat it carries helps to keep northwestern Europe much warmer than land at equivalent latitudes in North America. Subtropical plants ornament gardens in coastal Scotland but would be unthinkable in Newfoundland, Canada, which is at approximately the same latitude.

Just as colder air sinks below warmer and less dense air, cold waters sink beneath less dense water masses. At high latitudes, the sinking cold waters begin to move slowly along the seafloor toward the equator. The result is a complex three-

Wind and water, then, transfer heat from the equator toward the poles, modifying the direct effects of solar radiation. Together, these processes result in the temperature distribution observed across the planet, explaining why palm trees that cannot tolerate freezing are confined to low latitudes, while deciduous trees that lose their leaves every fall occur mostly in the seasonal climates found at mid-