11.1 Basic Motivational Concepts

11-

Psychologists define motivation as a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior. Our motivations arise from the interplay between nature (the bodily “push”) and nurture (the “pulls” from our thought processes and culture). Consider four perspectives for viewing motivated behaviors:

- Instinct theory (now replaced by the evolutionary perspective) focuses on genetically predisposed behaviors.

- Drive-reduction theory focuses on how we respond to our inner pushes.

- Arousal theory focuses on finding the right level of stimulation.

- And Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs focuses on the priority of some needs over others.

motivation a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior.

Instincts and Evolutionary Psychology

instinct a complex behavior that is rigidly patterned throughout a species and is unlearned.

Early in the twentieth century, as Charles Darwin’s influence grew, it became fashionable to classify all sorts of behaviors as instincts. If people criticized themselves, it was because of their “self-

To qualify as an instinct, a complex behavior must have a fixed pattern throughout a species and be unlearned (Tinbergen, 1951). Such behaviors are common in other species (recall imprinting in birds and the return of salmon to their birthplace). Some human behaviors, such as infants’ innate reflexes for rooting and sucking, also exhibit unlearned fixed patterns, but many more are directed by both physiological needs and psychological wants.

Instinct theory failed to explain most human motives, but its underlying assumption continues in evolutionary psychology: Genes do predispose some species-

421

Drives and Incentives

drive-reduction theory the idea that a physiological need creates an aroused tension state (a drive) that motivates an organism to satisfy the need.

homeostasis a tendency to maintain a balanced or constant internal state; the regulation of any aspect of body chemistry, such as blood glucose, around a particular level.

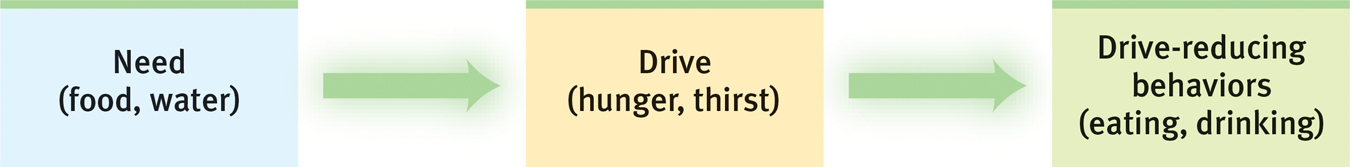

When the original instinct theory of motivation collapsed, it was replaced by drive-reduction theory—the idea that a physiological need (such as for food or water) creates an aroused state that drives the organism to reduce the need. With few exceptions, when a physiological need increases, so does a psychological drive—an aroused, motivated state.

The physiological aim of drive reduction is homeostasis—the maintenance of a steady internal state. An example of homeostasis (literally “staying the same”) is the body’s temperature-

Figure 11.1

Figure 11.1Drive-

incentive a positive or negative environmental stimulus that motivates behavior.

Not only are we pushed by our need to reduce drives, we also are pulled by incentives—positive or negative environmental stimuli that lure or repel us. This is one way our individual learning histories influence our motives. Depending on our learning, the aroma of good food, whether fresh roasted peanuts or toasted ants, can motivate our behavior. So can the sight of those we find attractive or threatening.

When there is both a need and an incentive, we feel strongly driven. The food-

Optimum Arousal

We are much more than homeostatic systems, however. Some motivated behaviors actually increase arousal. Well-

422

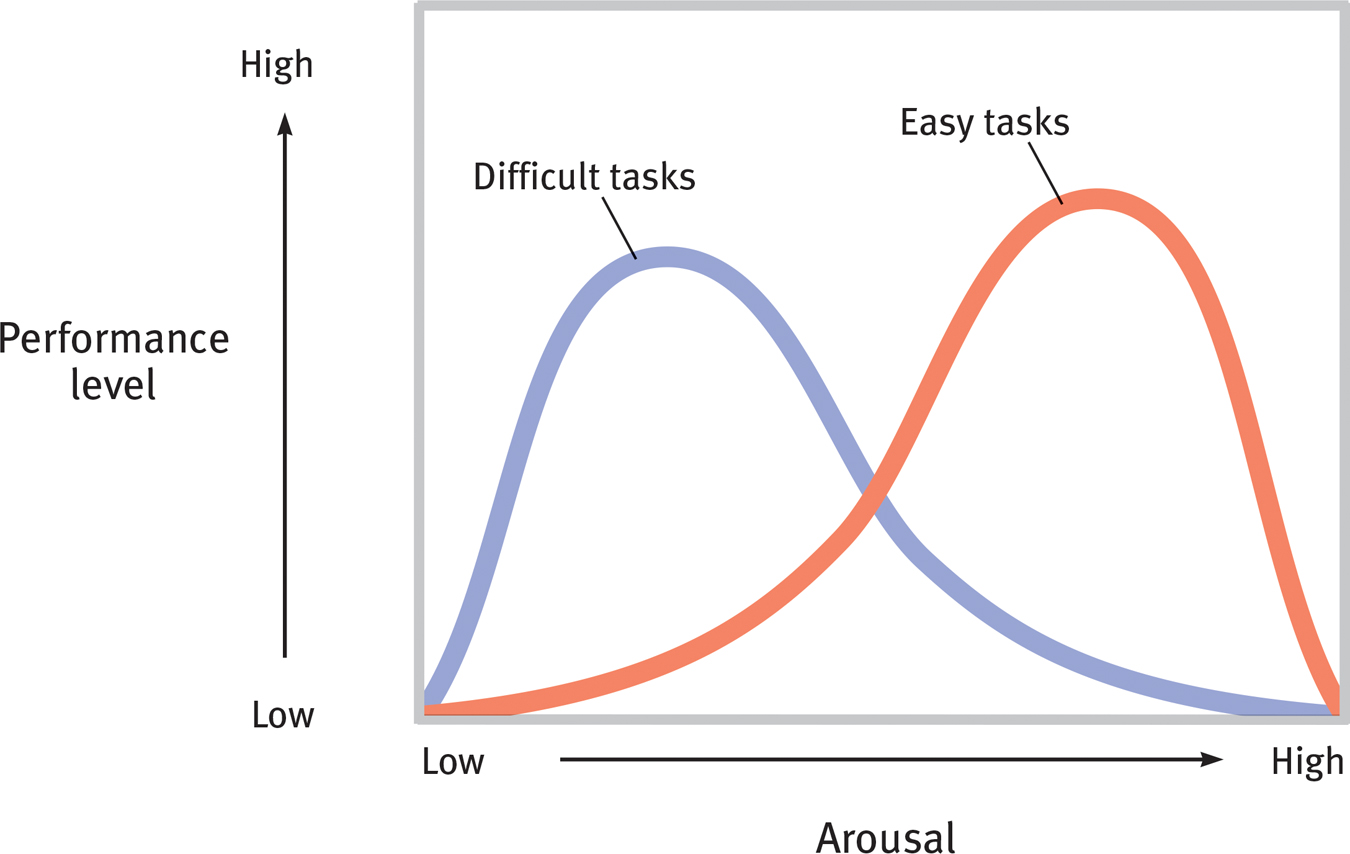

Yerkes-Dodson law the principle that performance increases with arousal only up to a point, beyond which performance decreases.

So, human motivation aims not to eliminate arousal but to seek optimum levels of arousal. Having all our biological needs satisfied, we feel driven to experience stimulation and we hunger for information. Lacking stimulation, we feel bored and look for a way to increase arousal to some optimum level. However, with too much stimulation comes stress, and we then look for a way to decrease arousal.

Two early-

Figure 11.2

Figure 11.2Arousal and performance

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Performance peaks at lower levels of arousal for difficult tasks, and at higher levels for easy or well-learned tasks. (1) How might this phenomenon affect runners? (2) How might this phenomenon affect anxious test-takers facing a difficult exam? (3) How might the performance of anxious students be affected by relaxation training?

(1) Runners tend to excel when aroused by competition. (2) High anxiety in test-

A Hierarchy of Motives

“Hunger is the most urgent form of poverty.”

Alliance to End Hunger, 2002

Some needs take priority. At this moment, with your needs for air and water hopefully satisfied, other motives—

Small psychological world: Abraham Maslow was the first graduate student of the famed monkey attachment researcher, Harry Harlow. (Harlow, in turn, had been mentored at Stanford by the famed intelligence researcher, Lewis Terman.)

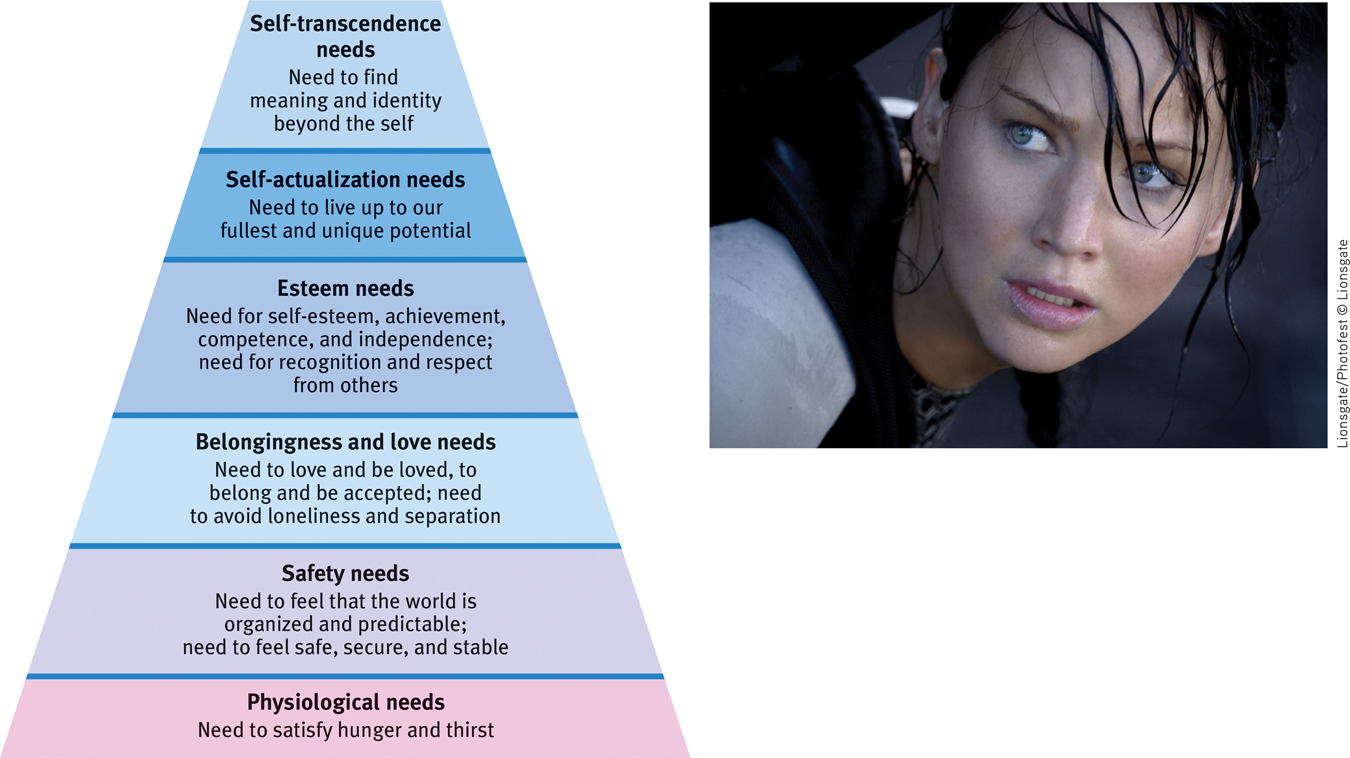

hierarchy of needs Maslow’s pyramid of human needs, beginning at the base with physiological needs that must first be satisfied before higher-level safety needs and then psychological needs become active.

Abraham Maslow (1970) described these priorities as a hierarchy of needs (FIGURE 11.3). At the base of this pyramid are our physiological needs, such as those for food and water. Only if these needs are met are we prompted to meet our need for safety, and then to satisfy our human needs to give and receive love and to enjoy self-

Figure 11.3

Figure 11.3Maslow’s hierarchy of needs Reduced to near-

Near the end of his life, Maslow proposed that some people also reach a level of self-

423

Maslow’s hierarchy is somewhat arbitrary; the order of such needs is not universally fixed. People have starved themselves to make a political statement. Culture also matters: Self-

Nevertheless, the simple idea that some motives are more compelling than others provides a framework for thinking about motivation. Worldwide life-

Let’s now consider four representative motives, beginning at the physiological level with hunger and working up through sexual motivation to the higher-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do instinct theory, drive-reduction theory, and arousal theory contribute to our understanding of motivated behavior?

Instincts and evolutionary psychology help explain the genetic basis for our unlearned, species-

- After hours of driving alone in an unfamiliar city, you finally see a diner. Although it looks deserted and a little creepy, you stop because you are really hungry. How would Maslow’s hierarchy of needs explain your behavior?

According to Maslow, our drive to meet the physiological needs of hunger and thirst take priority over safety needs, prompting us to take risks at times in order to eat.

424

REVIEW: Basic Motivational Concepts

|

REVIEW | Basic Motivational Concepts |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

11-

Motivation is a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior. The instinct/evolutionary perspective explores genetic influences on complex behaviors. Drive-reduction theory explores how physiological needs create aroused tension states (drives) that direct us to satisfy those needs. Environmental incentives can intensify drives. Drive-reduction’s goal is homeostasis, maintaining a steady internal state. Arousal theory proposes that some behaviors (such as those driven by curiosity) do not reduce physiological needs but rather are prompted by a search for an optimum level of arousal. The Yerkes-Dodson law states that performance increases with arousal, but only to a certain point, after which it decreases. Performance peaks at lower levels of arousal for difficult tasks, and at higher levels for easy or well-learned tasks. Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs proposes a pyramid of human needs, from basic needs such as hunger and thirst up to higher-level needs such as self-actualization and self-transcendence.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

motivation instinct drive-reduction theory homeostasis incentive Yerkes-Dodson law hierarchy of needs | the idea that a physiological need creates an aroused tension state (a drive) that motivates an organism to satisfy the need. Maslow’s pyramid of human needs, beginning at the base with physiological needs that must first be satisfied before higher-level safety needs and then psychological needs become active. a complex behavior that is rigidly patterned throughout a species and is unlearned. a positive or negative environmental stimulus that motivates behavior. a tendency to maintain a balanced or constant internal state; the regulation of any aspect of body chemistry, such as blood glucose, around a particular level. a need or desire that energizes and directs behavior. the principle that performance increases with arousal only up to a point, beyond which performance decreases. |

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.