15.3 Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorder

15-

Most of us will have some direct or indirect experience with depression. If you are like many college students, at some time during this year—

“My life had come to a sudden stop. I was able to breathe, to eat, to drink, to sleep. I could not, indeed, help doing so; but there was no real life in me.”

Leo Tolstoy, My Confession, 1887

Joy, contentment, sadness, and despair exist at different points on a continuum, points at which any of us may find ourselves at any given moment. To feel bad in reaction to profoundly sad events is to be in touch with reality. In such times, there is an up side to being down. Sadness is like a car’s low-

“If someone offered you a pill that would make you permanently happy, you would be well advised to run fast and run far. Emotion is a compass that tells us what to do, and a compass that is perpetually stuck on NORTH is worthless.”

Daniel Gilbert, “The Science of Happiness,” 2006

But sometimes this response, taken to an extreme, can become seriously maladaptive and signal a disorder. The difference between a blue mood after bad news and a depression-

In this section, we consider three disorders in which depression impairs daily living:

- Major depressive disorder, a persistent state of hopelessness and lethargy

- Persistent depressive disorder, in which a person experiences milder depressive feelings

- Bipolar disorder (formerly called manic-depressive disorder), in which a person alternates between depression and overexcited hyperactivity

629

Major Depressive Disorder

major depressive disorder a disorder in which a person experiences, in the absence of drugs or another medical condition, two or more weeks with five or more symptoms, at least one of which must be either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure.

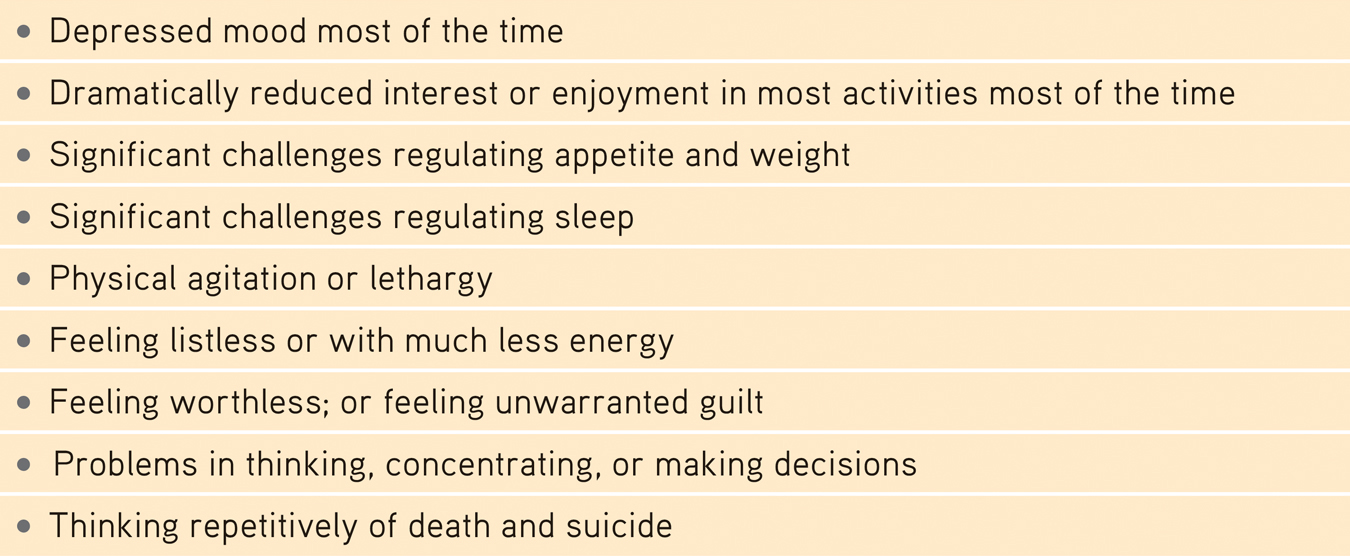

Major depressive disorder occurs when at least five signs of depression last two or more weeks (TABLE 15.5). The symptoms must cause near-

Table 15.5

Table 15.5Diagnosing Major Depressive Disorder

The DSM-

To sense what major depression feels like, suggest some clinicians, imagine combining the anguish of grief with the sluggishness of bad jet lag. If stress-

Adults diagnosed with persistent depressive disorder (also called dysthymia) experience a mildly depressed mood more often than not for two years or more (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). They also display at least two of the following symptoms:

- Difficulty with decision-making and concentration

- Feeling hopeless

- Poor self-esteem

- Reduced energy levels

- Problems regulating sleep

- Problems regulating appetite

Bipolar Disorder

mania a hyperactive, wildly optimistic state in which dangerously poor judgment is common.

bipolar disorder a disorder in which a person alternates between the hopelessness and lethargy of depression and the overexcited state of mania. (Formerly called manic-depressive disorder.)

With or without therapy, episodes of major depression usually end, and people temporarily or permanently return to their previous behavior patterns. However, some people rebound to, or sometimes start with, the opposite emotional extreme—

Adolescent mood swings, from rage to bubbly, can, when prolonged, lead to a bipolar diagnosis. Between 1994 and 2003, diagnoses of bipolar disorder swelled. U.S. National Center for Health Statistics annual physician surveys revealed an astonishing 40-

630

During the manic phase, people with bipolar disorder typically have little need for sleep. They show fewer sexual inhibitions. Their positive emotions persist abnormally (Gruber, 2011; Gruber et al., 2013). Their speech is loud, flighty, and hard to interrupt. They find advice irritating. Yet they need protection from their own poor judgment, which may lead to reckless spending or unsafe sex. Thinking fast feels good, but it also increases risk taking (Chandler & Pronin, 2012; Pronin, 2013).

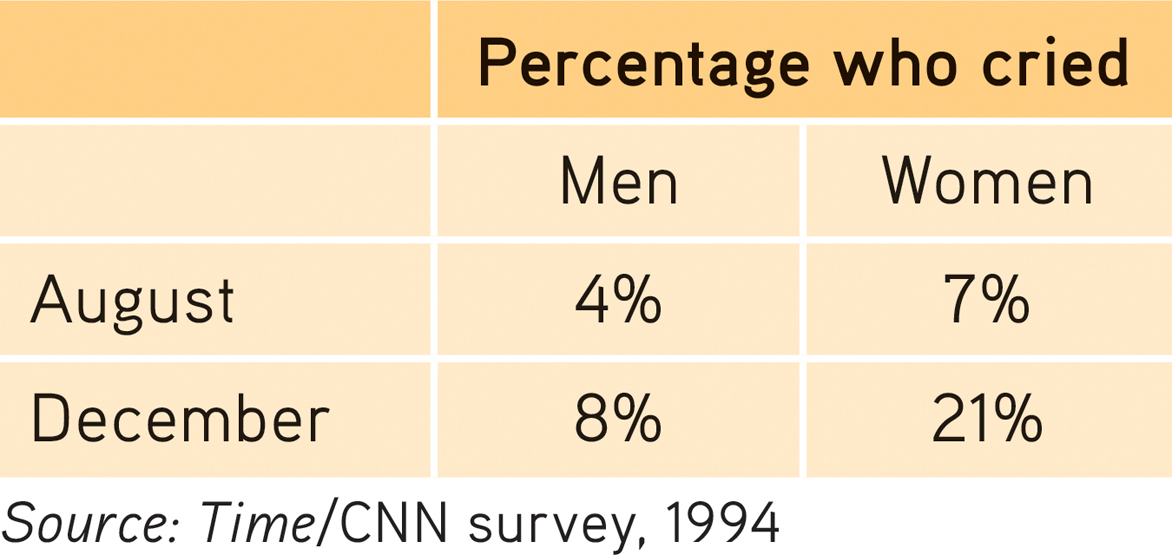

For some people suffering depressive disorders or bipolar disorder, symptoms may have a seasonal pattern. Depression may regularly return each fall or winter, and mania (or a reprieve from depression) may dependably arrive with spring. For many others, winter darkness simply means more blue moods. When asked “Have you cried today?” Americans have agreed more often in the winter (TABLE 15.6).

Table 15.6

Table 15.6Percentage Answering Yes When Asked “Have You Cried Today?”

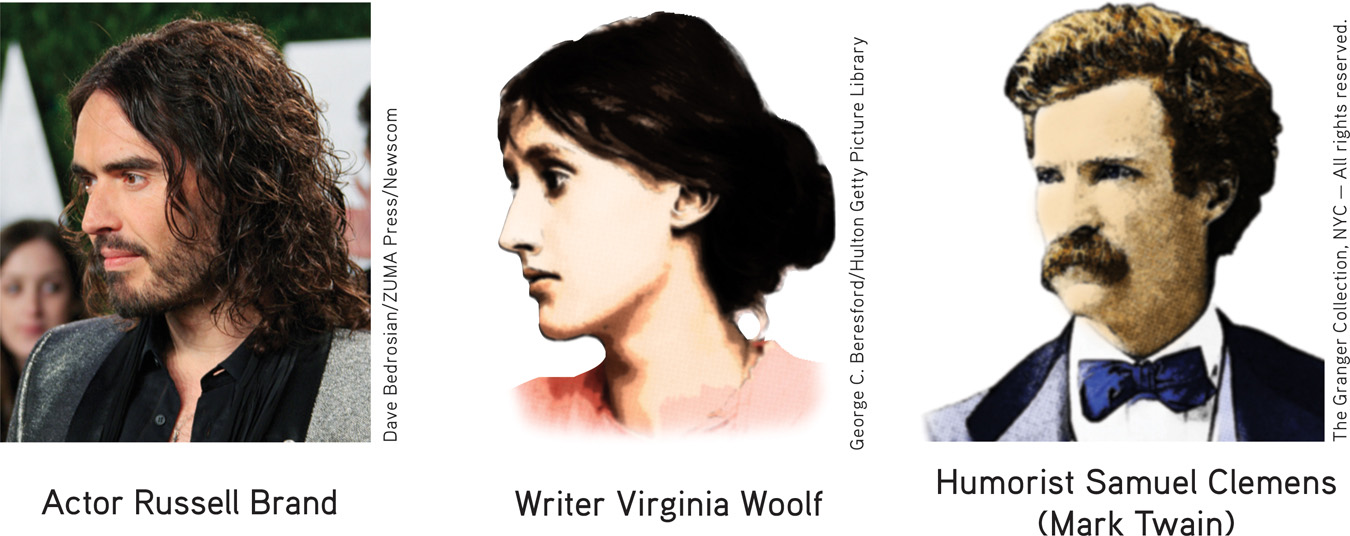

In milder forms, mania’s energy and flood of ideas fuel creativity. George Frideric Handel, who may have suffered from a mild form of bipolar disorder, composed his nearly four-

It is as true of emotions as of everything else: What goes up comes down. Before long, the elated mood either returns to normal or plunges into a depression. Though bipolar disorder is much less common than major depressive disorder, it is often more dysfunctional, claiming twice as many lost workdays yearly (Kessler et al., 2006). It afflicts adult men and women about equally.

631

Understanding Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorder

15-

In thousands of studies, psychologists continue to accumulate evidence to help explain why people have depressive disorders and bipolar disorder and to design more effective ways to treat and prevent them. Here, we focus primarily on depressive disorders. One research group summarized the facts that any theory of depression must explain, including the following (Lewinsohn et al., 1985, 1998, 2003):

- Many behavioral and cognitive changes accompany depression. People trapped in a depressed mood become inactive and feel unmotivated. They are sensitive to negative events (Peckham et al., 2010). They more often recall negative information. They expect negative outcomes (my team will lose, my grades will fall, my love will fail). When the depression lifts, these behavioral and cognitive accompaniments disappear. Nearly half the time, people also exhibit symptoms of another disorder, such as anxiety or substance abuse.

- Depression is widespread. Worldwide, more than 350 million people suffer depression (WHO, 2012). Although phobias are more common, depression is the number-one reason people seek mental health services. At some point during their lifetime, depression plagues 12 percent of Canadian adults and 17 percent of U.S. adults (Holden, 2010; Patten et al., 2006). Moreover, depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide (Ferrari et al., 2013). Depression’s commonality suggests that its causes, too, must be common.

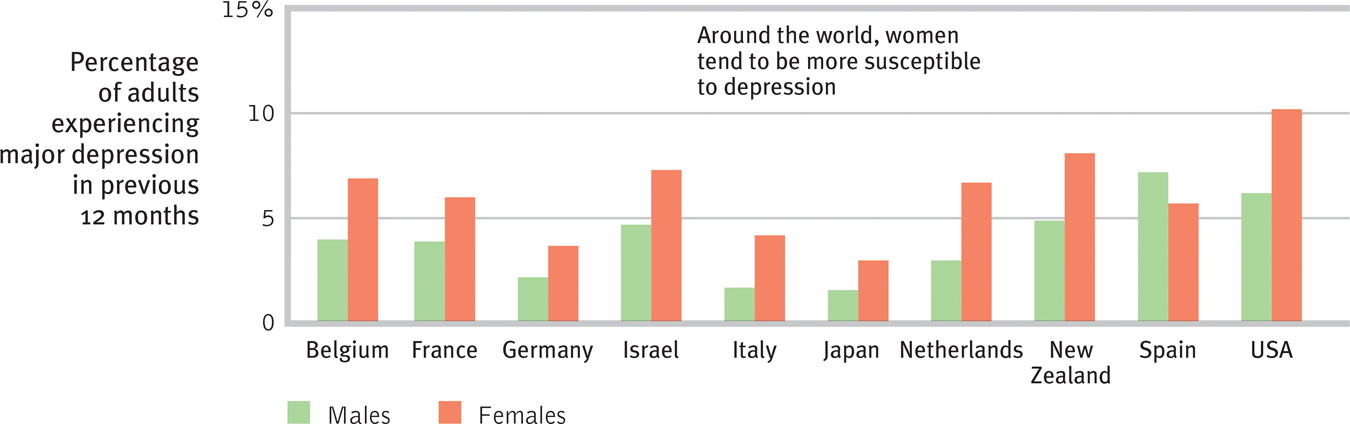

- Women’s risk of major depression is nearly double men’s. In 2009, when Gallup pollsters asked more than a quarter-million Americans if they had ever been diagnosed with depression, 13 percent of men and 22 percent of women said they had (Pelham, 2009). When Gallup asked Americans if they had experienced sadness “during a lot of the day yesterday,” 17 percent of men and 28 percent of women answered Yes (Mendes & McGeeney, 2012). The depression gender gap has been found worldwide (FIGURE 15.5). The trend begins in adolescence; preadolescent girls are not more depression-

prone than are boys (Hyde et al., 2008). With adolescence, girls often think and fret more about their bodies.

Figure 15.5

Figure 15.5

Gender and major depression Interviews with 89,037 adults in 18 countries (10 of which are shown here) confirm what many smaller studies have found: Women’s risk of major depression is nearly double that of men’s. (Data from Bromet et al., 2011.)The factors that put women at risk for depression (genetic predispositions, child abuse, low self-

esteem, marital problems, and so forth) similarly put men at risk (Kendler et al., 2006). Yet women are more vulnerable to disorders involving internalized states, such as depression, anxiety, and inhibited sexual desire. Women experience more situations that may increase their risk for depression, such as receiving less pay for equal work, juggling multiple roles, and caring for children and elderly family members (Freeman & Freeman, 2013). Men’s disorders tend to be more external— alcohol use disorder, antisocial conduct, lack of impulse control. When women get sad, they often get sadder than men do. When men get mad, they often get madder than women do. - Most major depressive episodes self-terminate. Therapy often helps and tends to speed recovery. But even without professional help, most people recover from major depression and return to normal. The plague of depression comes and, a few weeks or months later, it goes, though for some (about half), it eventually returns (Burcusa & Iacono, 2007; Curry et al., 2011; Hardeveld et al., 2010). Only about 20 percent experience chronic depression (Klein, 2010). On average, a person with major depressive disorder today will spend about three-fourths of the next decade in a normal, nondepressed state (Furukawa et al., 2009). Recovery is more likely to be permanent the later the first episode strikes, the longer the person stays well, the fewer the previous episodes, the less stress experienced, and the more social support received (Belsher & Costello, 1988; Fergusson & Woodward, 2002; Kendler et al., 2001).

- Stressful events related to work, marriage, and close relationships often precede depression. As anxiety is a response to the threat of future loss, depression is often a response to past and current loss. About 1 person in 4 diagnosed with depression has been brought down by a significant loss or trauma, such as a loved one’s death, a ruptured marriage, a physical assault, or a lost job (Kendler et al., 2008; Monroe & Reid, 2009; Orth et al., 2009; Wakefield et al., 2007). Minor daily stressors can also leave emotional scars. People who overreacted to minor stressors, such as a broken appliance, were more often depressed 10 years later (Charles et al., 2013). Moving to a new culture can also increase depression, especially among younger people who have not yet formed their identities (Zhang et al., 2013). One long-term study (Kendler, 1998) tracked rates of depression in 2000 people. The risk of depression ranged from less than 1 percent among those who had experienced no stressful life event in the preceding month to 24 percent among those who had experienced three such events in that month.

- With each new generation, depression strikes earlier (now often in the late teens) and affects more people, with the highest rates in developed countries among young adults. This trend has been reported in Canada, the United States, England, France, Germany, Italy, Lebanon, New Zealand, Puerto Rico, and Taiwan (Collishaw et al., 2007; Cross-National Collaborative Group, 1992; Kessler et al., 2010; Twenge et al., 2008). In one study, 12 percent of Australian adolescents reported symptoms of depression (Sawyer et al., 2000). Most hid it from their parents; almost 90 percent of those parents perceived their depressed teen as not suffering depression. In North America, young adults are three times more likely than their grandparents to report having recently—or ever—suffered depression (despite the grandparents’ many more years of being at risk). The increase appears partly authentic, but it may also reflect today’s young adults’ greater willingness to disclose depression.

632

“I see depression as the plague of the modern era.”

Lewis Judd, former chief, National Institute of Mental Health, 2000

Armed with these points of understanding, today’s researchers propose biological and cognitive explanations of depression, often combined in a biopsychosocial perspective.

The Biological Perspective

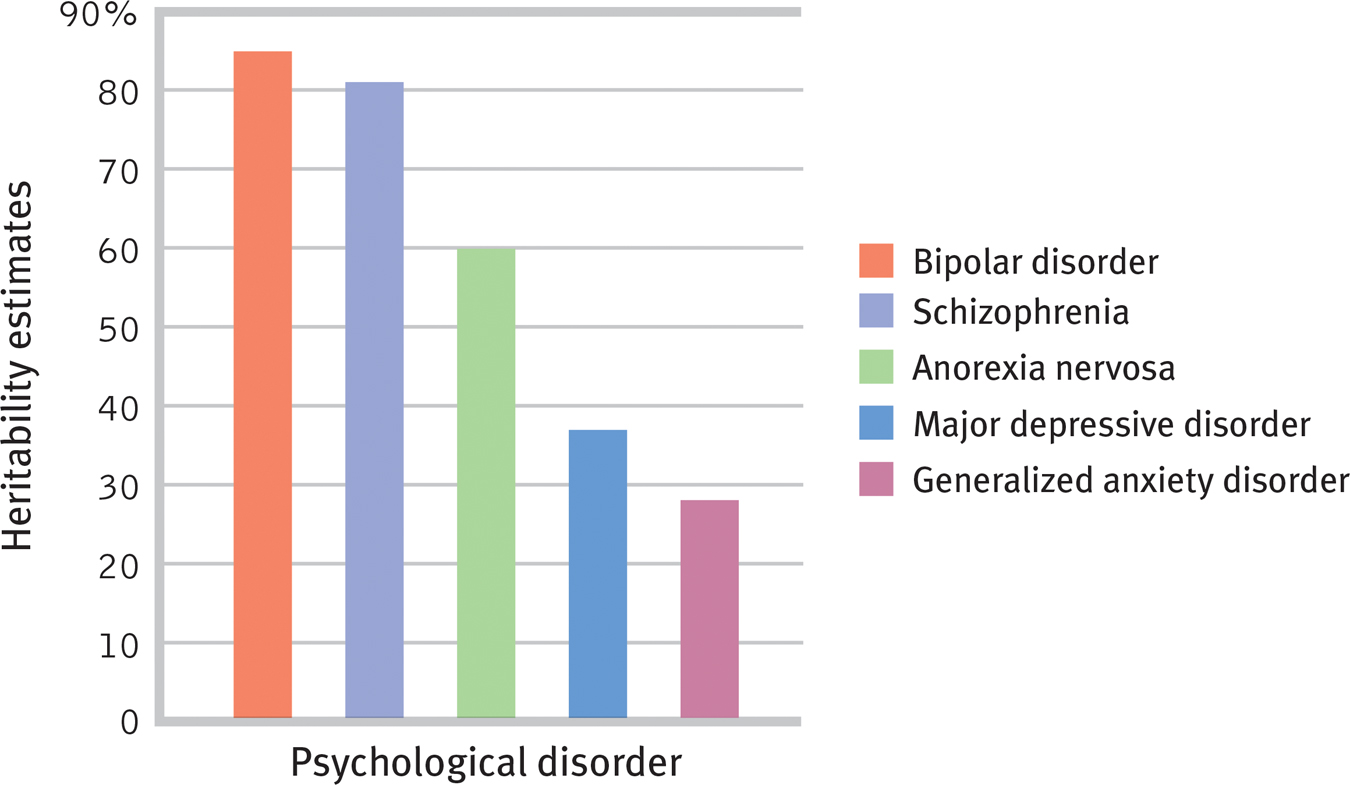

Genetic Influences Depressive disorders and bipolar disorder run in families. As one researcher noted, emotions are “postcards from our genes” (Plotkin, 1994). The risk of major depression and bipolar disorder increases if you have a parent or sibling with the disorder (Sullivan et al., 2000). If one identical twin is diagnosed with major depressive disorder, the chances are about 1 in 2 that at some time the other twin will be, too. This effect is even stronger for bipolar disorder: If one identical twin has it, the chances are 7 in 10 that the other twin will at some point be diagnosed similarly—

Figure 15.6

Figure 15.6The heritability of various psychological disorders Researchers Joseph Bienvenu, Dimitry Davydow, and Kenneth Kendler (2011) aggregated data from studies of identical and fraternal twins to estimate the heritability of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anorexia nervosa, major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.

633

To tease out the genes that put people at risk for depression, some researchers have turned to linkage analysis. First, geneticists find families in which the disorder appears across several generations. Next, the researchers examine DNA from affected and unaffected family members, looking for differences. Linkage analysis points them to a chromosome neighborhood; “A house-

The Depressed Brain Scanning devices open a window on the brain’s activity during depressed and manic states. One study gave 13 elite Canadian swimmers the wrenching experience of watching a video of the swim in which they failed to make the Olympic team or failed at the Olympic games (Davis et al., 2008). Functional MRI scans showed the disappointed swimmers experiencing brain activity patterns similar to those of patients with depressed moods.

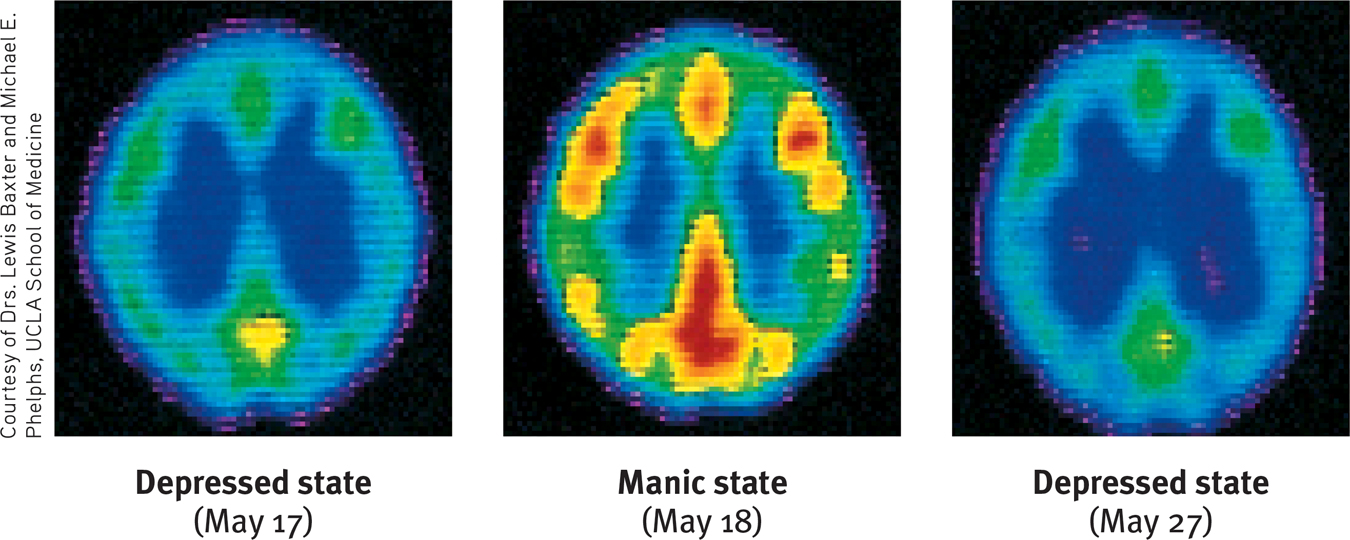

Many studies have found diminished brain activity during slowed-

Figure 15.7

Figure 15.7The ups and downs of bipolar disorder These top-

Neuroscientists have also discovered altered brain structures in people with bipolar disorder. One analysis discovered decreased white matter and enlarged fluid-

634

Neurotransmitter systems also influence depressive disorders and bipolar disorder. Norepinephrine, which increases arousal and boosts mood, is scarce during depression and overabundant during mania. (Drugs that decrease mania reduce norepinephrine.) Many people with a history of depression also have a history of habitual smoking (Pasco et al., 2008). Once the urge to smoke is ignited, depression also makes it more difficult to quit (Hitsman et al., 2012). This may indicate an attempt to self-

Researchers are also exploring a second neurotransmitter, serotonin (Carver et al., 2008). One well-

Drugs that relieve depression tend to increase norepinephrine or serotonin supplies by blocking either their reuptake (as Prozac, Zoloft, and Paxil do with serotonin) or their chemical breakdown. Repetitive physical exercise, such as jogging, reduces depression because it increases serotonin, which affects mood and arousal (Airan et al., 2007; Ilardi, 2009; Jacobs, 1994). In one study, running for two hours increased brain activation in regions associated with euphoria (Boecker et al., 2008). To run away from a bad mood, you can use your own two feet.

Nutritional Effects What’s good for the heart is also good for the brain and mind. People who eat a heart-

The Social-

Biological influences contribute to depression, but in the nature–

Thinking matters, too. The social-

I [despaired] of ever being human again. I honestly felt subhuman, lower than the lowest vermin. Furthermore, I was self-

Expecting the worst, depressed people’s self-

rumination compulsive fretting; overthinking about our problems and their causes.

635

Negative Thoughts and Negative Moods Interact Self-

Even so, why do life’s unavoidable failures lead only some people to become depressed? The answer lies partly in their explanatory style—who or what they blame for their failures. Think of how you might feel if you failed a test. If you can externalize the blame (“What an unfair test!”), you are more likely to feel angry. If you blame yourself, you probably will feel stupid and depressed.

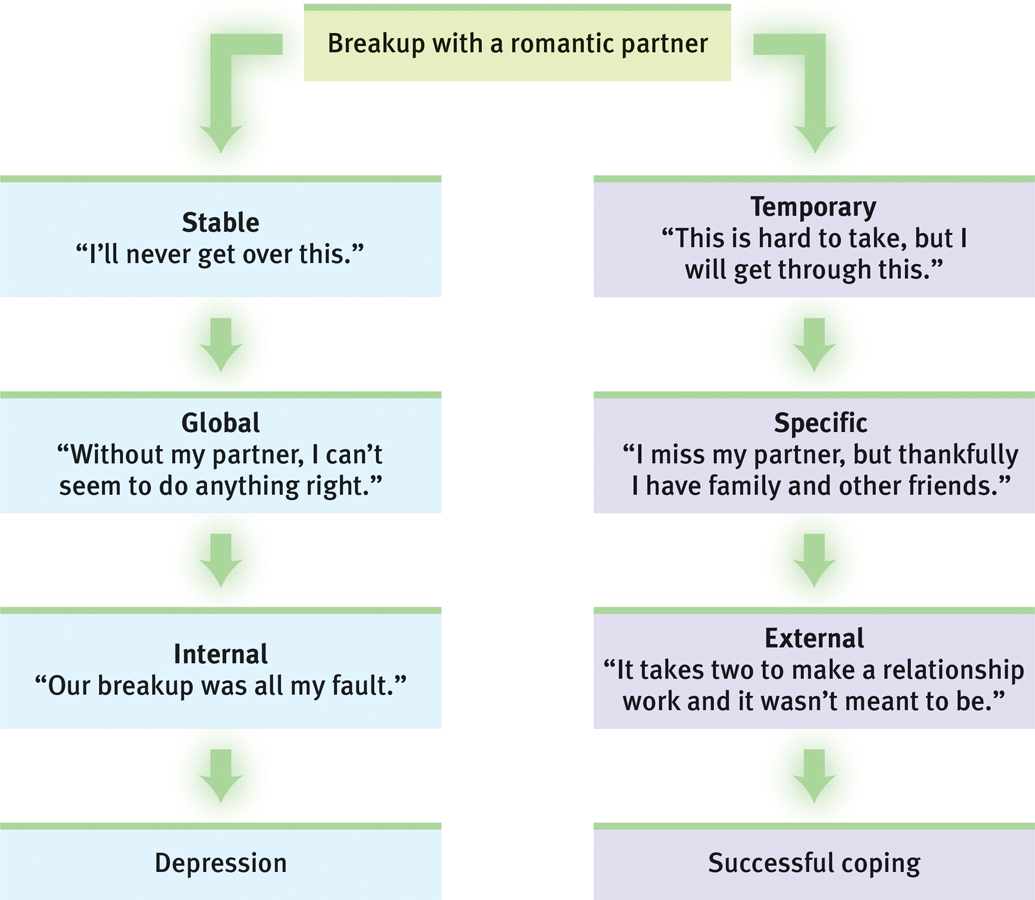

So it is with depressed people, who often explain bad events in terms that are stable (“It’s going to last forever”), global (“It’s going to affect everything I do”), and internal (“It’s all my fault”) (FIGURE 15.8). Depression-

Figure 15.8

Figure 15.8Explanatory style and depression After a negative experience, a depression-

Pessimistic, overgeneralized, self-

636

Why is depression so common among young Westerners? Seligman (1991, 1995) has pointed to the rise of individualism and the decline of commitment to religion and family, which forces young people to take responsibility for failure or rejection. In non-

Critics note a chicken-

“Man never reasons so much and becomes so introspective as when he suffers, since he is anxious to get at the cause of his sufferings.”

Luigi Pirandello, Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1922

Depression’s Vicious Cycle Depression is both a cause and an effect of stressful experiences that disrupt our sense of who we are and why we are worthy human beings. Such disruptions can lead to brooding, which amplifies negative feelings. Being withdrawn, self-

“Some cause happiness wherever they go; others, whenever they go.”

Irish writer Oscar Wilde (1854–1900)

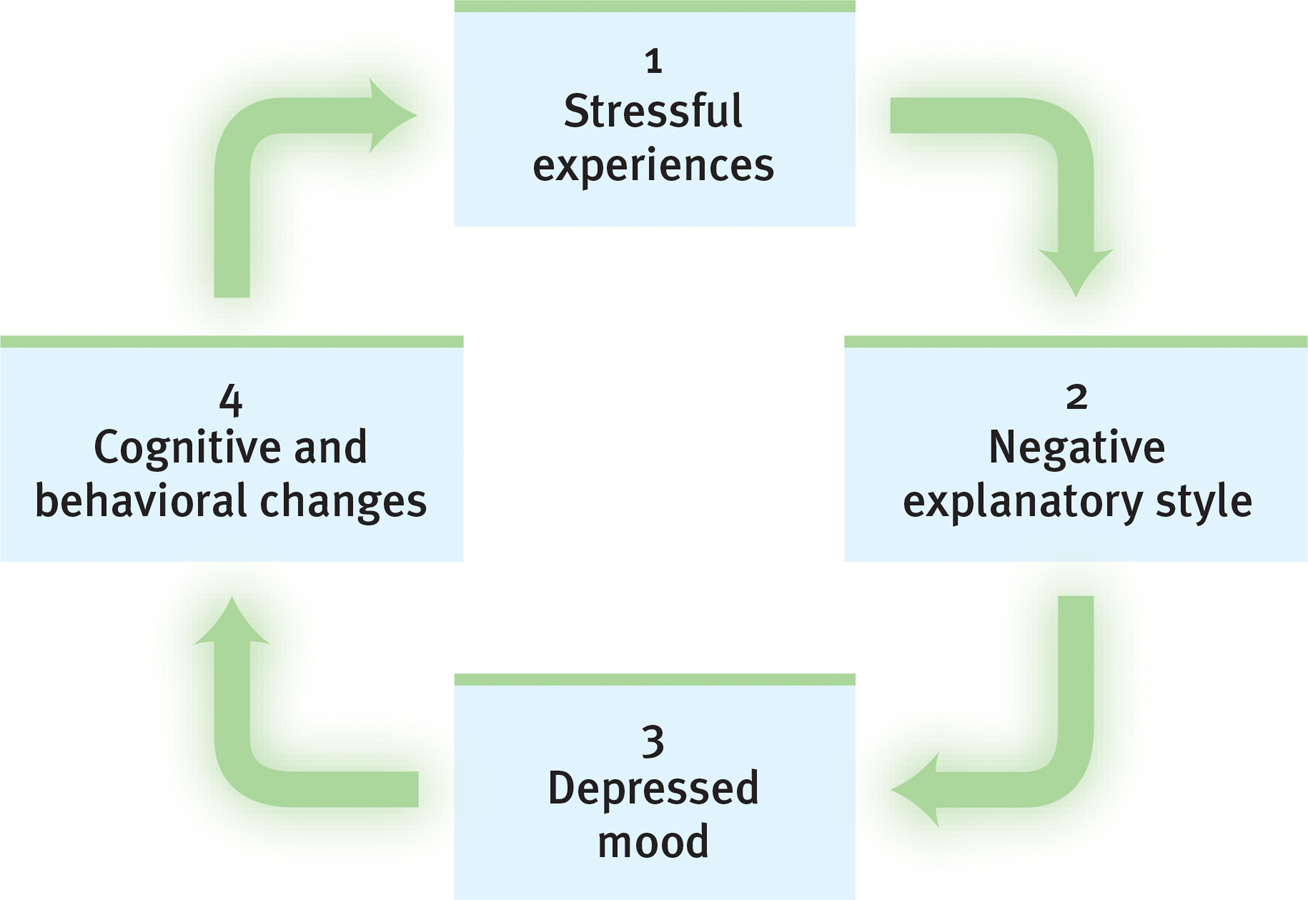

We can now assemble some of the pieces of the depression puzzle (FIGURE 15.9): (1) Negative, stressful events interpreted through (2) a ruminating, pessimistic explanatory style create (3) a hopeless, depressed state that (4) hampers the way the person thinks and acts. This, in turn, fuels (1) negative, stressful experiences such as rejection. Depression is a snake that bites its own tail.

Figure 15.9

Figure 15.9The vicious cycle of depressed thinking Therapists recognize this cycle, and they work to help depressed people break out of it. Each of the bottom three points offers an exit to work toward: 2. Reverse self-

None of us are immune to the dejection, diminished self-

637

It is a cycle we can all recognize. Bad moods feed on themselves: When we feel down, we think negatively and remember bad experiences. Abraham Lincoln was so withdrawn and brooding as a young man that his friends feared he might take his own life (Kline, 1974). Poet Emily Dickinson was so afraid of bursting into tears in public that she spent much of her adult life in seclusion (Patterson, 1951). As their lives remind us, people can and do struggle through depression. Most regain their capacity to love, to work, and even to succeed at the highest levels.

Suicide and Self-

15-

“But life, being weary of these worldly bars, Never lacks power to dismiss itself.”

William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, 1599

Each year over 800,000 despairing people worldwide will elect a permanent solution to what might have been a temporary problem (WHO, 2014). For those who have been depressed, the risk of suicide is at least five times greater than for the general population (Bostwick & Pankratz, 2000). People seldom commit suicide while in the depths of depression, when energy and initiative are lacking. The risk increases when they begin to rebound and become capable of following through.

Comparing the suicide rates of different groups, researchers have found

- national differences: Britain’s, Italy’s, and Spain’s suicide rates are little more than half those of Canada, Australia, and the United States. Austria’s and Finland’s are about double (WHO, 2011). Within Europe, people in the most suicide-prone country (Belarus) have been 16 times more likely to kill themselves than those in the least (Georgia).

- racial differences: Within the United States, Whites and Native Americans kill themselves twice as often as Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians (CDC, 2012).

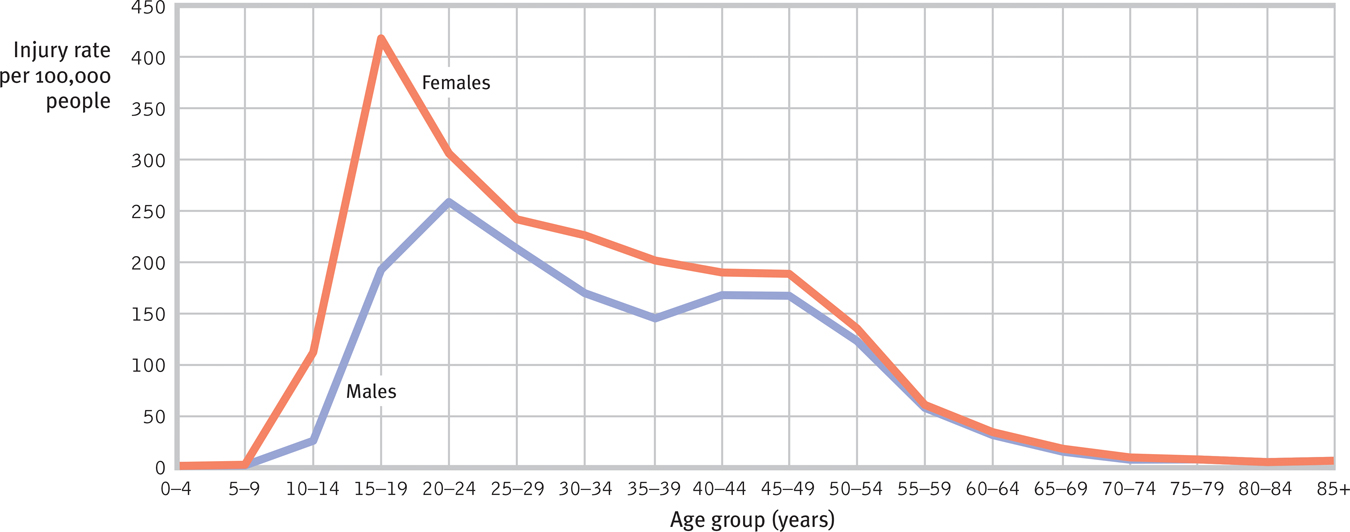

- gender differences: Women are much more likely than men to attempt suicide (WHO, 2011). But men are two to four times more likely (depending on the country) to actually end their lives. Men use more lethal methods, such as firing a bullet into the head, the method of choice in 6 of 10 U.S. suicides.

- age differences and trends: In late adulthood, rates increase, peaking in middle age and beyond. In the last half of the twentieth century, the global rate of annual suicide deaths nearly doubled (WHO, 2008).

- other group differences: Suicide rates have been much higher among the rich, the nonreligious, and those who were single, widowed, or divorced (Hoyer & Lund, 1993; Okada & Samreth, 2013; Stack, 1992; Stengel, 1981). Witnessing physical pain and trauma can increase the risk of suicide, which may help explain physicians’ elevated suicide rates (Bender et al., 2012; Cornette et al., 2009). Gay and lesbian youth facing an unsupportive environment, including family or peer rejection, are also at increased risk of attempting suicide (Goldfried, 2001; Haas et al., 2011; Hatzenbuehler, 2011). Among people with alcohol use disorder, 3 percent die by suicide. This rate is roughly 100 times greater than the rate for people without alcohol use disorder (Murphy & Wetzel, 1990; Sher, 2006).

- day of the week differences: Negative emotion tends to go up midweek, which can have tragic consequences (Watson, 2000). A surprising 25 percent of U.S. suicides occur on Wednesdays (Kposowa & D’Auria, 2009).

638

Social suggestion may trigger suicide. Following highly publicized suicides and TV programs featuring suicide, known suicides increase. So do fatal auto and private airplane “accidents.” One six-

Because suicide is so often an impulsive act, environmental barriers (such as jump barriers on high bridges and the unavailability of loaded guns) can save lives (Anderson, 2008). Common sense may suggest that a determined person will simply find another way to complete the act, but such restrictions give time for self-

Suicide is not necessarily an act of hostility or revenge. People—

In hindsight, families and friends may recall signs they believe should have forewarned them—

Nonsuicidal Self-

- find relief from intense negative thoughts through the distraction of pain.

- attract attention and possibly get help.

- relieve guilt by inflicting self-punishment.

- get others to change their negative behavior (bullying, criticism).

- fit in with a peer group.

Figure 15.10

Figure 15.10Rates of nonfatal self-

639

Does NSSI lead to suicide? Usually not. Those who engage in NSSI are typically suicide gesturers, not suicide attempters (Nock & Kessler, 2006). Suicide gesturers engage in NSSI as a desperate but non-

“People desire death when two fundamental needs are frustrated to the point of extinction: The need to belong with or connect to others, and the need to feel effective with or to influence others.”

Thomas Joiner (2006, p. 47)

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What does it mean to say that “depression is a whole-body disorder”?

Many factors contribute to depression, including the biological influences of genetics and brain function. Social-

REVIEW: Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorder

|

REVIEW | Depressive Disorders and Bipolar Disorder |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

15-

A person with major depressive disorder experiences two or more weeks with five or more symptoms, at least one of which must be either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. Persistent depressive disorder includes a mildly depressed mood more often than not for at least two years, along with at least two other symptoms. A person with the less common condition of bipolar disorder experiences not only depression but also mania—episodes of hyperactive and wildly optimistic, impulsive behavior.

15-

The biological perspective on depressive disorders and bipolar disorder focuses on genetic predispositions and on abnormalities in brain structures and function (including those found in neurotransmitter systems). The social-cognitive perspective views depression as an ongoing cycle of stressful experiences (interpreted through negative beliefs, attributions, and memories) leading to negative moods and actions and fueling new stressful experiences.

15-

Suicide rates differ by nation, race, gender, age group, income, religious involvement, marital status, and (for gay and lesbian youth, for example) social support structure. Those with depression are more at risk for suicide than others are, but social suggestion, health status, and economic and social frustration are also contributing factors. Environmental barriers (such as jump barriers) are effective in preventing suicides. Forewarnings of suicide may include verbal hints, giving away possessions, withdrawal, preoccupation with death, and discussing one’s own suicide.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) does not usually lead to suicide but may escalate to suicidal thoughts and acts if untreated. People who engage in NSSI do not tolerate stress well and tend to be self-critical, with poor communication and problem-solving skills.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

major depressive disorder mania bipolar disorder rumination | compulsive fretting; overthinking about our problems and their causes. a disorder in which a person experiences, in the absence of drugs or another medical condition, two or more weeks with five or more symptoms, at least one of which must be either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure. a hyperactive, wildly optimistic state in which dangerously poor judgment is common. a disorder in which a person alternates between the hopelessness and lethargy of depression and the overexcited state of mania. (Formerly called manic-depressive disorder.) |

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.

640