3.1 Brain States and Consciousness

Every science has concepts so fundamental they are nearly impossible to define. Biologists agree on what is alive but not on precisely what life is. In physics, matter and energy elude simple definition. To psychologists, consciousness is similarly a fundamental yet slippery concept.

Defining Consciousness

3-

“Psychology must discard all reference to consciousness.”

Behaviorist John B. Watson (1913)

At its beginning, psychology was “the description and explanation of states of consciousness” (Ladd, 1887). But during the first half of the twentieth century, the difficulty of scientifically studying consciousness led many psychologists—

For coverage of hypnosis, see the Chapter 6 discussion of pain. For more on meditation, see Chapter 12.

After 1960, mental concepts reemerged. Neuroscience advances linked brain activity to sleeping, dreaming, and other mental states. Researchers began studying consciousness altered by hypnosis, drugs, and meditation. Psychologists of all persuasions were affirming the importance of cognition, or mental processes. Psychology was regaining consciousness.

consciousness our awareness of ourselves and our environment.

Most psychologists now define consciousness as our awareness of ourselves and our environment. This awareness allows us to assemble information from many sources as we reflect on our past and plan for our future. And it focuses our attention when we learn a complex concept or behavior. When learning to drive, we focus on the car and the traffic. With practice, driving becomes semiautomatic, freeing us to focus our attention on other things. Over time, we flit between different states of consciousness, including normal waking awareness and various altered states (FIGURE 3.1).

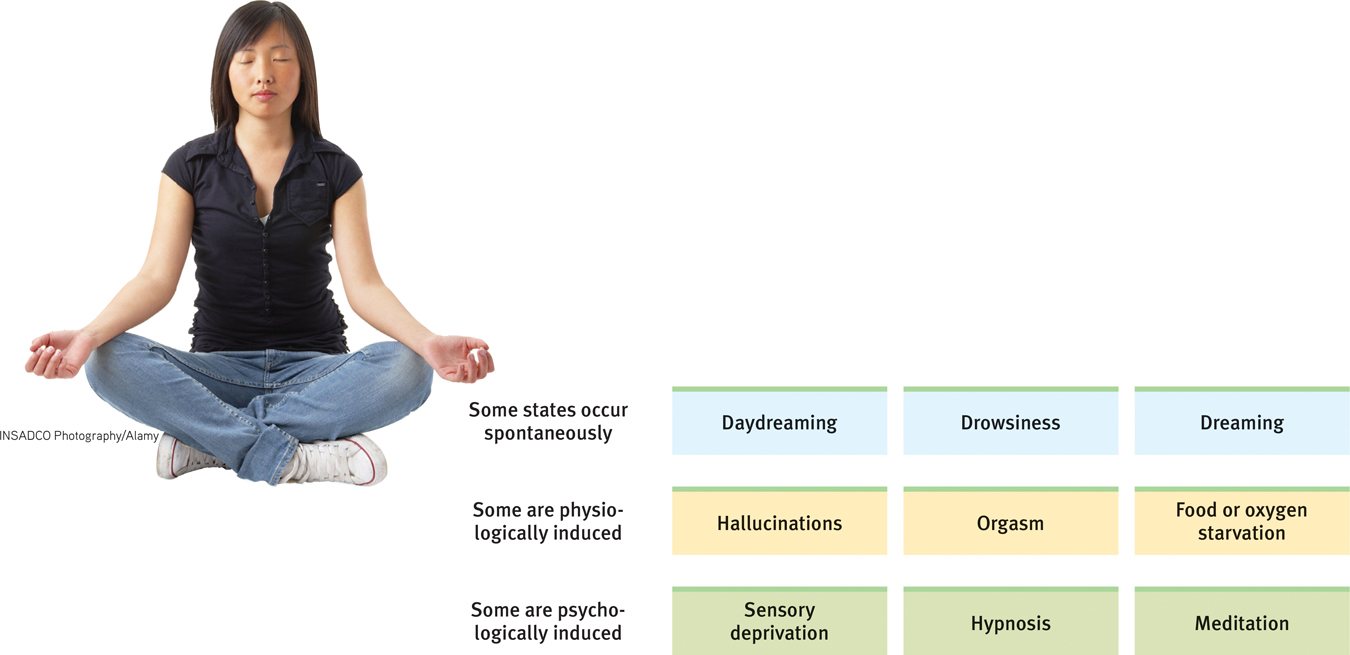

FIGURE 3.1

FIGURE 3.1Altered states of consciousness In addition to normal, waking awareness, consciousness comes to us in altered states, including daydreaming, drug-

Today’s science explores the biology of consciousness. Evolutionary psychologists presume that consciousness offers a reproductive advantage (Barash, 2006; Murdik et al., 2011). Consciousness helps us cope with novel situations and act in our long-

Such explanations still leave us with the “hard problem”: How do brain cells jabbering to one another create our awareness of the taste of a taco, the idea of infinity, the feeling of fright? The question of how consciousness arises from the material brain is, for many scientists, one of life’s deepest mysteries.

93

The Biology of Consciousness

3-

Cognitive Neuroscience

cognitive neuroscience the interdisciplinary study of the brain activity linked with cognition (including perception, thinking, memory, and language).

Scientists assume, in the words of neuroscientist Marvin Minsky (1986, p. 287), that “the mind is what the brain does.” We just don’t know how it does it. Even with all the world’s technology, we still don’t have a clue how to make a conscious robot. Yet today’s cognitive neuroscience—the interdisciplinary study of the brain activity linked with our mental processes—

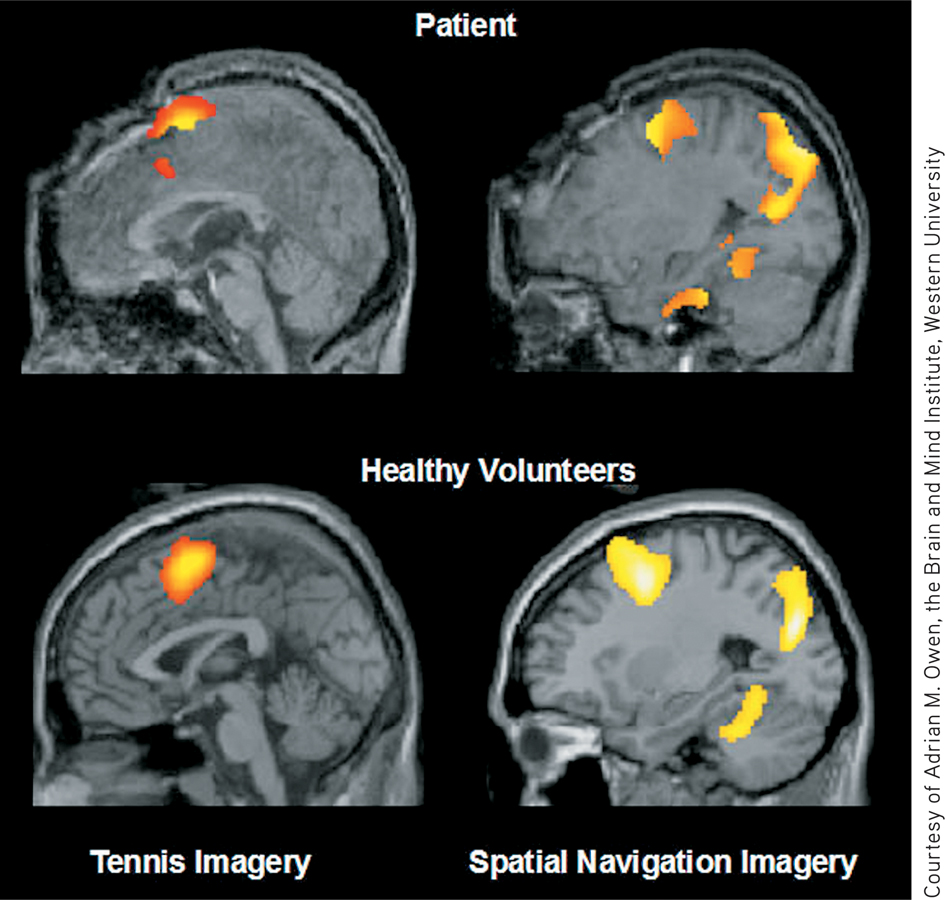

A stunning demonstration of consciousness appeared in brain scans of a noncommunicative patient—

FIGURE 3.2

FIGURE 3.2Evidence of awareness? When asked to imagine playing tennis or navigating her home, a vegetative patient’s brain (top) exhibited activity similar to a healthy person’s brain (bottom). Researchers wonder if such fMRI scans might enable a “conversation” with some unresponsive patients, by instructing them, for example, to answer yes to a question by imagining playing tennis (top and bottom left), and no by imagining walking around their home (top and bottom right).

Many cognitive neuroscientists are exploring and mapping the conscious functions of the cortex. Based on your cortical activation patterns, they can now, in limited ways, read your mind (Bor, 2010). They could, for example, tell which of 10 similar objects (hammer, drill, and so forth) you were viewing (Shinkareva et al., 2008).

Some neuroscientists believe that conscious experience arises from synchronized activity across the brain (Gaillard et al., 2009; Koch & Greenfield, 2007; Schurger et al., 2010). If a stimulus activates enough brain-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Those working in the interdisciplinary field called ______________ ______________ study the brain activity associated with perception, thinking, memory, and language.

cognitive neuroscience

Dual Processing: The Two-

Many cognitive neuroscience discoveries tell us of a particular brain region that becomes active with a particular conscious experience. Such findings strike many people as interesting but not mind blowing. (If everything psychological is simultaneously biological, then our ideas, emotions, and spirituality must all, somehow, be embodied.) What is mind blowing to many of us is the growing evidence that we have, so to speak, two minds, each supported by its own neural equipment.

dual processing the principle that information is often simultaneously processed on separate conscious and unconscious tracks.

At any moment, you and I are aware of little more than what’s on the screen of our consciousness. But beneath the surface, unconscious information processing occurs simultaneously on many parallel tracks. When we look at a bird flying, we are consciously aware of the result of our cognitive processing (“It’s a hummingbird!”) but not of our subprocessing of the bird’s color, form, movement, and distance. One of the grand ideas of recent cognitive neuroscience is that much of our brain work occurs off stage, out of sight. Perception, memory, thinking, language, and attitudes all operate on two levels—

94

If you are a driver, consider how you move to the right lane. Drivers know this unconsciously but cannot accurately explain it (Eagleman, 2011). Most say they would bank to the right, then straighten out—

blindsight a condition in which a person can respond to a visual stimulus without consciously experiencing it.

Or consider this story, which illustrates how science can be stranger than science fiction. During my sojourns at Scotland’s University of St. Andrews, I [DM] came to know cognitive neuroscientists David Milner and Melvyn Goodale (2008). A local woman, whom they call D.F., suffered brain damage when overcome by carbon monoxide, leaving her unable to recognize and discriminate objects visually. Consciously, D.F. could see nothing. Yet she exhibited blindsight—she acted as though she could see. Asked to slip a postcard into a vertical or horizontal mail slot, she could do so without error. Asked the width of a block in front of her, she was at a loss, but she could grasp it with just the right finger–

How could this be? Don’t we have one visual system? Goodale and Milner knew from animal research that the eye sends information simultaneously to different brain areas, which support different tasks (Weiskrantz, 2009, 2010). Sure enough, a scan of D.F.’s brain activity revealed normal activity in the area concerned with reaching for, grasping, and navigating objects, but damage in the area concerned with consciously recognizing objects.1 (See another example in FIGURE 3.3.)

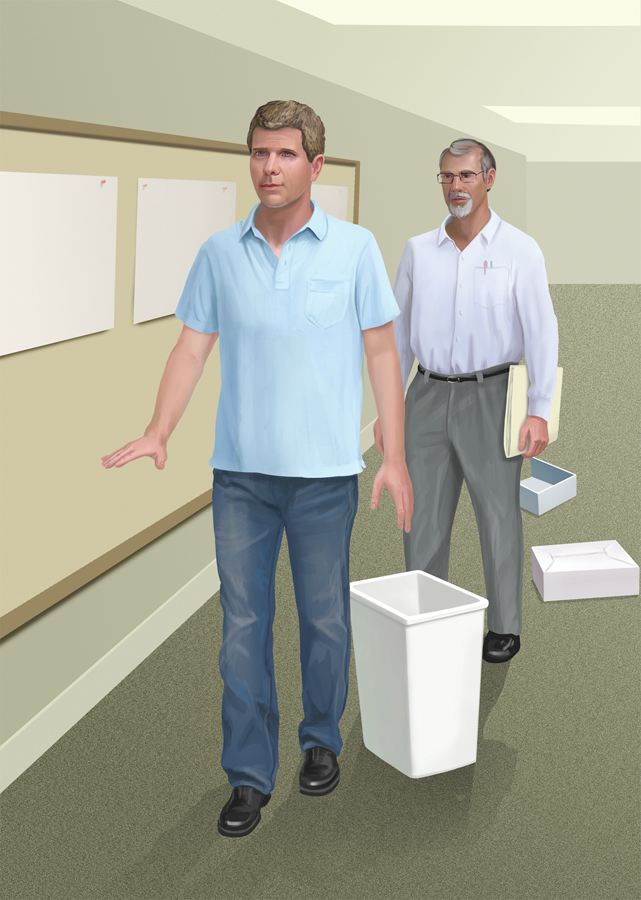

FIGURE 3.3

FIGURE 3.3When the blind can “see” In this compelling demonstration of blindsight and the two-

How strangely intricate is this thing we call vision, conclude Goodale and Milner in their aptly titled book, Sight Unseen. We may think of our vision as a single system that controls our visually guided actions. Actually, it is a dual-

The dual-

People often have trouble accepting that much of our everyday thinking, feeling, and acting operates outside our conscious awareness (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999). We are understandably biased to believe that our intentions and deliberate choices rule our lives. But consciousness, though enabling us to exert voluntary control and to communicate our mental states to others, is but the tip of the information-

95

Here’s another weird (and provocative) finding: Experiments show that when you move your wrist at will, you consciously experience the decision to move it about 0.2 seconds before the actual movement (Libet, 1985, 2004). No surprise there. But your brain waves jump about 0.35 seconds before you consciously perceive your decision to move (FIGURE 3.4)! The startling conclusion: Consciousness sometimes arrives late to the decision-

FIGURE 3.4

FIGURE 3.4Is the brain ahead of the mind? In this study, volunteers watched a computer clock sweep through a full revolution every 2.56 seconds. They noted the time at which they decided to move their wrist. About one-

That inference has triggered more research and much debate. Does our brain really make decisions before we know about them? If so, is free will an illusion? Using fMRI scans, EEG recordings, or implanted electrodes, some studies seem to confirm that brain activity precedes—

To think further about the implications of these provocative findings for our understanding of free will and decision making, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Who’s in Charge?

To think further about the implications of these provocative findings for our understanding of free will and decision making, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Who’s in Charge?

Running on automatic pilot allows our consciousness—

Great myths often engage simple pairs: good Cinderella and the evil stepmother, the slow Tortoise and fast Hare, the logical Sherlock Holmes and emotional Dr. Watson. The myths have enduring power because they express our human reality. Dualities are us.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are the mind’s two tracks, and what is “dual processing”?

Our mind has separate conscious and unconscious tracks that perform dual processing—

Selective Attention

3-

parallel processing the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions.

Unconscious parallel processing is faster than sequential conscious processing, but both are essential. Parallel processing enables your mind to take care of routine business. Sequential processing is best for solving new problems, which requires our focused attention. Try this: If you are right-

96

selective attention the focusing of conscious awareness on a particular stimulus.

Through selective attention, your awareness focuses, like a flashlight beam, on a minute aspect of all that you experience. By one estimate, your five senses take in 11,000,000 bits of information per second, of which you consciously process about 40 (Wilson, 2002). Yet your mind’s unconscious track intuitively makes great use of the other 10,999,960 bits. Until reading this sentence, for example, you have been unaware of the chair pressing against your bottom or that your nose is in your line of vision. Now, suddenly, your attentional spotlight shifts. Your feel the chair, your nose stubbornly intrudes on the words before you. While focusing on these words, you’ve also been blocking other parts of your environment from awareness, though your peripheral vision would let you see them easily. You can change that. As you stare at the X below, notice what surrounds these sentences.

X

A classic example of selective attention is the cocktail party effect—your ability to attend to only one voice among many. Let another voice speak your name and your cognitive radar, operating on your mind’s other track, will instantly bring that unattended voice into consciousness. This effect might have prevented an embarrassing and dangerous situation in 2009, when two Northwest Airlines pilots “lost track of time.” Focused on their laptops and in conversation, they ignored alarmed air traffic controllers’ attempts to reach them and overflew their Minneapolis destination by 150 miles. If only the controllers had known and spoken the pilots’ names.

Selective Attention and Accidents

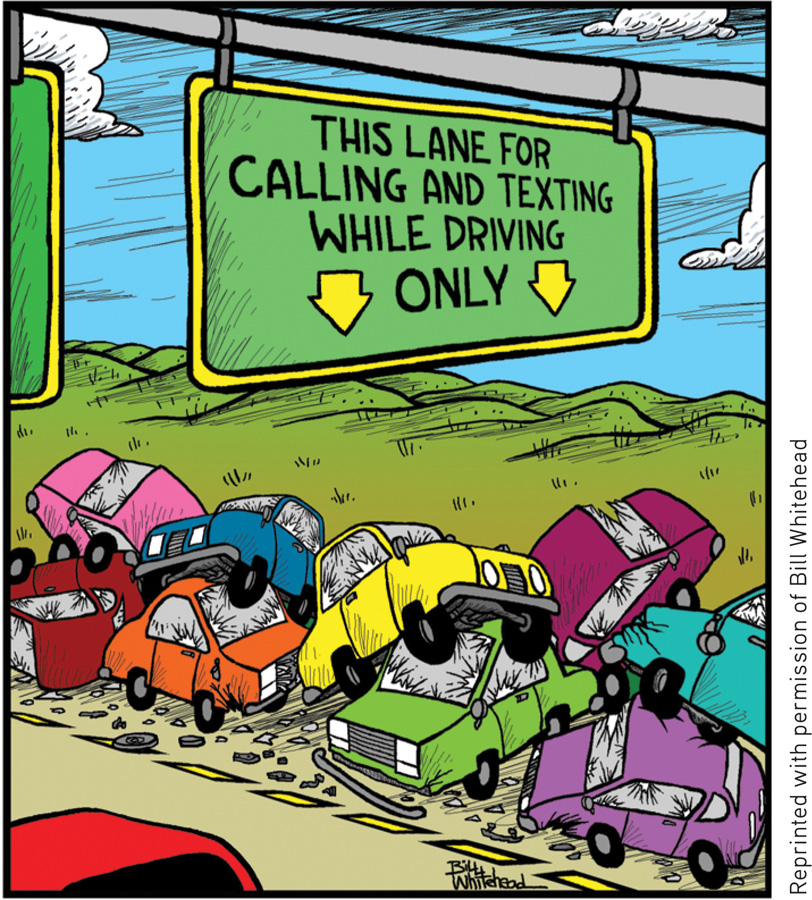

Talk or text while driving, or attend to music selection or route planning, and your selective attention will shift back and forth between the road and its electronic competition. Indeed, it shifts more often than we realize. One study left people in a room free to surf the Internet and to control and watch a TV. On average, they guessed their attention switched 14.8 times during the 27.5 minute session. But they were not even close. Eye-

We pay a toll for switching attentional gears, especially when we shift to complex tasks, like noticing and avoiding cars around us. The toll is a slight and sometimes fatal delay in coping (Rubenstein et al., 2001). About 28 percent of traffic accidents occur when people are chatting or texting on cell phones (National Safety Council, 2010). One study tracked long-

It’s not just truck drivers who are at risk. One in four drivers admit to texting while driving (Pew, 2011). Multitasking comes at a cost: fMRI scans offer a biological account of how multitasking distracts from brain resources allocated to driving. In areas vital to driving, brain activity decreases an average 37 percent when a driver is attending to conversation (Just et al., 2008). To demonstrate the impossibility of simultaneous multitasking, try mentally multiplying 18 × 42 while passing a truck in busy traffic. (Actually, don’t try this.)

Visit LaunchPad to watch the thought-provoking Video—Automatic Skills: Disrupting a Pilot’s Performance.

Visit LaunchPad to watch the thought-provoking Video—Automatic Skills: Disrupting a Pilot’s Performance.

Even hands-

97

- University of Sydney researchers analyzed phone records for the moments before a car crash. Cell-phone users (even those with hands-free sets) were, like the average drunk driver, four times more at risk (McEvoy et al., 2005, 2007). Having a passenger increased risk only 1.6 times.

Driven to distraction In driving-simulation experiments, people whose attention is diverted by texting and cell-phone conversation make more driving errors.

Driven to distraction In driving-simulation experiments, people whose attention is diverted by texting and cell-phone conversation make more driving errors. - When another research team installed cameras, GPS systems, and various sensors to the cars of teen drivers, they found that crashes and near-crashes increased sevenfold when dialing or reaching for a phone, and fourfold when sending or receiving a text message (Klauer et al., 2014).

- This risk difference also appeared when drivers were asked to pull off at a freeway rest stop 8 miles ahead. Of drivers conversing with a passenger, 88 percent did so. Of those talking on a cell phone, 50 percent drove on by (Strayer & Drews, 2007). And the increased risks are equal for handheld and hands-free phones, indicating that the distraction effect is mostly cognitive rather than visual (Strayer & Watson, 2012).

Most European countries and some American states now ban hand-

Selective Inattention

inattentional blindness failing to see visible objects when our attention is directed elsewhere.

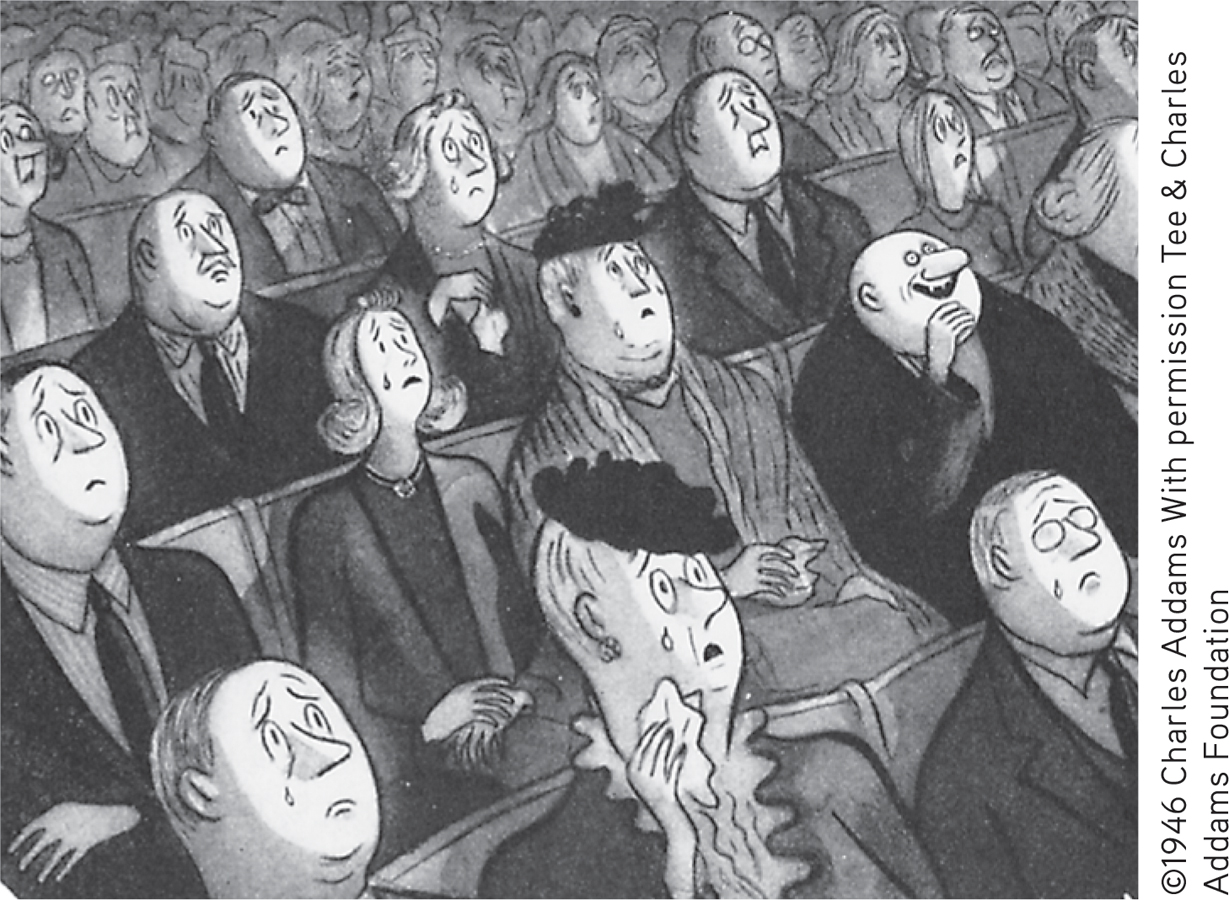

At the level of conscious awareness, we are “blind” to all but a tiny sliver of visual stimuli. Ulric Neisser (1979) and Robert Becklen and Daniel Cervone (1983) demonstrated this inattentional blindness dramatically by showing people a one-

FIGURE 3.5

FIGURE 3.5Selective inattention Viewers who were attending to basketball tosses among the black-

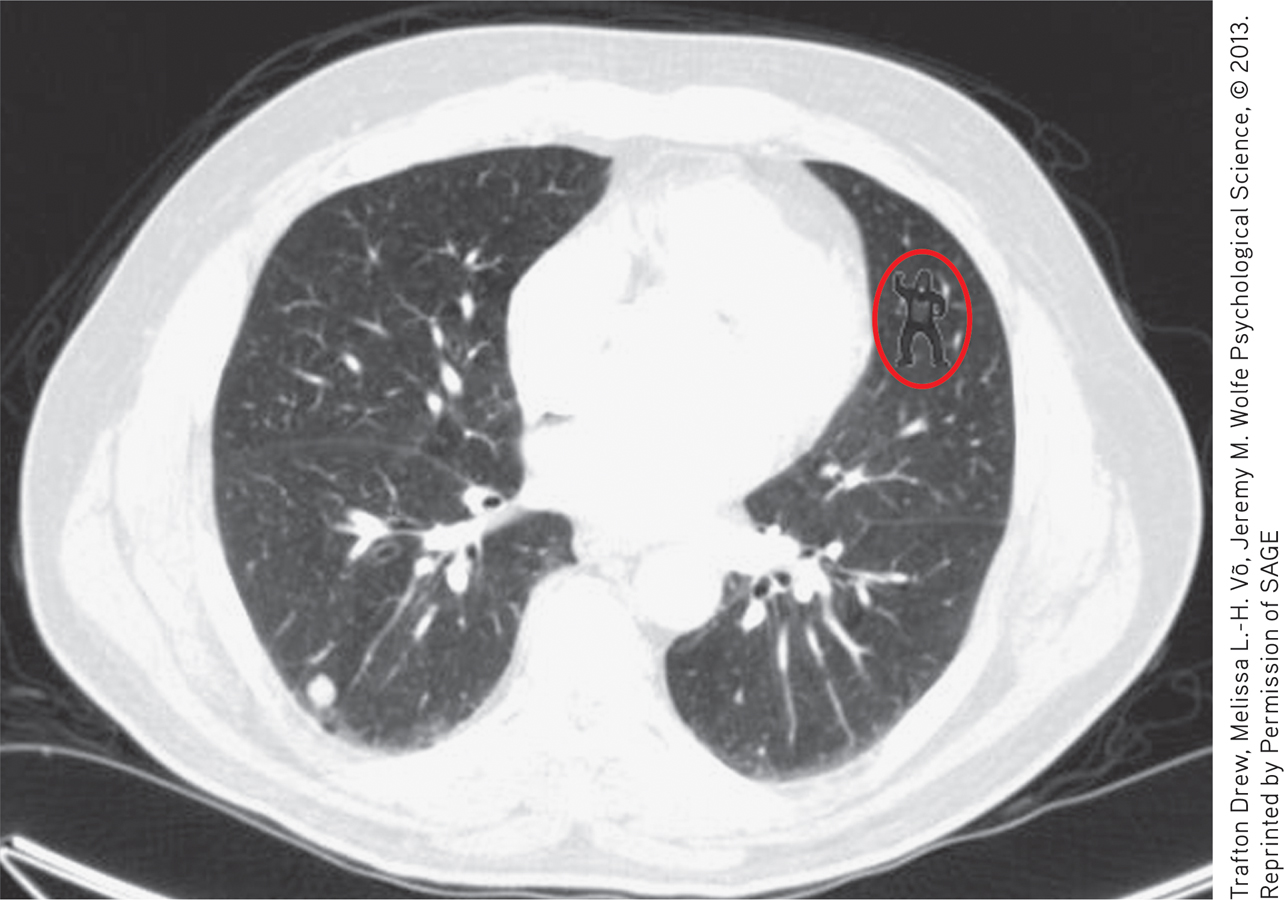

In a repeat of the experiment, smart-

FIGURE 3.6

FIGURE 3.6The invisible gorilla strikes again When exposed to the gorilla in the upper right several times, and even when looking at it, radiologists, searching for much tinier cancer nodules, usually failed to see it (Drew et al., 2013).

98

Given that most people miss someone in a gorilla suit while their attention is riveted elsewhere, imagine the fun that magicians can have by manipulating our selective attention. Misdirect people’s attention and they will miss the hand slipping into the pocket. “Every time you perform a magic trick, you’re engaging in experimental psychology,” says magician Teller, a master of mind-

“Has a generation of texters, surfers, and twitterers evolved the enviable ability to process multiple streams of novel information in parallel? Most cognitive psychologists doubt it.”

Steven Pinker, “Not at All,” 2010

change blindness failing to notice changes in the environment.

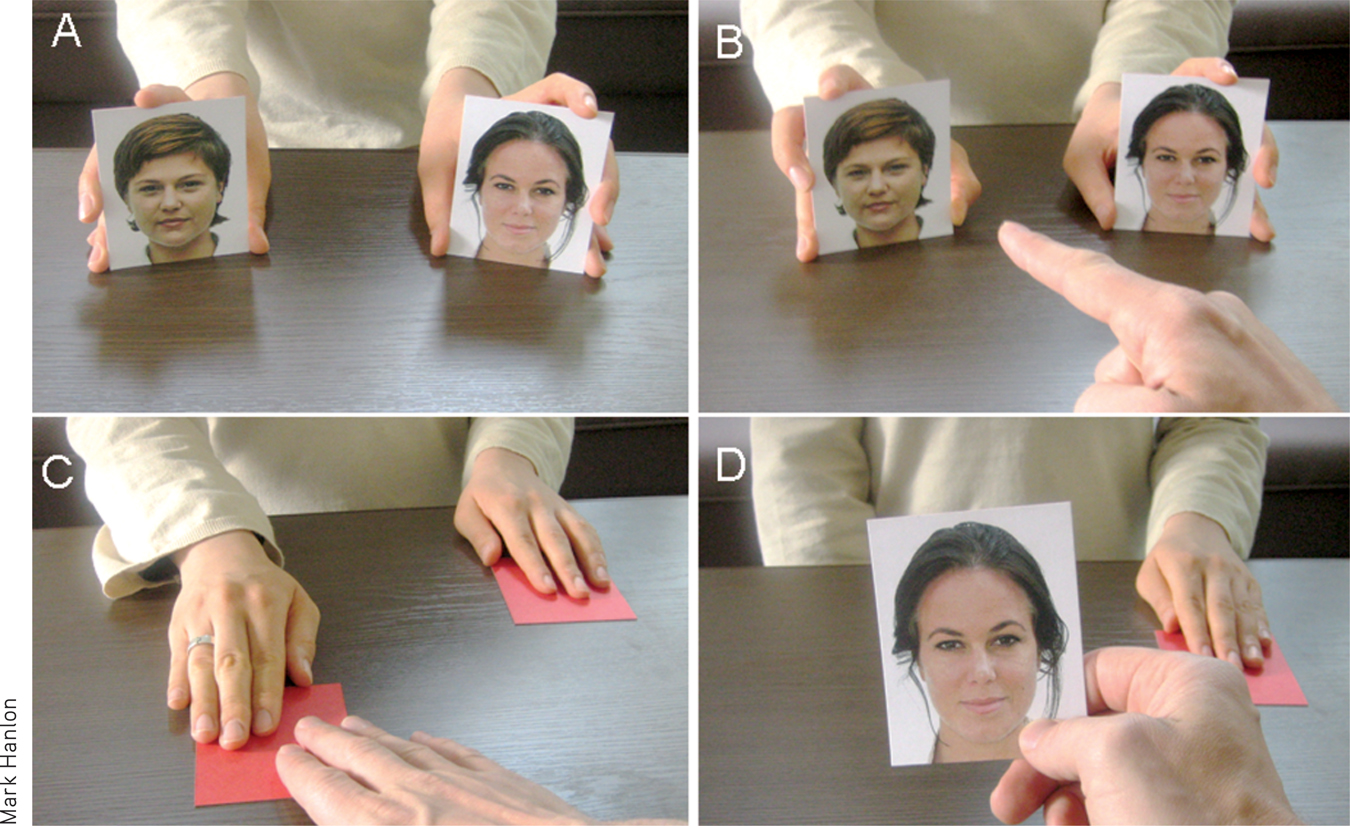

In other experiments, people exhibited a form of inattentional blindness called change blindness. In laboratory experiments, viewers didn’t notice that, after a brief visual interruption, a big Coke bottle had disappeared, a railing had risen, or clothing color had changed (Chabris & Simons, 2010; Resnick et al., 1997). Focused on giving directions to a construction worker, two out of three people also failed to notice when he was replaced by another worker during a staged interruption (FIGURE 3.7). Out of sight, out of mind.

FIGURE 3.7

FIGURE 3.7Change blindness While a man (in red) provides directions to a construction worker, two experimenters rudely pass between them carrying a door. During this interruption, the original worker switches places with another person wearing different-

With this forewarning, are you still vulnerable to change blindness? To find out, watch the 3-minute Video: Visual Attention, and prepare to be stunned.

With this forewarning, are you still vulnerable to change blindness? To find out, watch the 3-minute Video: Visual Attention, and prepare to be stunned.

A Swedish research team discovered that people’s blindness extends to their own choices. Petter Johansson and his colleagues (2005, 2014) showed 120 volunteers two female faces and asked which face was more attractive. After putting both photos face down, they handed viewers the one chosen and invited them to explain why they preferred it. But on 3 of 15 occasions, the researchers used sleight-

FIGURE 3.8

FIGURE 3.8Choice blindness Pranksters Petter Johansson, Lars Hall, and others (2005) invited people to choose preferred faces. On occasion, they asked people to explain their preference for the unchosen photo. Most—

99

Change deafness can also occur. In one experiment, 40 percent of people focused on repeating a list of words that someone spoke failed to notice a change in the person speaking (Vitevitch, 2003). In two follow-

The dual-

FIGURE 3.9

FIGURE 3.9The popout phenomenon

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Explain three attentional principles that magicians may use to fool us.

Our selective attention allows us to focus on only a limited portion of our surroundings. Inattentional blindness explains why we don’t perceive some things when we are distracted by others. And change blindness happens when we fail to notice a relatively unimportant change in our environment. All these principles help magicians fool us, as they direct our attention elsewhere to perform their tricks.

REVIEW: Brain States and Consciousness

|

REVIEW | Brain States and Consciousness |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-

3-

Since 1960, under the influence of cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive neuroscience, our awareness of ourselves and our environment—our consciousness—has reclaimed its place as an important area of research. After initially claiming consciousness as its area of study in the nineteenth century, psychologists had abandoned it in the first half of the twentieth century, turning instead to the study of observable behavior because they believed consciousness was too difficult to study scientifically.

3-

Scientists studying the brain mechanisms underlying consciousness and cognition have discovered that the mind processes information on two separate tracks, one operating at an explicit, conscious level (conscious sequential processing) and the other at an implicit, unconscious level (unconscious parallel processing). This dual processing affects our perception, memory, attitudes, and other cognitions.

3-

We selectively attend to, and process, a very limited portion of incoming information, blocking out much and often shifting the spotlight of our attention from one thing to another. Parallel processing takes care of the routine business, while sequential processing is best for solving new problems that require our attention. Focused intently on one task, we often display inattentional blindness to other events and change blindness to changes around us.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

consciousness cognitive neuroscience dual processing blindsight parallel processing selective attention inattentional blindness change blindness | the processing of many aspects of a problem simultaneously; the brain’s natural mode of information processing for many functions. failing to notice changes in the environment. a condition in which a person can respond to a visual stimulus without consciously experiencing it. our awareness of ourselves and our environment. failing to see visible objects when our attention is directed elsewhere. the principle that information is often simultaneously processed on separate conscious and unconscious tracks. the interdisciplinary study of the brain activity linked with cognition (including perception, thinking, memory, and language). the focusing of conscious awareness on a particular stimulus. |

Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.

100