10.1 What Is Intelligence?

intelligence the mental potential to learn from experience, solve problems, and use knowledge to adapt to new situations.

10-

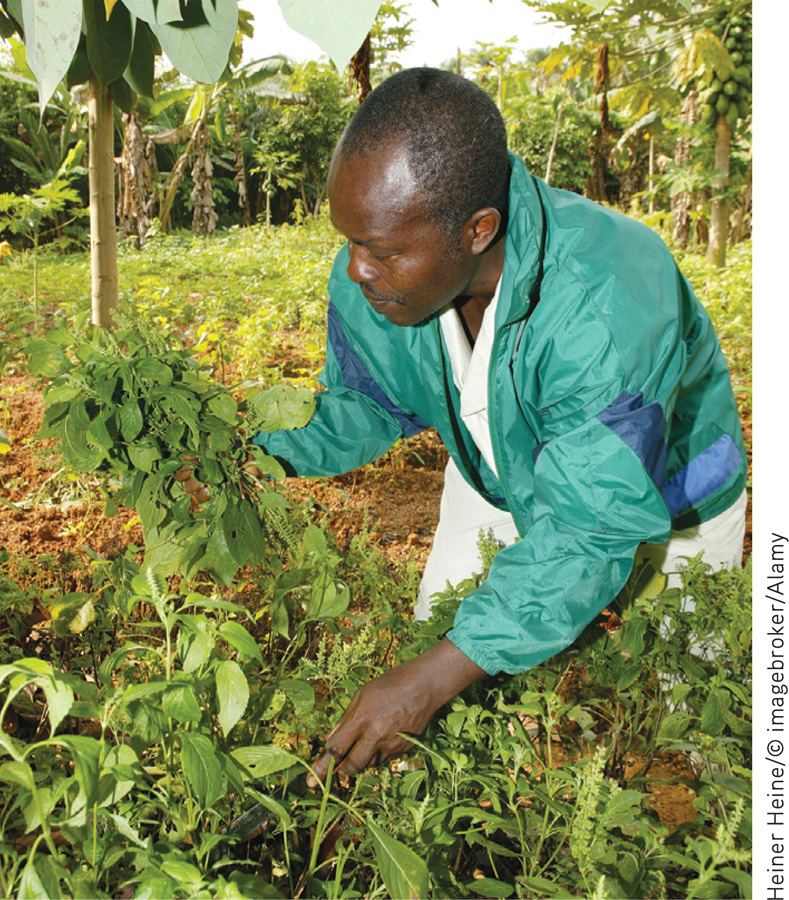

In many studies, intelligence has been defined as whatever intelligence tests measure, which has tended to be school smarts. But intelligence is not a quality like height or weight, which has the same meaning to everyone worldwide. People assign the term intelligence to the qualities that enable success in their own time and culture (Sternberg & Kaufman, 1998). In Cameroon’s equatorial forest, intelligence may be understanding the medicinal qualities of local plants. In a North American high school, it may be mastering difficult concepts in tough courses. In both places, intelligence is the mental potential to learn from experience, solve problems, and use knowledge to adapt to new situations.

You probably know some people with talents in science, others who excel in the humanities, and still others gifted in athletics, art, music, or dance. You may also know a talented artist who is stumped by the simplest math problem, or a brilliant math student who struggles when discussing literature. Are all these people intelligent? Could you rate their intelligence on a single scale? Or would you need several different scales?

Spearman’s General Intelligence Factor and Thurstone’s Response

general intelligence (g) a general intelligence factor that, according to Spearman and others, underlies specific mental abilities and is therefore measured by every task on an intelligence test.

“g is one of the most reliable and valid measures in the behavioral domain … and it predicts important social outcomes such as educational and occupational levels far better than any other trait.”

Behavior geneticist Robert Plomin (1999)

Charles Spearman (1863–

This idea of a general mental capacity expressed by a single intelligence score was controversial in Spearman’s day, and so it remains. One of Spearman’s early opponents was L. L. Thurstone (1887–

We might, then, liken mental abilities to physical abilities: The ability to run fast is distinct from the eye-

Satoshi Kanazawa (2004, 2010) argues that general intelligence evolved as a form of intelligence that helps people solve novel (unfamiliar) problems—

Question

dkC2ABG1bxNi32tRdmDfipzI90cRP0WjrEN9B1H4fAyZAccumHvo7VqWwblaFF5/eWG8zEoFvGQnbl2lJUAX7m138pvLfgGosn2gxMV25nfGKv4iRRv/MK4K2azXfCtfQt3IWPpluNnTNF/EE0J7Qu9zbcygR9/GAPgrNoOeG1VXXVFj6OliJDuyJ5mBvidxwSlyoiNdEVK0DrpLVl2V07Ta2KFt+4VjyBAVPrD+TWPJ8HT4EnjJae+5aY6USrc4vijFTvFcO+tcqNJolOPN/QmlBSV1ALRKNBoC1nriTzA=387

Theories of Multiple Intelligences

10-

Other psychologists, particularly since the mid-

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences

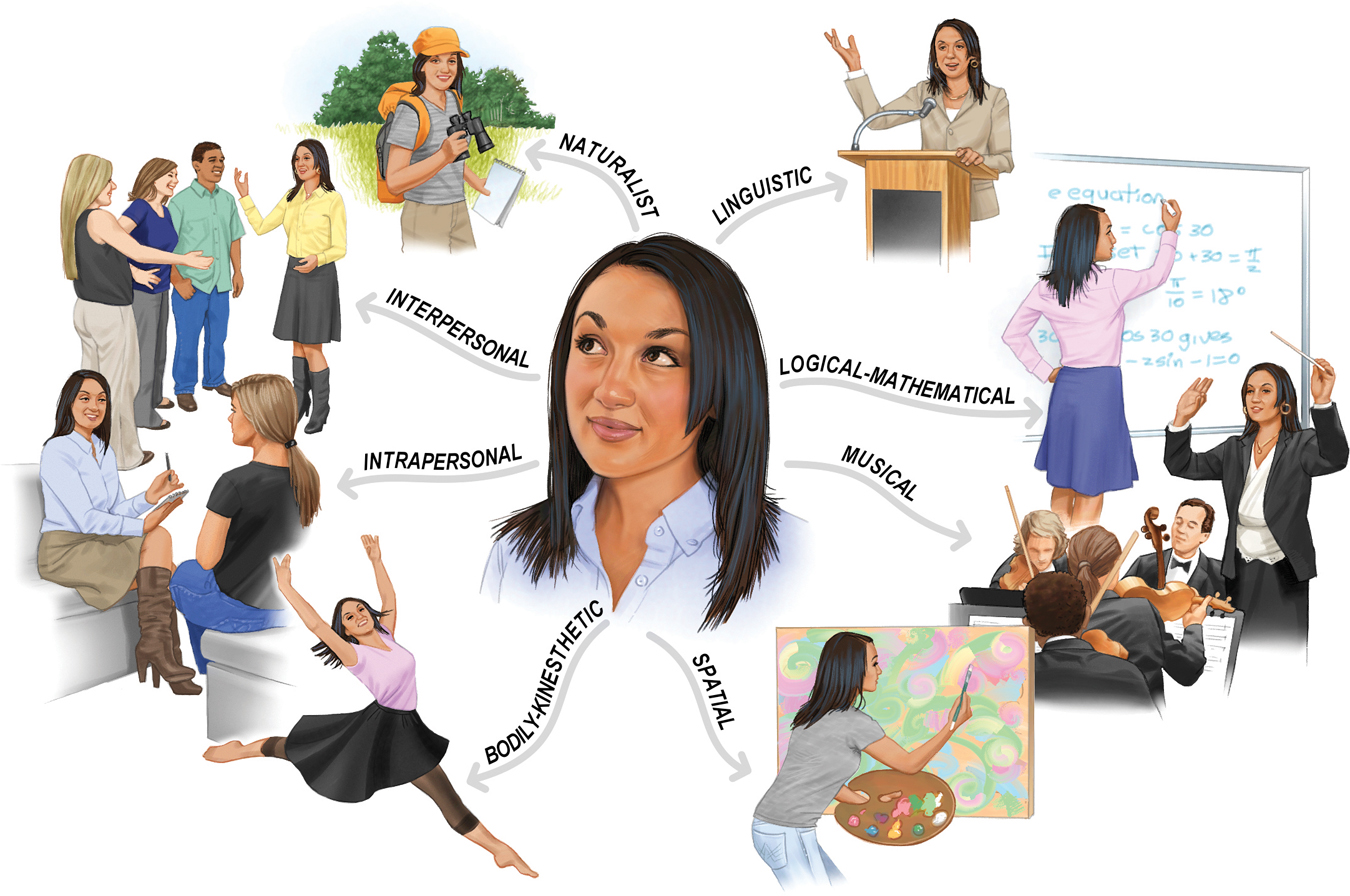

Howard Gardner has identified eight relatively independent intelligences, including the verbal and mathematical aptitudes assessed by standard tests (FIGURE 10.1). Thus, the computer programmer, the poet, the street-

Figure 10.1

Figure 10.1Gardner’s eight intelligences Gardner has also proposed a ninth possible intelligence—

savant syndrome a condition in which a person otherwise limited in mental ability has an exceptional specific skill, such as in computation or drawing.

Gardner (1983, 2006; 2011; Davis et al., 2011) views these intelligence domains as multiple abilities that come in different packages. Brain damage, for example, may destroy one ability but leave others intact. And consider people with savant syndrome. Despite their island of brilliance, these people often score low on intelligence tests and may have limited or no language ability (Treffert & Wallace, 2002). Some can compute complicated calculations quickly and accurately, or identify the day of the week corresponding to any given historical date, or render incredible works of art or musical performance (Miller, 1999).

388

About 4 in 5 people with savant syndrome are males, and many also have autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a developmental disorder. The late memory whiz Kim Peek (who did not have ASD) inspired the movie Rain Man. In 8 to 10 seconds, he could read and remember a page. During his lifetime, he memorized 9000 books, including Shakespeare’s works and the Bible. He could provide GPS-

Sternberg’s Three Intelligences

“You have to be careful, if you’re good at something, to make sure you don’t think you’re good at other things that you aren’t necessarily so good at…. Because I’ve been very successful at [software development] people come in and expect that I have wisdom about topics that I don’t.”

Philanthropist Bill Gates (1998)

Robert Sternberg (1985, 2011) agrees with Gardner that there is more to success than traditional intelligence and that we have multiple intelligences. But his triarchic theory proposes three, not eight or nine, intelligences:

- Analytical (academic problem-

solving) intelligence is assessed by intelligence tests, which present well-defined problems having a single right answer. Such tests predict school grades reasonably well and vocational success more modestly. - Creative intelligence is demonstrated in innovative smarts: the ability to generate novel ideas.

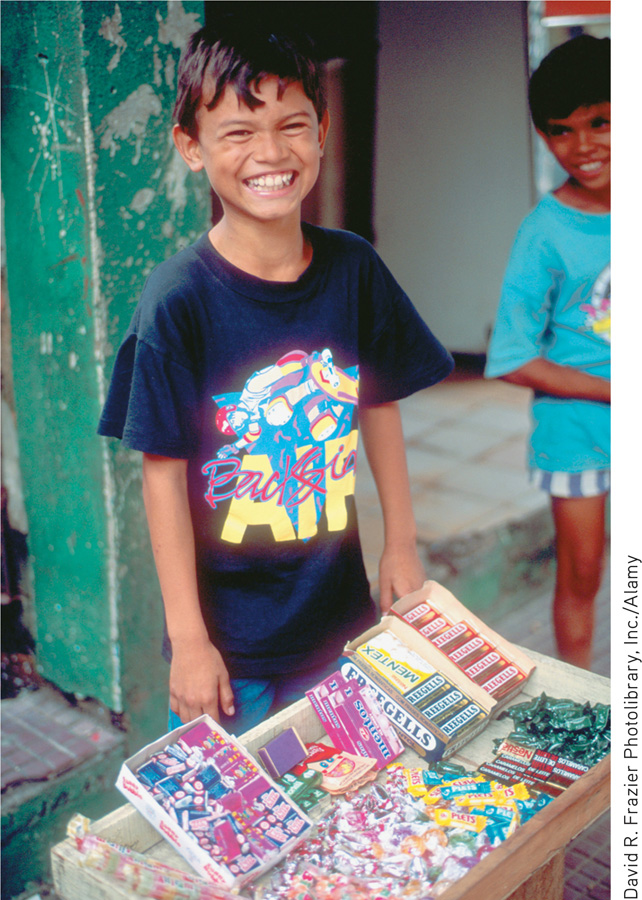

- Practical intelligence is required for everyday tasks that are not well-

defined, and that may have many possible solutions. Managerial success, for example, depends less on academic problem- solving skills than on a shrewd ability to manage oneself, one’s tasks, and other people. Sternberg and Richard Wagner (1993, 1995; Wagner, 2011) offer a test of practical managerial intelligence that measures skill at writing effective memos, motivating people, delegating tasks and responsibilities, reading people, and promoting one’s own career. Business executives who score relatively high on this test tend to earn high salaries and receive high performance ratings.

389

With support from the U.S. College Board (which administers the widely used SAT Reasoning Test to U.S. college and university applicants), Sternberg (2006, 2007, 2010) and a team of collaborators have developed new measures of creativity (such as thinking up a caption for an untitled cartoon) and practical thinking (such as figuring out how to move a large bed up a winding staircase). These more comprehensive assessments improve prediction of American students’ first-

Gardner and Sternberg differ on specific points, but they agree on two important points: Multiple abilities can contribute to life success, and differing varieties of giftedness add spice to life and challenges for education. Under their influence, many teachers have been trained to appreciate such variety and to apply multiple intelligence theories in their classrooms.

Criticisms of Multiple Intelligence Theories

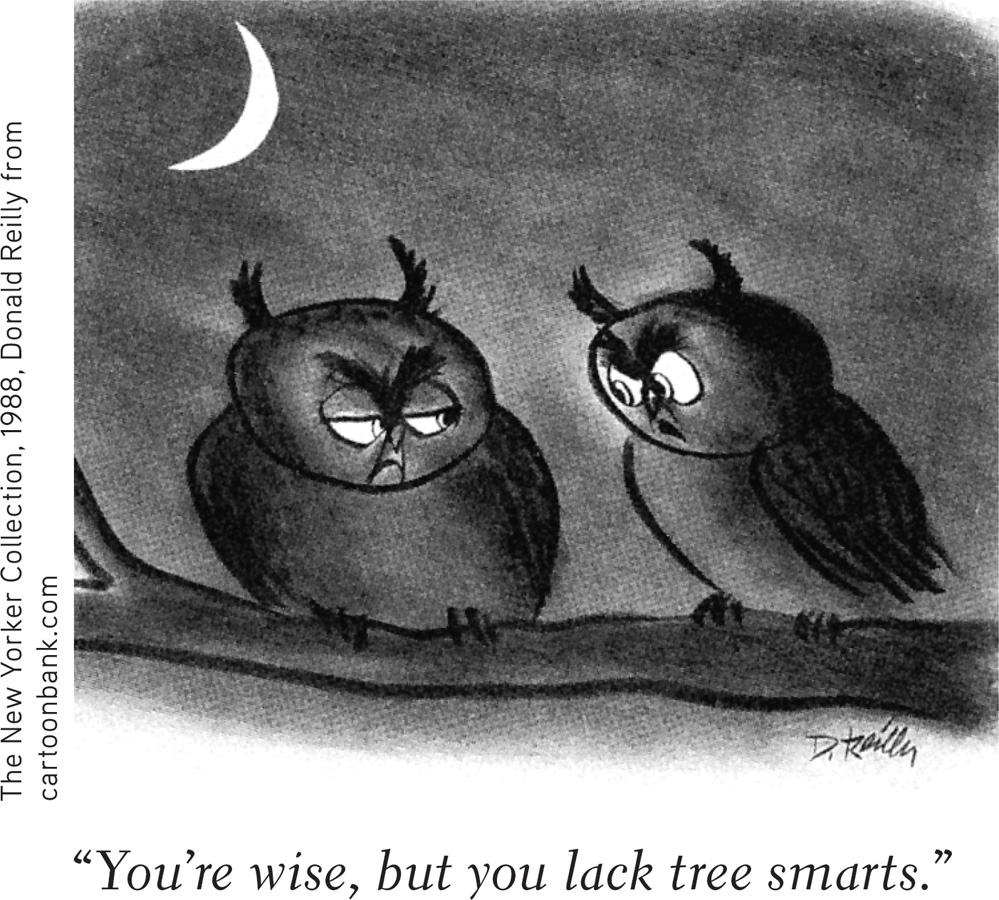

Wouldn’t it be nice if the world were so just that a weakness in one area would be compensated by genius in another? Alas, say critics, the world is not just (Ferguson, 2009; Scarr, 1989). Research using factor analysis confirms that there is a general intelligence factor (Johnson et al., 2008): g matters. It predicts performance on various complex tasks and in various jobs (Gottfredson, 2002a,b, 2003a,b; see also FIGURE 10.2). Much as jumping ability is not a predictor of jumping performance when the bar is set a foot off the ground—

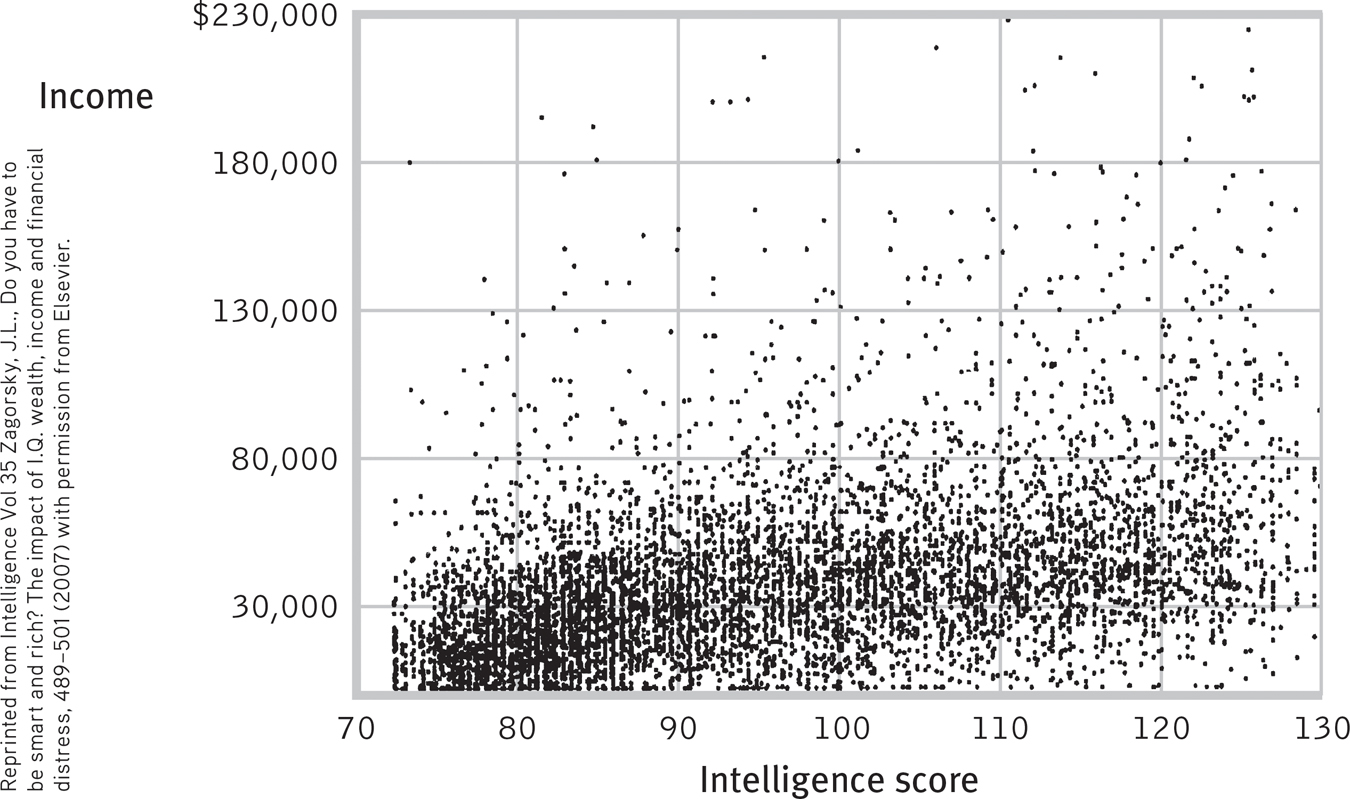

Figure 10.2

Figure 10.2Smart and rich? Jay Zagorsky (2007) tracked 7403 participants in the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth across 25 years. As shown in this scatterplot, their intelligence scores correlated +.30, a moderate positive correlation, with their later income. Each dot indicates a given youth’s intelligence score and later adult income.

390

For more on how self-

Even so, “success” is not a one-

Question

5RY53ZLsyuIlNGxdgRmcL6T845LBjqL8ZAiUAH64f8DLmdfPpJrxxHyDu/i4Elee89EM9F5oAa2az0SMguyB0um2CXi+yoSzTyyacxmrgOnmpzldYlkKeVjjUt29k4Ucb+p3ntnHkTYaS7VAfA2uh1BV63RfzYzKI+/lQJpOF9sqeh1UQQrUEdhNfnti+LeXns42Hrb6HEpFhzGU2fhYgQBLQcc5Jo5EQN2GCiJTBse0QlY2S4QDClSkwegTh8IN1RRzj2hKcQ78CPmqRETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How does the existence of savant syndrome support Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences?

People with savant syndrome have limited mental ability overall but possess one or more exceptional skills, which, according to Howard Gardner, suggests that our abilities come in separate packages rather than being fully expressed by one general intelligence that encompasses all of our talents.

Emotional Intelligence

10-

Is being in tune with yourself and others also a sign of intelligence, distinct from academic intelligence? Some researchers say Yes. They define social intelligence as the know-

One line of research has explored a specific aspect of social intelligence called emotional intelligence, consisting of four abilities (Mayer et al., 2002, 2011, 2012):

- Perceiving emotions (recognizing them in faces, music, and stories)

- Understanding emotions (predicting them and how they may change and blend)

- Managing emotions (knowing how to express them in varied situations)

- Using emotions to enable adaptive or creative thinking

emotional intelligence the ability to perceive, understand, manage, and use emotions.

391

Emotionally intelligent people are both socially aware and self-

The procrastinator’s motto: “Hard works pays off later; laziness pays off now.”

These emotional intelligence high scorers also perform modestly better on the job (O’Boyle et al., 2011). On and off the job, they can delay gratification in pursuit of long-

Some scholars, however, are concerned that emotional intelligence stretches the intelligence concept too far (Visser et al., 2006). Howard Gardner (1999) includes interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligences as two of his eight forms of multiple intelligences. But let us also, he acknowledges, respect emotional sensitivity, creativity, and motivation as important but different. Stretch intelligence to include everything we prize and the word will lose its meaning.

***

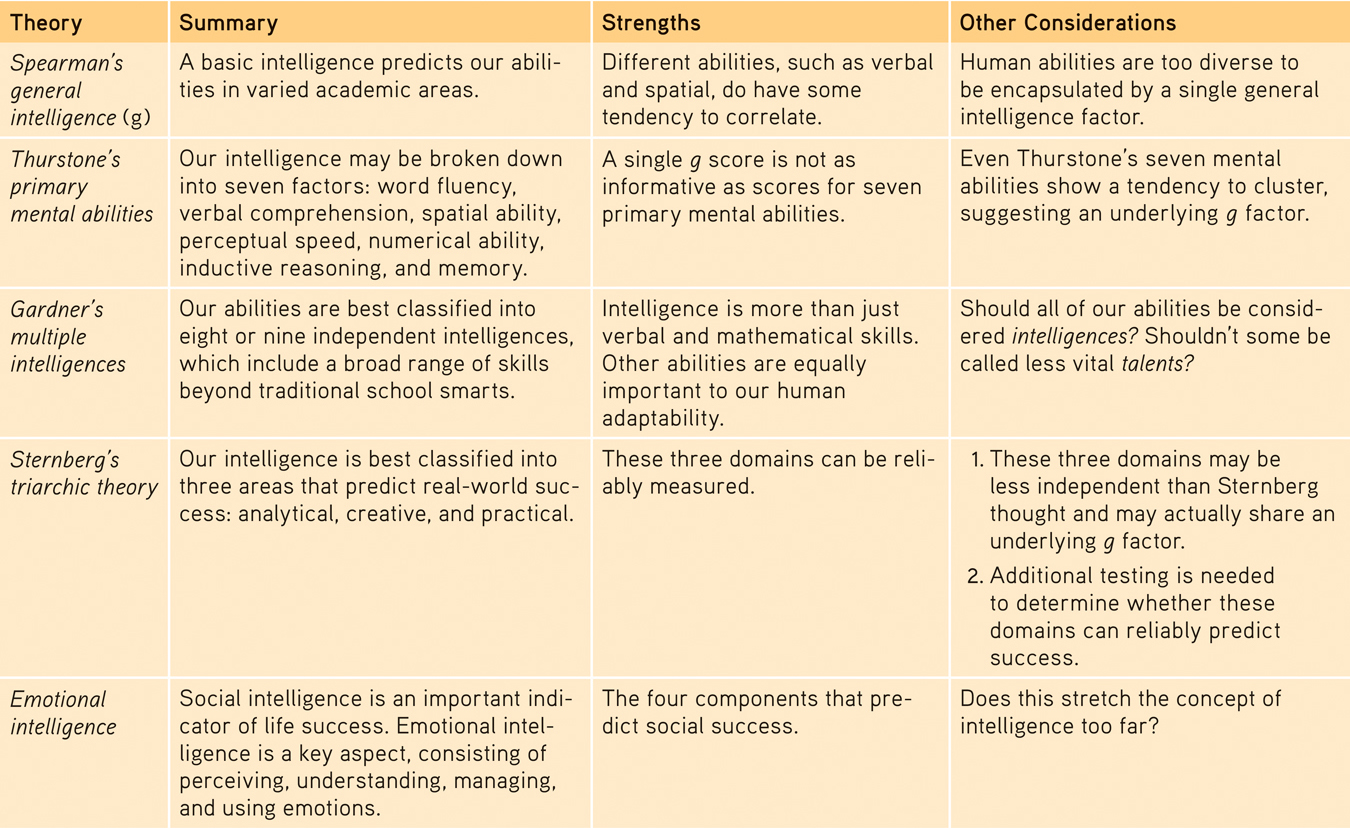

For a summary of these theories of intelligence, see TABLE 10.1.

TABLE 10.1

TABLE 10.1Comparing Theories of Intelligence

392