11.2 Hunger

A vivid demonstration of the supremacy of physiological needs came when Ancel Keys and his research team (1950) studied semistarvation among wartime conscientious objectors. After three months of normal eating, they cut in half the food intake of 36 men selected from 200 volunteers. The semistarved men became listless and apathetic as their bodies conserved energy. Eventually, their body weights stabilized at about 25 percent below their starting weights.

“Nobody wants to kiss when they are hungry.”

Journalist Dorothy Dix (1861-

More dramatic were the psychological effects. Consistent with Maslow’s idea of a needs hierarchy, the men became food obsessed. They talked food. They daydreamed food. They collected recipes, read cookbooks, and feasted their eyes on delectable forbidden foods. Preoccupied with their unfulfilled basic need, they lost interest in sex and social activities. As one participant reported, “If we see a show, the most interesting part of it is contained in scenes where people are eating. I couldn’t laugh at the funniest picture in the world, and love scenes are completely dull.”

“Nature often equips life’s essentials—

Frans de Waal, “Morals Without God?,” 2010

The semistarved men’s preoccupations illustrate how powerful motives can hijack our consciousness. When you are hungry, thirsty, fatigued, or sexually aroused, little else may seem to matter. When you’re not, food, water, sleep, or sex just don’t seem like such big things in your life, now or ever.

425

“The full person does not understand the needs of the hungry.”

Irish proverb

In University of Amsterdam studies, Loran Nordgren and his colleagues (2006, 2007) found that people in a motivational “hot” state (from fatigue, hunger, or sexual arousal) easily recalled such feelings in their own past and perceived them as driving forces in others’ behavior. (You may recall from Chapter 8 a parallel effect of our current good or bad mood on our memories.) In another experiment, people were given $4 cash they could keep or draw from to bid for foods. Hungry people overbid for a snack they would eat later when sated, and sated people underbid for a snack they would eat later when hungry (Fisher & Rangel, 2014). Likewise, when sexually motivated, men more often perceive a smile as flirtation rather than simple friendliness (Howell et al., 2012). Grocery shop with an empty stomach and you are more likely to see those jelly-

The Physiology of Hunger

11-

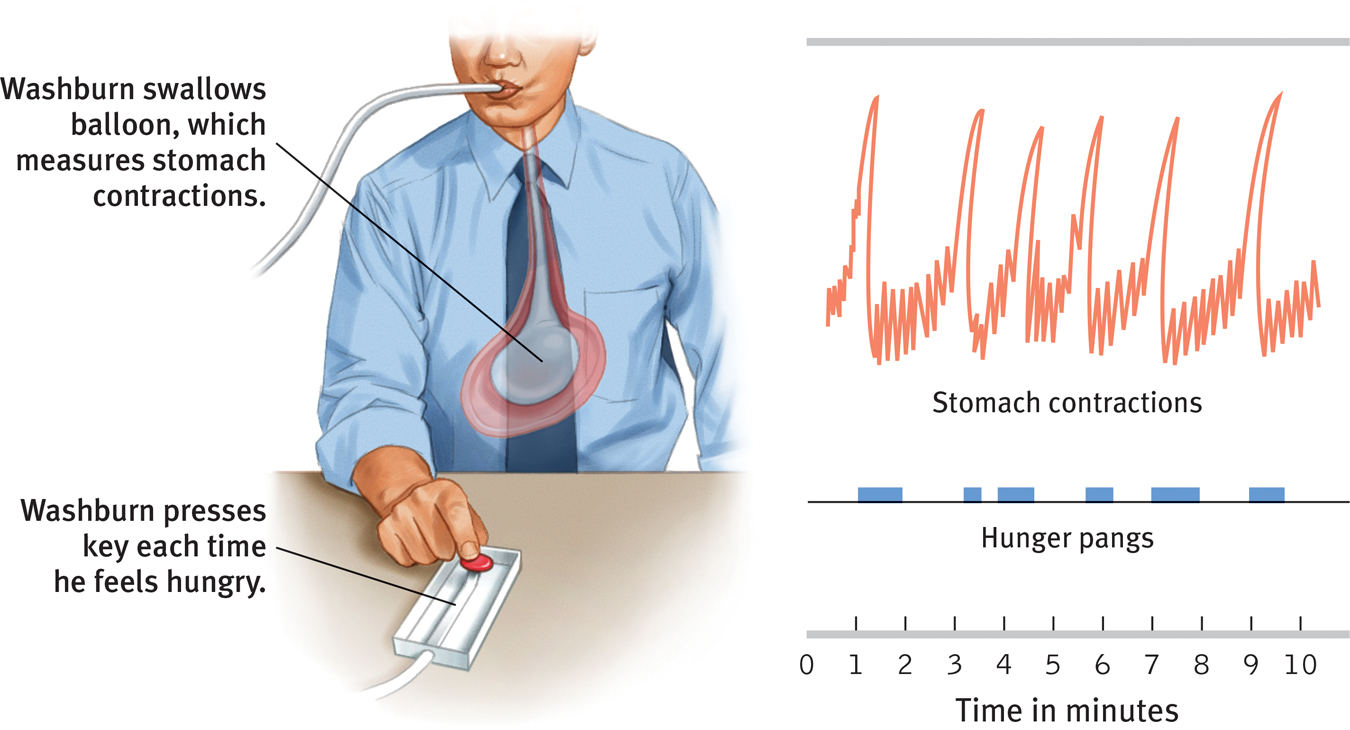

Keys’ semistarved volunteers felt their hunger because of a homeostatic system designed to maintain normal body weight and an adequate nutrient supply. But what precisely triggers hunger? Is it the pangs of an empty stomach? So it seemed to A. L. Washburn. Working with Walter Cannon (Cannon & Washburn, 1912), Washburn agreed to swallow a balloon attached to a recording device (FIGURE 11.4). When inflated to fill his stomach, the balloon transmitted his stomach contractions. Washburn supplied information about his feelings of hunger by pressing a key each time he felt a hunger pang. The discovery: Washburn was indeed having stomach contractions whenever he felt hungry.

Figure 11.4

Figure 11.4Monitoring stomach contractions Using this procedure, Washburn showed that stomach contractions (transmitted by the stomach balloon) accompany our feelings of hunger (indicated by a key press). (From Cannon, 1929.)

Can hunger exist without stomach pangs? To answer that question, researchers removed some rats’ stomachs, creating a direct path to their small intestines (Tsang, 1938). Did the rats continue to eat? Indeed they did. Some hunger similarly persists in humans whose ulcerated or cancerous stomachs have been removed.

glucose the form of sugar that circulates in the blood and provides the major source of energy for body tissues. When its level is low, we feel hunger.

If the pangs of an empty stomach are not the only source of hunger, what else matters?

Body Chemistry and the Brain

People and other animals automatically regulate their caloric intake to prevent energy deficits and maintain a stable body weight. This suggests that somehow, somewhere, the body is keeping tabs on its available resources. One such resource is the blood sugar glucose. Increases in the hormone insulin (secreted by the pancreas) diminish blood glucose, partly by converting it to stored fat. If your blood glucose level drops, you won’t consciously feel the lower blood sugar. But your brain, which is automatically monitoring your blood chemistry and your body’s internal state, will trigger hunger. Signals from your stomach, intestines, and liver (indicating whether glucose is being deposited or withdrawn) all signal your brain to motivate eating or not.

426

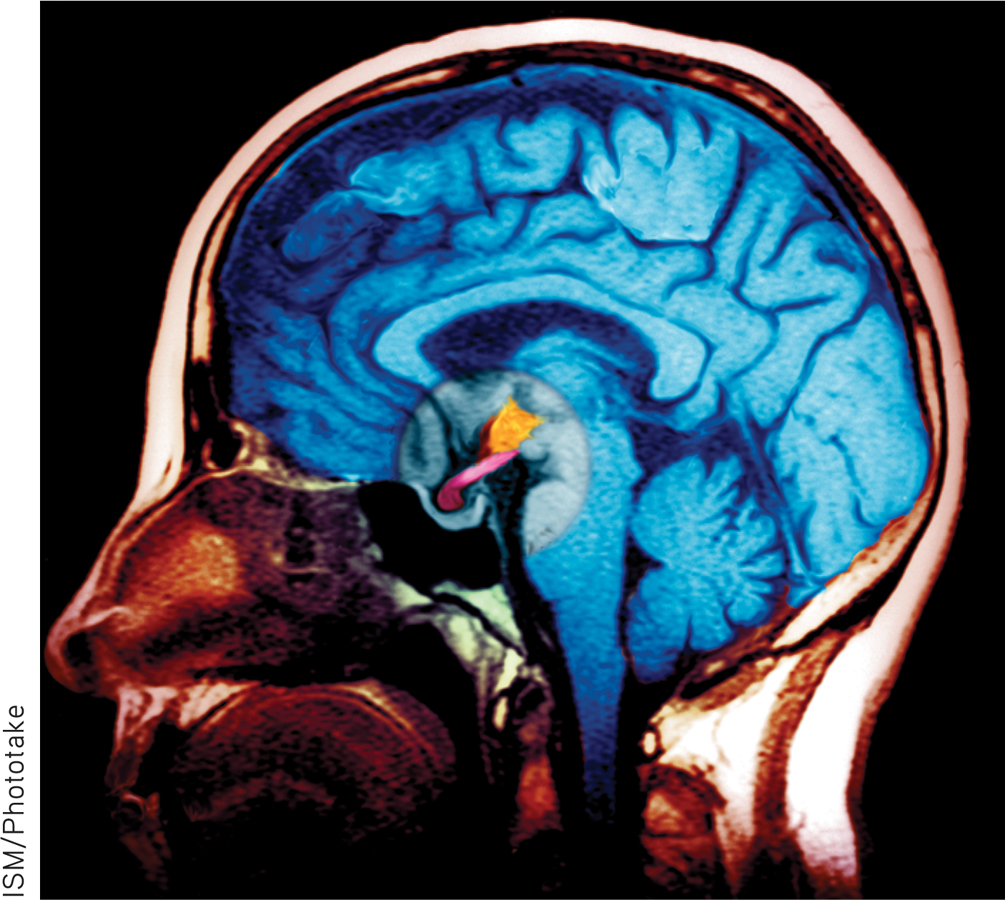

How does the brain integrate these messages and sound the alarm? The work is done by several neural areas, some housed deep in the brain within the hypothalamus, a neural traffic intersection (FIGURE 11.5). For example, one neural arc (called the arcuate nucleus) has a center that secretes appetite-

Figure 11.5

Figure 11.5The hypothalamus The hypothalamus (colored orange) performs various body maintenance functions, including control of hunger. Blood vessels supply the hypothalamus, enabling it to respond to our current blood chemistry as well as to incoming neural information about the body’s state.

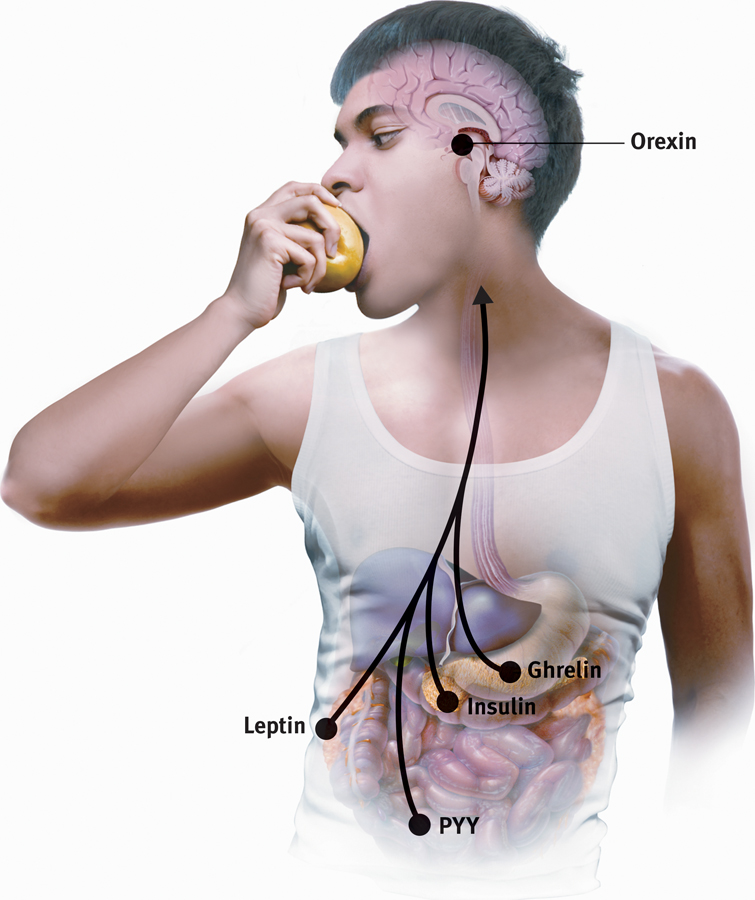

Blood vessels connect the hypothalamus to the rest of the body, so it can respond to our current blood chemistry and other incoming information. One of its tasks is monitoring levels of appetite hormones, such as ghrelin, a hunger-

Figure 11.6

Figure 11.6The appetite hormones

- Ghrelin: Hormone secreted by empty stomach; sends “I’m hungry” signals to the brain.

- Insulin: Hormone secreted by pancreas; controls blood glucose.

- Leptin: Protein hormone secreted by fat cells; when abundant, causes brain to increase metabolism and decrease hunger.

- Orexin: Hunger-

triggering hormone secreted by hypothalamus. - PYY: Digestive tract hormone; sends “I’m not hungry” signals to the brain.

set point the point at which your “weight thermostat” is supposedly set. When your body falls below this weight, increased hunger and a lowered metabolic rate may combine to restore the lost weight.

Experimental manipulation of appetite hormones has raised hopes for an appetite-

427

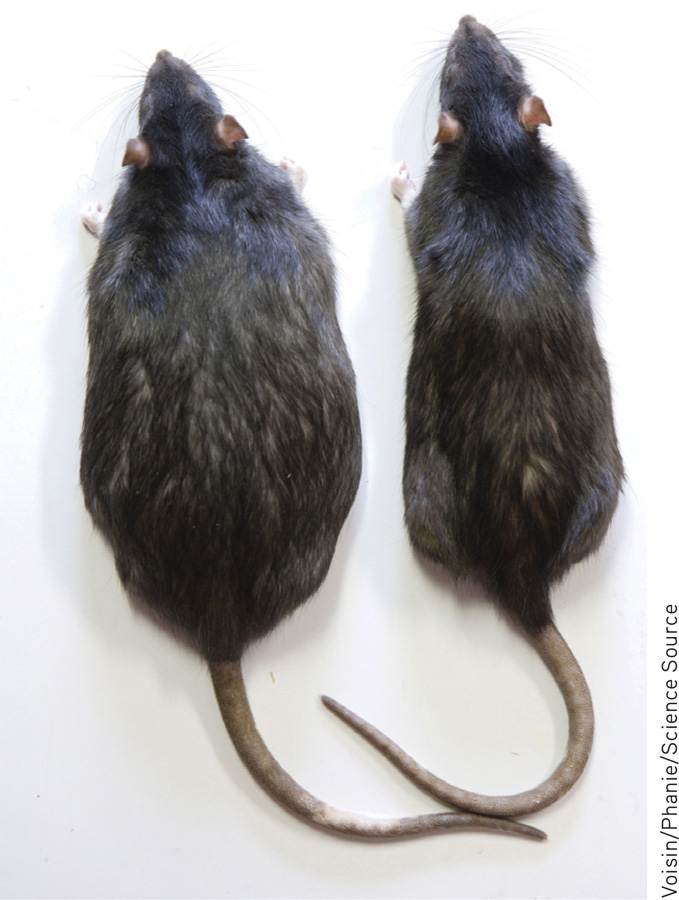

For an interactive and visual tutorial on the brain and eating, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Hunger and the Fat Rat.

For an interactive and visual tutorial on the brain and eating, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Hunger and the Fat Rat.

basal metabolic rate the body’s resting rate of energy expenditure.

The complex interaction of appetite hormones and brain activity may help explain the body’s apparent predisposition to maintain itself at a particular weight. When semistarved rats fall below their normal weight, their “weight thermostat” signals the body to restore the lost weight. Fat cells cry out (so to speak) “Feed me!” and grab glucose from the bloodstream (Ludwig & Friedman, 2014). Thus, hunger increases and energy expenditure decreases. This stable weight toward which semistarved rats return is their set point (Keesey & Corbett, 1983). In rats and humans, heredity influences body type and approximate set point.

Our bodies regulate weight through the control of food intake, energy output, and basal metabolic rate—the rate of energy expenditure for maintaining basic body functions when at rest. By the end of their 6 months of semistarvation, the men who participated in Keys’ experiment had stabilized at three-

Over the next 40 years you will eat about 20 tons of food. If, during those years, you increase your daily intake by just .01 ounce more than required for your energy needs, you will gain an estimated 24 pounds (Martin et al., 1991).

Some researchers, however, doubt that our bodies have a preset tendency to maintain optimum weight (Assanand et al., 1998). They point out that slow, sustained changes in body weight can alter one’s set point, and that psychological factors also sometimes drive our feelings of hunger. Given unlimited access to a wide variety of tasty foods, people and other animals tend to overeat and gain weight (Raynor & Epstein, 2001). For these reasons, some researchers have abandoned the idea of a biologically fixed set point. They prefer the term settling point to indicate the level at which a person’s weight settles in response to caloric intake and expenditure (which are influenced by environment as well as biology).

Question

Ph+iW/HzROTjKh/ZXLcFUK8vvT3GzcLyT5LPYn3MsXVHy0U2kqFo/VaTTqSyzvGAq5/wwkIvzs+4LwLpcANqkILoeP2uQWobtN9t1cO7ejRbxxigk2jw+pbUWhJFJtIugwKarOK9YYhCXXoViqdEq84s2tSo+K0Q6efDrpoHHQiV0itxOVKbafsgPBCoSOPgtsCPhBRnZKjagyJr9FzAk6XWzFnKfayohHgraOr94p+rwLta3Z/5Kw==RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Hunger occurs in response to ______________ (low/high) blood glucose and ______________ (low/high) levels of ghrelin.

low; high

The Psychology of Hunger

11-

Our internal hunger games are indeed pushed by our physiological state—

428

Taste Preferences: Biology and Culture

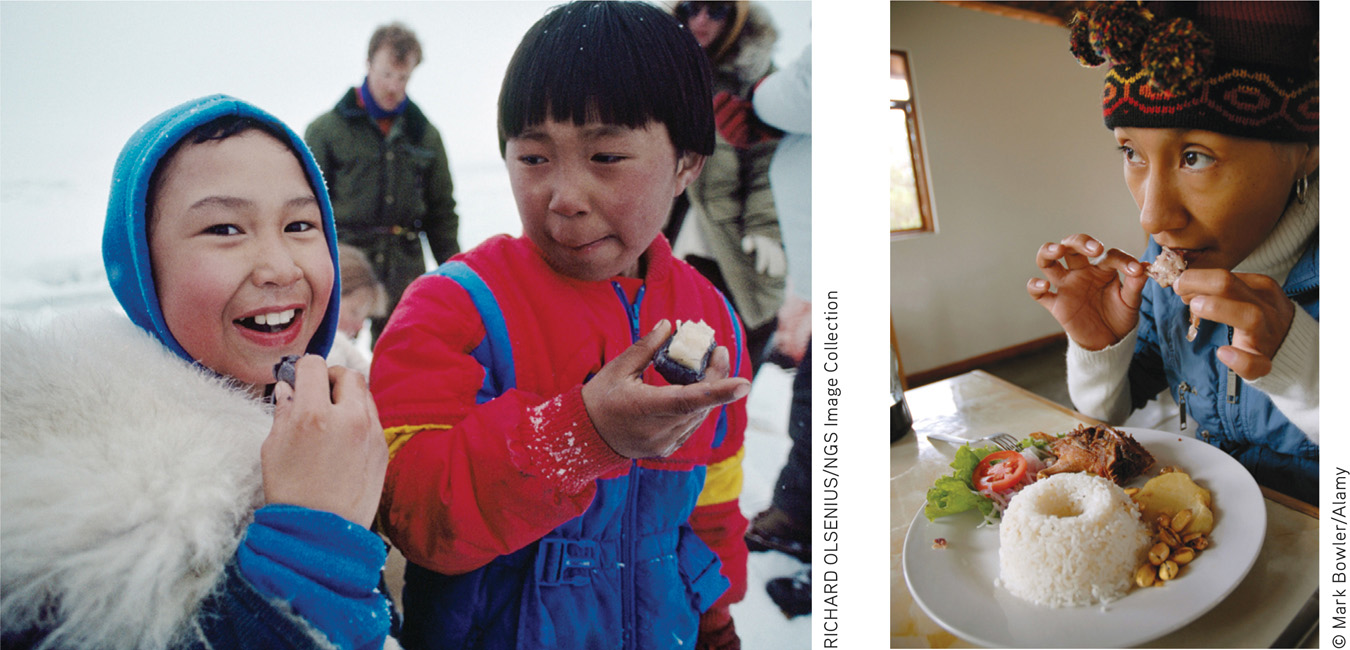

Body chemistry and environmental factors together influence not only the when of hunger, but also the what—

Our preferences for sweet and salty tastes are genetic and universal. Other taste preferences are conditioned, as when people given highly salted foods develop a liking for excess salt (Beauchamp, 1987), or when people who have been sickened by a food develop an aversion to it. (The frequency of children’s illnesses provides many chances for them to learn food aversions.)

Culture affects taste, too. Bedouins enjoy eating the eye of a camel, which most North Americans would find repulsive. Many Japanese people enjoy nattó, a fermented soybean dish that “smells like the marriage of ammonia and a tire fire,” reports smell expert Rachel Herz (2012). Although many Westerners find this disgusting, Asians, she adds, are often repulsed by what Westerners love—

Rats tend to avoid unfamiliar foods (Sclafani, 1995). So do we, especially animal-

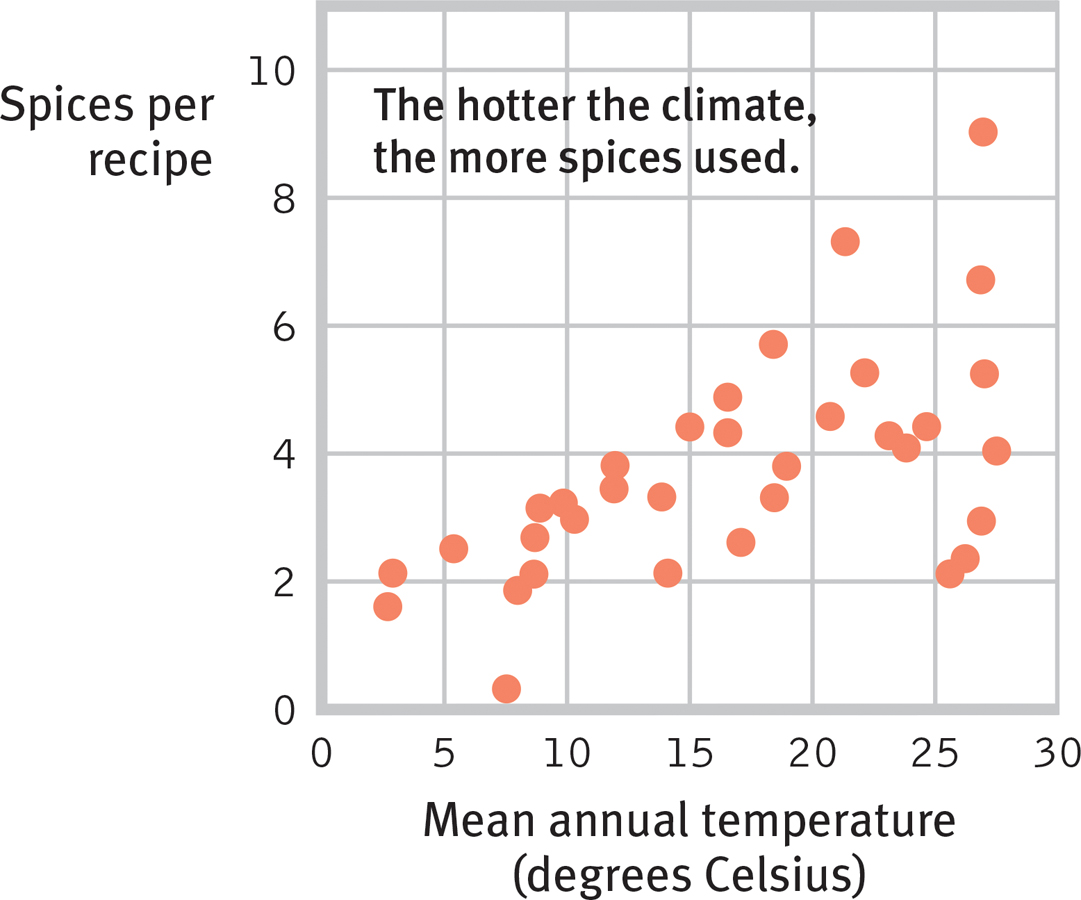

Other taste preferences also are adaptive. For example, the spices most commonly used in hot-

Figure 11.7

Figure 11.7Hot cultures like hot spices Countries with hot climates, in which food historically spoiled more quickly, feature recipes with more bacteria-

429

Situational Influences on Eating

To a surprising extent, situations also control our eating—

- Do you eat more when eating with others? Most of us do (Herman et al., 2003; Hetherington et al., 2006). After a party, you may realize you’ve overeaten. This happens because the presence of others tends to amplify our natural behavior tendencies. (You’ll hear more about social facilitation in Chapter 13.)

Consider how researchers test some of these ideas with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If Larger Dinner Plates Make People Fat? - Unit bias occurs with similar mindlessness. At France’s National Center for Scientific Research, Andrew Geier and his colleagues (2006) wondered why French waistlines are smaller than American waistlines. From soda drinks to yogurt sizes, the French offer foods in smaller portion sizes. Does it matter? (One could as well order two small sandwiches as one large one.) To find out, the investigators offered people varieties of free snacks. For example, in the lobby of an apartment house, they laid out either full or half pretzels, big or little Tootsie Rolls, or a big bowl of M&M’s with either a small or large serving scoop. Their consistent result: Offered a supersized standard portion, people put away more calories. In another study, people offered pasta ate more when given a big plate (Van Ittersum & Wansink, 2012). Children also eat more when using adult-

sized (rather than child- sized) dishware (DiSantis et al., 2013). Even nutrition experts helped themselves to 31 percent more ice cream when given a big bowl rather than a small one, and 15 percent more when scooping with a big rather than a small scoop (Wansink, 2006, 2007). People pour more into and drink more from short, wide than tall, narrow glasses. And they take more of easier- to- reach food on buffet lines (Marteau et al., 2012). Portion size matters.

- Food variety also stimulates eating. Offered a dessert buffet, we eat more than we do when choosing a portion from one favorite dessert. For our early ancestors, variety was healthy. When foods were abundant and varied, eating more provided a wide range of vitamins and minerals and produced fat that protected them during winter cold or famine. When a bounty of varied foods was unavailable, eating less extended the food supply until winter or famine ended (Polivy et al., 2008; Remick et al., 2009).

Question

vC+fVe6J/5j7hyU4F7oQeLaLI+bf2NNso9Fj6WI3Rc/u8g17epCqSfXq2lkztB+VK1vxU80RWsLXnizdXAL3h1ky7lGSUB6FKBMdcIrI8uCPe0DVsZU+ask+3yw6CSWtqBFEs2/qggNsLSczF8DMFYR98ivv1aTK1ZFqtzurD/eU0YeUJKVa3HM+pAHIIZGXrdk5r6okPvTLrnsbt0JLnWpz04beMNkc3QAm/TrJq3C0s0NRgN/PMw== For a 7-

For a 7-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- After an eight-

hour hike without food, your long- awaited favorite dish is placed in front of you, and your mouth waters in anticipation. Why?

You have learned to respond to the sight and aroma that signal the food about to enter your mouth. Both psychological cues (low blood sugar) and physiological cues (anticipation of the tasty meal) heighten your experienced hunger.

Obesity and Weight Control

11-

Obesity can be socially toxic, by affecting both how you are treated and how you feel about yourself. Obesity has been associated with lower psychological well-

430

The Physiology of Obesity

Our bodies store fat for good reason. Fat is an ideal form of stored energy—

In parts of the world where food and sweets are now abundantly available, the rule that once served our hungry distant ancestors—

- between 1980 and 2013 the proportion of overweight adults increased from 29 to 37 percent among the world’s men, and from 30 to 38 percent among women.

- over the last 33 years, no country has reduced its obesity rate. Not one.

- national variations are huge, with the percentage overweight ranging from 85 percent in Tonga to 3 percent in Timor-

Leste.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an overweight person has a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or more; someone obese has a BMI of 30 or more. (See www.tinyurl.com/

“American men, on average, say they weigh 196 pounds and women say they weigh 160 pounds. Both figures are nearly 20 pounds heavier than in 1990.”

Elizabeth Mendes, www.gallup.com, 2011

In one digest of 97 studies of 2.9 million people, being simply overweight was not a health risk, while being obese was (Flegal et al., 2013). Fitness matters more than being a little overweight. But significant obesity increases the risk of diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, gallstones, arthritis, and certain types of cancer, thus increasing health care costs and shortening life expectancy (de Gonzales et al., 2010; Jarrett et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2009). Extreme obesity increases risk of suicidal behaviors (Wagner et al., 2013). Research also has linked women’s obesity to their risk of late-

Set Point and Metabolism Research on the physiology of obesity challenges the stereotype of severely overweight people being weak-

Lean people also seem naturally disposed to move about. They burn more calories than do energy-

The Genetic Factor Do our genes predispose us to eat more or less? To burn more calories by fidgeting or fewer by sitting still? Studies confirm a genetic influence on body weight. Consider two examples:

431

- Despite shared family meals, adoptive siblings’ body weights are uncorrelated with one another or with those of their adoptive parents. Rather, people’s weights resemble those of their biological parents (Grilo & Pogue-

Geile, 1991). - Identical twins have closely similar weights, even when raised apart (Hjelmborg et al., 2008; Plomin et al., 1997). Across studies, their weight correlates +.74. The much lower +.32 correlation among fraternal twins suggests that genes explain two-

thirds of our varying body mass (Maes et al., 1997).

The Food and Activity Factors Genes tell an important part of the obesity story. But environmental factors are mighty important, too.

Studies in Europe, Japan, and the United States show that children and adults who suffer from sleep loss are more vulnerable to obesity (Keith et al., 2006; Nedeltcheva et al., 2010; Taheri, 2004a,b). With sleep deprivation, the levels of leptin (which reports body fat to the brain) fall, and ghrelin (the appetite-

Social influence is another factor. One 32-

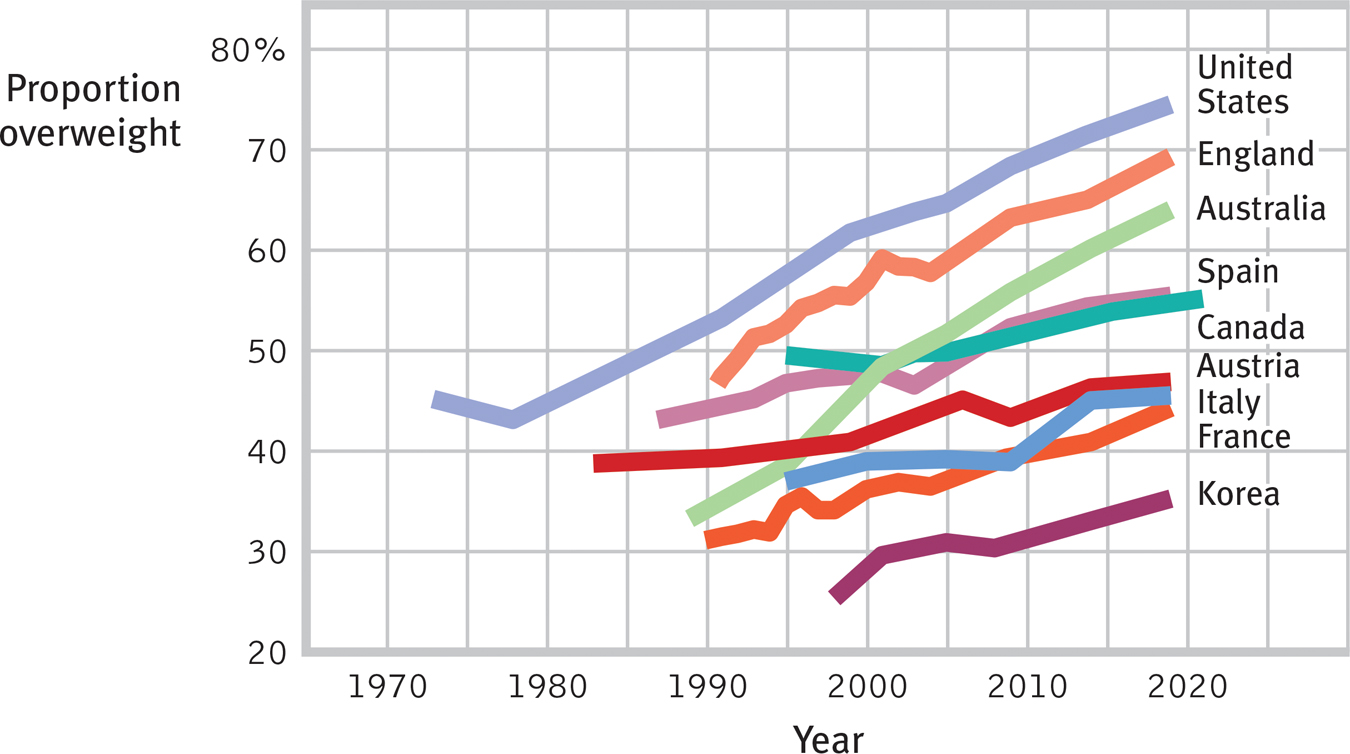

The strongest evidence that environment influences weight comes from our fattening world (FIGURE 11.8). What explains this growing problem? Changing food consumption and activity levels are at work. We are eating more and moving less, with lifestyles sometimes approaching those of animal feedlots (where farmers fatten inactive animals). In the United States, jobs requiring moderate physical activity declined from about 50 percent in 1960 to 20 percent in 2011 (Church et al., 2011). Worldwide, 31 percent of adults (including 43 percent of Americans and 25 percent of Europeans) are now sedentary, which means they average less than 20 minutes per day of moderate activity such as walking (Hallal et al., 2012). Sedentary occupations increase the chance of being overweight, as 86 percent of U.S. truck drivers reportedly are (Jacobson et al., 2007).

Figure 11.8

Figure 11.8Past and projected overweight rates, by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

432

“We put fast food on every corner, we put junk food in our schools, we got rid of [physical education classes], we put candy and soda at the checkout stand of every retail outlet you can think of. The results are in. It worked.”

Harold Goldstein, Executive Director of the California Center for Public Health Advocacy, 2009, when imagining a vast U.S. national experiment to encourage weight gain

The “bottom” line: New stadiums, theaters, and subway cars—

Note how these findings reinforce a familiar lesson from Chapter 10’s study of intelligence: There can be high levels of heritability (genetic influence on individual differences) without heredity explaining group differences. Genes mostly determine why one person today is heavier than another. Environment mostly determines why people today are heavier than their counterparts 50 years ago. Our eating behavior also demonstrates the now-

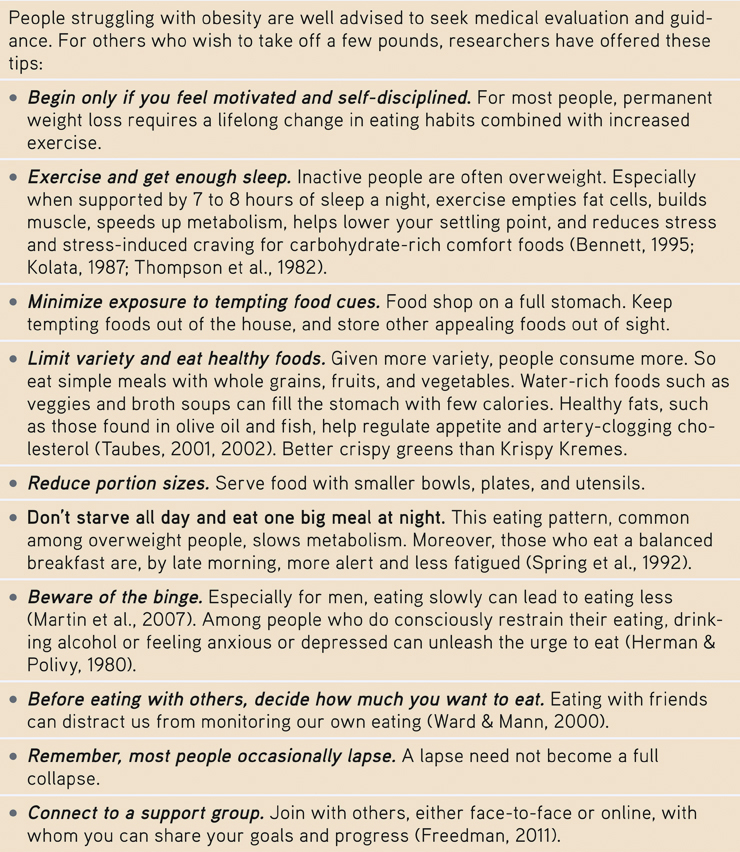

TABLE 11.1

TABLE 11.1Waist Management

Question

cm2MskVzLGN5C5UL/d0Imbe+qUgJXKF/TgX0M7gMai1DXGaLsnPXZFO+kxu+9k4YJSdq878US8hqSU4QFLZB1NG+1qO6Sfgz3i//ryW6/Ql0Z4xeVrVvAwRGNqRt2AQCHlOo7OGyZ1B1KqFNuzw0NWiYMyi8EMzPbRsZfMjZ4vidw7RZosassUfkV6erJ0BGtqglyQnIIs+BuvBKBOiWc5GVsRAHZyxK7U5kPkiNsHAXMFoHM5QZ4U7Ve69g14QUZ0zqjA==RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why can two people of the same height, age, and activity level maintain the same weight, even if one of them eats much less than the other does?

Individuals have very different set points and genetically influenced metabolism levels, causing them to burn calories differently.

433