11.3 Sexual Motivation

asexual having no sexual attraction to others.

Sex is a part of life. For all but the tiny fraction of us considered asexual, dating and mating become a high priority from puberty on. Physiological and psychological influences affect our sexual feelings and behaviors.

The Physiology of Sex

“It is a near-

Science writer Natalie Angier, 2007

Sex is not like hunger, because it is not an actual need. (Without it, we may feel like dying, but we will not.) Yet sex motivates. Had this not been so for all your ancestors, you would not be reading this book. Sexual motivation is nature’s clever way of making people procreate, thus enabling our species’ survival. When two people feel an attraction, they hardly stop to think of themselves as guided by their ancestral genes. As the pleasure we take in eating is nature’s method of getting our body nourishment, so the desires and pleasures of sex are our genes’ way of preserving and spreading themselves. Life is sexually transmitted.

Hormones and Sexual Behavior

11-

Among the forces driving sexual behavior are the sex hormones. The main male sex hormone is testosterone. The main female sex hormones are the estrogens, such as estradiol. Sex hormones influence us at many points in the life span:

- During the prenatal period, they direct our development as males or females.

- During puberty, a sex hormone surge ushers us into adolescence.

- After puberty and well into the late adult years, sex hormones activate sexual behavior.

testosterone the most important of the male sex hormones. Both males and females have it, but the additional testosterone in males stimulates the growth of the male sex organs during the fetal period, and the development of the male sex characteristics during puberty.

estrogens sex hormones, such as estradiol, secreted in greater amounts by females than by males and contributing to female sex characteristics. In nonhuman female mammals, estrogen levels peak during ovulation, promoting sexual receptivity.

In most mammals, nature neatly synchronizes sex with fertility. Females become sexually receptive (in other animals, “in heat”) when their estrogens peak at ovulation. In experiments, researchers can cause female animals to become receptive by injecting them with estrogens. Male hormone levels are more constant, and hormone injection does not so easily manipulate the sexual behavior of male animals (Feder, 1984). Nevertheless, male rats that have had their testes (which manufacture testosterone) surgically removed will gradually lose much of their interest in receptive females. They slowly regain it if injected with testosterone.

434

Hormones do influence human sexual behavior, but in a looser way. Among women with mates, sexual desire rises slightly at ovulation, when there is a surge of estrogens and a smaller surge of testosterone, a change that men can sometimes detect in women’s behaviors and voices (Haselton & Gildersleeve, 2011). One study invited partnered women to keep a diary of their sexual activity. On the days around ovulation, intercourse was 24 percent more frequent (Wilcox et al., 2004).

Women have much less testosterone than men. And more than other mammalian females, women are responsive to their testosterone level (van Anders, 2012). If a woman’s natural testosterone level drops, as happens with removal of the ovaries or adrenal glands, her sexual interest may wane. But as controlled experiments with hundreds of surgically or naturally menopausal women have demonstrated, testosterone-

In human males with abnormally low testosterone levels, testosterone-

Large hormonal surges or declines affect men and women’s desire in shifts that tend to occur at two predictable points in the life span, and sometimes at an unpredictable third point:

- The pubertal surge in sex hormones triggers the development of sex characteristics and sexual interest. If the hormonal surge is precluded—

as it was during the 1600s and 1700s for prepubertal boys who were castrated to preserve their soprano voices for Italian opera— sex characteristics and sexual desire do not develop normally (Peschel & Peschel, 1987). - In later life, estrogen levels fall, and women experience menopause (Chapter 4). As sex hormone levels decline, sex remains a part of life, but the frequency of sexual fantasies and intercourse subsides (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995).

- For some, surgery or drugs may cause hormonal shifts. When adult men were castrated, sex drive typically fell as testosterone levels declined sharply (Hucker & Bain, 1990). Male sex offenders who take Depo-

Provera, a drug that reduces testosterone levels to that of a prepubertal boy, have similarly lost much of their sexual urge (Bilefsky, 2009; Money et al., 1983).

To summarize: We might compare human sex hormones, especially testosterone, to the fuel in a car. Without fuel, a car will not run. But if the fuel level is minimally adequate, adding more fuel to the gas tank won’t change how the car runs. The analogy is imperfect, because hormones and sexual motivation interact. However, it correctly suggests that biology is a necessary but not sufficient explanation of human sexual behavior. The hormonal fuel is essential, but so are the psychological stimuli that turn on the engine, keep it running, and shift it into high gear.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The primary male sex hormone is ______________. The primary female sex hormones are the ______________.

testosterone; estrogens

435

The Sexual Response Cycle

11-

In the 1960s, gynecologist-

- Excitement: The genital areas become engorged with blood, causing a woman’s clitoris and a man’s penis to swell. A woman’s vagina expands and secretes lubricant; her breasts and nipples may enlarge.

- Plateau: Excitement peaks as breathing, pulse, and blood pressure rates continue to increase. A man’s penis becomes fully engorged—

to an average length of 5.6 inches, among 1661 men who measured themselves for condom fitting (Herbenick, 2014). Some fluid— frequently containing enough live sperm to enable conception— may appear at its tip. A woman’s vaginal secretion continues to increase, and her clitoris retracts. Orgasm feels imminent. A nonsmoking 50-

year- old male has about a 1- in- a- million chance of a heart attack during any hour. This increases to merely 2- in- a- million in the two hours during and following sex (with no increase for those who exercise regularly). Compared with risks associated with heavy exertion or anger, this risk seems not worth losing sleep (or sex) over (Jackson, 2009; Muller et al., 1996). - Orgasm: Muscle contractions appear all over the body and are accompanied by further increases in breathing, pulse, and blood pressure rates. A woman’s arousal and orgasm facilitate conception: They help propel semen from the penis, position the uterus to receive sperm, and draw the sperm further inward, increasing retention of deposited sperm (Furlow & Thornhill, 1996). The pleasurable feeling of sexual release apparently is much the same for both sexes. One panel of experts could not reliably distinguish between descriptions of orgasm written by men and those written by women (Vance & Wagner, 1976). In another study, PET scans showed that the same subcortical brain regions were active in men and women during orgasm (Holstege et al., 2003a,b).

- Resolution: The body gradually returns to its unaroused state as the genital blood vessels release their accumulated blood. This happens relatively quickly if orgasm has occurred, relatively slowly otherwise. (It’s like the nasal tickle that goes away rapidly if you have sneezed, slowly otherwise.) Men then enter a refractory period that lasts from a few minutes to a day or more, during which they are incapable of another orgasm. A woman’s much shorter refractory period may enable her, if restimulated during or soon after resolution, to have more orgasms.

sexual response cycle the four stages of sexual responding described by Masters and Johnson—

refractory period a resting period after orgasm, during which a man cannot achieve another orgasm.

sexual dysfunction a problem that consistently impairs sexual arousal or functioning.

erectile disorder inability to develop or maintain an erection due to insufficient bloodflow to the penis.

Sexual Dysfunctions and Paraphilias

female orgasmic disorder distress due to infrequently or never experiencing orgasm.

Masters and Johnson sought not only to describe the human sexual response cycle but also to understand and treat the inability to complete it. Sexual dysfunctions are problems that consistently impair sexual arousal or functioning. Some involve sexual motivation, especially lack of sexual energy and arousability. For men, others include erectile disorder (inability to have or maintain an erection) and premature ejaculation. For women, the problem may be pain or female orgasmic disorder (distress over infrequently or never experiencing orgasm). In separate surveys of some 3000 Boston women and 32,000 other American women, about 4 in 10 reported a sexual problem, such as orgasmic disorder or low desire, but only about 1 in 8 reported that this caused personal distress (Lutfey et al., 2009; Shifren et al., 2008). Most women who have experienced sexual distress have related it to their emotional relationship with the partner during sex (Bancroft et al., 2003).

436

Therapy can help men and women with sexual dysfunctions (Frühauf et al., 2013). In behaviorally oriented therapy, for example, men learn ways to control their urge to ejaculate, and women are trained to bring themselves to orgasm. Starting with the introduction of Viagra in 1998, erectile disorder has been routinely treated by taking a pill. Equally effective drug treatments for female sexual interest/arousal disorder are not yet available.

Sexual dysfunction involves problems with arousal or sexual functioning. People with paraphilias do experience sexual desire, but they direct it in unusual ways. The American Psychiatric Association (2013) only classifies such behavior as disordered if

- a person experiences distress from an unusual sexual interest or

- it entails harm or risk of harm to others.

paraphilias sexual arousal from fantasies, behaviors, or urges involving nonhuman objects, the suffering of self or others, and/or nonconsenting persons.

The serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer had necrophilia, a sexual attraction to corpses. Those with exhibitionism derive pleasure from exposing themselves sexually to others, without consent. People with the paraphilic disorder pedophilia experience sexual arousal toward children who haven’t entered puberty.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

11-

Worldwide, more than 1 million people acquire a sexually transmitted infection (STI; also called STD for sexually transmitted disease) every day (WHO, 2013). Teenage girls, because of their not yet fully mature biological development and lower levels of protective antibodies, are especially vulnerable (Dehne & Riedner, 2005; Guttmacher, 1994). A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study of sexually experienced 14-

AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) a life-

To comprehend the mathematics of infection transmission, imagine this scenario. Over the course of a year, Pat has sex with 9 people, each of whom over the same period has sex with 9 other people, who in turn have sex with 9 others. How many “phantom” sex partners (past partners of partners) will Pat have? The actual number—

Condoms offer only limited protection against certain skin-

Across the available studies, condoms also have been 80 percent effective in preventing transmission of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus—the virus that causes AIDS) from an infected partner (Weller & Davis-

Most Americans with AIDS have been in midlife and younger—

437

Many people assume that oral sex falls in the category of “safe sex,” but recent studies show a significant link between oral sex and transmission of STIs, such as the human papilloma virus (HPV). Risks rise with the number of sexual partners (Gillison et al., 2012). Most HPV infections can now be prevented with a vaccination administered before sexual contact.

Question

hEEHmJjj868NQ+D/Xe/AAuuNP07FA2h0cXUfXlcxOxF571clANuMOdivba+wlvCN3Z1QN+ZGPgx/6tuULveVHXZhJhfZavE74AZfMxX55fL41LsAzP4EsT9cVlpmoGnC/BSVtFxIDKVgRcMatPBD3N3ayfuXPt/Pb8xU09Fe8sD5uEHtjdTBf/f68pd2pwJ5voRvTpphou0lgFTN2aOuZSdj/w6HbR3G8pWmMVCN18PdrahSAPZhKs2wXLc8ttawyT3/JDbomEK0xrRQMJnwAQ==RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The inability to complete the sexual response cycle may be considered a ______________ ______________. Exhibitionism would be considered a ______________.

sexual dysfunction; paraphilia

- From a biological perspective, AIDS is passed more readily from women to men than from men to women. True or false?

False. AIDS is transmitted more easily and more often from men to women.

The Psychology of Sex

11-

Biological factors powerfully influence our sexual motivation and behavior. Yet the wide variations over time, across place, and among individuals document the great influence of psychological factors as well (FIGURE 11.9). Thus, despite the shared biology that underlies sexual motivation, 281 expressed reasons for having sex ranged widely—

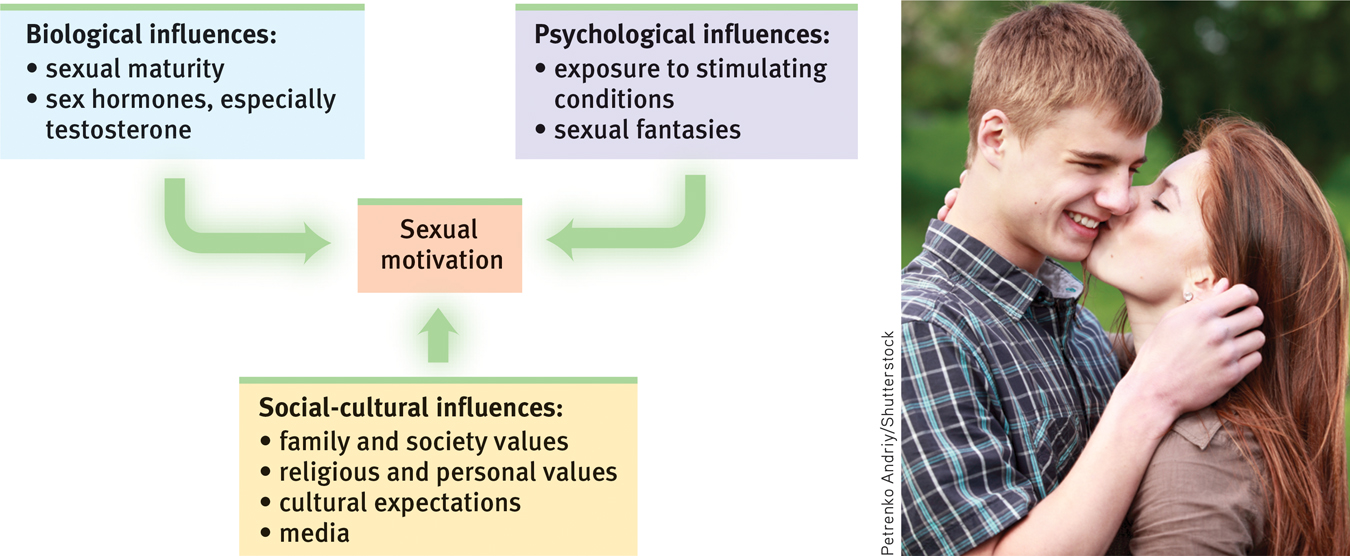

Figure 11.9

Figure 11.9Levels of analysis for sexual motivation Compared with our motivation for eating, our sexual motivation is less influenced by biological factors. Psychological and social-

External Stimuli

Men and women become aroused when they see, hear, or read erotic material (Heiman, 1975; Stockton & Murnen, 1992). In 132 experiments, men’s feelings of sexual arousal have much more closely mirrored their (more obvious) genital response than have women’s (Chivers et al., 2010).

People may find sexual arousal either pleasing or disturbing. (Those who wish to control their arousal often limit their exposure to such materials, just as those wishing to control hunger limit their exposure to tempting cues.) With repeated exposure, the emotional response to any erotic stimulus often lessens, or habituates. During the 1920s, when Western women’s rising hemlines first reached the knee, an exposed leg was a mildly erotic stimulus.

Can exposure to sexually explicit material have adverse effects? Research indicates that it can:

438

- Rape acceptance. Depictions of women being sexually coerced—

and liking it— have increased viewers’ belief in the false idea that women enjoy rape, and have increased male viewers’ willingness to hurt women (Malamuth & Check, 1981; Zillmann, 1989).

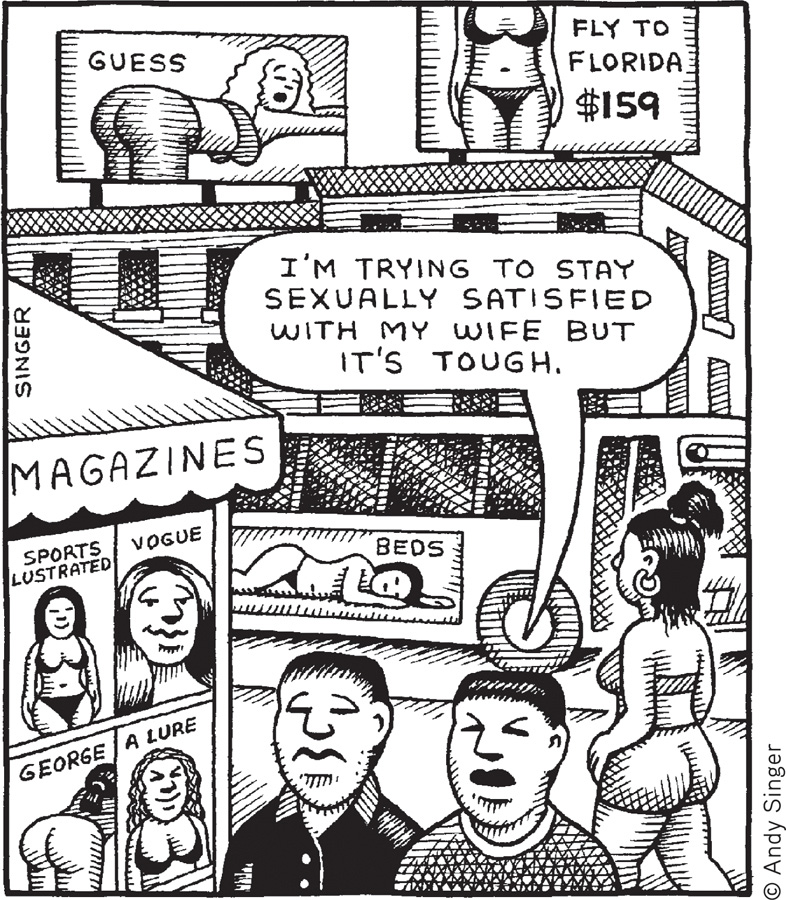

- Devaluing partner. Viewing images of sexually attractive women and men may also lead people to devalue their own partners and relationships. After male collegians viewed TV or magazine depictions of sexually attractive women, they often found an average woman, or their own girlfriend or wife, less attractive (Kenrick & Gutierres, 1980; Kenrick et al., 1989; Weaver et al., 1984).

- Diminished satisfaction. Viewing X-

rated sex films has similarly tended to reduce people’s satisfaction with their own sexual partner (Zillmann, 1989). Reading or watching erotica’s unlikely scenarios may create expectations that few men and women can fulfill.

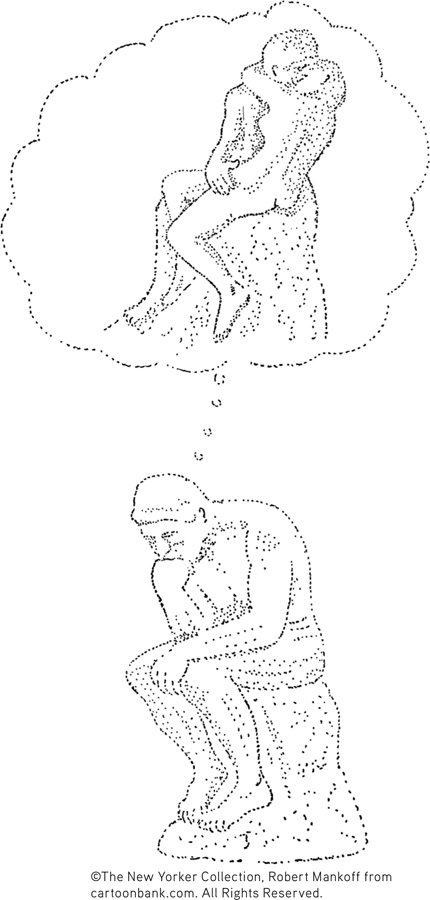

Imagined Stimuli

The brain, it has been said, is our most significant sex organ. The stimuli inside our heads—

Wide-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What factors influence our sexual motivation and behavior?

Influences include biological factors such as sexual maturity and sex hormones, psychological factors such as environmental stimuli and fantasies, and social-

Teen Pregnancy

11-

Sexual attitudes and behaviors vary dramatically across cultures. “Sex between unmarried adults” is “morally unacceptable,” agree 97 percent of Indonesians, 58 percent of Chinese, 30 percent of Americans, and 6 percent of Germans (Pew, 2014). We are all one species, but in some ways how differently we think. Compared with European teens, today’s American teens have a higher pregnancy rate—

So, what produces these variations in teen sexuality and pregnancy? Twin studies show that genes influence teen sexual behavior—

“Condoms should be used on every conceivable occasion.”

Anonymous

Minimal communication about birth control Many teenagers are uncomfortable discussing contraception with their parents, partners, and peers. Teens who talk freely with parents, and who are in an exclusive relationship with a partner with whom they communicate openly, are more likely to use contraceptives (Aspy et al., 2007; Milan & Kilmann, 1987).

Guilt related to sexual activity In another survey, 72 percent of sexually active 12-

439

Alcohol use Most sexual hook-

Mass media norms of unprotected promiscuity Media help write the “social scripts” that affect our perceptions and actions. So what sexual scripts do today’s media write on our minds? Sexual content appears in approximately 85 percent of movies, 82 percent of television programs, 59 percent of music videos, and 37 percent of music lyrics (Ward et al., 2014). And sexual partners on TV shows rarely have communicated any concern for birth control or STIs (Brown et al., 2002; Kunkel, 2001; Sapolski & Tabarlet, 1991). The more sexual content adolescents and young adults view or read (even when controlling for other predictors of early sexual activity), the more likely they are to perceive their peers as sexually active, to develop sexually permissive attitudes, and to experience early intercourse (Escobar-

Media influences can either increase or decrease sexual risk taking. One study asked more than a thousand 12-

Later sex may pay emotional dividends. One national study followed participants to about age 30. Even after controlling for several other factors, those who had later first sex reported greater relationship satisfaction in their marriages and partnerships (Harden, 2012). Several other factors also predict sexual restraint:

- High intelligence Teens with high rather than average intelligence test scores more often delayed sex, partly because they appreciated possible negative consequences and were more focused on future achievement than on here-

and- now pleasures (Halpern et al., 2000). - Religious engagement Actively religious teens have more often reserved sexual activity for adulthood (Hull et al., 2011; Lucero et al., 2008).

- Father presence In studies that followed hundreds of New Zealand and U.S. girls from age 5 to 18, a father’s absence was linked to sexual activity before age 16 and to teen pregnancy (Ellis et al., 2003). These associations held even after adjusting for other adverse influences, such as poverty. Close family attachments—

families that eat together and where parents know their teens’ activities and friends— also predicted later sexual initiation (Coley et al., 2008). - Participation in service learning programs Several experiments have found that teens volunteering as tutors or teachers’ aides, or participating in community projects, had lower pregnancy rates than were found among comparable teens randomly assigned to control conditions (Kirby, 2002; O’Donnell et al., 2002). Researchers are unsure why. Does service learning promote a sense of personal competence, control, and responsibility? Does it encourage more future-

oriented thinking? Or does it simply reduce opportunities for unprotected sex?

440

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which THREE of the following five factors contribute to unplanned teen pregnancies?

- Alcohol use

- Higher intelligence level

- Unprotected sex

- Mass media models

- Increased communication about options

a., c., d.

Sexual Orientation

sexual orientation an enduring sexual attraction toward members of one’s own sex (homosexual orientation), the other sex (heterosexual orientation), or both sexes (bisexual orientation).

11-

In one British survey, of the 18,876 people contacted, 1 percent were asexual, having “never felt sexually attracted to anyone at all” (Bogaert, 2004, 2006b; 2012). People identifying as asexual are, however, nearly as likely as others to report masturbating, noting that it feels good, reduces anxiety, or “cleans out the plumbing.”

To motivate is to energize and direct behavior. So far, we have considered the energizing of sexual motivation but not its direction, which is our sexual orientation—our enduring sexual attraction toward members of our own sex (homosexual orientation), the other sex (heterosexual orientation), or both sexes (bisexual orientation). We experience this attraction in our interests, thoughts, and fantasies (who’s that person in your imagination?). Cultures vary in their attitudes toward same-

Sexual Orientation: The Numbers

How many people are exclusively homosexual? About 10 percent, as the popular press has often assumed? Or 20 percent, as the average American estimated in a 2013 survey (Jones et al., 2014)? According to more than a dozen national surveys that have explored sexual orientation in Europe and the United States, a better estimate is about 3 or 4 percent of men and 2 percent of women (Chandra et al., 2011; Herbenick et al., 2010a; Savin-

Survey methods that absolutely guarantee people’s anonymity reveal another percent or two of gay people (Coffman et al., 2013). Moreover, people in less tolerant places are more likely to hide their sexual orientation. About 3 percent of California men express a same-

Fewer than 1 percent of people—

441

What does it feel like to be homosexual in a heterosexual culture? If you are heterosexual, one way to understand is to imagine how you would feel if you were socially isolated for openly admitting or displaying your feelings toward someone of the other sex. How would you react if you overheard people making crude jokes about heterosexual people, or if most movies, TV shows, and advertisements portrayed (or implied) homosexuality? And how would you answer if your family members were pleading with you to change your heterosexual lifestyle and to enter into a homosexual marriage?

Facing such reactions, some individuals struggle with their sexual attractions, especially during adolescence and if feeling rejected by parents or harassed by peers. If lacking social support, the result may be lower self-

Today’s psychologists therefore view sexual orientation as neither willfully chosen nor willfully changed. “Efforts to change sexual orientation are unlikely to be successful and involve some risk of harm,” declared a 2009 American Psychological Association report. Sexual orientation in some ways is like handedness: Most people are one way, some the other. A very few are truly ambidextrous. Regardless, the way one is endures.

This conclusion is most strongly established for men. Women’s sexual orientation tends to be less strongly felt and potentially more fluid and changing (Chivers, 2005; Diamond, 2008; Dickson et al., 2013). In general, men are sexually simpler. Their lesser sexual variability is apparent in many ways, notes Roy Baumeister (2000). Across time, across cultures, across situations, and across differing levels of education, religious observance, and peer influence, adult women’s sexual drive and interests are more flexible and varying than are adult men’s. Women, for example, more often prefer to alternate periods of high sexual activity with periods of almost none (Mosher et al., 2005). In their pupil dilation and genital responses to erotic videos, and in their implicit attitudes, heterosexual women exhibit more bisexual attraction than do men (Rieger & Savin-

In men, a high sex drive is associated with increased attraction to women (if heterosexual), or men (if homosexual). In women, a high sex drive is generally associated with increased attraction to both men and women (Lippa, 2006, 2007a; Lippa et al., 2010). When shown sexually explicit film clips, men’s genital and subjective sexual arousal is mostly to preferred sexual stimuli (for heterosexual viewers, depictions of women). Women respond more nonspecifically to depictions of sexual activity involving males or females (Chivers et al., 2007).

Is there truth to the homosexual-

442

Note that the scientific question is not “What causes homosexuality?” (or “What causes heterosexuality?”) but “What causes differing sexual orientations?” In pursuit of answers, psychological science compares the backgrounds and physiology of people whose sexual orientations differ.

Origins of Sexual Orientation

So, our sexual orientation is something we do not choose and (especially for males) cannot change. Where, then, do these preferences come from? See if you can anticipate the conclusions that have emerged from hundreds of research studies by responding Yes or No to the following questions:

- Is homosexuality linked with problems in a child’s relationships with parents, such as with a domineering mother and an ineffectual father, or a possessive mother and a hostile father?

- Does homosexuality involve a fear or hatred of people of the other sex, leading individuals to direct their desires toward members of their own sex?

- Is sexual orientation linked with levels of sex hormones currently in the blood?

- As children, were most homosexuals molested, seduced, or otherwise sexually victimized by an adult homosexual?

The answer to all these questions has been No (Storms, 1983). In a search for possible environmental influences on sexual orientation, Kinsey Institute investigators interviewed nearly 1000 homosexuals and 500 heterosexuals. They assessed nearly every imaginable psychological cause of homosexuality—

And consider this: If “distant fathers” were more likely to produce homosexual sons, then shouldn’t boys growing up in father-

So, what else might influence sexual orientation? One theory has proposed that people develop same-

The bottom line from a half-

Same-

443

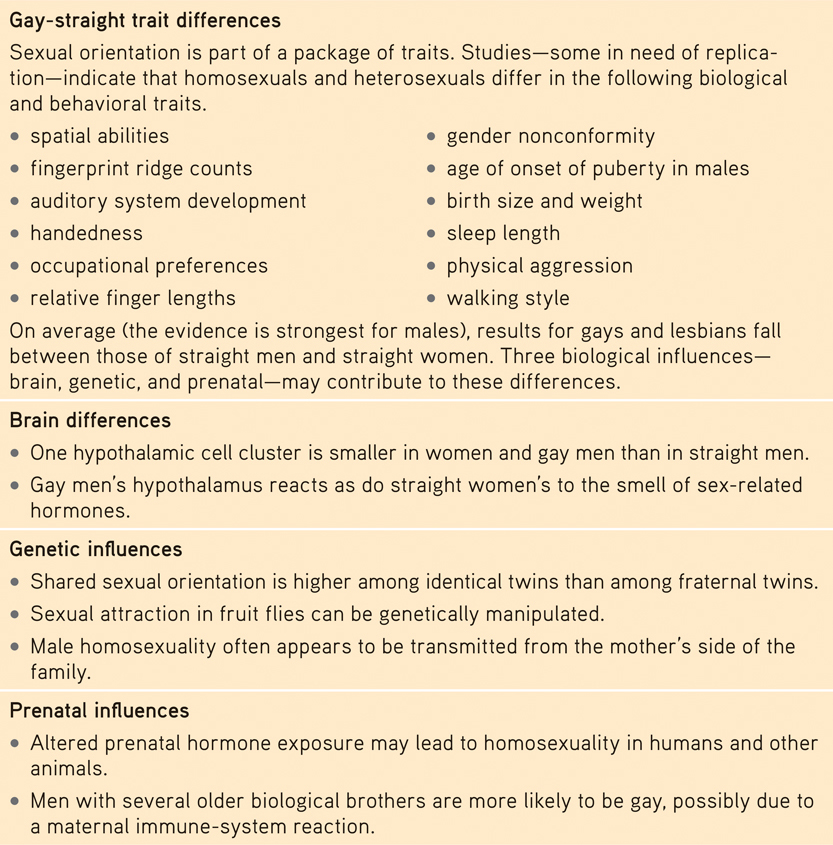

Gay-

It should not surprise us that in other ways, too, brains differ with sexual orientation (Bao & Swaab, 2011; Savic & Lindström, 2008). Remember our maxim: Everything psychological is simultaneously biological. But when do such brain differences begin? At conception? In the womb? During childhood or adolescence? Does experience produce these differences? Or is it genes or prenatal hormones (or genes via prenatal hormones)?

LeVay does not view the hypothalamus as a sexual orientation center; rather, he sees it as an important part of the neural pathway engaged in sexual behavior. He acknowledges that sexual behavior patterns may influence the brain’s anatomy. In fish, birds, rats, and humans, brain structures vary with experience—

“Gay men simply don’t have the brain cells to be attracted to women.”

Simon LeVay, The Sexual Brain, 1993

Responses to hormone-

Genetic Influences Evidence indicates a genetic influence on sexual orientation. “First, homosexuality does appear to run in families,” noted Brian Mustanski and Michael Bailey (2003). “Second, twin studies have established that genes play a substantial role in explaining individual differences in sexual orientation.” Identical twins are somewhat more likely than fraternal twins to share a homosexual orientation (Alanko et al., 2010; Lángström et al., 2008, 2010). (Because sexual orientations differ in many identical twin pairs, especially female twins, we know that other factors besides genes are also at work.)

By genetic manipulations, experimenters have created female fruit flies that during courtship act like males (pursuing other females) and males that act like females (Demir & Dickson, 2005). “We have shown that a single gene in the fruit fly is sufficient to determine all aspects of the flies’ sexual orientation and behavior,” explained Barry Dickson (2005). With humans, it’s likely that multiple genes, possibly in interaction with other influences, shape sexual orientation. A genome-

444

Researchers have speculated about possible reasons why “gay genes” might exist in the human gene pool, given that same-

A fertile females theory offers further support for the idea that maternal genetics may be at work (Bocklandt et al., 2006). Recent Italian studies confirm what others have found—

Prenatal Influences Elevated rates of homosexual orientation in identical and fraternal twins suggest the influence not only of shared genes but also a shared prenatal environment. In animals and some human cases, prenatal hormone conditions have altered a fetus’ sexual orientation. German researcher Gunter Dorner (1976, 1988) pioneered research on the influence of prenatal hormones by manipulating a fetal rat’s exposure to male hormones, thereby “inverting” its sexual orientation. In other studies, when pregnant sheep were injected with testosterone during a critical period of fetal development, their female offspring later showed homosexual behavior (Money, 1987).

“Modern scientific research indicates that sexual orientation is … partly determined by genetics, but more specifically by hormonal activity in the womb.”

Glenn Wilson and Qazi Rahman, Born Gay: The Psychobiology of Sex Orientation, 2005

A critical period for the human brain’s neural-

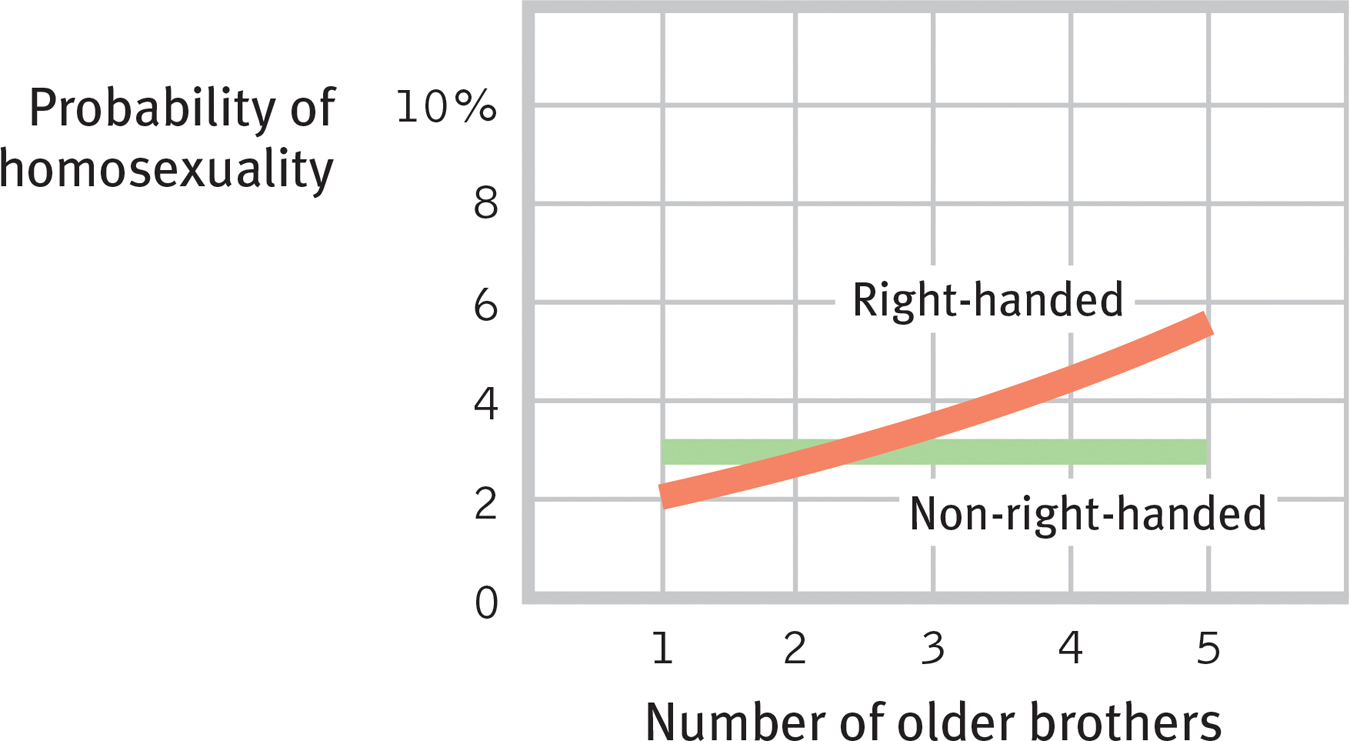

The mother’s immune system may also play a role in the development of sexual orientation. Men who have older brothers are somewhat more likely to be gay, report Ray Blanchard (2004, 2008a,b, 2014) and Anthony Bogaert (2003)—about one-

Figure 11.10

Figure 11.10The fraternal birth-

445

Gay-

On several traits, gays and lesbians appear to fall midway between straight females and males (TABLE 11.2; see also LeVay, 2011; Rahman & Koerting, 2008). For example, lesbians’ cochlea and hearing systems develop in a way that is intermediate between those of heterosexual females and heterosexual males, which seems attributable to prenatal hormonal influence (McFadden, 2002). Gay men tend to be shorter and lighter, even at birth, than straight men, while women in same-

TABLE 11.2

TABLE 11.2Biological Correlates of Sexual Orientation

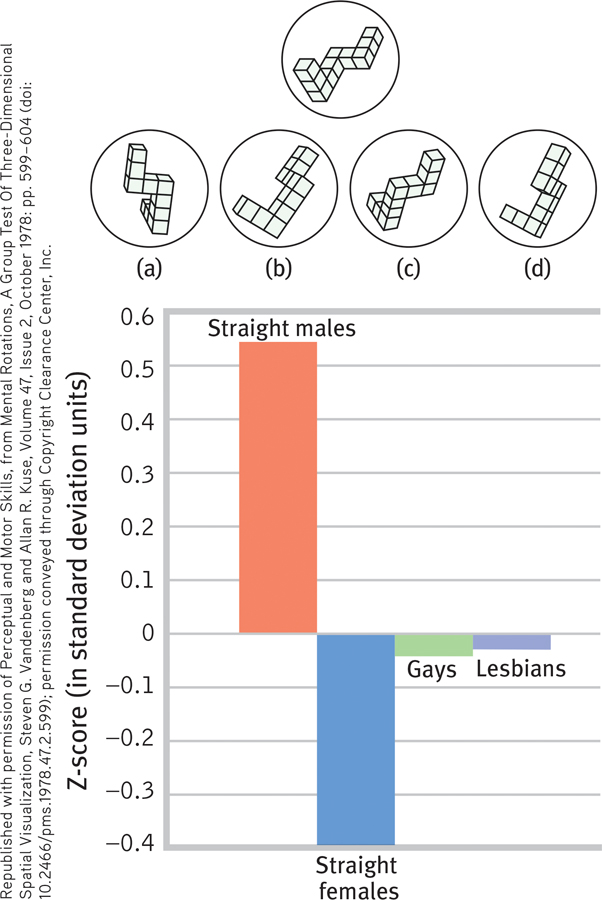

For an 8-

For an 8-

446

Another you-

Figure 11.11

Figure 11.11Spatial abilities and sexual orientation

Which of the four figures can be rotated to match the target figure at the top? Straight males tend to find this an easier task than do straight females, with gays and lesbians intermediate. (From Rahman et al., 2003, with 60 people tested in each group.)

Answer: Figures a and d.

***

The consistency of the brain, genetic, and prenatal findings has swung the pendulum toward a biological explanation of sexual orientation (Rahman & Wilson, 2003; Rahman & Koerting, 2008). Still, some people wonder: Should the cause of sexual orientation matter? Perhaps it shouldn’t, but people’s assumptions matter. To justify his signing a 2014 bill that made some homosexual acts punishable by life in prison, the president of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni, declared that homosexuality is not inborn but rather is a matter of “choice” (Balter, 2014; Landau et al., 2014).

“There is no sound scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed.”

UK Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2009

However, the new biological research is a double-

Question

P+i1u/QBChwN3g13Rn9HQ6OdeYMsnZVXVQNnPQNspjhHGMFIqRo06rQwaA7++ZhywPXYvG1zRzNU/GygY1NZODlHXBibB7TLV3bmqcwRAb7pHZUeZKVq0hes8h+1V+w7F/PH+GK0kass0PS8Tf9aC9C0CBYhGpXiGM6U0lsA79ostEnqcgGL8XVIj4DqJnna/kgmwf9dFFzPHlPISrMkNN8Kz7rNT1ygNrsORtRpXAd2UPFInMXaguas0BxZ3NzUdFRUapFuhOktzc3ahfI600YHiLLGw3qAZnrAcgGD+AA1MaKd4i0i2S0fr7O9O0IxodXwBjV0z+E7k1V3+giWzIYDCs9kn0TdTflMee1JrD0DXpM9nMZBfA==RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which THREE of the following five factors have researchers found to have an effect on sexual orientation?

|

a. A domineering mother b. Size of certain cell clusters c. Prenatal hormone exposure |

d. A distant or ineffectual father e. For men, having multiple older |

b., c., e.

Sex and Human Values

11-

Recognizing that values are both personal and cultural, most sex researchers and educators strive to keep their writings value free. But the very words we use to describe behavior can reflect our personal values. Whether we label certain sexual behaviors as “perversions” or as an “alternative sexual lifestyle” depends on our attitude toward the behaviors. Labels describe, but they also evaluate.

Scientific research on sexual motivation does not aim to define the personal meaning of sex in our own lives. You could know every available fact about sex—

447

Surely one significance of such intimacy is its expression of our profoundly social nature. One recent study asked 2035 married people when they started having sex (while controlling for education, religious engagement, and relationship length). Those whose relationship first developed to a deep commitment, such as marriage, not only reported greater relationship satisfaction and stability but also better sex (Busby et al., 2010; Galinsky & Sonenstein, 2013). For both men and women, but especially for women, orgasm occurs more often (and with less morning-

The benefits of commitment—

Sex is a socially significant act. Men and women can achieve orgasm alone, yet most people find greater satisfaction—