12.2 Expressing Emotion

“Your face, my thane, is a book where men may read strange matters.”

Lady Macbeth to her husband, in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth

Expressive behavior implies emotion. Dolphins, with smiles seemingly plastered on their faces, appear happy. To decipher people’s emotions we read their bodies, listen to their voice tones, and study their faces. Does nonverbal language vary with culture—

Detecting Emotion in Others

12-

To Westerners, a firm handshake conveys an outgoing, expressive personality (Chaplin et al., 2000). A gaze, an averted glance, or a stare communicates intimacy, submission, or dominance (Kleinke, 1986). Darting eyes and swiveled heads signal anxiety (Perkins et al., 2012). When two people are passionately in love, they typically spend time—

Most of us read nonverbal cues well. Shown 10 seconds of video from the end of a speed-

469

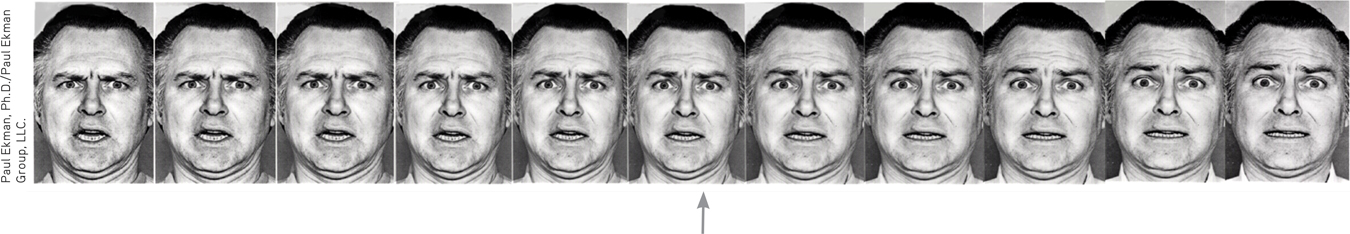

Experience can sensitize us to particular emotions, as shown by experiments using a series of faces (like those in FIGURE 12.6) that morph from anger to fear (or sadness). Viewing such faces, physically abused children are much quicker than other children to spot the signals of anger. Shown a face that is 50 percent fear and 50 percent anger, they are more likely to perceive anger than fear. Their perceptions become sensitively attuned to glimmers of danger that nonabused children miss.

Figure 12.6

Figure 12.6Experience influences how we perceive emotions Viewing the morphed middle face, evenly mixing fear with anger, physically abused children were more likely than nonabused children to perceive the face as angry (Pollak & Kistler, 2002; Pollak & Tolley-

Hard-

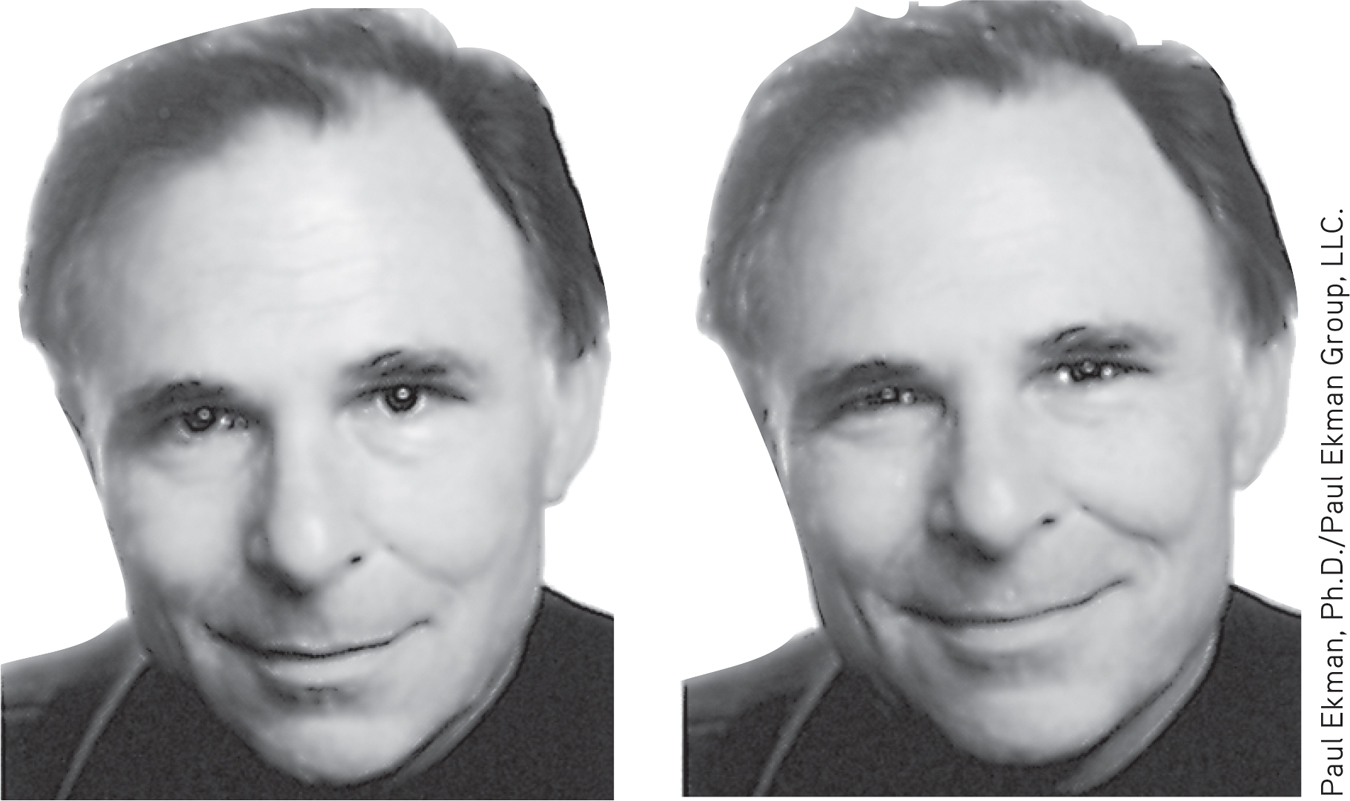

Figure 12.7

Figure 12.7Which of researcher Paul Ekman’s smiles is feigned, which natural? The smile on the right engages the facial muscles of a natural smile.

Our brain is an amazing detector of subtle expressions. When researchers filmed teachers talking to unseen schoolchildren, a mere 10-

Despite our brain’s emotion-

Some of us are more sensitive than others to physical cues to various emotions. In one study, hundreds of people were asked to name the emotion displayed in brief film clips. The clips showed portions of a person’s emotionally expressive face or body, sometimes accompanied by a garbled voice (Rosenthal et al., 1979). For example, after a 2-

470

Gestures, facial expressions, and voice tones, which are absent in written communication, convey important information. The difference was clear in one study. In one group, participants heard 30-

The absence of expressive emotion can make for ambiguous emotion in electronic communications. To partly remedy that, we sometimes embed visual cues to emotion (ROFL!) in our texts, e-

Question

9CWxKszH/wjncMFgPe6+fDd3QKeJ5eL8agNbwPv1dbgb1Er0nNTFDUKXe6fM2gOLHi9EWSlcJi1YyEgjEEvW3lwq3/bH6mM6oZ8mwcC5U/cXONz7Zo5s9yR3V/3ZH/I4bDndkpVFP+rebuc48bnCR/lxe/u9CWlfWS+AhPIlh6szab9DONGO73r2W1MS2ETlVCxJ5ICKjnQW0pC4t83sh9aLeo1EOrt2Euo+SSB7PquuG7SXzsT09eWtPQbe+M5mGender, Emotion, and Nonverbal Behavior

12-

Is women’s intuition, as so many believe, superior to men’s? After analyzing 125 studies of sensitivity to nonverbal cues, Judith Hall (1984, 1987) concluded that women generally do surpass men at reading people’s emotional cues when given thin slices of behavior. The female advantage emerges early in development. In one analysis of 107 study findings, female infants, children, and adolescents outperformed males (McClure, 2000).

Women’s nonverbal sensitivity helps explain their greater emotional literacy. When invited to describe how they would feel in certain situations, men described simpler emotional reactions (Barrett et al., 2000). You might like to try this yourself: Ask some people how they might feel when saying good-

Women’s skill at decoding others’ emotions may also contribute to their greater emotional responsiveness (Vigil, 2009). In studies of 23,000 people from 26 cultures, women more than men reported themselves open to feelings (Costa et al., 2001). Children show the same gender difference: Girls express stronger emotions than boys do (Chaplin & Aldao, 2013). That helps explain the extremely strong perception that emotionality is “more true of women”—a perception expressed by nearly 100 percent of 18-

One exception: Quickly—

Figure 12.8

Figure 12.8Male or female? Researchers manipulated a gender-

471

The perception of women’s emotionality also feeds—

Females are also more likely to express empathy—

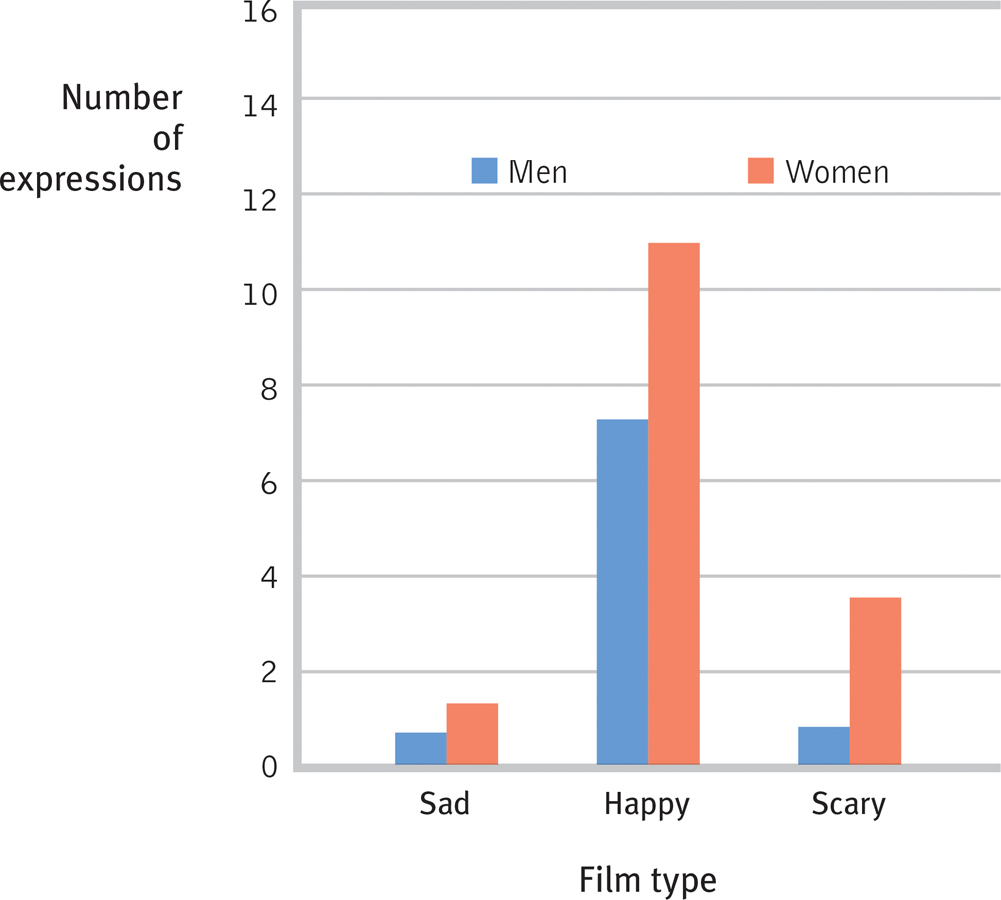

Figure 12.9

Figure 12.9Gender and expressiveness Male and female film viewers did not differ dramatically in self-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- ______________ (Women/Men) report experiencing emotions more deeply, and they tend to be more adept at reading nonverbal behavior.

Women

Culture and Emotional Expression

12-

The meaning of gestures varies with the culture. U.S. President Richard Nixon learned this after making the North American “A-

472

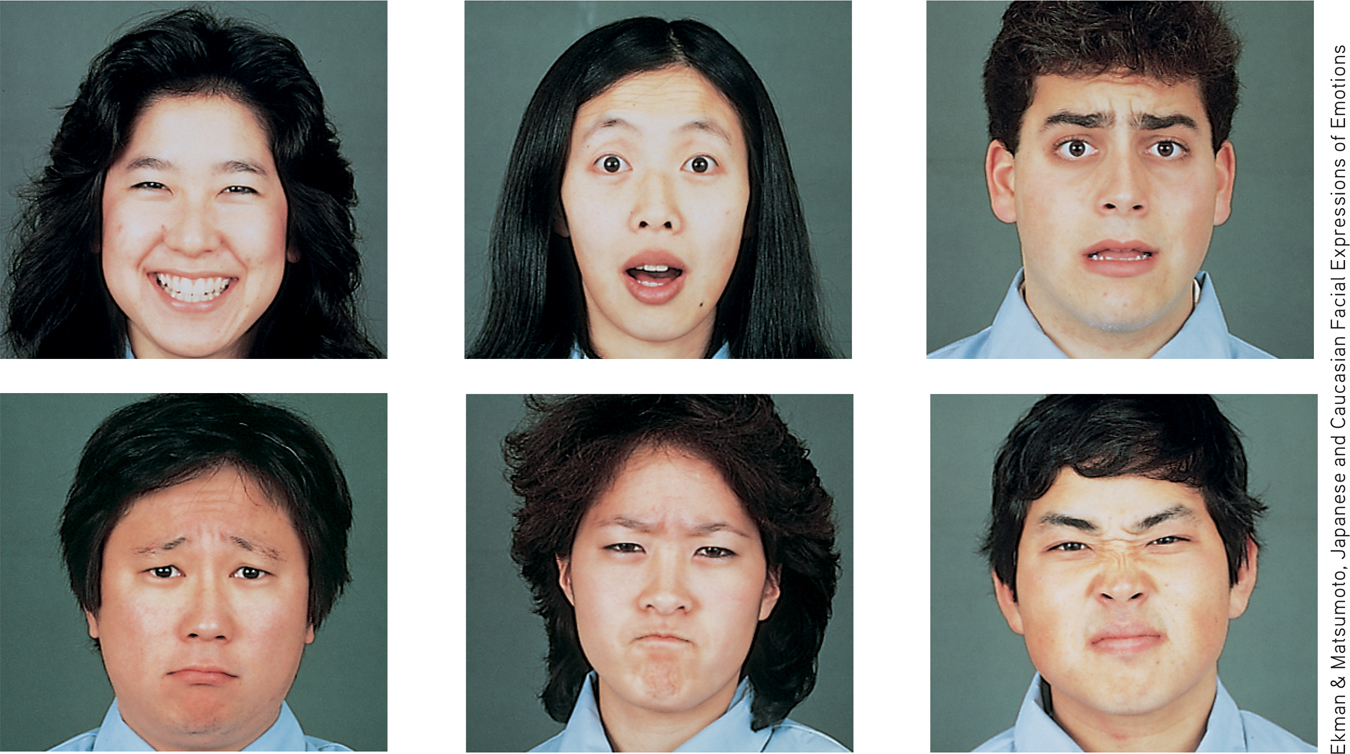

Do facial expressions also have different meanings in different cultures? To find out, two investigative teams showed photographs of various facial expressions to people in different parts of the world and asked them to guess the emotion (Ekman et al., 1975, 1987, 1994; Izard, 1977, 1994). You can try this matching task yourself by pairing the six emotions with the six faces in FIGURE 12.10.

Figure 12.10

Figure 12.10Culture-

As people of differing cultures and races, do our faces speak differing languages? Which face expresses disgust? Anger? Fear? Happiness? Sadness? Surprise? (From Matsumoto & Ekman, 1989.) See answers below.

From left to right, top to bottom: happiness, surprise, fear, sadness, anger, disgust.

Regardless of your cultural background, you probably did pretty well. A smile’s a smile the world around. Ditto for sadness, and to a lesser extent the other basic expressions (Jack et al., 2012). (There is no culture where people frown when they are happy.)

Facial expressions do convey some nonverbal accents that provide clues to one’s culture (Marsh et al., 2003). Thus, data from 182 studies have shown slightly enhanced accuracy when people judged emotions from their own culture (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002, 2003a,b). Still, the telltale signs of emotion generally cross cultures. The world over, children cry when distressed, shake their heads when defiant, and smile when they are happy. So, too, with blind children who have never seen a face (Eibl-

Musical expressions of emotion also cross cultures. Happy and sad music feels happy and sad around the world. Whether you live in an African village or a European city, fast-

Do these shared emotional categories reflect shared cultural experiences, such as movies and TV broadcasts seen around the world? Apparently not. Paul Ekman and his team asked isolated people in New Guinea to respond to such statements as, “Pretend your child has died.” When North American collegians viewed the taped responses, they easily read the New Guineans’ facial reactions.

473

“For news of the heart, ask the face.”

Guinean proverb

So we can say that facial muscles speak a universal language. This discovery would not have surprised Charles Darwin (1809–

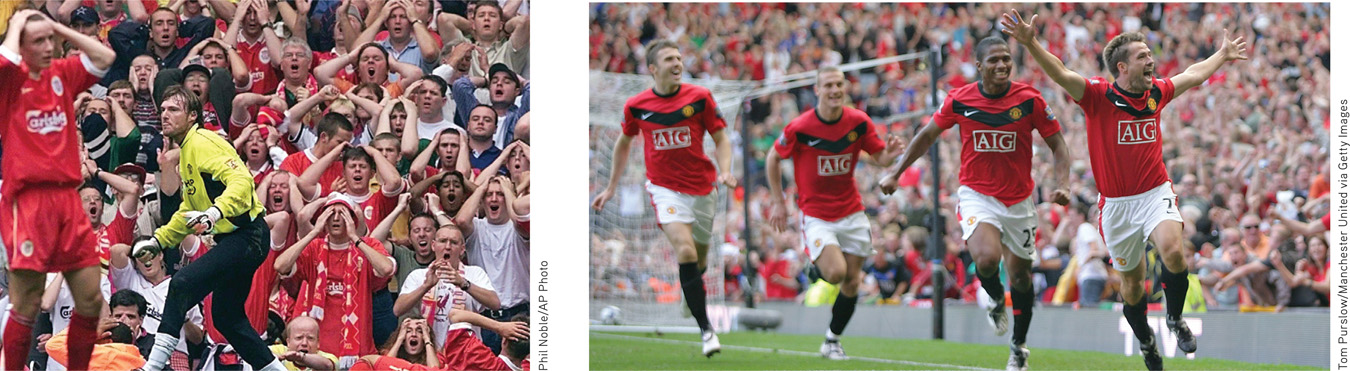

Smiles are social as well as emotional events. Euphoric Olympic gold-

For a 4-

For a 4-

While weightless, astronauts’ internal bodily fluids move toward their upper body and their faces become puffy. This makes nonverbal communication more difficult, especially among multinational crews (Gelman, 1989).

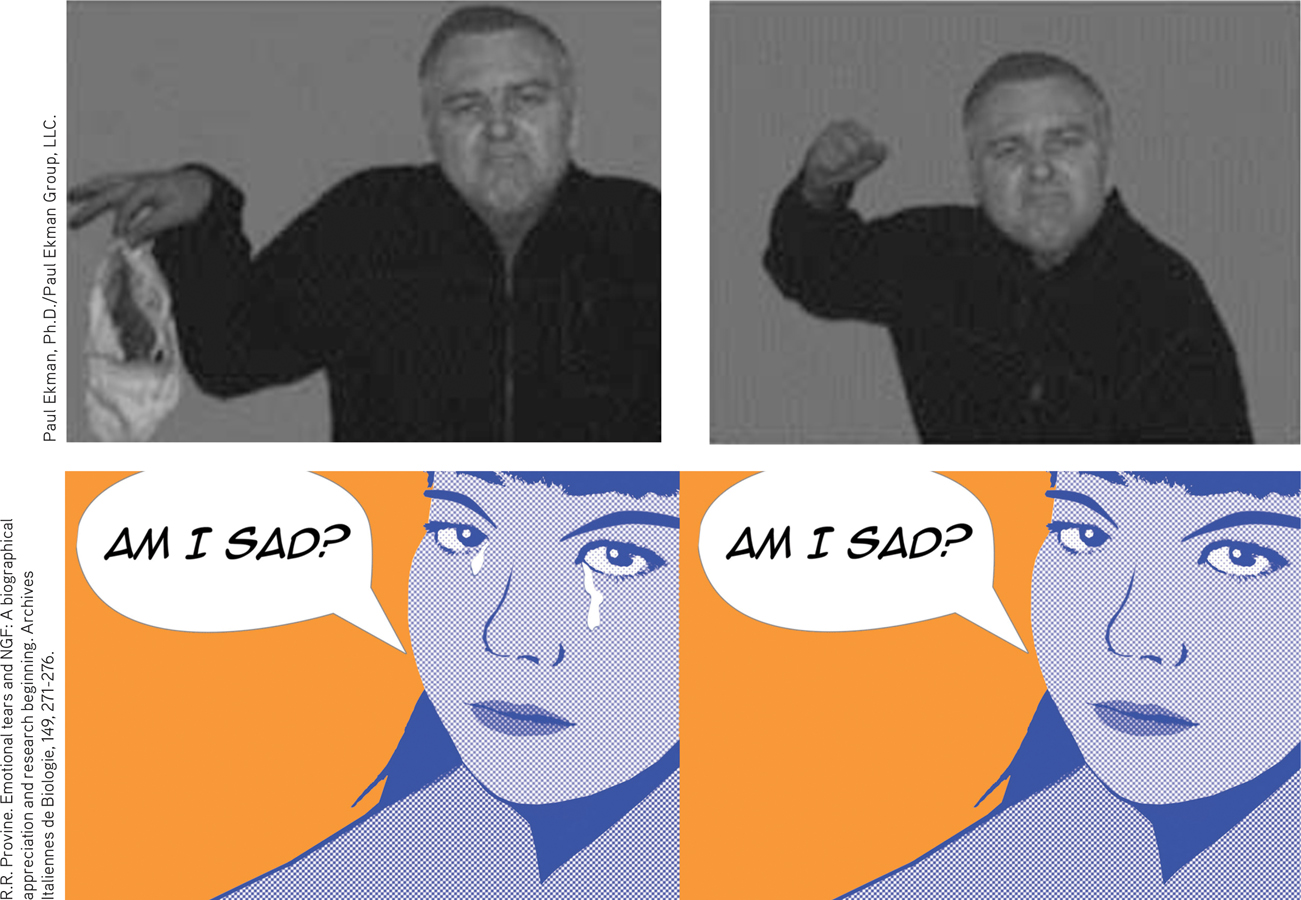

Although we share a universal facial language, it has been adaptive for us to interpret faces in particular contexts (FIGURE 12.11). People judge an angry face set in a frightening situation as afraid. They judge a fearful face set in a painful situation as pained (Carroll & Russell, 1996). Movie directors harness this phenomenon by creating contexts and soundtracks that amplify our perceptions of particular emotions.

Figure 12.11

Figure 12.11We read faces in context Whether we perceive the man in the top row as disgusted or angry depends on which body his face appears on (Aviezer et al., 2008). In the second row, tears on a face make its expression seem sadder (Provine et al., 2009).

Although cultures share a universal facial language for some basic emotions, they differ in how much emotion they express. Those that encourage individuality, as in Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America, display mostly visible emotions (van Hemert et al., 2007). Those that encourage people to adjust to others, as in China, tend to have less visible displays of personal emotions (Matsumoto et al., 2009b; Tsai et al., 2007). In Japan, people infer emotion more from the surrounding context. Moreover, the mouth, which is so expressive in North Americans, conveys less emotion than do the telltale eyes (Masuda et al., 2008; Yuki et al., 2007).

474

Cultural differences also exist within nations. The Irish and their Irish-

Question

A0ikqe2bRuIWRoC69/cIqnx1GaldoKCrhCmfTOTV/reibKqsuRhmuK3G1dmL7WPS+fSiU10XIiAHqqrotWLaAwd739EwPtmMYbkCNPyF//zrm6Xi+qieycYNcBqleLvPxiyd/DsT6QYv2bANkfbfTHDEGPhsxb670cf6dLUYzG87bs4Z4St6dIO1xymp3Qek5jJiao6tyZjZu0LLCX632OS7LIk2rtYinDN8qlCaEwNGfC3+33aJRjAbJQ06ThG6ywp48SCgsrY=RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Are people in different cultures more likely to differ in their interpretations of facial expressions or of gestures?

gestures

The Effects of Facial Expressions

12-

As William James (1890) struggled with feelings of depression and grief, he came to believe that we can control emotions by going “through the outward movements” of any emotion we want to experience. “To feel cheerful,” he advised, “sit up cheerfully, look around cheerfully, and act as if cheerfulness were already there.”

“Whenever I feel afraid I hold my head erect And whistle a happy tune.”

Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, The King and I, 1958

facial feedback effect the tendency of facial muscle states to trigger corresponding feelings such as fear, anger, or happiness.

Studies of emotional effects of facial expressions reveal precisely what James might have predicted. Expressions not only communicate emotion, they also amplify and regulate it. In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin (1872) contended that “the free expression by outward signs of an emotion intensifies it.… He who gives way to violent gestures will increase his rage.”

Was Darwin right? You can test his hypothesis: Fake a big grin. Now scowl. Can you feel the “smile therapy” difference? Participants in dozens of experiments have felt a difference. James Laird and his colleagues (1974, 1984, 1989) subtly induced students to make a frowning expression by asking them to “contract these muscles” and “pull your brows together” (supposedly to help the researchers attach facial electrodes). The results? The students reported feeling a little angry, and they similarly adopted other basic emotions. For example, people reported feeling more fear than anger, disgust, or sadness when made to construct a fearful expression: “Raise your eyebrows. And open your eyes wide. Move your whole head back, so that your chin is tucked in a little bit, and let your mouth relax and hang open a little” (Duclos et al., 1989).

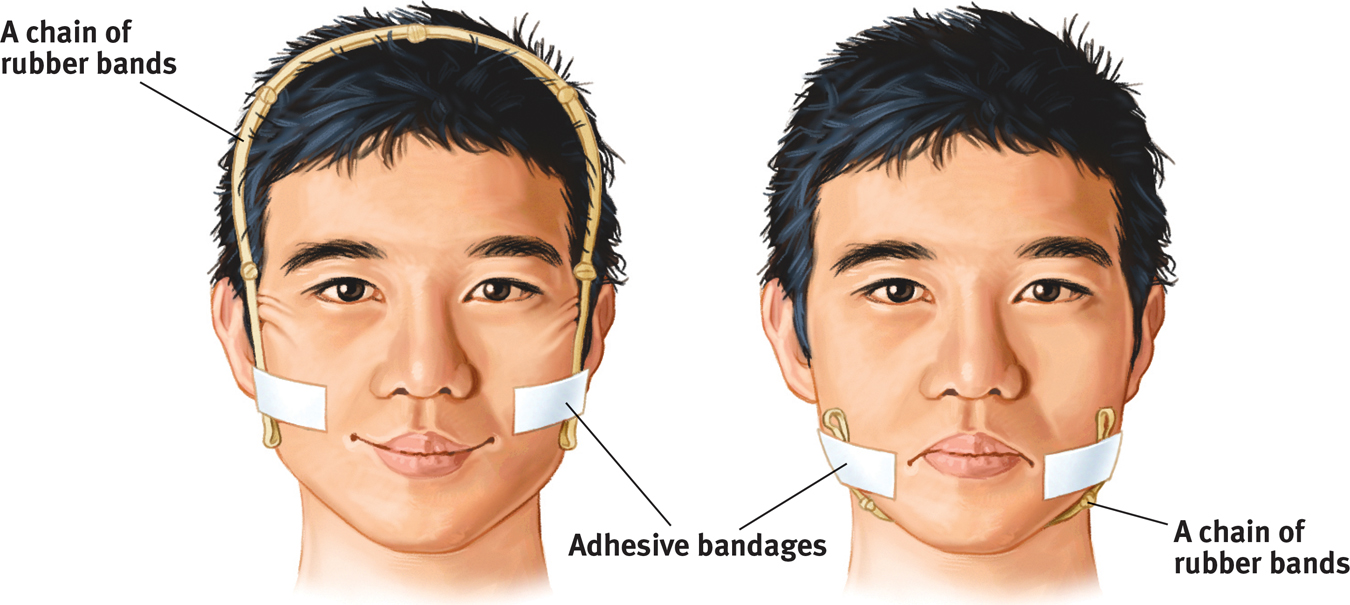

This facial feedback effect has been found many times, in many places, for many basic emotions (FIGURE 12.12). Just activating one of the smiling muscles by holding a pen in the teeth (rather than gently in the mouth, which produces a neutral expression) makes stressful situations less upsetting (Kraft & Pressman, 2012). A heartier smile—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

Figure 12.12

Figure 12.12How to make people smile without telling them to smile

- Do as Kazuo Mori and Hideko Mori (2009) did with students in Japan: Attach rubber bands to the sides of the face with adhesive bandages, and then run them either over the head or under the chin. (1) Based on the facial feedback effect, how might students report feeling when the rubber bands raise their cheeks as though in a smile? (2) How might students report feeling when the rubber bands pull their cheeks downward?

(1) Most students report feeling more happy than sad when their cheeks are raised upward. (2) Most students report feeling more sad than happy when their cheeks are pulled downward.

A request from your authors: Smile often as you read this book.

behavior feedback effect the tendency of behavior to influence our own and others’ thoughts, feelings, and actions.

So your face is more than a billboard that displays your feelings; it also feeds your feelings. No wonder people feel less depressed after Botox injections that paralyze the frowning muscles (Wollmer et al., 2012). Four months after treatment, people continued to report lower depression levels. Follow-

Other researchers have observed a similar behavior feedback effect (Flack, 2006; Snodgrass et al., 1986). You can duplicate the participants’ experience: Walk for a few minutes with short, shuffling steps, keeping your eyes downcast. Now walk around taking long strides, with your arms swinging and your eyes looking straight ahead. Can you feel your mood shift? Going through the motions awakens the emotions.

475

Likewise, people perceive ambiguous behaviors differently depending on which finger they move up and down while reading a story. (This was said to be a study of the effect of using finger muscles “located near the reading muscles on the motor cortex.”) If participants read the story while moving an extended middle finger, the story behaviors seemed more hostile. If read with a thumb up, they seemed more positive. Hostile gestures prime hostile perceptions (Chandler & Schwarz, 2009; Goldin-

You can use your understanding of feedback effects to become more empathic: Let your own face mimic another person’s expression. Acting as another acts helps us feel what another feels (Vaughn & Lanzetta, 1981). Indeed, natural mimicry of others’ emotions helps explain why emotions are contagious (Dimberg et al., 2000; Neumann & Strack, 2000). Positive, upbeat Facebook posts create a ripple effect, leading Facebook friends to also express more positive emotions (Kramer, 2012). Primates also ape one another, and their synchronized expressions help bond them (and us) together (de Waal, 2009). Losing this ability to mimic others can leave us struggling to make emotional connections, as one social worker with Moebius syndrome, a rare facial paralysis disorder, discovered while working with Hurricane Katrina refugees: When people made a sad expression, “I wasn’t able to return it. I tried to do so with words and tone of voice, but it was no use. Stripped of the facial expression, the emotion just dies there, unshared” (Carey, 2010).