12.3 Experiencing Emotion

12-

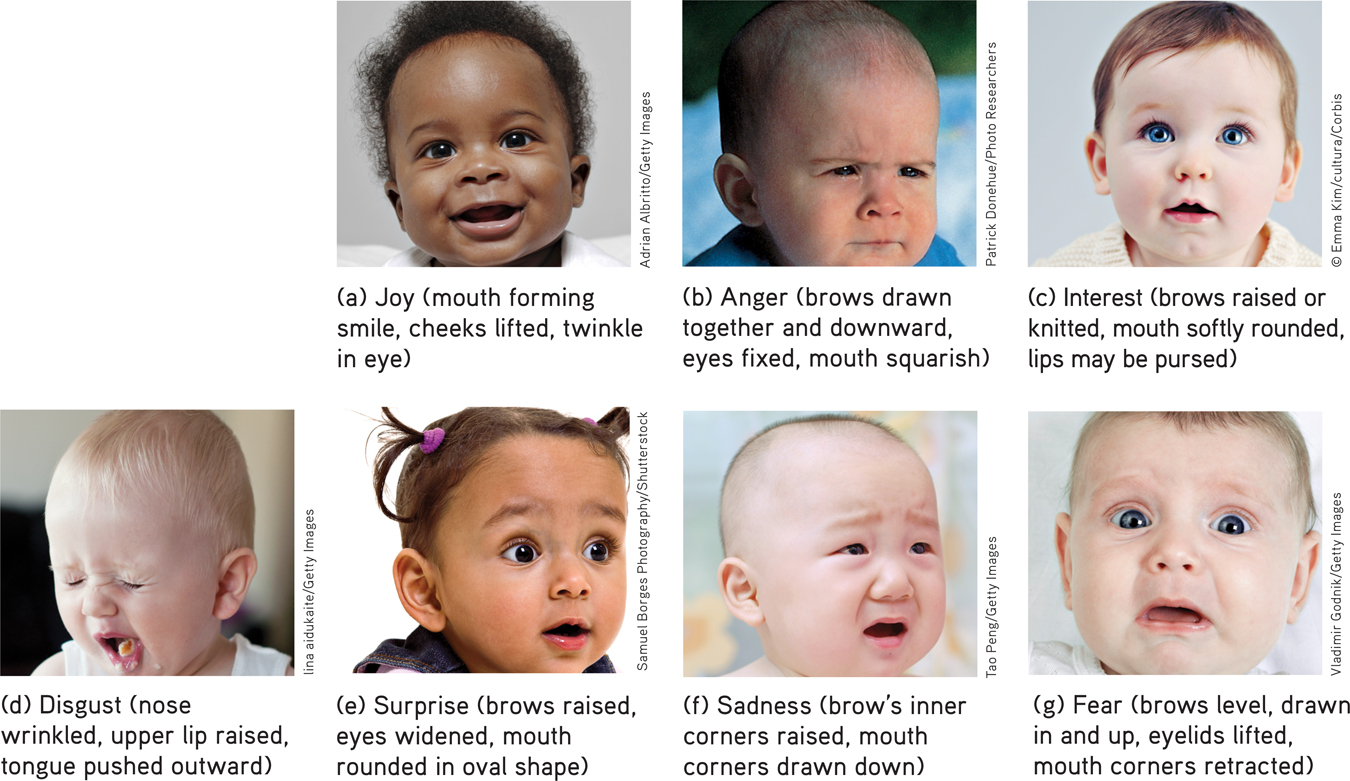

How many distinct emotions are there? Carroll Izard (1977) isolated 10 basic emotions (joy, interest-

Figure 12.13

Figure 12.13Infants’ naturally occurring emotions To identify the emotions present from birth, Carroll Izard analyzed the facial expressions of infants.

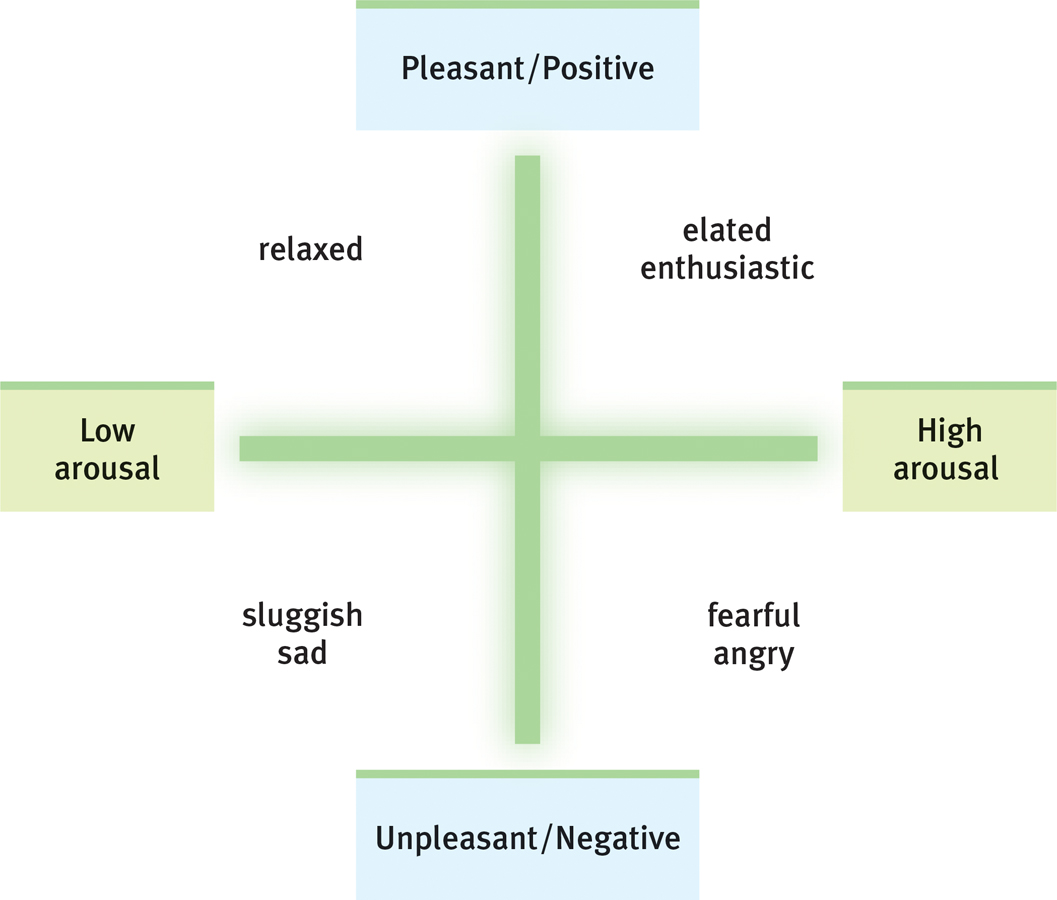

The ingredients of emotion include not only physiology and expressive behavior but also our conscious experience. Across the world, people place emotional experience along the two dimensions illustrated in FIGURE 12.14—positive-

Figure 12.14

Figure 12.14Two dimensions of emotion James Russell, David Watson, Auke Tellegen, and others have described emotions as variations on two dimensions—

Let’s take a closer look at anger and happiness. What functions do they serve? What influences our experience of each?

477

Anger

12-

Anger, the sages have said, is “a short madness” (Horace, 65–

When we face a threat or challenge, fear triggers flight but anger triggers fight—

Anger can harm us: Chronic hostility is linked to heart disease. Anger boosts our heart rate, causes our skin to drip with sweat, and raises our testosterone levels (Herrero et al., 2010; Kubo et al., 2012; Peterson & Harmon-

Individualist cultures encourage people to vent their rage. Such advice is seldom heard in cultures where people’s identity is centered more on the group. People who keenly sense their interdependence see anger as a threat to group harmony (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In Tahiti, for instance, people learn to be considerate and gentle. In Japan, from infancy on, angry expressions are less common than in Western cultures, where in recent politics, anger seems all the rage.

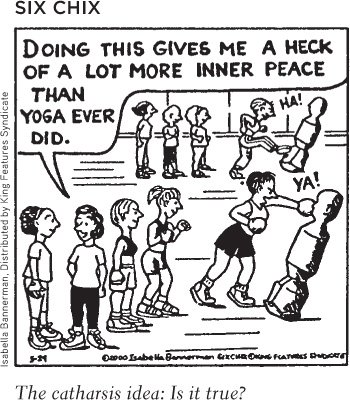

The Western vent-

- they direct their counterattack toward the provoker.

- their retaliation seems justifiable.

- their target is not intimidating.

catharsis emotional release. In psychology, the catharsis hypothesis maintains that “releasing” aggressive energy (through action or fantasy) relieves aggressive urges.

In short, expressing anger can be temporarily calming if it does not leave us feeling guilty or anxious. But despite this temporary afterglow, catharsis usually fails to cleanse our rage. More often, expressing anger breeds more anger. For one thing, it may provoke further retaliation, causing a minor conflict to escalate into a major confrontation. For another, expressing anger can magnify anger. As behavior feedback research demonstrates, acting angry can make us feel angrier (Flack, 2006; Snodgrass et al., 1986). Anger’s backfire potential appeared in a study of 100 frustrated engineers and technicians just laid off by an aerospace company (Ebbesen et al., 1975). Researchers asked some workers questions that released hostility, such as, “What instances can you think of where the company has not been fair with you?” After expressing their anger, the workers later filled out a questionnaire that assessed their attitudes toward the company. Had the opportunity to “drain off” their hostility reduced it? Quite the contrary. These people expressed more hostility than those who had discussed neutral topics.

478

In another study, people who had been provoked were asked to wallop a punching bag while ruminating about the person who had angered them. Later, when given a chance for revenge, they became even more aggressive. “Venting to reduce anger is like using gasoline to put out a fire,” concluded the researcher (Bushman, 2002).

When anger fuels physically or verbally aggressive acts we later regret, it becomes maladaptive. Anger primes prejudice. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Americans who responded with anger more than fear displayed intolerance for immigrants and Muslims (DeSteno et al., 2004; Skitka et al., 2004). Angry outbursts that temporarily calm us are dangerous in another way: They may be reinforcing and therefore habit forming. If stressed managers find they can drain off some of their tension by berating an employee, then the next time they feel irritated and tense they may be more likely to explode again. Think about it: The next time you are angry you are likely to repeat whatever relieved (and reinforced) your anger in the past.

What is the best way to manage your anger? Experts offer three suggestions:

- Wait. You can reduce the level of physiological arousal of anger by waiting. “It is true of the body as of arrows,” noted Carol Tavris (1982), “what goes up must come down. Any emotional arousal will simmer down if you just wait long enough.”

- Find a healthy distraction or support. Calm yourself by exercising, playing an instrument, or talking things through with a friend. Brain scans show that ruminating inwardly about why you are angry serves only to increase amygdala blood flow (Fabiansson et al., 2012).

- Distance yourself. Try to move away from the situation mentally, as if you are watching it unfold from a distance. Self-

distancing reduces rumination, anger, and aggression (Kross & Ayduk, 2011; Mischkowski et al., 2012).

“Anger will never disappear so long as thoughts of resentment are cherished in the mind.”

The Buddha, 500 b.c.e.

Anger is not always wrong. Used wisely, it can communicate strength and competence (Tiedens, 2001). Anger also motivates people to take action and achieve goals (Aarts et al., 2010). Controlled expressions of anger are more adaptive than either hostile outbursts or pent-

What if someone’s behavior really hurts you, and you cannot resolve the conflict? Research commends the age-

Question

c86Mcrdmipg3MbEKxoLb6M+0oKxT0u7dq75/hf/ERFaujHfhmbeIoE8htilF9o0L4nFNwRifvRqrSXod4QVDyKw9WkpvLN7fp4WkYvIqL0I3aP1FFLMiQqebPdDFLma8AqvatCw20Rzfj1FzzDkouUKEJmbT8lwcjdnhFEEvYRVne6UV8nhiTkWik7OF91+6VjtyQ86PYdW3xZC/IWS4ewv8K9aEwYSNGUoxaHczaWrKI6arYlTUYnMXGPdND6ZIxubi0wAvytir5LxsRETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which one of the following is an effective strategy for reducing angry feelings?

|

a. Retaliate verbally or physically. b. Wait or “simmer down.” |

d. Express anger in action or fantasy. e. Review the grievance silently. |

b

479

Happiness

12-

feel-

People aspire to, and wish one another, health and happiness. And for good reason. Our state of happiness or unhappiness colors everything. Happy people perceive the world as safer and feel more confident. They are more decisive and cooperate more easily. They rate job applicants more favorably, savor their positive past experiences without dwelling on the negative, and are more socially connected. They live healthier and more energized and satisfied lives (DeNeve et al., 2013; Mauss et al., 2011). When your mood is gloomy, life as a whole seems depressing and meaningless—

This helps explain why college students’ happiness helps predict their life course. One study showed that the happiest 20-

Moreover—

The reverse is also true: Doing good also promotes good feeling. Feeling good, for example, increases people’s willingness to donate kidneys. And kidney donation leaves donors feeling good (Brethel-

Positive Psychology

William James was writing about the importance of happiness (“the secret motive for all [we] do”) as early as 1902. By the 1960s, the humanistic psychologists were interested in advancing human fulfillment. In the twenty-

- positive emotions by assessing exercises and interventions aimed at increasing happiness (Schueller, 2010; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009).

- positive health by studying how positive emotions enhance and sustain physical well-

being (Seligman, 2008; Seligman et al., 2011). - positive neuroscience by examining the biological foundations of positive emotions, resilience, and social behavior (www.posneuroscience.org).

- positive education by evaluating educational efforts to increase students’ engagement, resilience, character strengths, optimism, and sense of meaning (Seligman et al., 2009).

positive psychology the scientific study of human flourishing, with the goals of discovering and promoting strengths and virtues that help individuals and communities to thrive.

subjective well-

480

Taken together, satisfaction with the past, happiness with the present, and optimism about the future define the positive psychology movement’s first pillar: positive well-

Positive psychology is about building not just a pleasant life, says Seligman, but also a good life that engages one’s skills, and a meaningful life that points beyond oneself. Thus, the second pillar, positive character, focuses on exploring and enhancing creativity, courage, compassion, integrity, self-

The third pillar, positive groups, communities, and cultures, seeks to foster a positive social ecology. This includes healthy families, communal neighborhoods, effective schools, socially responsible media, and civil dialogue.

“Positive psychology,” Seligman and colleagues have said (2005), “is an umbrella term for the study of positive emotions, positive character traits, and enabling institutions.” Its focus differs from psychology’s traditional interests during its first century, when attention was directed toward understanding and alleviating negative states—

In ages past, times of relative peace and prosperity have enabled cultures to turn their attention from repairing weakness and damage to promoting what Seligman (2002) has called “the highest qualities of life.” Prosperous fifth-

Will psychology have a more positive mission in this century? Without slighting the need to repair damage and cure disease, positive psychology’s proponents hope so. With American Psychologist and British Psychologist special issues devoted to positive psychology; with many new books; with networked scientists working in worldwide research groups; and with prizes, research awards, summer institutes, and a graduate program promoting positive psychology scholarship, these psychologists have reason to be positive. Cultivating a more positive psychology mission may help Seligman achieve his most ambitious goal: By the year 2051, 51 percent of the world will be “flourishing.” “It’s in our hands not only to witness this,” he says, “but to take part in making this happen” (Seligman, 2011).

The Short Life of Emotional Ups and Downs

12-

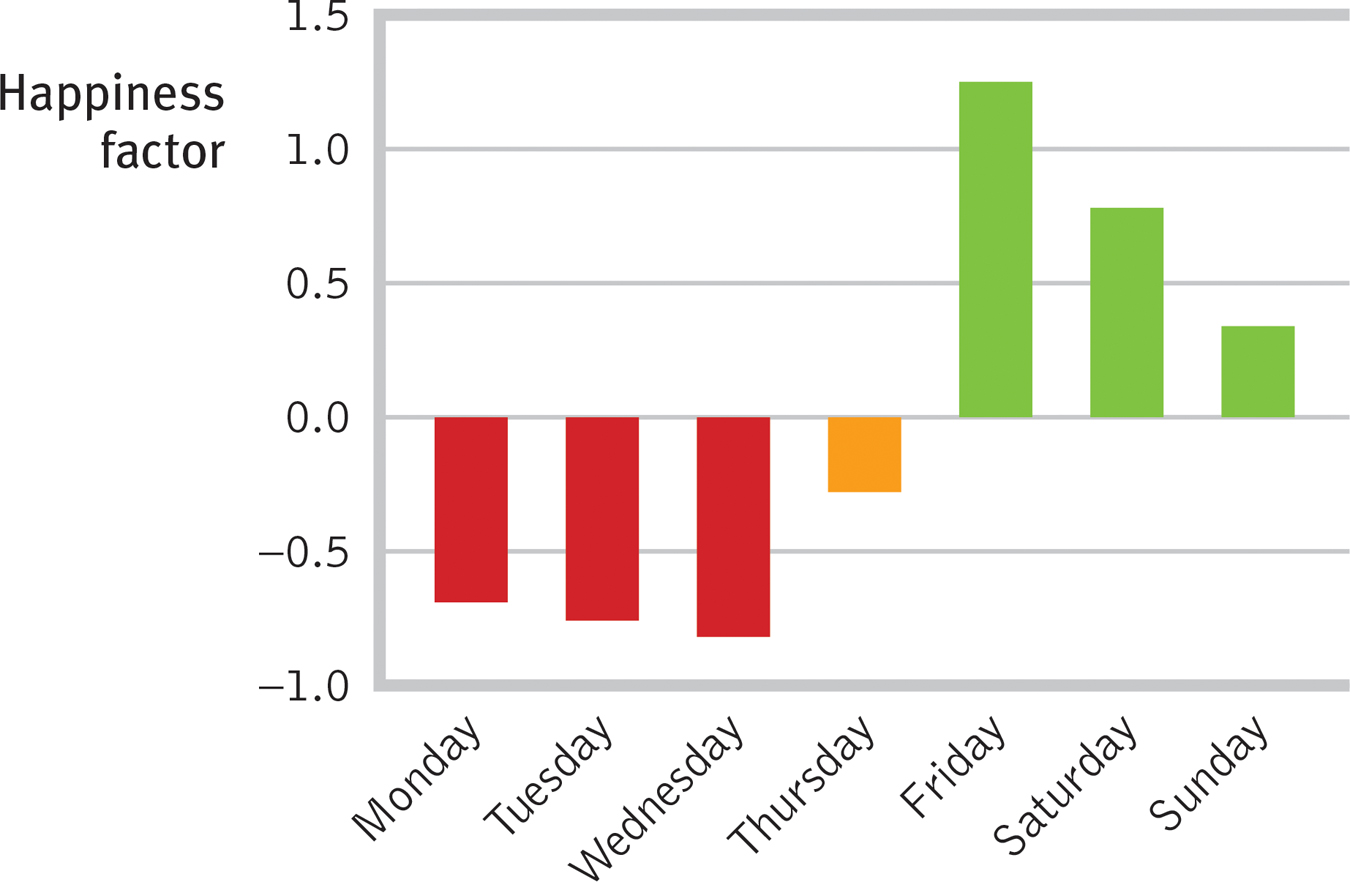

Are some days of the week happier than others? In what is likely psychology’s biggest-

Figure 12.15

Figure 12.15Using Web science to track happy days Adam Kramer (personal correspondence, 2010) tracked positive and negative emotion words in many “billions” (the exact number is proprietary information) of status updates of U.S. users of Facebook between September 7, 2007, and November 17, 2010.

“No happiness lasts for long.”

Seneca, Agamemnon, c.e. 60

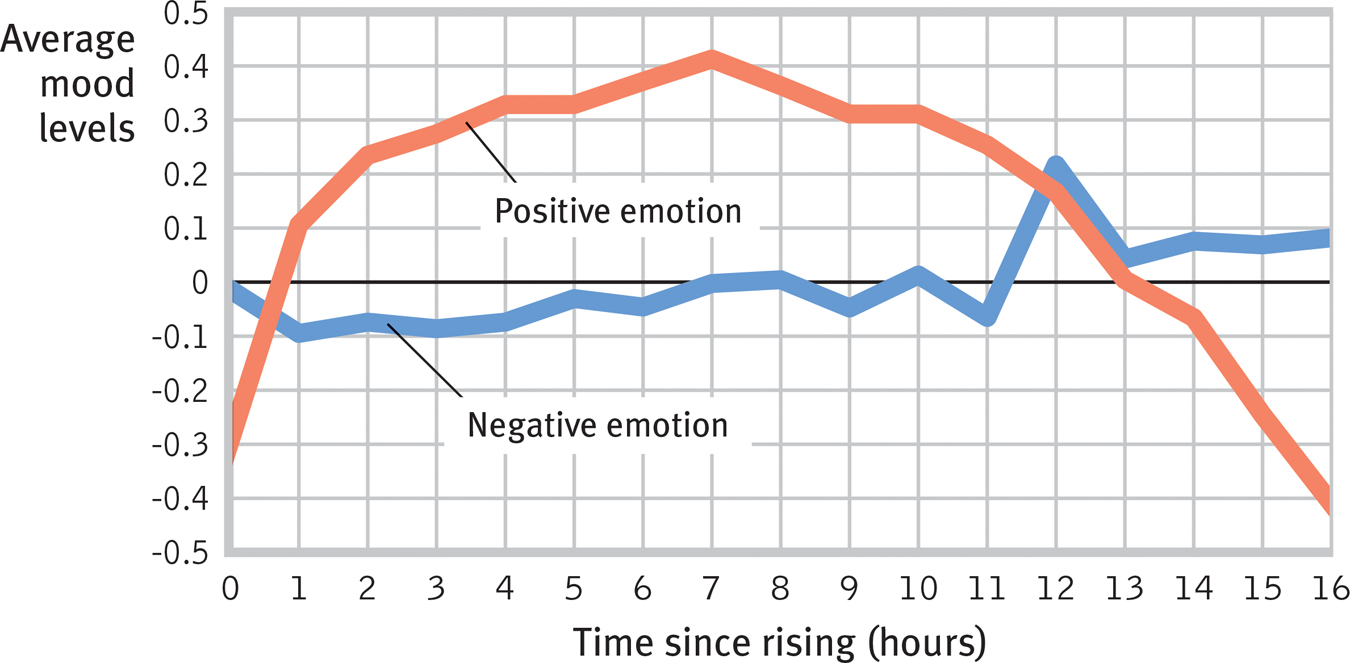

Over the long run, our emotional ups and downs tend to balance out. This is true even over the course of the day (FIGURE 12.16). Positive emotion rises over the early to middle part of most days and then drops off (Kahneman et al., 2004; Watson, 2000). A stressful event—

Figure 12.16

Figure 12.16Moods across the day When psychologist David Watson (2000) sampled nearly 4500 mood reports from 150 people, he found this pattern of variation from the average levels of positive and negative emotions.

481

Even when negative events drag us down for longer periods, our bad mood usually ends. A romantic breakup feels devastating, but eventually the wound heals. In one study, faculty members up for tenure expected their lives would be deflated by a negative decision. Actually, 5 to 10 years later, their happiness level was about the same as for those who received tenure (Gilbert et al., 1998).

Grief over the loss of a loved one or anxiety after a severe trauma (such as child abuse, rape, or the terrors of war) can linger. But usually, even tragedy is not permanently depressing. People who become blind or paralyzed may not completely recover their previous well-

“Weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes with the morning.”

Psalm 30:5

The surprising reality: We overestimate the duration of our emotions and underestimate our resiliency and capacity to adapt. (As one who inherited hearing loss with a trajectory toward that of my mother, who spent the last 13 years of her life completely deaf, I [DM] take heart from these findings.)

482

Wealth and Well-

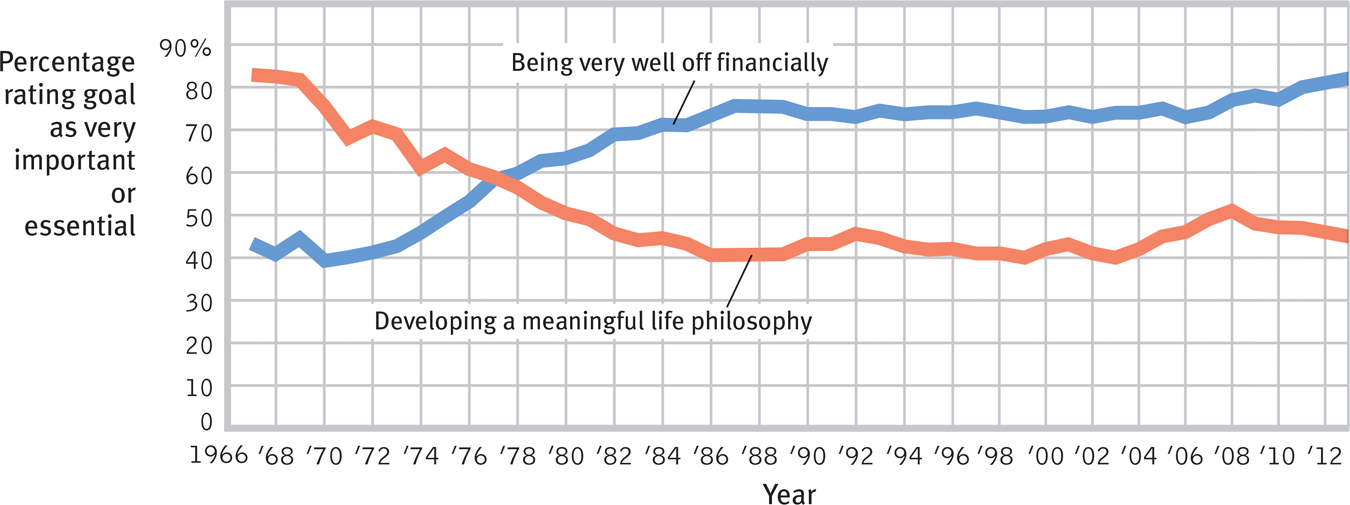

“Do you think you would be happier if you made more money?” Yes, replied 73 percent of Americans in a 2006 Gallup poll. How important is “Being very well off financially?” Very important, say 82 percent of entering U.S. collegians (FIGURE 12.17).

Figure 12.17

Figure 12.17The changing materialism of entering collegians Surveys of more than 200,000 entering U.S. collegians per year have revealed an increasing desire for wealth after 1970. (Data from The American Freshman surveys, UCLA, 1966 to 2013.)

And to a point, wealth does correlate with well-

- In most countries, and especially in poor countries, individuals with lots of money are typically happier than those who struggle to afford life’s basic needs (Diener & Biswas-

Diener, 2009; Howell & Howell, 2008; Lucas & Schimmack, 2009). And, as we will see, they often enjoy better health than those stressed by poverty and lack of control over their lives. - People in rich countries also experience greater well-

being than those in poor countries (Diener et al., 2009; Inglehart, 2008; Tay & Diener, 2011). The same is true for those in higher- income American states (Oswald & Wu, 2010).

So, it seems that having enough money to buy your way out of hunger and to have a sense of control over your life does buy some happiness (Fischer & Boer, 2011). As Australian data confirm, the power of more money to increase happiness is significant at low incomes and diminishes as income rises (Cummins, 2006). A $1000 annual wage increase does a lot more for the average person in Malawi than for the average person in Switzerland. This implies that raising low incomes will do more to increase happiness than raising high incomes.

Once one has enough money for comfort and security, piling up more and more matters less and less. Experiencing luxury diminishes our savoring of life’s simpler pleasures (Quoidbach et al., 2010). If you’ve skied the Alps, your neighborhood sledding hill pales.

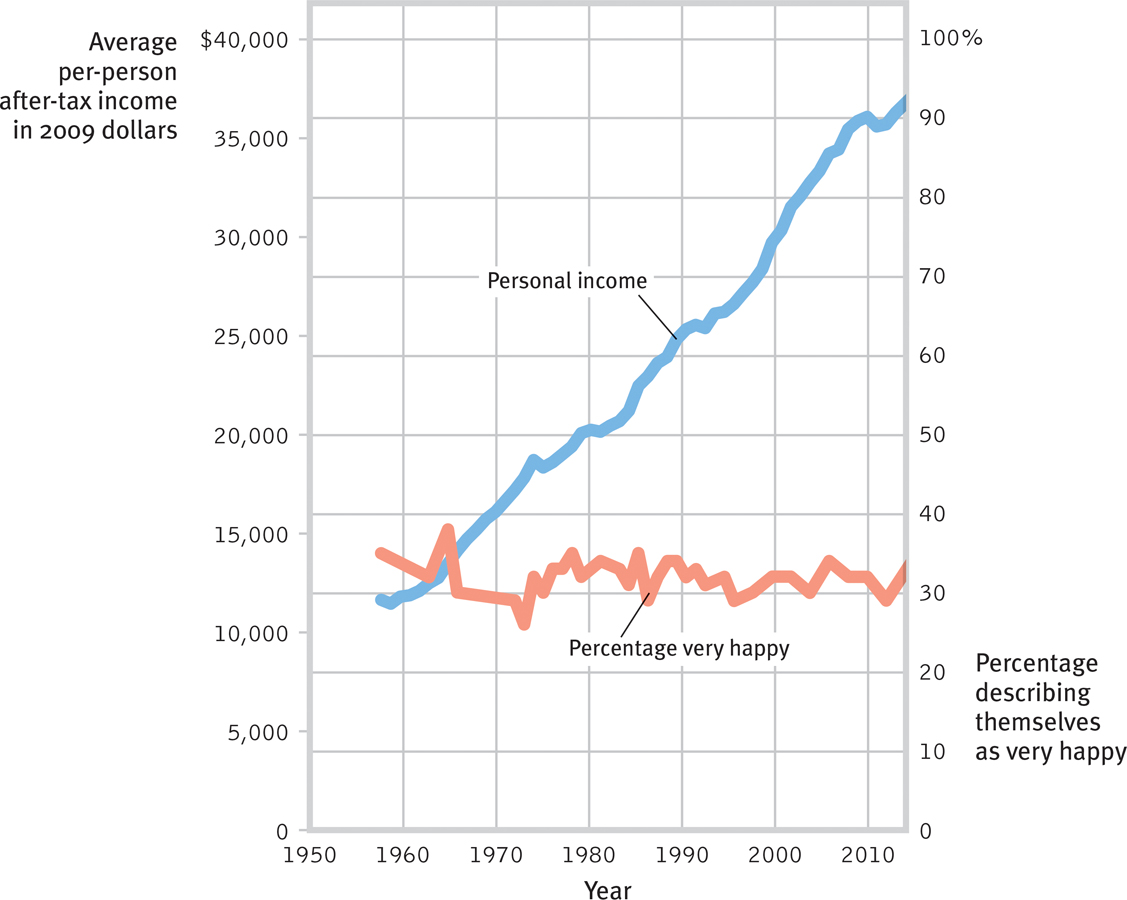

And consider this: During the last half-

Figure 12.18

Figure 12.18Does money buy happiness? It surely helps us to avoid certain types of pain. Yet, though buying power has almost tripled since the 1950s, the average American’s reported happiness has remained almost unchanged. (Happiness data from National Opinion Research Center surveys; income data from Historical Statistics of the United States and Economic Indicators.)

“Australians are three times richer than their parents and grandparents were in the 1950s, but they are not happier.”

A Manifesto for Well-

Ironically, in every culture, those who strive hardest for wealth have tended to live with lower well-

483

adaptation-

Two Psychological Phenomena: Adaptation and Comparison

Two psychological principles explain why, for those who are not poor, more money buys little more than a temporary surge of happiness and why our emotions seem attached to elastic bands that pull us back from highs or lows. In its own way, each principle suggests that happiness is relative.

“Continued pleasures wear off.… Pleasure is always contingent upon change and disappears with continuous satisfaction.”

Dutch psychologist Nico Frijda (1988)

Happiness Is Relative to Our Own Experience The adaptation-

“I have a ‘fortune cookie maxim’ that I’m very proud of: Nothing in life is quite as important as you think it is while you are thinking about it. So, nothing will ever make you as happy as you think it will.”

Nobel laureate psychologist Daniel Kahneman, Gallup interview, “What Were They Thinking?” 2005

relative deprivation the perception that one is worse off relative to those with whom one compares oneself.

484

So, could we ever create a permanent social paradise? Probably not (Campbell, 1975; Di Tella et al., 2010). People who have experienced a recent windfall—

Happiness Is Relative to Others’ Success We are always comparing ourselves with others. And whether we feel good or bad depends on who those others are (Lyubomirsky, 2001). We are slow-

The effect of comparison with others helps explain why students of a given level of academic ability tended to have a higher academic self-

Satisfaction stems less from our income than from our income rank (Boyce et al., 2010). Better to make $50,000 when others make $25,000 than to make $100,000 when friends, neighbors, and co-

Such comparisons help us understand why the middle-

“Comparison is the thief of joy.”

Attributed to Theodore Roosevelt

Over the last half century, inequality in Western countries has increased. The rising economic tide shown in Figure 12.18 has lifted the yachts faster than the rowboats. Does it matter? Places with great inequality have higher crime rates, obesity, anxiety, and drug use, and lower life expectancy (Kawachi et al., 1999; Ratcliff, 2013; Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009). Times and places with greater income inequality also tend to be less happy—

Just as comparing ourselves with those who are better off creates envy, so counting our blessings as we compare ourselves with those worse off boosts our contentment. In one study, University of Wisconsin-

What Predicts Our Happiness Levels?

12-

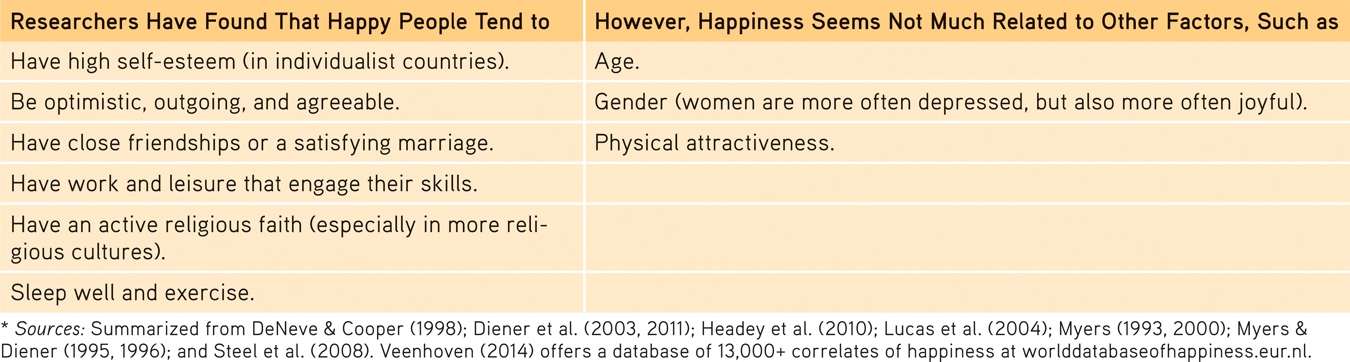

Happy people share many characteristics (TABLE 12.2). But why are some people normally so joyful and others so somber? Here, as in so many other areas, the answer is found in the interplay between nature and nurture.

Table 12.2

Table 12.2Happiness Is …

485

Genes matter. In one study of hundreds of identical and fraternal twins, about 50 percent of the difference among people’s happiness ratings was heritable (Gigantesco et al., 2011; Lykken & Tellegen, 1996). Other twin studies report similar or slightly less heritability (Bartels & Boomsma, 2009; Lucas, 2008; Nes et al., 2010). Identical twins raised apart are often similarly happy. Moreover, researchers are now drilling down to identify how specific genes influence our happiness (De Neve et al., 2012; Fredrickson et al., 2013).

But our personal history and our culture matter, too. On the personal level, as we have seen, our emotions tend to balance around a level defined by our experience. On the cultural level, groups vary in the traits they value. Self-

Depending on our genes, our outlook, and our recent experiences, our happiness seems to fluctuate around our “happiness set point,” which disposes some people to be ever upbeat and others more negative. Even so, after following thousands of lives over two decades, researchers have determined that our satisfaction with life is not fixed (Lucas & Donnellan, 2007). Happiness rises and falls, and can be influenced by factors that are under our control. A striking example: In a long-

If we can enhance our happiness on an individual level, could we use happiness research to refocus our national priorities more on the pursuit of happiness? Many psychologists believe we could. Ed Diener (2006, 2009, 2013), supported by 52 colleagues, has proposed ways in which nations might measure national well-

Happiness research offers new ways to assess the impacts of various public policies, argue Diener and his colleagues. Happy societies are not only prosperous, but also places where people trust one another, feel free, and enjoy close relationships (Helliwell et al., 2013; Oishi & Schimmack, 2010). Thus, in debates about the minimum wage, economic inequality, tax rates, divorce laws, health care, and city planning, people’s psychological well-

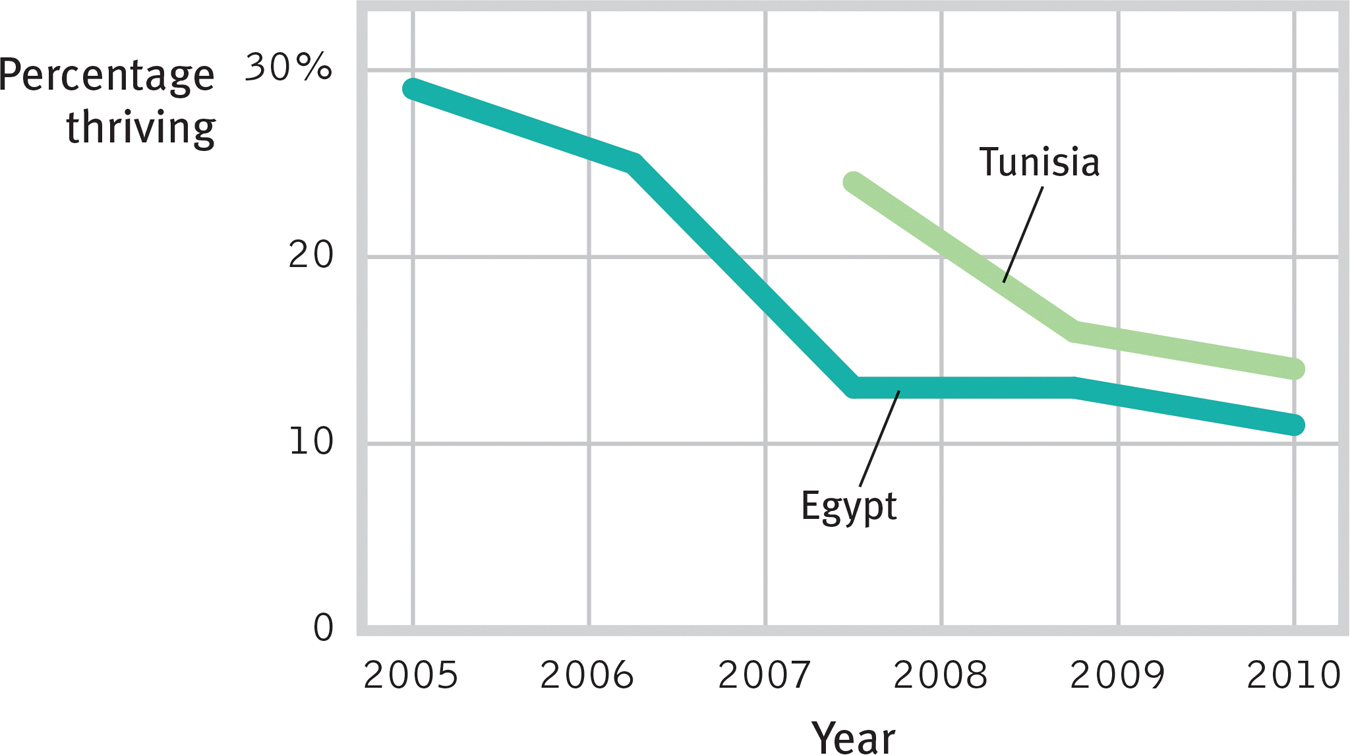

Figure 12.19

Figure 12.19Declining well-

486

Evidence-

Your happiness, like your cholesterol level, is genetically influenced. Yet as cholesterol is also influenced by diet and exercise, so happiness is partly under your control (Layous & Lyubomirsky, 2014; Nes, 2010). Here are 11 research-

- Realize that enduring happiness may not come from financial success. We adapt to change by adjusting our expectations. Neither wealth, nor any other circumstance we long for, will guarantee happiness.

- Take control of your time. Happy people feel in control of their lives. To master your use of time, set goals and break them into daily aims. This may be frustrating at first because we all tend to overestimate how much we will accomplish in any given day. The good news is that we generally underestimate how much we can accomplish in a year, given just a little progress every day.

- Act happy. Research shows that people who are manipulated into a smiling expression feel better. So put on a happy face. Talk as if you feel positive self-

esteem, are optimistic, and are outgoing. We can often act our way into a happier state of mind. - Seek work and leisure that engage your skills. Happy people often are in a zone called flow—absorbed in tasks that challenge but don’t overwhelm them. The most expensive forms of leisure (sitting on a yacht) often provide less flow experience than simpler forms, such as gardening, socializing, or craft work.

- Buy shared experiences rather than things. Compared with money spent on stuff, money buys more happiness when spent on experiences that you look forward to, enjoy, remember, and talk about (Carter & Gilovich, 2010; Kumar & Gilovich, 2013). This is especially so for socially shared experiences (Caprariello & Reis, 2012). The shared experience of a college education may cost a lot, but, as pundit Art Buchwald said, “The best things in life aren’t things.”

- Join the “movement” movement. Aerobic exercise can relieve mild depression and anxiety as it promotes health and energy. Sound minds reside in sound bodies. Off your duffs, couch potatoes!

- Give your body the sleep it wants. Happy people live active lives yet reserve time for renewing sleep and solitude. Many people suffer from sleep debt, with resulting fatigue, diminished alertness, and gloomy moods.

- Give priority to close relationships. Intimate friendships can help you weather difficult times. Confiding is good for soul and body. Compared with unhappy people, happy people engage in less superficial small talk and more meaningful conversations (Mehl et al., 2010). So resolve to nurture your closest relationships by not taking your loved ones for granted. This means displaying to them the sort of kindness you display to others, affirming them, playing together, and sharing together.

- Focus beyond self. Reach out to those in need. Perform acts of kindness. Happiness increases helpfulness (those who feel good do good). But doing good also makes us feel good.

- Count your blessings and record your gratitude. Keeping a gratitude journal heightens well-

being (Emmons, 2007; Seligman et al., 2005). When something good happens, such as an achievement, take time to appreciate and savor the experience (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012). Record positive events and why they occurred. Express your gratitude to others. - Nurture your spiritual self. For many people, faith provides a support community, a reason to focus beyond self, and a sense of purpose and hope. That helps explain why people active in faith communities report greater-

than- average happiness and often cope well with crises.

Question

bvtEkKzXcwm7ONcbaMh0L6oO09mFBolGC8JA6c6DAizkb3u0WYDWIwq+fQXmwixuRqQ47vFl7st8GMtmf2Fk3V4VMQuYiXJeKDHhJp/QSOgozKR5gbXusLAjZqAhf80CXmB8xnM4OFr1xaJ+V9UD9Cvy45EfVgHVt7Hmol1ckj0Lcb080oxcIA/r4fiGUJBUEL4PihLbSPijc2iIteloDOuhARyqSGXKkz37BP0JZZdWqMEUnTC/j6tdN8qoa+/Lfk54uv8mrouDhrk4ARNKrSXSIwJYEApHUu6+1JC7c0E=487

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which of the following factors do NOT predict self-

reported happiness? Which factors are better predictors?

|

a. Age b. Personality traits c. Close relationships |

d. Gender e. Sleep and exercise f. Religious faith |

Age and gender (a. and d.) do NOT effectively predict happiness levels. Better predictors are personality traits, close relationships, sleep and exercise, and religious faith (b., c., e., and f.).