13.4 Prosocial Relations

Social psychologists focus not only on the dark side of social relationships, but also on the bright side, by studying prosocial behavior—

Attraction

Pause a moment and think about your relationships with two people—

The Psychology of Attraction

13-

mere exposure effect the phenomenon that repeated exposure to novel stimuli increases liking of them.

We endlessly wonder how we can win others’ affection and what makes our own affections flourish or fade. Does familiarity breed contempt, or does it amplify affection? Do birds of a feather flock together, or do opposites attract? Is beauty only skin deep, or does physical attractiveness matter greatly? To explore these questions, let’s consider three ingredients of our liking for one another: proximity, attractiveness, and similarity.

Proximity Before friendships become close, they must begin. Proximity—geographic nearness—

Proximity breeds liking partly because of the mere exposure effect. Repeated exposure to novel stimuli increases our liking for them. This applies to nonsense syllables, musical selections, geometric figures, Chinese characters, human faces, and the letters of our own name (Moreland & Zajonc, 1982; Nuttin, 1987; Zajonc, 2001). We are even somewhat more likely to marry someone whose first or last name resembles our own (Jones et al., 2004).

So, within certain limits, familiarity feeds fondness (Bornstein, 1989, 1999). Researchers demonstrated this by having four equally attractive women silently attend a 200-

552

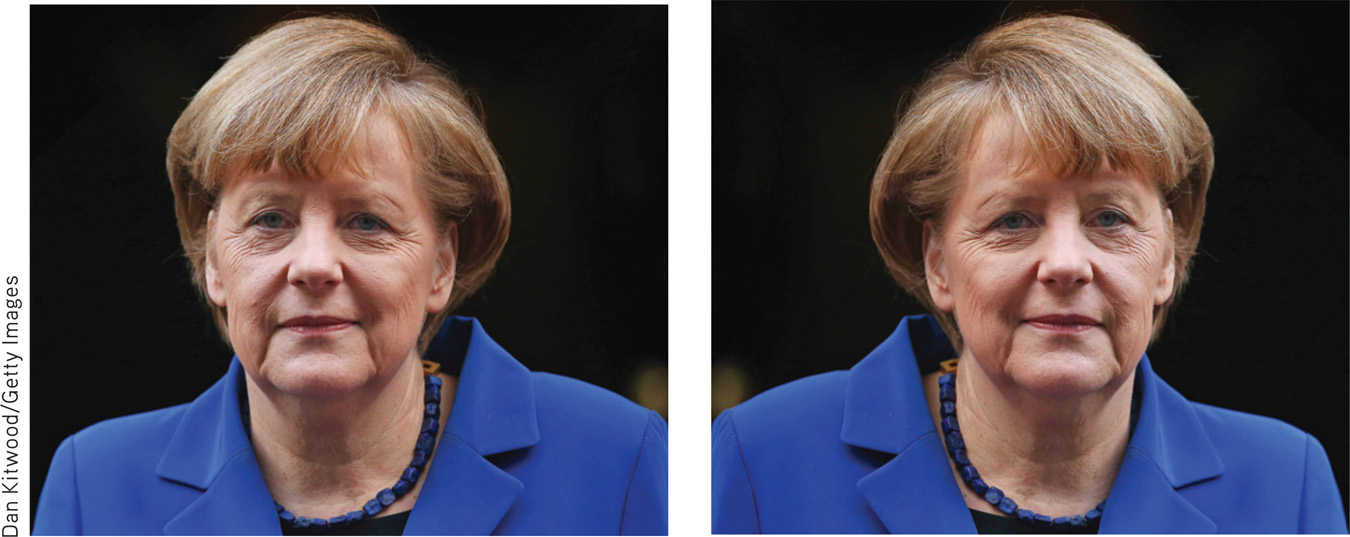

No face is more familiar than your own. And that helps explain an interesting finding by Lisa DeBruine (2004): We like other people when their faces incorporate some morphed features of our own. When DeBruine (2002) had McMaster University students (both men and women) play a game with a supposed other player, they were more trusting and cooperative when the other person’s image had some of their own facial features morphed into it. In me I trust. (See also FIGURE 13.14.)

Figure 13.14

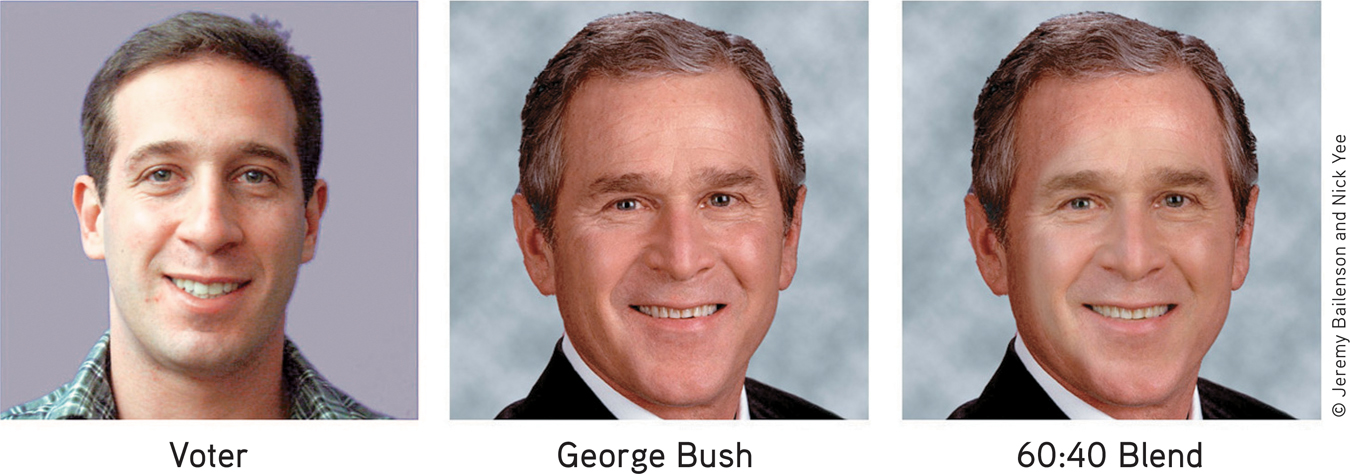

Figure 13.14I like the candidate who looks a bit like dear old me Jeremy Bailenson and his colleagues (2005) incorporated morphed features of voters’ faces into the faces of 2004 U.S. presidential candidates George Bush and John Kerry. Without conscious awareness of their own incorporated features, the participants became more likely to favor the candidate whose face incorporated some of their own features.

For our ancestors, the mere exposure effect had survival value. What was familiar was generally safe and approachable. What was unfamiliar was more often dangerous and threatening. Evolution may therefore have hard-

Modern Matchmaking Those who have not found a romantic partner in their immediate proximity may cast a wider net by joining an online dating service. Published research on Internet matchmaking effectiveness is sparse. But this much seems well established: Some people, including occasional predators, dishonestly represent their age, attractiveness, occupation, or other details, and thus are not who they seem to be. Nevertheless, Katelyn McKenna and John Bargh and their colleagues have offered a surprising finding: Compared with relationships formed in person, Internet-

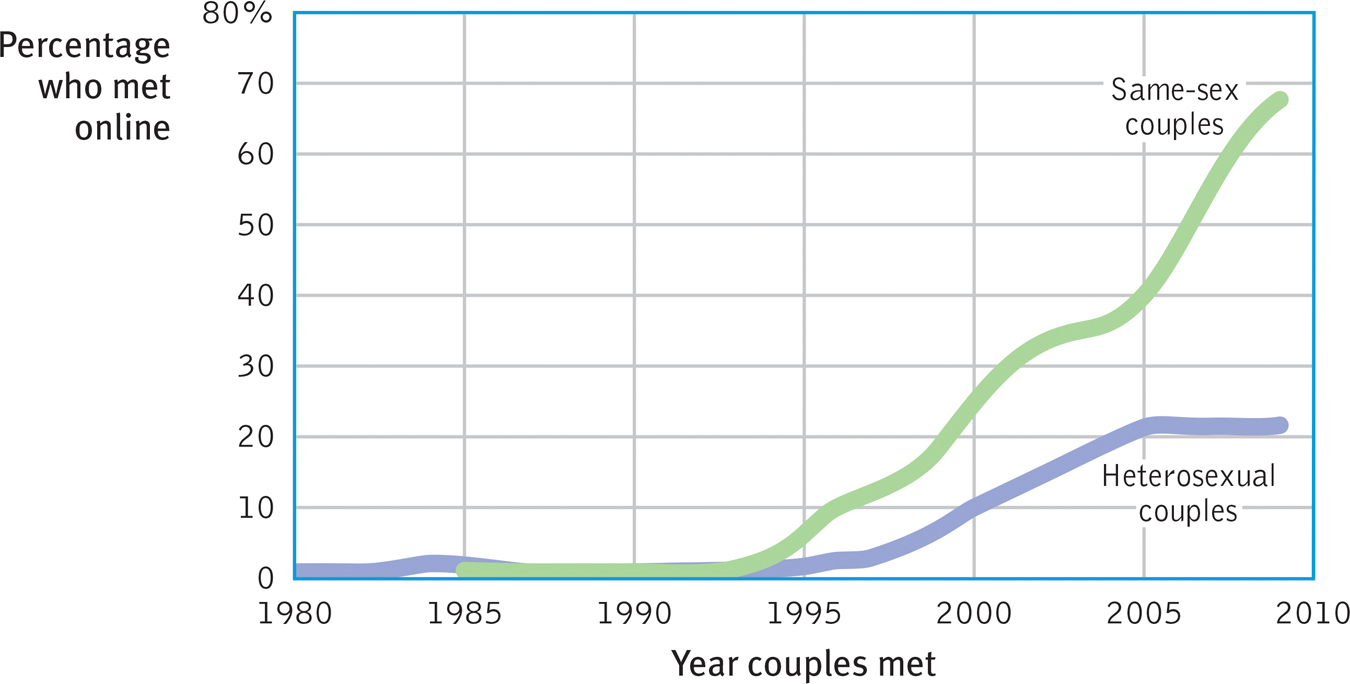

Figure 13.15

Figure 13.15Percent of heterosexual and same-

Speed dating pushes the search for romance into high gear. In a process pioneered by a matchmaking Jewish rabbi, people meet a succession of prospective partners, either in person or via webcam (Bower, 2009). After a 3-

553

For researchers, speed dating offers a unique opportunity for studying influences on our first impressions of potential romantic partners. Among recent findings are these:

- Men are more transparent. Observers (male or female) watching videos of speed-

dating encounters can read a man’s level of romantic interest more accurately than a woman’s (Place et al., 2009). - Given more options, people’s choices become more superficial. Meeting lots of potential partners leads people to focus on more easily assessed characteristics, such as height and weight (Lenton & Francesconi, 2010). This was true even when researchers controlled for time spent with each partner.

- Men wish for future contact with more of their speed dates; women tend to be more choosy. But this difference disappears if the conventional roles are reversed, so that men stay seated while women circulate (Finkel & Eastwick, 2009).

Physical Attractiveness Once proximity affords us contact, what most affects our first impressions? The person’s sincerity? Intelligence? Personality? Hundreds of experiments reveal that it is something far more superficial: physical appearance. This finding is unnerving for those of us taught that “beauty is only skin deep” and “appearances can be deceiving.”

In one early study, researchers randomly matched new University of Minnesota students for a Welcome Week dance (Walster et al., 1966). Before the dance, the researchers gave each student a battery of personality and aptitude tests, and they rated each student’s physical attractiveness. During the blind date, the couples danced and talked for more than two hours and then took a brief intermission to rate their dates. What determined whether they liked each other? Only one thing seemed to matter: appearance. Both the men and the women liked good-

Physical attractiveness also predicts how often people date and how popular they feel. It affects initial impressions of people’s personalities. We don’t assume that attractive people are more compassionate, but research participants perceive them as healthier, happier, more sensitive, more successful, and more socially skilled (Eagly et al., 1991; Feingold, 1992; Hatfield & Sprecher, 1986). Attractive, well-

554

“Personal beauty is a greater recommendation than any letter of introduction.”

Aristotle, Apothegems, 330 b.c.e.

Even babies have preferred attractive over unattractive faces (Langlois et al., 1987). So do some blind people, as University of Birmingham professor John Hull (1990, p. 23) discovered after going blind. A colleague’s remarks on a woman’s beauty would strangely affect his feelings. He found this “deplorable.… What can it matter to me what sighted men think of women … yet I do care what sighted men think, and I do not seem able to throw off this prejudice.”

For those who find the importance of looks unfair and unenlightened, two findings may be reassuring. First, people’s attractiveness is surprisingly unrelated to their self-

Beauty is also in the eye of the culture. Hoping to look attractive, people across the globe have pierced and tattooed their bodies, lengthened their necks, bound their feet, and dyed their hair. They have gorged themselves to achieve a full figure or liposuctioned fat to achieve a slim one, applied chemicals hoping to rid themselves of unwanted hair or to regrow wanted hair, strapped on leather garments to make their breasts seem smaller or surgically filled their breasts with silicone and worn Wonder-

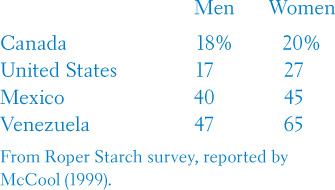

Percentage of Men and Women Who “Constantly Think About Their Looks”

From Roper Starch survey, reported by McCool (1999).

Some aspects of attractiveness, however, do cross place and time (Cunningham et al., 2005; Langlois et al., 2000). By providing reproductive clues, bodies influence sexual attraction. As evolutionary psychologists explain (see Chapter 4), men in many cultures, from Australia to Zambia, judge women as more attractive if they have a youthful, fertile appearance, suggested by a low waist-

Women have 91 percent of cosmetic procedures (ASPS, 2010). Women also recall others’ appearances better than do men (Mast & Hall, 2006).

Estimated length of human nose removed by U.S. plastic surgeons each year: 5469 feet (Harper’s, 2009).

555

People everywhere also seem to prefer physical features—

Figure 13.16

Figure 13.16Average is attractive Which of these faces offered by University of St. Andrews psychologist David Perrett (2002, 2010) is most attractive? Most people say it’s the face on the right—

Our feelings also influence our attractiveness judgments. Imagine two people. The first is honest, humorous, and polite. The second is rude, unfair, and abusive. Which one is more attractive? Most people perceive the person with the appealing traits as more physically attractive (Lewandowski et al., 2007). Those we like we find attractive. In a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, Prince Charming asks Cinderella, “Do I love you because you’re beautiful, or are you beautiful because I love you?” Chances are it’s both. As we see our loved ones again and again, their physical imperfections grow less noticeable and their attractiveness grows more apparent (Beaman & Klentz, 1983; Gross & Crofton, 1977). Shakespeare said it in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: “Love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind.” Come to love someone and watch beauty grow.

Similarity So proximity has brought you into contact with someone, and your appearance has made an acceptable first impression. What influences whether you will become friends? As you get to know each other, will the chemistry be better if you are opposites or if you are alike?

It makes a good story—

556

Moreover, the more alike people are, the more their liking endures (Byrne, 1971). Journalist Walter Lippmann was right to suppose that love lasts “when the lovers love many things together, and not merely each other.” Similarity breeds content. One app therefore matches people with potential dates based on their proximity, and on the similarity of their Facebook profiles.

Proximity, attractiveness, and similarity are not the only determinants of attraction. We also like those who like us. This is especially true when our self-

Indeed, all the findings we have considered so far can be explained by a simple reward theory of attraction: We will like those whose behavior is rewarding to us, including those who are both able and willing to help us achieve our goals (Montoya & Horton, 2014). When people live or work in close proximity to us, it requires less time and effort to develop the friendship and enjoy its benefits. When people are attractive, they are aesthetically pleasing, and associating with them can be socially rewarding. When people share our views, they reward us by validating our beliefs.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- People tend to marry someone who lives or works nearby. This is an example of the ______________ ______________ ______________ in action.

mere exposure effect

- How does being physically attractive influence others’ perceptions?

Being physically attractive tends to elicit positive first impressions. People tend to assume that attractive people are healthier, happier, and more socially skilled than others are.

Romantic Love

13-

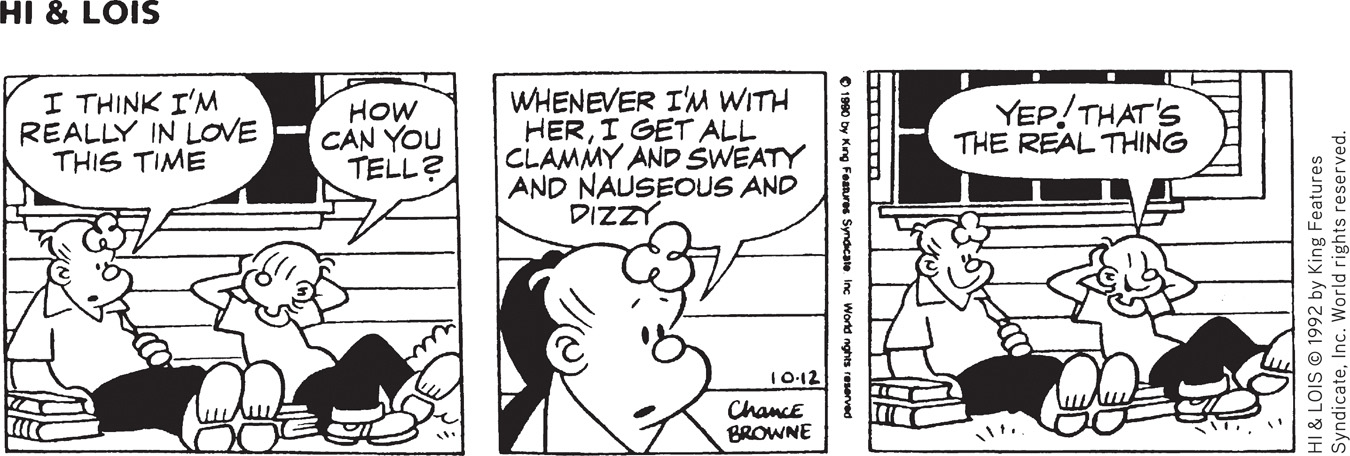

Sometimes people move quickly from initial impressions, to friendship, to the more intense, complex, and mysterious state of romantic love. If love endures, temporary passionate love will mellow into a lingering companionate love (Hatfield, 1988).

Passionate Love A key ingredient of passionate love is arousal. The two-

- emotions have two ingredients—

physical arousal plus cognitive appraisal. - arousal from any source can enhance one emotion or another, depending on how we interpret and label the arousal.

passionate love an aroused state of intense positive absorption in another, usually present at the beginning of a love relationship.

Arousal can come from within, as we experience the excitement of a new relationship. But in tests of the two-

A sample experiment: Researchers studied people crossing two bridges above British Columbia’s rocky Capilano River (Dutton & Aron, 1974, 1989). One, a swaying footbridge, was 230 feet above the rocks; the other was low and solid. The researchers had an attractive young woman intercept men coming off each bridge, and ask their help in filling out a short questionnaire. She then offered her phone number in case they wanted to hear more about her project. Far more of those who had just crossed the high bridge—

companionate love the deep affectionate attachment we feel for those with whom our lives are intertwined.

557

Companionate Love Although the desire and attachment of romantic love often endure, the intense absorption in the other, the thrill of the romance, the giddy “floating on a cloud” feelings typically fade. Does this mean the French are correct in saying that “love makes the time pass and time makes love pass”? Or can friendship and commitment keep a relationship going after the passion cools?

As love matures, it typically becomes a steadier companionate love—a deep, affectionate attachment (Hatfield, 1988). The flood of passion-

There may be adaptive wisdom to the shift from passion to attachment (Reis & Aron, 2008). Passionate love often produces children, whose survival is aided by the parents’ waning obsession with each other. Failure to appreciate passionate love’s limited half-

“When two people are under the influence of the most violent, most insane, most delusive, and most transient of passions, they are required to swear that they will remain in that excited, abnormal, and exhausting condition continuously until death do them part.”

George Bernard Shaw, “Getting Married,” 1908

equity a condition in which people receive from a relationship in proportion to what they give to it.

self-

One key to a gratifying and enduring relationship is equity. When equity exists—

Equity’s importance extends beyond marriage. Mutually sharing one’s self and possessions, making decisions together, giving and getting emotional support, promoting and caring about each other’s welfare—

Another vital ingredient of loving relationships is self-

One experiment marched student pairs through 45 minutes of increasingly self-

558

Intimacy can also grow when we pause to ponder and write our feelings. Researchers invited one person from each of 86 dating couples to spend 20 minutes a day over three days either writing their deepest thoughts and feelings about the relationship or writing merely about their daily activities (Slatcher & Pennebaker, 2006). Those who wrote about their feelings expressed more emotion in their instant messages with their partners in the days following, and 77 percent were still dating three months later (compared with 52 percent of those who had written about their activities).

In addition to equity and self-

In the mathematics of love, self-

Question

jJhl5uxhI2SeKcSsg+YfwdoHH962kY0ihPfdBww/6r9/oLO634eHYgluZsWHzW5h/3uyI4cECbwXAdjIH1Or1jGiMa3mdHiMZEjt2wX2ae39lT8C/zffPr7WPEGfES+/Ru3qesrCaa2DFDpbV/Ibf50dflaporZxfPxhZM3sKOA5M4mggndl9qiMFRYFqxR1m00VEuUhYjQ+2ICYH4TaZUzIjQ6IxFeWMg1wivYjnomnREKrPywJ3kT7MTcTK0dPAi/O/h2jEkIxIN3FM/AtWhJPhPb1GDPlV2Lu/ZH4cGb2FCagaqa2SRm9T2hSda9+c8TuGYmLD54Thv0r2IblV5PHm10U1LqBkbcoNe6/4RY=RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How does the two-

factor theory of emotion help explain passionate love?

Emotions consist of (1) physical arousal and (2) our interpretation of that arousal. Researchers have found that any source of arousal (running, fear, laughter) may be interpreted as passion in the presence of a desirable person.

- Two vital components for maintaining companionate love are ______________ and ______________-______________.

equity; self-

Altruism

altruism unselfish regard for the welfare of others.

13-

Altruism is an unselfish concern for the welfare of others. In rescuing his jailer, Dirk Willems exemplified altruism. So also did Carl Wilkens and Paul Rusesabagina in Kigali, Rwanda. Wilkens, a Seventh Day Adventist missionary, was living there in 1994 with his family when militia from the Hutu ethnic group began to slaughter members of a minority ethnic group, the Tutsis. The U.S. government, church leaders, and friends all implored Wilkens to leave. He refused. After evacuating his family, and even after every other American had left Kigali, he alone stayed and contested the 800,000-

559

Elsewhere in Kigali, Rusesabagina, a Hutu married to a Tutsi and the acting manager of a luxury hotel, was sheltering more than 1200 terrified Tutsis and moderate Hutus. When international peacekeepers abandoned the city and hostile militia threatened his guests in the “Hotel Rwanda” (as it came to be called in a 2004 movie), the courageous Rusesabagina began cashing in past favors. He bribed the militia and telephoned influential people abroad to exert pressure on local authorities, thereby sparing the lives of the hotel’s occupants from the surrounding chaos. Both Wilkens and Rusesabagina were displaying altruism, an unselfish regard for the welfare of others.

Altruism became a major concern of social psychologists after an especially vile act. On March 13, 1964, a stalker repeatedly stabbed Kitty Genovese, then raped her as she lay dying outside her Queens, New York, apartment at 3:30 a.m. “Oh, my God, he stabbed me!” Genovese screamed into the early morning stillness. “Please help me!” Windows opened and lights went on as neighbors heard her screams. Her attacker fled and then returned to stab and rape her again. Not until he had fled for good did anyone so much as call the police, at 3:50 a.m.

Bystander Intervention

“Probably no single incident has caused social psychologists to pay as much attention to an aspect of social behavior as Kitty Genovese’s murder.”

R. Lance Shotland (1984)

Reflecting on initial reports of the Genovese murder and other such tragedies, most commentators were outraged by the bystanders’ apparent “apathy” and “indifference.” Rather than blaming the onlookers, social psychologists John Darley and Bibb Latané (1968b) attributed their inaction to an important situational factor—

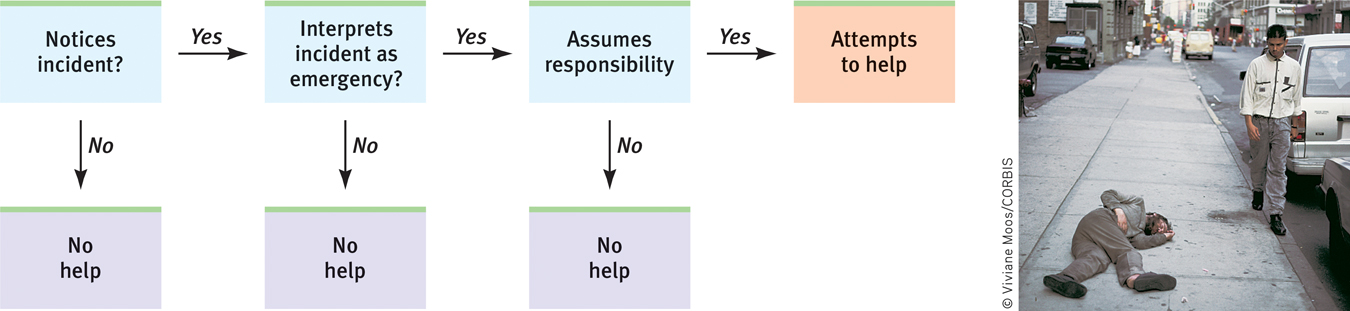

After staging emergencies under various conditions, Darley and Latané assembled their findings into a decision scheme: We will help only if the situation enables us first to notice the incident, then to interpret it as an emergency, and finally to assume responsibility for helping (FIGURE 13.17). At each step, the presence of others can turn us away from the path that leads to helping.

Figure 13.17

Figure 13.17The decision-

Darley and Latané reached their conclusions after interpreting the results of a series of experiments. For example, as students in different laboratory rooms talked over an intercom, the experimenters simulated an emergency. Each student was in a separate cubicle, and only the person whose microphone was switched on could be heard. When his turn came, one student (an accomplice of the experimenters) made sounds as though he were having an epileptic seizure, and he called for help (Darley & Latané, 1968a).

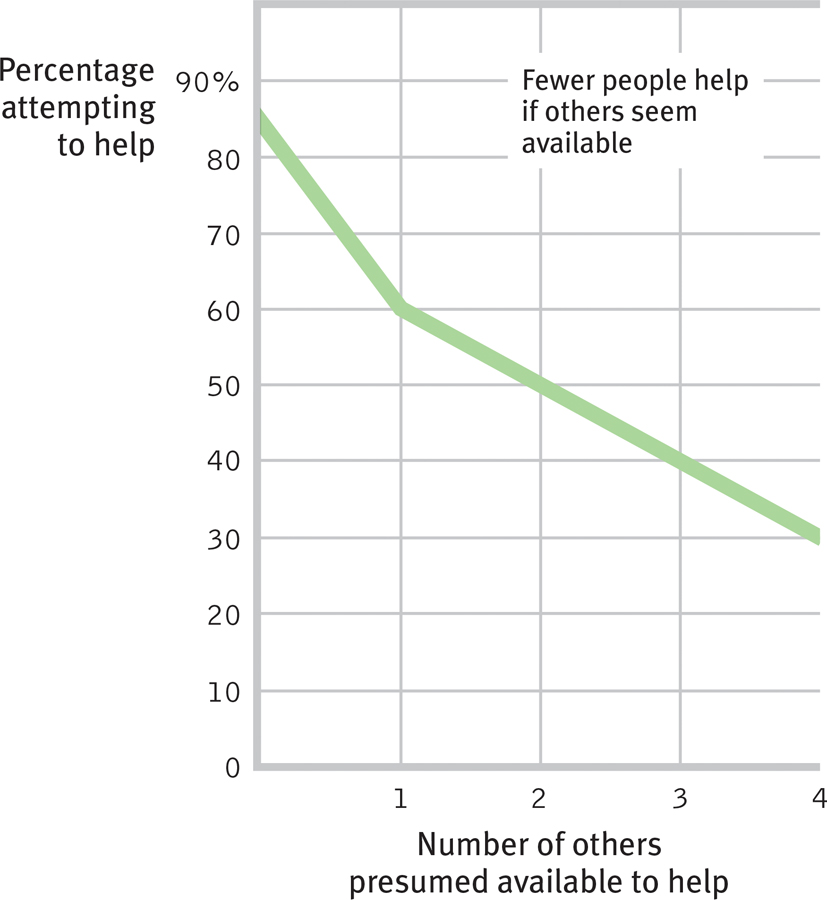

How did the others react? As FIGURE 13.18 below shows, those who believed only they could hear the victim—

Figure 13.18

Figure 13.18Responses to a simulated physical emergency When people thought they alone heard the calls for help from a person they believed to be having an epileptic seizure, they usually helped. But when they thought four others were also hearing the calls, fewer than a third responded. (Data from Darley & Latané, 1968a.)

For a review of research on emergency helping, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: When Will People Help Others?

For a review of research on emergency helping, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: When Will People Help Others?

bystander effect the tendency for any given bystander to be less likely to give aid if other bystanders are present.

560

Hundreds of additional experiments have confirmed this bystander effect. For example, researchers and their assistants took 1497 elevator rides in three cities and “accidentally” dropped coins or pencils in front of 4813 fellow passengers (Latané & Dabbs, 1975). When alone with the person in need, 40 percent helped; in the presence of 5 other bystanders, only 20 percent helped.

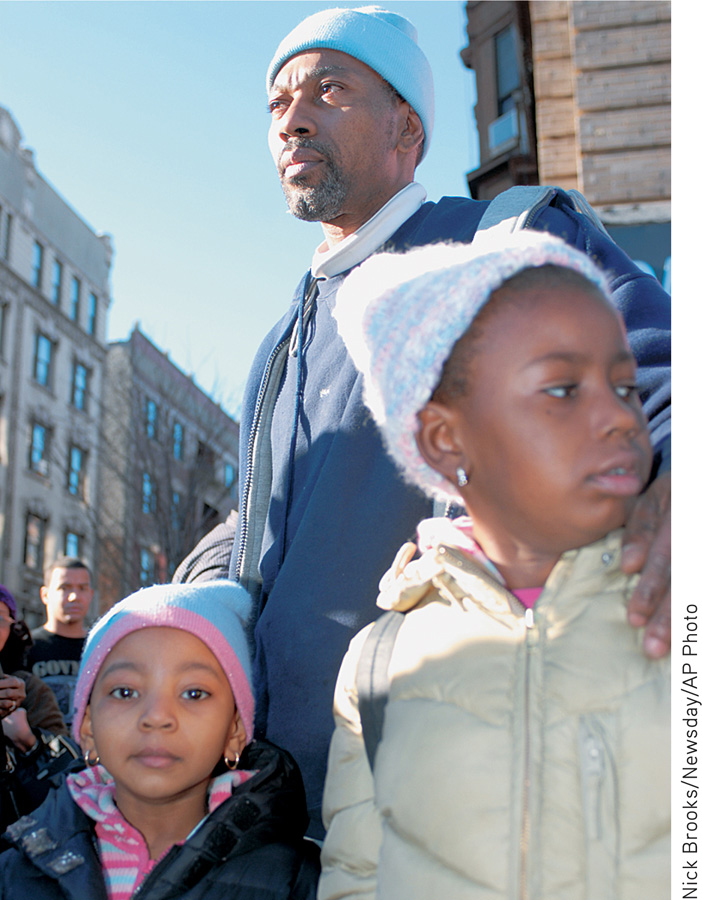

Observations of behavior in thousands of these situations—

- the person appears to need and deserve help.

- the person is in some way similar to us.

- the person is a woman.

- we have just observed someone else being helpful.

- we are not in a hurry.

- we are in a small town or rural area.

- we are feeling guilty.

- we are focused on others and not preoccupied.

- we are in a good mood.

This last result, that happy people are helpful people, is one of the most consistent findings in all of psychology. As poet Robert Browning (1868) observed, “Oh, make us happy and you make us good!” It doesn’t matter how we are cheered. Whether by being made to feel successful and intelligent, by thinking happy thoughts, by finding money, or even by receiving a posthypnotic suggestion, we become more generous and more eager to help (Carlson et al., 1988). And given a feeling of elevation after witnessing or learning of someone else’s self-

So happiness breeds helpfulness. But it’s also true that helpfulness breeds happiness. Making charitable donations activates brain areas associated with reward (Harbaugh et al., 2007). That helps explain a curious finding: People who give money away are happier than those who spend it almost entirely on themselves. In a survey of more than 200,000 people worldwide, people in both rich and poor countries were happier with their lives if they had donated to a charity in the last month (Aknin et al., 2013). Just reflecting on a time when one spent money on others provides most people with a mood boost. And in one experiment, researchers gave people an envelope with cash and instructions either to spend it on themselves or to spend it on others (Dunn et al., 2008, 2013). Which group was happiest at the day’s end? It was, indeed, those assigned to the spend-

561

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why didn’t anybody help Kitty Genovese? What social psychology principle did this incident illustrate?

In the presence of others, an individual is less likely to notice a situation, correctly interpret it as an emergency, and take responsibility for offering help. The Kitty Genovese case demonstrated this bystander effect, as each witness assumed many others were also aware of the event.

social exchange theory the theory that our social behavior is an exchange process, the aim of which is to maximize benefits and minimize costs.

The Norms for Helping

reciprocity norm an expectation that people will help, not hurt, those who have helped them.

13-

Why do we help? One widely held view is that self-

Others believe that we help because we have been socialized to do so, through norms that prescribe how we ought to behave. Through socialization, we learn the reciprocity norm: the expectation that we should return help, not harm, to those who have helped us. In our relations with others of similar status, the reciprocity norm compels us to give (in favors, gifts, or social invitations) about as much as we receive. In one experiment, people who were generously treated also became more likely to be generous to a stranger—

social-

The reciprocity norm kicked in after Dave Tally, a Tempe, Arizona homeless man, found $3300 in a backpack that an Arizona State University student had misplaced on his way to buy a used car (Lacey, 2010). Instead of using the cash for much-

We also learn a social-

People who attend weekly religious services often are admonished to practice the social-

Question

NF8YL0lAk0zVMNnkwGjFgzGY8AAFE1hVGmhU76JjmAAYTIxBfHTOM74/mZmLANUe3nTt0V0uflxk0pT0BcQo1Z4G1CUTy3a9AAlWshKift0YMJCG6qOS3Q9GxKYOdLDIuQRg0wX7jWRPVyQOebFYrekZWWbbrqVCu2iGvDSnMhpaRlktGwPwdbvepKtlVYcJ0k8TQeBU79swMIqA2wuvrX9VU4y7WDQT7o5ZrtfFFcM=562

Peacemaking

We live in surprising times. With astonishing speed, recent democratic movements swept away totalitarian rule in Eastern European and Arab countries, and hopes for a new world order displaced the Cold War chill. And yet, the twenty-

conflict a perceived incompatibility of actions, goals, or ideas.

Elements of Conflict

social trap a situation in which the conflicting parties, by each pursuing their self-

13-

To a social psychologist, a conflict is a perceived incompatibility of actions, goals, or ideas. The elements of conflict are much the same, whether we are speaking of nations at war, cultural groups feuding within a society, or partners sparring in a relationship. In each situation, people become enmeshed in potentially destructive processes that can produce unwanted results. Among these processes are social traps and distorted perceptions.

Social Traps In some situations, we support our collective well-

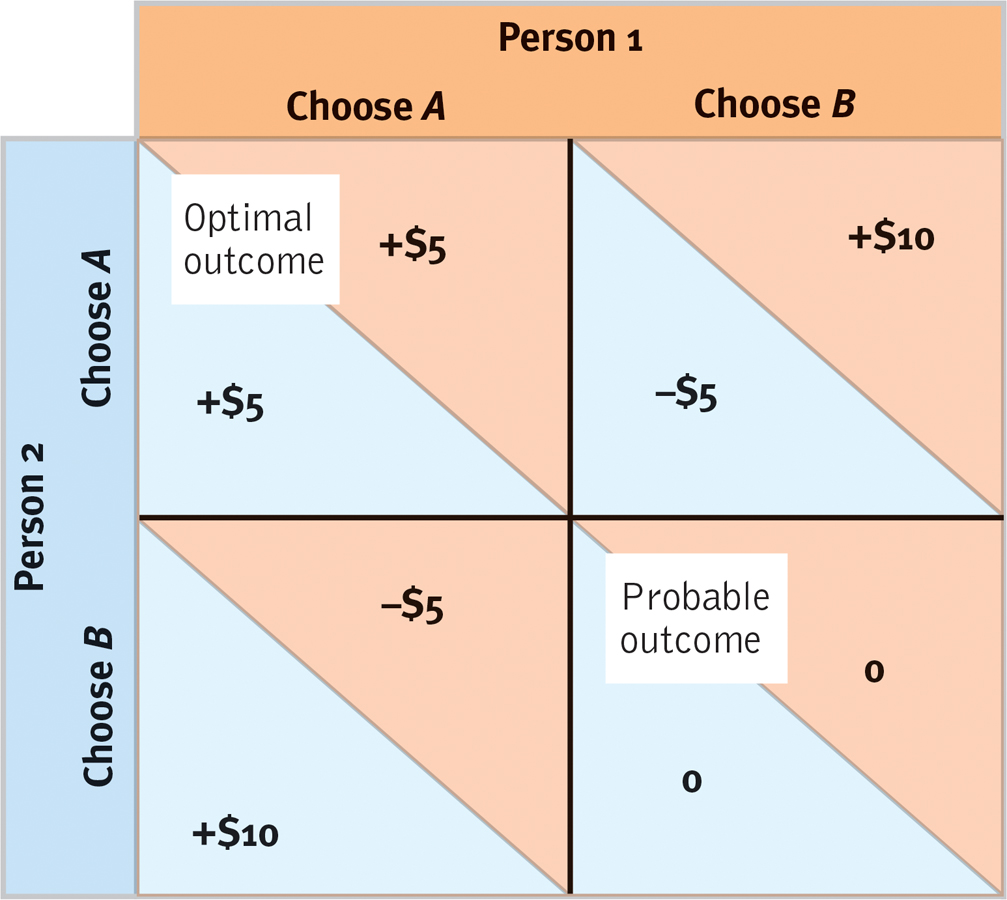

Consider the simple game matrix in FIGURE 13.19, which is similar to those used in experiments with thousands of people. Both sides can win or both can lose, depending on the players’ individual choices. Pretend you are Person 1, and that you and Person 2 will each receive the amount shown after you separately choose either A or B. (You might invite someone to look at the matrix with you and take the role of Person 2.) Which do you choose—

Figure 13.19

Figure 13.19Social-

You and Person 2 are caught in a dilemma. If you both choose A, you both benefit, making $5 each. Neither of you benefits if you both choose B, for neither of you makes anything. Nevertheless, on any single trial you serve your own interests if you choose B: You can’t lose, and you might make $10. But the same is true for the other person. Hence, the social trap: As long as you both pursue your own immediate best interest and choose B, you will both end up with nothing—

563

Many real-

mirror-

self-

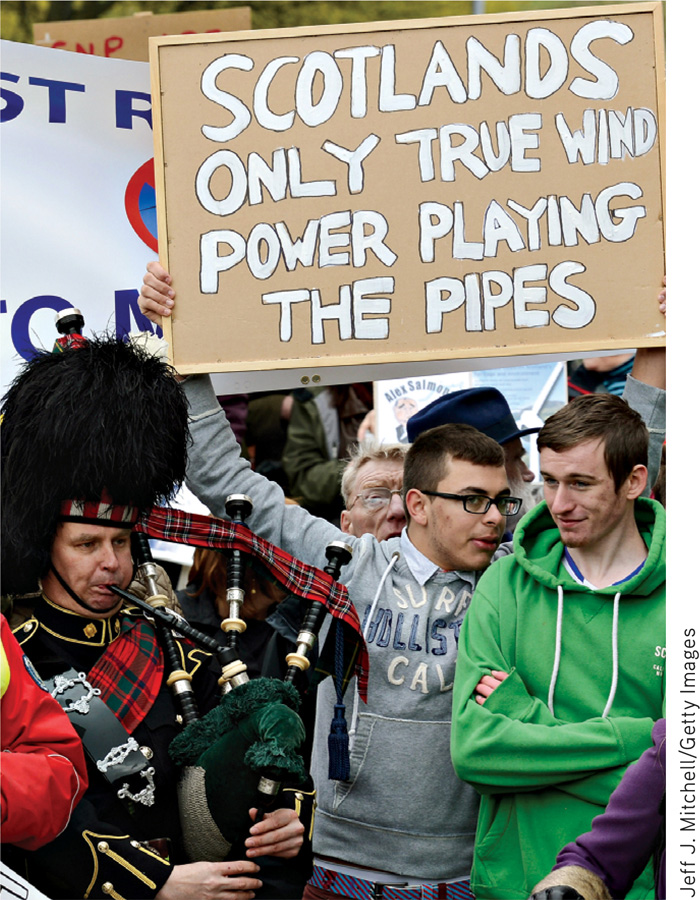

Social traps challenge us to reconcile our right to pursue our personal well-

Enemy Perceptions Psychologists have noted that those in conflict have a curious tendency to form diabolical images of one another. These distorted images are, ironically, so similar that we call them mirror-

Mirror-

Individuals and nations alike tend to see their own actions as responses to provocation, not as the causes of what happens next. Perceiving themselves as returning tit for tat, they often hit back harder, as University College London volunteers did in one experiment (Shergill et al., 2003). Their task: After feeling pressure on their own finger, they were to use a mechanical device to press on another volunteer’s finger. Although told to reciprocate with the same amount of pressure, they typically responded with about 40 percent more force than they had just experienced. Despite seeking only to respond in kind, their touches soon escalated to hard presses, much as when each child after a fight claims that “I just poked him, but he hit me harder.”

Mirror-

564

The point is not that truth must lie midway between two such views; one may be more accurate. The point is that enemy perceptions often form mirror images. Moreover, as enemies change, so do perceptions. In American minds and media, the “bloodthirsty, cruel, treacherous” Japanese of World War II later became our “intelligent, hardworking, self-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why do sports fans tend to feel a sense of satisfaction when their archrival team loses? Why do such feelings, in other settings, make conflict resolution more challenging?

Sports fans may feel a part of an ingroup that sets itself apart from an outgroup (fans of the archrival team). Ingroup bias tends to develop, leading to prejudice and the view that the outgroup “deserves” misfortune. So, the archrival team’s loss may seem justified. In conflicts, this kind of thinking is problematic, especially when each side in the conflict develops mirror-

Promoting Peace

13-

How can we make peace? Can contact, cooperation, communication, and conciliation transform the antagonisms fed by prejudice and conflicts into attitudes that promote peace? Research indicates that, in some cases, they can.

Contact Does it help to put two conflicting parties into close contact? It depends. Negative contact increases disliking (Barlow et al., 2012). But positive contact—

- With cross-

racial contact, South Africans’ interracial attitudes have moved “into closer alignment” (Dixon et al., 2007; Finchilescu & Tredoux, 2010). In South Africa, as elsewhere, the contact effect is somewhat less for lower- status ethnic groups’ views of higher- status groups (Durrheim & Dixon, 2010; Gibson & Claassen, 2010). Still, cross- group friendships have led to more positive attitudes by South African Coloured teens toward minority White teens (Swart et al., 2011). - Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay people are influenced not only by what they know but also by whom they know (Collier et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2009). In surveys, the reason people most often give for becoming more supportive of same-

sex marriage is “having friends, family, or acquaintances who are gay or lesbian” (Pew, 2013). - Friendly contact, say between Blacks and Whites as roommates, improves attitudes toward others of the different race, and even toward other racial outgroups (Gaither & Sommers, 2013; Tausch et al., 2010).

- Even indirect contact with an outgroup member (via story reading or through a friend who has an outgroup friend) has reduced prejudice (Cameron & Rutland, 2006; Pettigrew et al., 2007).

However, contact is not always enough. In most desegregated schools, ethnic groups resegregate themselves in lunchrooms, in classrooms, and elsewhere on school grounds (Alexander & Tredoux, 2010; Clack et al., 2005; Schofield, 1986). People in each group often think that they would welcome more contact with the other group, but they assume the other group does not reciprocate the wish (Richeson & Shelton, 2007). “I don’t reach out to them, because I don’t want to be rebuffed; they don’t reach out to me, because they’re just not interested.” When such mirror-

565

Cooperation To see if enemies could overcome their differences, researcher Muzafer Sherif (1966) set a conflict in motion. He separated 22 Oklahoma City boys into two separate camp areas. Then he had the two groups compete for prizes in a series of activities. Before long, each group became intensely proud of itself and hostile to the other group’s “sneaky,” “smart-

“You cannot shake hands with a clenched fist.”

Indira Gandhi, 1971

superordinate goals shared goals that override differences among people and require their cooperation.

Sherif accomplished this by giving them superordinate goals—shared goals that could be achieved only through cooperation. When he arranged for the camp water supply to “fail,” all 22 boys had to work together to restore the water. To rent a movie in those pre-

A shared predicament likewise had a powerfully unifying effect in the weeks after the 9/11 attacks. Patriotism soared as Americans felt “we” were under attack. Gallup-

At such times, cooperation can lead people to define a new, inclusive group that dissolves their former subgroups (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1999). To accomplish this, you might seat members of two groups not on opposite sides, but alternately around a table. Give them a new, shared name. Have them work together. Then watch “us” and “them” become “we.” After 9/11, one 18-

566

If cooperative contact between rival group members encourages positive attitudes, might this principle bring people together in multicultural schools? Could interracial friendships replace competitive classroom situations with cooperative ones? Could cooperative learning maintain or even enhance student achievement? Experiments with adolescents from 11 countries confirm that, in each case, the answer is Yes (Roseth et al., 2008). In the classroom as in the sports arena, members of interracial groups who work together on projects typically come to feel friendly toward one another. Knowing this, thousands of teachers have made interracial cooperative learning part of their classroom experience.

The power of cooperative activity to make friends of former enemies has led psychologists to urge increased international exchange and cooperation. Some experiments have found that just imagining the shared threat of global climate change reduces international hostilities (Pyszczynski et al., 2012). From adjacent Brazilian tribes to European countries, formerly conflicting groups have managed to build interconnections, interdependence, and a shared social identity as they seek common goals (Fry, 2012). As we engage in mutually beneficial trade, as we work to protect our common destiny on this fragile planet, and as we become more aware that our hopes and fears are shared, we can transform misperceptions that feed conflict into feelings of solidarity based on common interests.

Communication When real-

GRIT Graduated and Reciprocated Initiatives in Tension-

567

Conciliation Understanding and cooperative resolution are most needed, yet least likely, in times of anger or crisis (Bodenhausen et al., 1994; Tetlock, 1988). When conflicts intensify, images become more stereotyped, judgments more rigid, and communication more difficult, or even impossible. Each party is likely to threaten, coerce, or retaliate. In the weeks before the 1990 Gulf War, the first President George Bush threatened, in the full glare of publicity, to “kick Saddam’s ass.” Saddam Hussein communicated in kind, threatening to make Americans “swim in their own blood.”

Under such conditions, is there an alternative to war or surrender? Social psychologist Charles Osgood (1962, 1980) advocated a strategy of Graduated and Reciprocated Initiatives in Tension-

In laboratory experiments, small conciliatory gestures—

As working toward shared goals reminds us, we are more alike than different. Civilization advances not by conflict and cultural isolation, but by tapping the knowledge, the skills, and the arts that are each culture’s legacy to the whole human race. Thanks to cultural sharing, every modern society is enriched by a cultural mix (Sowell, 1991). We have China to thank for paper and printing and for the magnetic compass that opened the great explorations. We have Egypt to thank for trigonometry. We have the Islamic world and India’s Hindus to thank for our Arabic numerals. While celebrating and claiming these diverse cultural legacies, we can also welcome the enrichment of today’s social diversity. We can view ourselves as instruments in a human orchestra. And we—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are some ways to reconcile conflicts and promote peace?

Peacemakers should encourage equal-

568