15.1 Introduction to Psychological Disorders

Most people would agree that someone who is too depressed to get out of bed for weeks at a time has a psychological disorder. But what about those who, having experienced a loss, are unable to resume their usual social activities? Where should we draw the line between sadness and depression? Between zany creativity and bizarre irrationality? Between normality and abnormality? Let’s start with these questions:

“Who in the rainbow can draw the line where the violet tint ends and the orange tint begins? Distinctly we see the difference of the colors, but where exactly does the one first blendingly enter into the other? So with sanity and insanity.”

Herman Melville, Billy Budd, Sailor, 1924

- How should we define psychological disorders?

- How should we understand disorders? How do underlying biological factors contribute to disorder? How do troubling environments influence our well-

being? And how do these effects of nature and nurture interact? - How should we classify psychological disorders? And can we do so in a way that allows us to help people without stigmatizing them with labels?

- What do we know about rates of psychological disorders? How many people have them? Who is vulnerable, and when?

Defining Psychological Disorders

psychological disorder a syndrome marked by a clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior.

15-

A psychological disorder is a syndrome (collection of symptoms) marked by a “clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Disturbed, or dysfunctional thoughts, emotions, or behaviors are maladaptive—they interfere with normal day-

Distress often accompanies dysfunctional behaviors. Marc, Greta, and Stuart were all distressed by their behaviors or emotions.

Over time, definitions of what makes for a “significant disturbance” have varied. From 1952 through December 9, 1973, homosexuality was classified as a psychological disorder. By day’s end on December 10, it was not. The American Psychiatric Association made this change because more and more of its members no longer viewed same-

Question

eRo4ITxDks8pEHsa6fSlZE0QUTO2Ft4DzZw/+/LRip+HQ1PZuQOj0J9xymLRAd94tdfItcpgUCVnP5EPQd+PknJ51Unlb1Y1XVU7K759ThHjPvA2IHG/9AZP7CsQXoG2b0U7ZCt3Z4yPFyf/TdrPuMJ7etk78KeV/rxDDjCUCXDrSUkkp/LGkdkIUhfcLn/8Dw/yVtDfUYpkZMpzL/jV5IQ2CDwDvYSe+vf9DtLbbVNyv880TI4D8trSmckF5IYWnO/kzKb70DDgHpZq611

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- A lawyer is distressed by feeling the need to wash his hands 100 times a day. He has no time left to meet with clients, and his colleagues are wondering about his competence. His behavior would probably be labeled disordered, because it is ______________ that is, it interferes with his day-

to- day life.

maladaptive

Understanding Psychological Disorders

15-

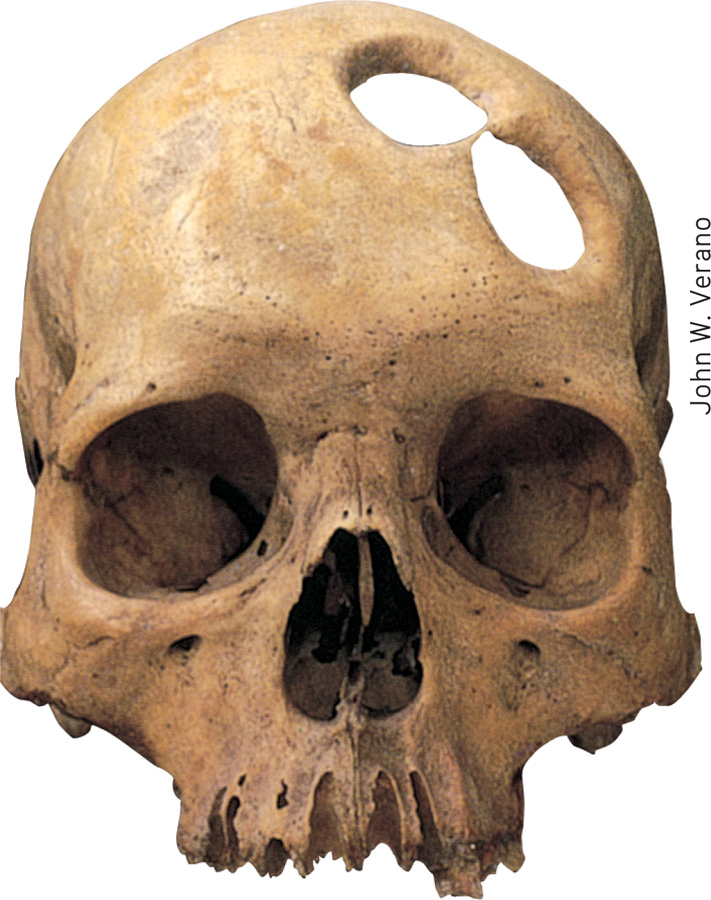

The way we view a problem influences how we try to solve it. In earlier times, people often viewed strange behaviors as evidence that strange forces—

The Medical Model

Brutal treatments may worsen, rather than improve, mental health. Reformers, such as Philippe Pinel (1745–

medical model the concept that diseases, in this case psychological disorders, have physical causes that can be diagnosed, treated, and, in most cases, cured, often through treatment in a hospital.

612

By the 1800s, the discovery that syphilis infects the brain and distorts the mind drove further gradual reform. Hospitals replaced asylums, and the medical model of mental disorders was born. This model is reflected in the terms we still use today. We speak of the mental health movement: A mental illness (also called a psychopathology) needs to be diagnosed on the basis of its symptoms. It needs to be treated through therapy, which may include time in a psychiatric hospital.

The medical perspective has gained credibility from recent discoveries that genetically influenced abnormalities in brain structure and biochemistry contribute to many disorders. But as we will see, psychological factors, such as chronic or traumatic stress, also play an important role.

The Biopsychosocial Approach

To call psychological disorders “sicknesses” tilts research heavily toward the influence of biology and away from the influence of our personal histories and social and cultural surroundings. But in the study of disorders, as in so many other areas, we must remember that our behaviors, our thoughts, and our feelings are formed by the interaction of biological, psychological, and social-

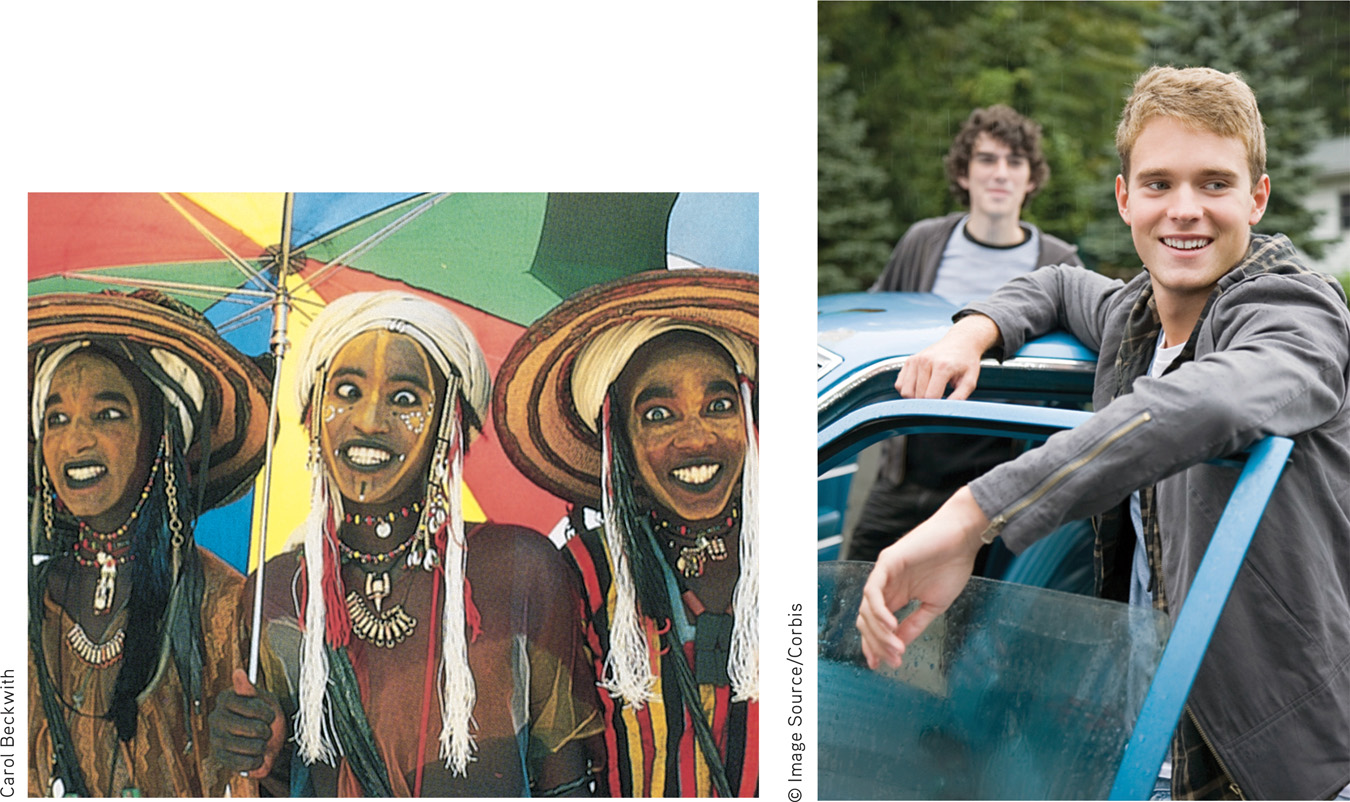

Increasingly, North America’s disorders, along with McDonald’s and MTV, have spread across the globe (Watters, 2010).

Some disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia, occur worldwide. From Asia to Africa and across the Americas, schizophrenia’s symptoms often include irrationality and incoherent speech. Other disorders tend to be associated with specific cultures. In Malaysia, amok describes a sudden outburst of violent behavior (thus the English phrase “run amok”). Latin America lays claim to susto, a condition marked by severe anxiety, restlessness, and a fear of black magic. In Japanese culture, people may experience taijin kyofusho—social anxiety about their appearance, combined with a readiness to blush and a fear of eye contact. The eating disorders anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa occur mostly in food-

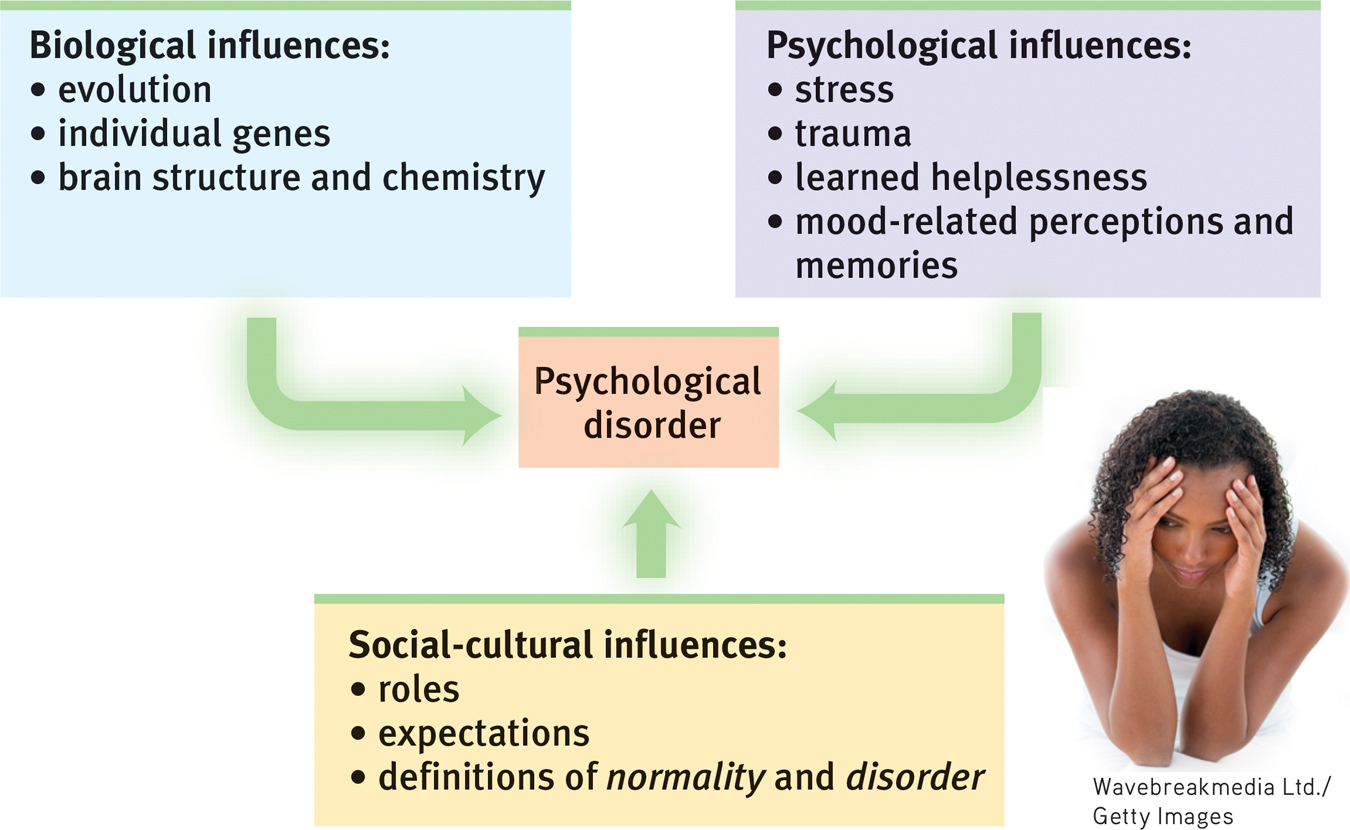

Disorders reflect genetic predispositions and physiological states, inner psychological dynamics, and social and cultural circumstances. The biopsychosocial approach emphasizes that mind and body are inseparable (FIGURE 15.1). Negative emotions contribute to physical illness, and physical abnormalities contribute to negative emotions. Epigenetics, the study of how nurture shapes nature, also informs our understanding of disorders (Powledge, 2011). Genes and environment are not the whole story, as we’ve seen in other chapters. It turns out our environment can affect whether a gene is expressed or not, and thus affect the development of various psychological disorders.

Figure 15.1

Figure 15.1The biopsychosocial approach to psychological disorders Today’s psychology studies how biological, psychological, and social-

epigenetics the study of environmental influences on gene expression that occur without a DNA change.

613

For example, even identical twins (with identical genes) do not share the same risks of developing psychological disorders. They are more likely, but not always destined, to develop the same disorders. Their varying environmental factors influence whether certain culprit genes are expressed.

Question

x3mTkUGTskOvnQVEYur59KKFD3JsChPZMPBdfjsDi9NJLYj0XcWa9wSIK0YDWbQvCM2YOUUO+Dd2SS8hk7J4SMkXKIghHKs7kJsvaVrItW10W/CKWal4HZvlHnLCJ1dTOGm1GPlMxar3Qlzl7jDWgOEbcTS/YJojm12puf1IH2+efKJ1xRj5aCw9J2KgGbMMVB8p3vMmOCi9cw0P8XCz1eOU2Ydapx6+1zysMoHmOg07jtcdVJMkeySkTw9z1OkZHciWfxKm843+Oj+6TQ5hxdRldLyqMzzMAlrJZTwOvNIImOjKWywzx7slS+qaB+qlpslK/eiUnKk=RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Are psychological disorders universal, or are they culture-

specific? Explain with examples.

Some psychological disorders are culture-

- What is the biopsychosocial approach, and why is it important in our understanding of psychological disorders?

Biological, psychological, and social-

Classifying Disorders—and Labeling People

15-

In biology, classification creates order. To classify an animal as a “mammal” says a great deal—

But diagnostic classification gives more than a thumbnail sketch of a person’s disordered behavior, thoughts, or feelings. In psychiatry and psychology, classification also aims to

- predict the disorder’s future course.

- suggest appropriate treatment.

- prompt research into its causes.

To study a disorder, we must first name and describe it.

A book of case illustrations accompanying the previous DSM edition provided several examples for this chapter.

DSM-

The most common tool for describing disorders and estimating how often they occur is the American Psychiatric Association’s 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, now in its fifth edition (DSM-

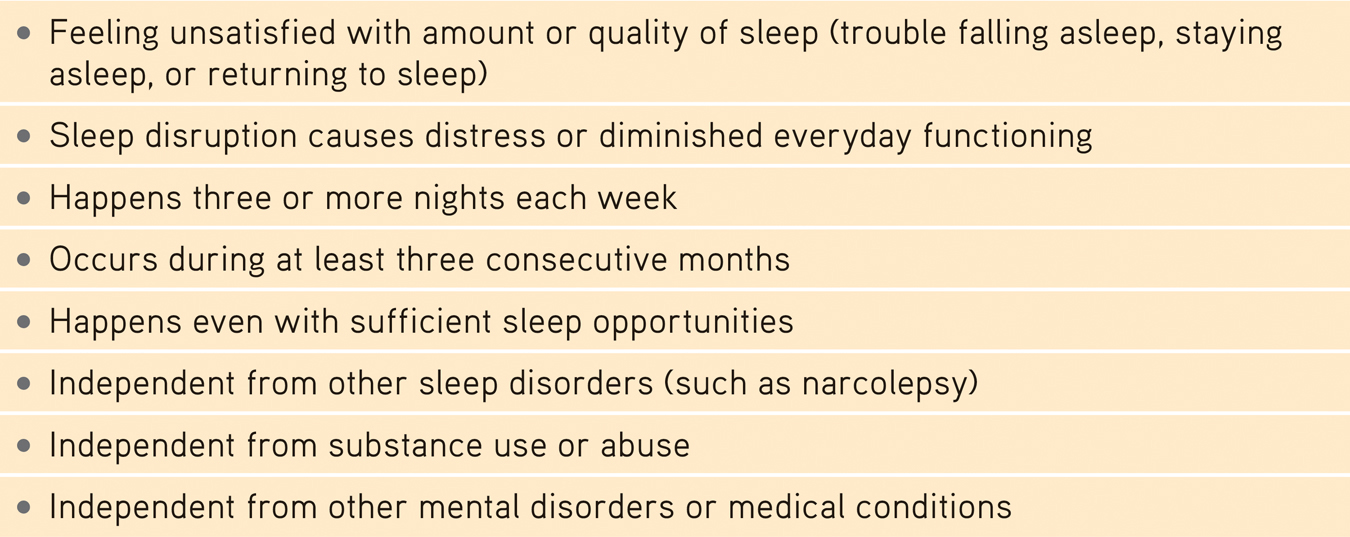

Table 15.1

Table 15.1Insomnia Disorder

614

In the DSM-

Some of the new or altered diagnoses are controversial. Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder is a new DSM-

Real-

Critics have long faulted the DSM for casting too wide a net and bringing “almost any kind of behavior within the compass of psychiatry” (Eysenck et al., 1983). Some now worry that the DSM-

Other critics register a more basic complaint—

The biasing power of labels was clear in a now-

Should we be surprised? As one psychiatrist noted, if someone swallows blood, goes to an emergency room, and spits it up, should we fault the doctor for diagnosing a bleeding ulcer? Surely not. But what followed the Rosenhan study diagnoses was startling. Until being released an average of 19 days later, those eight “patients” showed no other symptoms. Yet after analyzing their (quite normal) life histories, clinicians were able to “discover” the causes of their disorders, such as having mixed emotions about a parent. Even routine note-

Labels matter. In another study, people watched videotaped interviews. If told the interviewees were job applicants, the viewers perceived them as normal (Langer et al., 1974, 1980). Other viewers who were told they were watching psychiatric or cancer patients perceived the same interviewees as “different from most people.” Therapists who thought they were watching an interview of a psychiatric patient perceived him as “frightened of his own aggressive impulses,” a “passive, dependent type,” and so forth. A label can, as Rosenhan discovered, have “a life and an influence of its own.”

615

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

ADHD—

attention-

15-

Eight-

If taken for a psychological evaluation, Todd may be diagnosed with attention-

To skeptics, being distractible, fidgety, and impulsive sounds like a “disorder” caused by a single genetic variation: a Y chromosome (the male sex chromosome). And sure enough, ADHD is diagnosed three times more often in boys than in girls. Children who are “a persistent pain in the neck in school” are often diagnosed with ADHD and given powerful prescription drugs (Gray, 2010). Minority youth less often receive an ADHD diagnosis than do Caucasian youth, but this difference has shrunk as minority ADHD diagnoses have increased (Getahun et al., 2013).

The problem may reside less in the child than in today’s abnormal environment that forces children to do what evolution has not prepared them to do—

Rates of medication for presumed ADHD vary by age, sex, and location. Prescription drugs are more often given to teens than to younger children. Boys are nearly three times more likely to receive them than are girls. And location matters. Among 4-

Not everyone agrees that ADHD is being overdiagnosed. Some argue that today’s more frequent diagnoses reflect increased awareness of the disorder, especially in those areas where rates are highest. They also note that diagnoses can be inconsistent—

What, then, is known about ADHD’s causes? It is not caused by too much sugar or poor schools. There is mixed evidence suggesting that extensive TV watching and video gaming are associated with reduced cognitive self-

The bottom line: Extreme inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity can derail social, academic, and vocational achievements, and these symptoms can be treated with medication and other therapies. But the debate continues over whether normal high energy is too often diagnosed as a psychiatric disorder, and whether there is a cost to the long-

616

“My sister suffers from a bipolar disorder and my nephew from schizoaffective disorder. There has, in fact, been a lot of depression and alcoholism in my family and, traditionally, no one ever spoke about it. It just wasn’t done. The stigma is toxic.”

Actress Glenn Close, “Mental Illness: The Stigma of Silence,” 2009

Labels also have power outside the laboratory. Getting a job or finding a place to rent can be a challenge for people recently released from a mental hospital. Label someone as “mentally ill” and people may fear them as potentially violent (see Thinking Critically About: Are People With Psychological Disorders Dangerous?) Such negative reactions may fade as people better understand that many psychological disorders involve diseases of the brain, not failures of character (Solomon, 1996). Public figures have helped foster this new understanding by speaking openly about their own struggles with disorders such as depression and substance abuse. The more contact we have with people with disorders, the more accepting our attitudes are (Kolodziej & Johnson, 1996).

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Are People With Psychological Disorders Dangerous?

15-

September 16, 2013, started like any other Monday at Washington, DC’s, Navy Yard, with people arriving early to begin work. Then government contractor Aaron Alexis parked his car, entered the building, and began shooting people. An hour later, 13 people were dead, including Alexis. Reports later confirmed that Alexis had a history of mental illness. Before the shooting, he had stated that an “ultra low frequency attack is what I’ve been subject to for the last three months. And to be perfectly honest, that is what has driven me to this.” This devastating mass shooting, like the one in a Connecticut elementary school in 2012 and many others since then, reinforced public perceptions that people with psychological disorders pose a threat (Jorm et al., 2012). After the 2012 slaughter, New York’s governor declared, “People who have mental issues should not have guns” (Kaplan & Hakim, 2013).

Does scientific evidence support the governor’s statement? If disorders actually increase the risk of violence, then denying people with psychological disorders the right to bear arms might reduce violent crimes. But real life tells a different story. The vast majority of violent crimes are committed by people with no diagnosed disorder (Fazel & Grann, 2006; Walkup & Rubin, 2013).

People with disorders are more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence (Marley & Bulia, 2001). According to the U.S. Surgeon General’s Office (1999, p. 7), “There is very little risk of violence or harm to a stranger from casual contact with an individual who has a mental disorder.” People with mental illness commit proportionately little gun violence. The bottom line: Focusing gun restrictions only on mentally ill people will likely not reduce gun violence (Friedman, 2012).

If mental illness is not a good predictor of violence, what is? Better predictors are a history of violence, use of alcohol or drugs, and access to a gun. The mass-

Mental disorders seldom lead to violence, and clinical prediction of violence is unreliable. What, then, are the triggers for the few people with psychological disorders who do commit violent acts? For some, the trigger is substance abuse. For others, like the Navy Yard shooter, it’s threatening delusions and hallucinated voices that command them to act (Douglas et al., 2009; Elbogen & Johnson, 2009; Fazel et al., 2009, 2010). Whether people with mental disorders who turn violent should be held responsible for their behavior remains controversial. U.S. President Ronald Reagan’s near-

Which decision was correct? The first two, which blamed Loughner’s “madness” for clouding his judgment? Or the final one, which decided that he should be held responsible for the acts he committed? As we come to better understand the biological and environmental bases for all human behavior, from generosity to vandalism, when should we—

617

“What’s the use of their having names,” the Gnat said, “if they won’t answer to them?”

“No use to them,” said Alice; “but it’s useful to the people that name them, I suppose.”

Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-

Despite their risks, diagnostic labels have benefits. Mental health professionals use labels to communicate about their cases, to comprehend the underlying causes, and to discern effective treatment programs. Researchers use labels when discussing work that explores the causes and treatments of disorders. Clients are often relieved to learn that the nature of their suffering has a name, and that they are not alone in experiencing this collection of symptoms.

Question

dN+TNeXHbGGywjBeKpWT91NR7aABsjotly20+IcF6/AeCUBLjPCVCNxzkuLqKrwwloMgnmta9Yq7/1kRXEzJnCvjza1U3HMHpVzlV0pb44HVtsYQ2v1WDlAw5SVTewwJJ0NBmstRP7CIXRheKyCkKi/pUmUg2P4TFLxH6X42zJxytEXPWfewHGOwtAtgTCSSDzJSusWtfME8dOAPdfO6qEdXsVTwPFGMKKDLm5zwV//SSu65mTylUZu2Xn/wmOdavFLcrA== To test your ability to form diagnoses, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classifying Disorders.

To test your ability to form diagnoses, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Classifying Disorders.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the value, and what are the dangers, of labeling individuals with disorders?

Therapists and others use disorder labels to communicate with one another using a common language, and to share concepts during research. Clients may benefit from knowing that they are not the only ones with these symptoms. The dangers of labeling people are that (1) people may begin to act as they have been labeled, and (2) the labels can trigger assumptions that will change our behavior toward those we label.

Rates of Psychological Disorders

15-

Who is most vulnerable to psychological disorders? At what times of life? To answer such questions, various countries have conducted lengthy structured interviews with representative samples of thousands of their citizens. After asking hundreds of questions that probed for symptoms—

How many people have, or have had, a psychological disorder? More than most of us suppose:

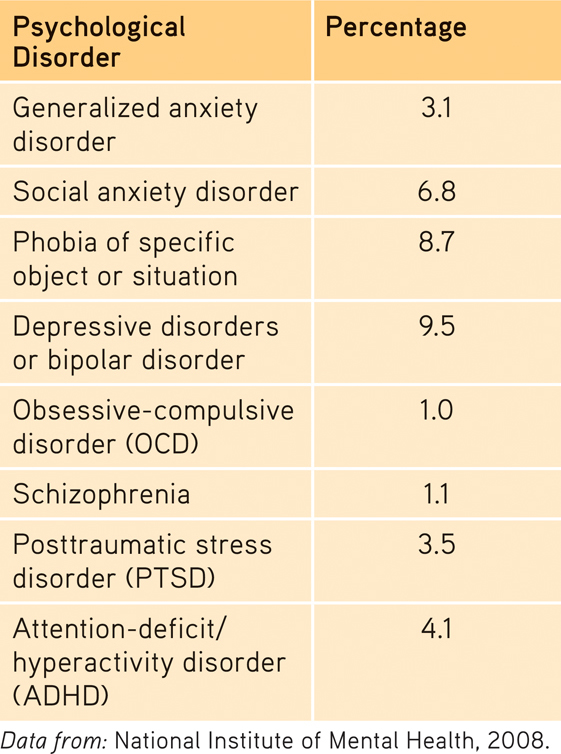

- The U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (2008, based on Kessler et al., 2005) has estimated that just over 1 in 4 adult Americans “suffer from a diagnosable mental disorder in a given year” (TABLE 15.2).

Table 15.2

Table 15.2

Percentage of Americans Reporting Selected Psychological Disorders in the Past Year - A large-

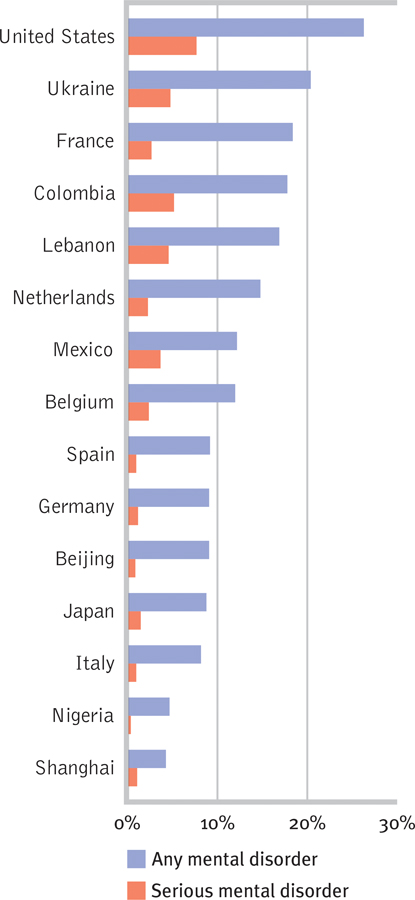

scale World Health Organization (2004a) study— based on 90- minute interviews of 60,463 people— estimated the number of prior- year mental disorders in 20 countries. As FIGURE 15.2 below displays, the lowest rate of reported mental disorders was in Shanghai, the highest rate in the United States. Moreover, immigrants to the United States from Mexico, Africa, and Asia averaged better mental health than their U.S. counterparts with the same ethnic heritage (Breslau et al., 2007; Maldonado- Molina et al., 2011). For example, compared with people who have recently immigrated from Mexico, Mexican- Americans born in the United States are at greater risk of mental disorder— a phenomenon known as the immigrant paradox (Schwartz et al., 2010).

Figure 15.2

Figure 15.2

Prior-year prevalence of disorders in selected areas From World Health Organization (WHO, 2004a) interviews in 20 countries.

618

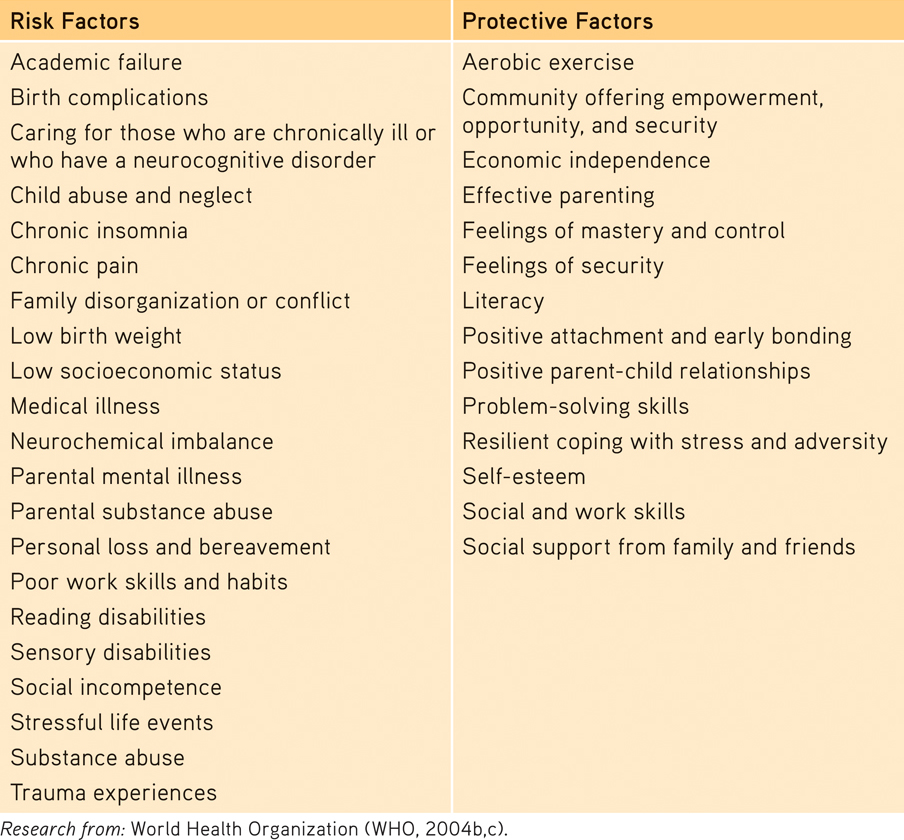

What increases vulnerability to mental disorders? As TABLE 15.3 indicates, there is a wide range of risk and protective factors for mental disorders. But one predictor of mental disorder, poverty, crosses ethnic and gender lines. The incidence of serious psychological disorders has been doubly high among those below the poverty line (CDC, 1992). Like so many other correlations, the poverty-

Table 15.3

Table 15.3Risk and Protective Factors for Mental Disorders

In one natural experiment on the poverty-

At what times of life do disorders strike? Usually by early adulthood. “Over 75 percent of our sample with any disorder had experienced [their] first symptoms by age 24,” reported Lee Robins and Darrel Regier (1991, p. 331). Among the earliest to appear are the symptoms of antisocial personality disorder (median age 8) and of phobias (median age 10). Alcohol use disorder, obsessive-

619

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the relationship between poverty and psychological disorders?

Poverty-