15.5 Dissociative, Personality, and Eating Disorders

Please continue to the next section.

Dissociative Disorders

dissociative disorders controversial, rare disorders in which conscious awareness becomes separated (dissociated) from previous memories, thoughts, and feelings.

15-

Among the most bewildering disorders are the rare dissociative disorders, in which a person’s conscious awareness dissociates (separates) from painful memories, thoughts, and feelings. The result may be a fugue state, a sudden loss of memory or change in identity, often in response to an overwhelmingly stressful situation. Such was the case for one Vietnam veteran who was haunted by his comrades’ deaths, and who had left his World Trade Center office shortly before the 9/11 attack. Later, he disappeared on the way to work. Six months later, when he was discovered in a Chicago homeless shelter, he reported no memory of his identity or family (Stone, 2006).

647

dissociative identity disorder (DID) a rare dissociative disorder in which a person exhibits two or more distinct and alternating personalities. Formerly called multiple personality disorder.

Dissociation itself is not so rare. Any one of us may have a sense of being unreal, of being separated from our body, of watching ourselves as if in a movie. Sometimes we may say, “I was not myself at the time.” Perhaps you can recall getting up to go somewhere and ending up at some unintended location while your mind was preoccupied. Or perhaps you can play a well-

Dissociative Identity Disorder

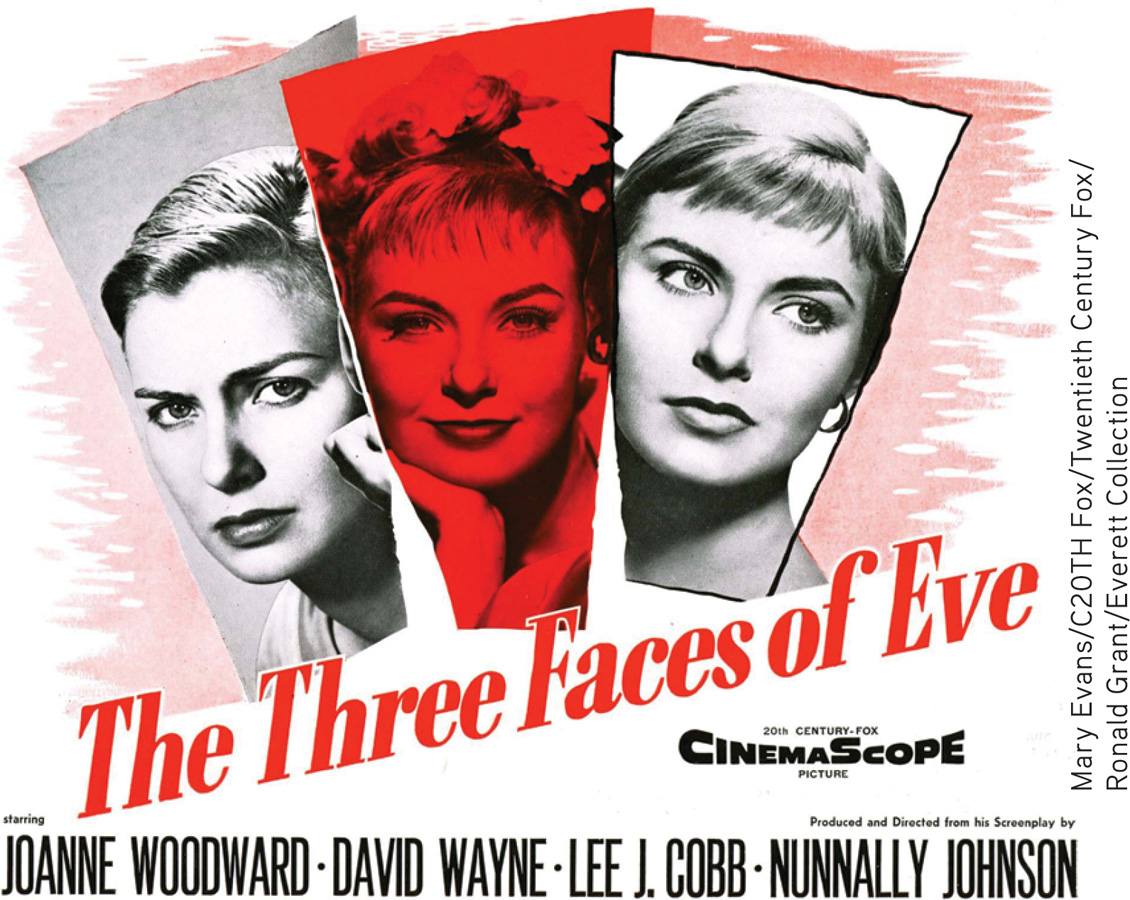

A massive dissociation of self from ordinary consciousness occurs in dissociative identity disorder (DID), in which two or more distinct identities—

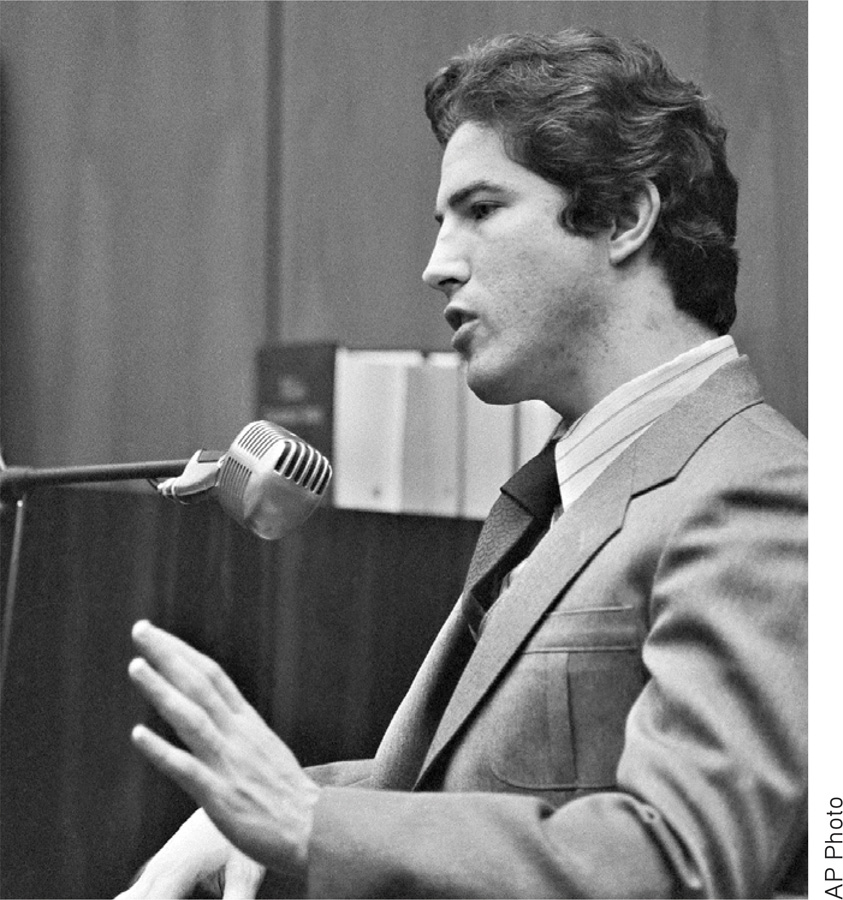

People diagnosed with DID (formerly called multiple personality disorder) are rarely violent. But cases have been reported of dissociations into a “good” and a “bad” (or aggressive) personality—

Speaking as Steve, Bianchi stated that he hated Ken because Ken was nice and that he (Steve), aided by a cousin, had murdered women. He also claimed Ken knew nothing about Steve’s existence and was innocent of the murders. Was Bianchi’s second personality a trick, simply a way of disavowing responsibility for his actions? Indeed, Bianchi—

Understanding Dissociative Identity Disorder

Skeptics have raised serious concerns about DID. First, instead of being a true disorder, could DID be an extension of our normal capacity for personality shifts? Nicholas Spanos (1986, 1994, 1996) asked college students to pretend they were accused murderers being examined by a psychiatrist. Given the same hypnotic treatment Bianchi received, most spontaneously expressed a second personality. This discovery made Spanos wonder: Are dissociative identities simply a more extreme version of our capacity to vary the “selves” we present—

“Pretense may become reality.”

Chinese proverb

Skeptics also find it suspicious that the disorder has such a short and localized history. Between 1930 and 1960, the number of North American DID diagnoses averaged 2 per decade. By the 1980s, when the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) contained the first formal code for this disorder, the number exploded to more than 20,000 (McHugh, 1995a). The average number of displayed personalities also mushroomed—

648

Such findings, skeptics note, point to a cultural phenomenon—

Other researchers and clinicians believe DID is a real disorder. They find support for this view in the distinct body and brain states associated with differing personalities (Putnam, 1991). Handedness sometimes switches with personality (Henninger, 1992). Shifts in visual acuity and eye-

“Though this be madness, yet there is method in ’t.”

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1600

Both the psychodynamic and learning perspectives have interpreted DID symptoms as ways of coping with anxiety. Some psychodynamic theorists see them as defenses against the anxiety caused by the eruption of unacceptable impulses. In this view, a second personality enables the discharge of forbidden impulses. Learning theorists see dissociative disorders as behaviors reinforced by anxiety reduction.

Some clinicians include dissociative disorders under the umbrella of posttraumatic stress disorder—

So the debate continues. On one side are those who believe multiple personalities are the desperate efforts of people trying to detach from a horrific existence. On the other are the skeptics who think DID is a condition constructed out of the therapist-

Question

n2O82VsnmmuO7BrkvRZEqqKPYZcPzOv4iXXalD2XzmqQIStAAD5jy06erBVU5DOQCIBbG2yBfSyrusNVCvFaixmt+t2ERELgSeygt7tRxFkeSyrTwaM7pSsw0Hpd4K1FCTqTnsSQ5c/YwZPuCJH5y9RkFqlYiyq4212MhBP25ejpuSShIrSBzGtv3MbjzUx05ZFgHKVLkEglVLp9JUrYkiHB9K1kZAzh6zA+hDtF9v3Pw3biDZxbcpxDw3dAi0GKNFc0PVSp+yEHOj/PPt/ORy5UkXSg+8+SBMTOfO6lbEJi/BQx2ScsscjuEhXFw+JkESONHw==RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The psychodynamic and learning perspectives agree that dissociative identity disorder symptoms are ways of dealing with anxiety. How do their explanations differ?

The psychodynamic explanation of DID symptoms is that they are defenses against anxiety generated by unacceptable urges. The learning perspective attempts to explain these symptoms as behaviors that have been reinforced by relieving anxiety in the past.

649

Personality Disorders

personality disorders inflexible and enduring behavior patterns that impair social functioning.

15-

The disruptive, inflexible, and enduring behavior patterns of personality disorders interfere with social functioning. These disorders tend to form three clusters, characterized by

- anxiety, such as a fearful sensitivity to rejection that predisposes the withdrawn avoidant personality disorder.

- eccentric or odd behaviors, such as the emotionless disengagement of schizotypal personality disorder.

- dramatic or impulsive behaviors, such as the attention-

getting borderline personality disorder, the self- focused and self- inflating narcissistic personality disorder, and the callous, and sometimes dangerous, antisocial personality disorder.

antisocial personality disorder a personality disorder in which a person (usually a man) exhibits a lack of conscience for wrongdoing, even toward friends and family members; may be aggressive and ruthless or a clever con artist.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

A person with antisocial personality disorder is typically a male whose lack of conscience becomes plain before age 15, as he begins to lie, steal, fight, or display unrestrained sexual behavior (Cale & Lilienfeld, 2002). About half of such children become antisocial adults—

Despite their remorseless and sometimes criminal behavior, criminality is not an essential component of antisocial behavior (Skeem & Cooke, 2010). Moreover, many criminals do not fit the description of antisocial personality disorder. Why? Because they actually show responsible concern for their friends and family members.

Antisocial personalities behave impulsively, and then feel and fear little (Fowles & Dindo, 2009). Their impulsivity can have violent, horrifying consequences (Camp et al., 2013). Consider the case of Henry Lee Lucas. He killed his first victim when he was 13. He felt little regret then or later. He confessed that, during his 32 years of crime, he had brutally beaten, suffocated, stabbed, shot, or mutilated some 360 women, men, and children. For the last six years of his reign of terror, Lucas teamed with Ottis Elwood Toole, who reportedly slaughtered about 50 people he “didn’t think was worth living anyhow” (Darrach & Norris, 1984).

Understanding Antisocial Personality Disorder

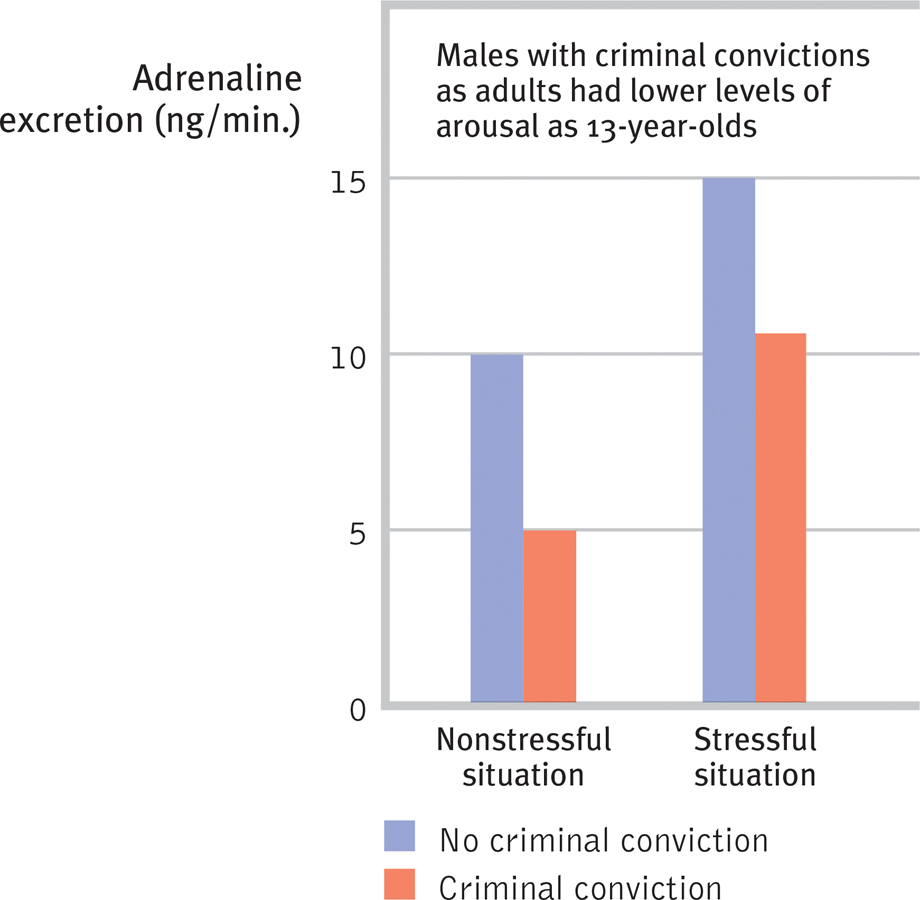

Antisocial personality disorder is woven of both biological and psychological strands. Twin and adoption studies reveal that biological relatives of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies are at increased risk for antisocial behavior (Frisell et al., 2012; Tuvblad et al., 2011). No single gene codes for a complex behavior such as crime. Molecular geneticists have, however, identified some specific genes that are more common in those with antisocial personality disorder (Gunter et al., 2010). The genetic vulnerability of people with antisocial and unemotional tendencies appears as a fearless approach to life. Awaiting aversive events, such as electric shocks or loud noises, they show little autonomic nervous system arousal (Hare, 1975; van Goozen et al., 2007). Long-

Figure 15.12

Figure 15.12Cold-

650

Traits such as fearlessness and dominance can be adaptive. In fact, some argue that psychopaths and heroes are twigs off the same branch (Smith et al., 2013). If channeled in more productive directions, fearlessness may lead to star-

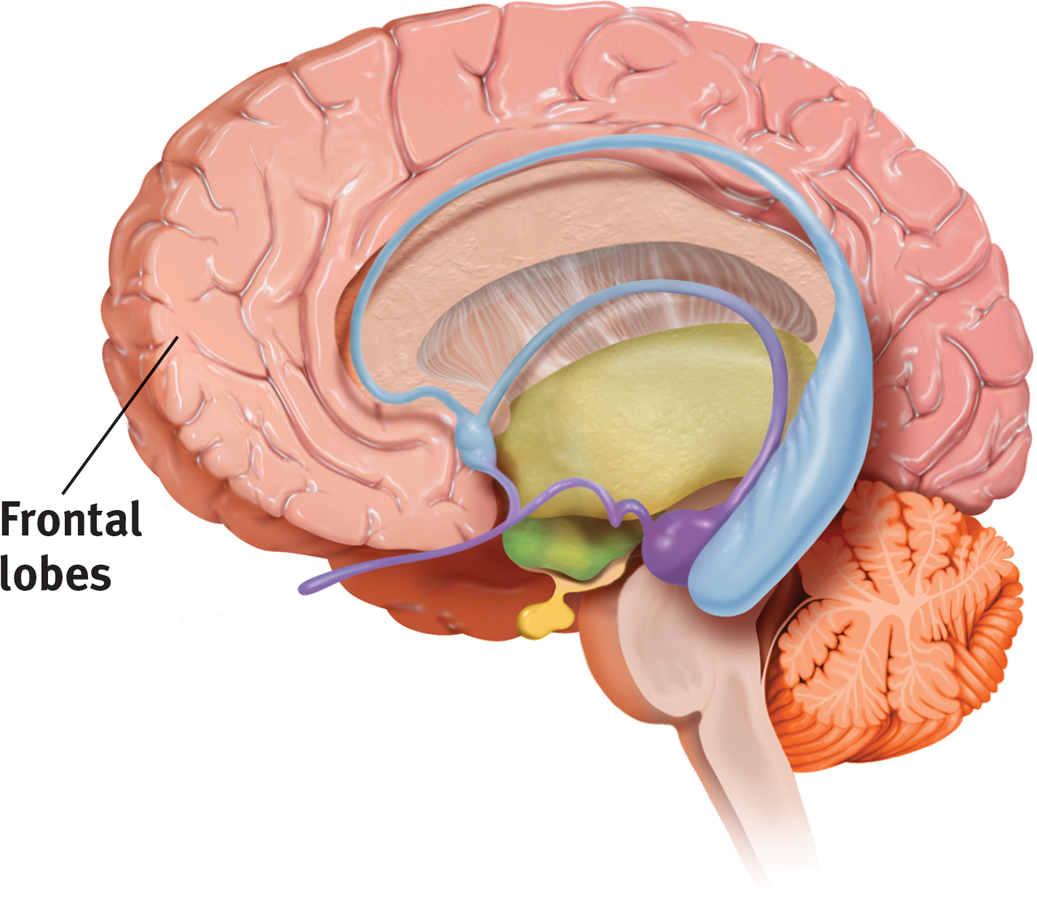

Genetic influences, often in combination with child abuse, help wire the brain (Dodge, 2009). In people with antisocial criminal tendencies, the emotion-

Figure 15.13

Figure 15.13Murderous minds Researchers have found reduced activation in a murderer’s frontal lobes. This brain area (shown in a left-

Does a full Moon trigger “madness” in some people? James Rotton and I. W. Kelly (1985) examined data from 37 studies that related lunar phase to crime, homicides, crisis calls, and mental hospital admissions. Their conclusion: There is virtually no evidence of “Moon madness.” Nor does lunar phase correlate with suicides, assaults, emergency room visits, or traffic disasters (Martin et al., 1992; Raison et al., 1999).

A biologically based fearlessness, as well as early environment, helps explain the reunion of long-

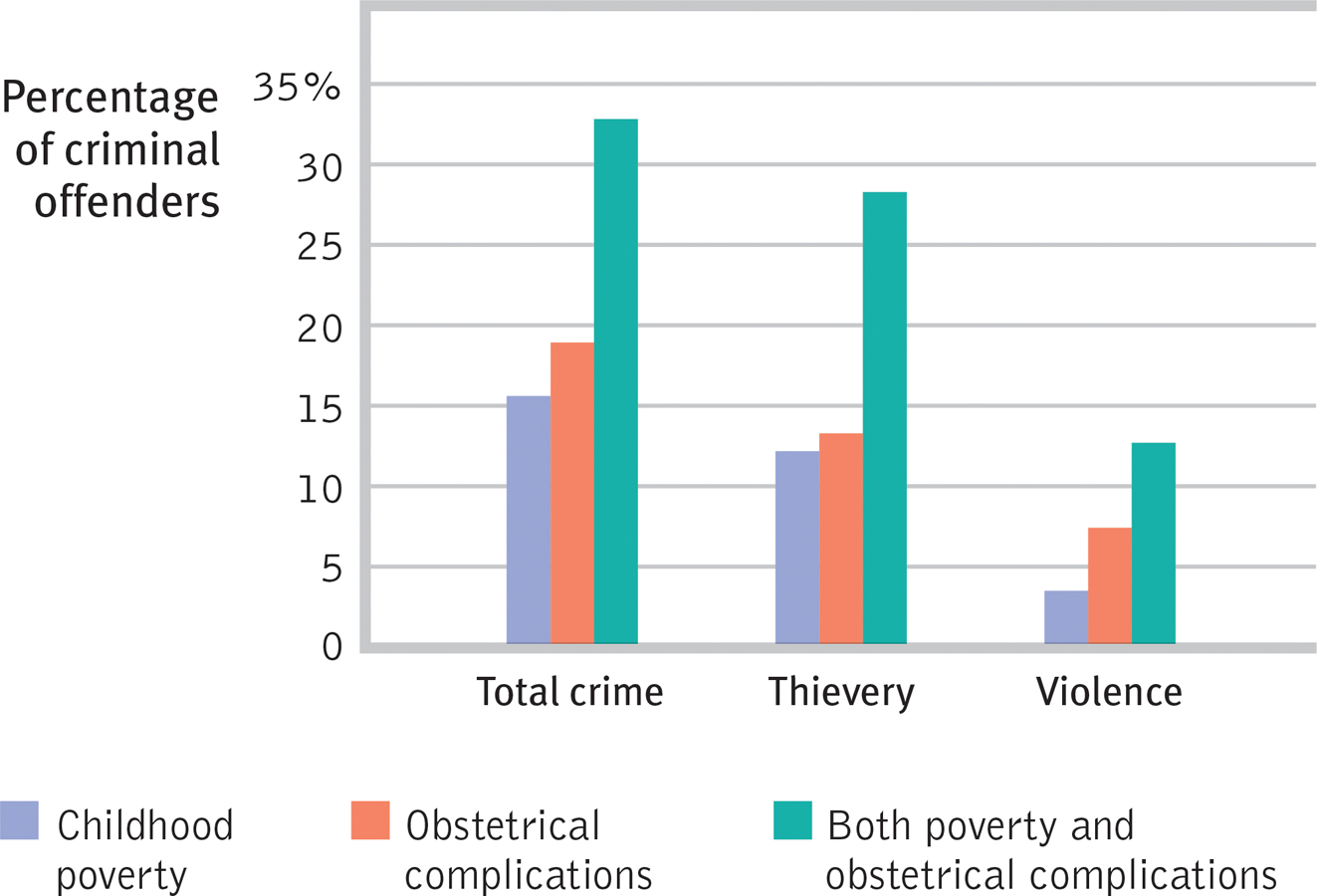

Genetics alone do not tell the whole story of antisocial crime, however. In another Raine-

Figure 15.14

Figure 15.14Biopsychosocial roots of crime Danish male babies whose backgrounds were marked both by obstetrical complications and social stresses associated with poverty were twice as likely to be criminal offenders by ages 20 to 22 as those in either the biological or social risk groups. (Data from Raine et al., 1996.)

651

With antisocial behavior, as with so much else, nature and nurture interact and the biopsychosocial perspective helps us understand the whole story. To explore the neural basis of antisocial personality disorder, neuroscientists are trying to identify brain activity differences in criminals who display symptoms of this disorder. Shown emotionally evocative photographs, such as a man holding a knife to a woman’s throat, criminals with antisocial personality disorder display blunted heart rate and perspiration responses, and less activity in brain areas that typically respond to emotional stimuli (Harenski et al., 2010; Kiehl & Buckholtz, 2010). They also have a larger and hyper-

Question

JIwZtqf61CxhW77M/+aAk9DmsSDyJS8qDm99teqqe4O3JMhS2haqWrgeTaCBzgcvlsjY2UwHWCaNdC3ZZZ1Kj+iQjr81VlmrVrzW8lEMlfEp3dB8pBTNqJDhGchUlElUrcHHEd0Q8ttudtvGzubm91KOjtvBYCUXQRn7CIZWJgc4+1SZb+wXGWhcmTfhjNRklgydhXtxuqxPU4/JXVQGUiJ3YtGA3tbQwM88CGJ7GRvvb2hVXjBiFNMz9sOK2vfWA8SMQQV6bpcaOFm03jL+FLw8TtTz3tpK/t0O8V1vrBJB7b5wAA08PMmsxGMe7GiSnN5ieXHUf9WpCmVqRETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do biological and psychological factors contribute to antisocial personality disorder?

Twin and adoption studies show that biological relatives of people with this disorder are at increased risk for antisocial behavior. Negative environmental factors, such as poverty or childhood abuse, may channel genetic traits such as fearlessness in more dangerous directions—

Eating Disorders

15-

Our bodies are naturally disposed to maintain a steady weight, including stored energy reserves for times when food becomes unavailable. But sometimes psychological influences overwhelm biological wisdom. This becomes painfully clear in three eating disorders.

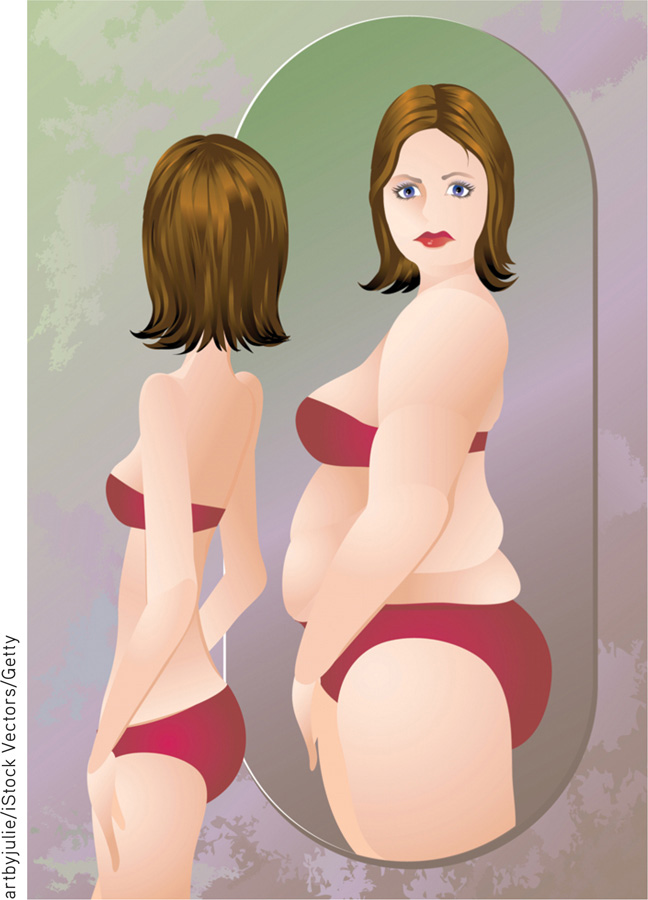

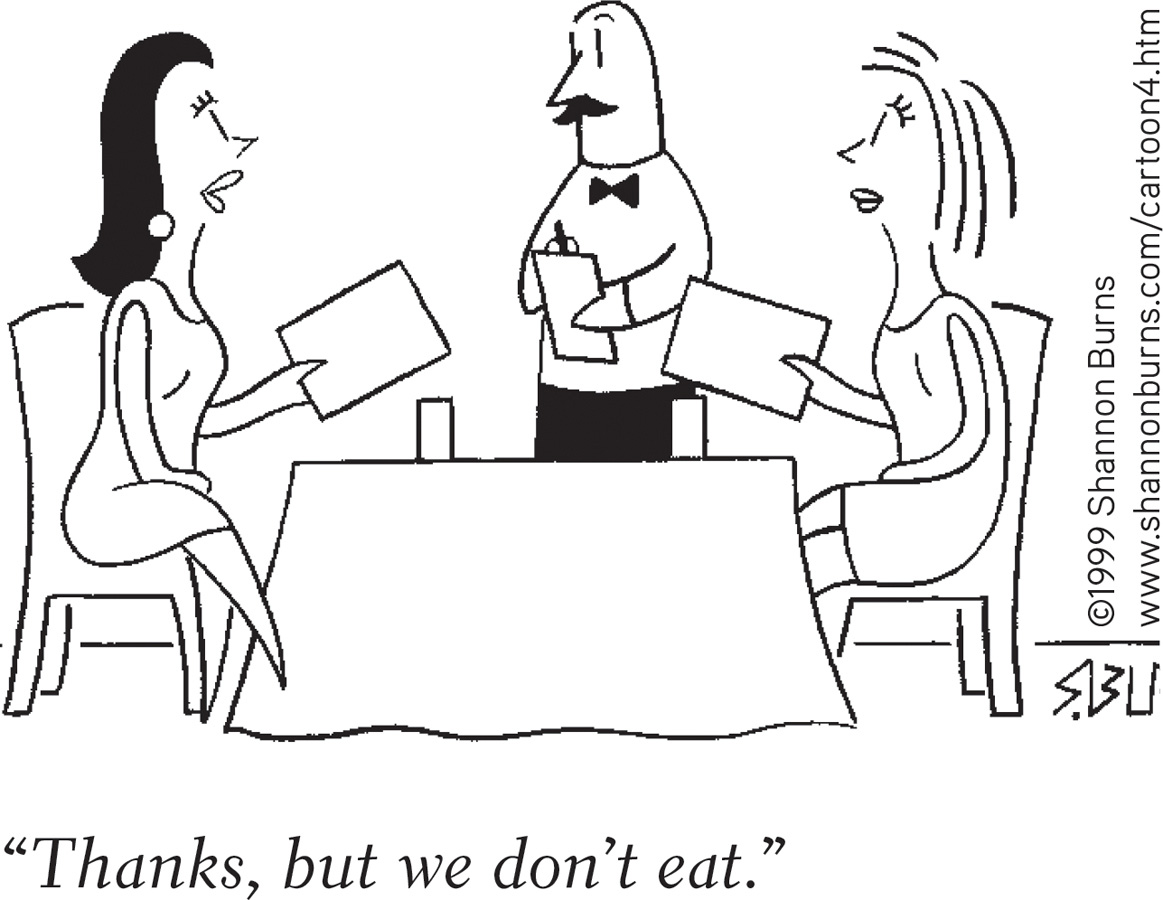

- Anorexia nervosa typically begins as a weight-

loss diet. People with anorexia— usually adolescents and 9 out of 10 times females— drop significantly below normal weight. Yet they feel fat, fear being fat, remain obsessed with losing weight, and sometimes exercise excessively. About half of those with anorexia display a binge- purge- depression cycle. - Bulimia nervosa may also be triggered by a weight-

loss diet, broken by gorging on forbidden foods. Binge- purge eaters— mostly women in their late teens or early twenties— eat in spurts, sometimes influenced by negative emotion or by friends who are bingeing (Crandall, 1988; Haedt- Matt & Keel, 2011). In a cycle of repeating episodes, overeating is followed by compensatory purging (through vomiting or laxative use), fasting, or excessive exercise (Wonderlich et al., 2007). Preoccupied with food (craving sweet and high- fat foods), and fearful of becoming overweight, binge- purge eaters experience bouts of depression, guilt, and anxiety during and following binges (Hinz & Williamson, 1987; Johnson et al., 2002). Unlike anorexia, bulimia is marked by weight fluctuations within or above normal ranges, making the condition easy to hide.  A too-

A too-fat body image underlies anorexia. - Those with binge-

eating disorder engage in significant bouts of overeating, followed by remorse. But they do not purge, fast, or exercise excessively and thus may be overweight.

anorexia nervosa an eating disorder in which a person (usually an adolescent female) maintains a starvation diet despite being significantly underweight; sometimes accompanied by excessive exercise.

bulimia nervosa an eating disorder in which a person alternates binge eating (usually of high-

binge-

652

A U.S. National Institute of Mental Health-

Understanding Eating Disorders

Eating disorders do not provide (as some have speculated) a telltale sign of childhood sexual abuse (Smolak & Murnen, 2002; Stice, 2002). The family environment may provide a fertile ground for the growth of eating disorders in other ways, however.

- Mothers of girls with eating disorders tend to focus on their own weight and on their daughters’ weight and appearance (Pike & Rodin, 1991).

- Families of those with bulimia tend to have a higher-

than- usual incidence of childhood obesity and negative self- evaluation (Jacobi et al., 2004). - Families of those with anorexia tend to be competitive, high-

achieving, and protective (Berg et al., 2014; Pate et al., 1992; Yates, 1989, 1990).

Those with eating disorders often have low self-

Heredity also matters. Identical twins share these disorders more often than fraternal twins do (Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2009; Root et al., 2010). Scientists are now searching for culprit genes, which may influence the body’s available serotonin and estrogen (Klump & Culbert, 2007). In one analysis of 15 studies, having a gene that reduced available serotonin added 30 percent to a person’s risk of anorexia or bulimia (Calati et al., 2011).

But these disorders also have cultural and gender components. Ideal shapes vary across culture and time. In impoverished areas of the world, including much of Africa—

“Why do women have such low self-

Dave Barry, 1999

Those most vulnerable to eating disorders are also those (usually women or gay men) who most idealize thinness and have the greatest body dissatisfaction (Feldman & Meyer, 2010; Kane, 2010; Stice et al., 2010). Should it surprise us, then, that when women view real and doctored images of unnaturally thin models and celebrities, they often feel ashamed, depressed, and dissatisfied with their own bodies—

653

There is, however, more to body dissatisfaction and anorexia than media effects (Ferguson et al., 2011). Peer influences, such as teasing, also matter. So does affluence, increased marriage age, and especially, competition for available mates.

Nevertheless, the sickness of today’s eating disorders stems in part from today’s weight-

If cultural learning contributes to eating behavior, then might prevention programs increase acceptance of one’s body? Reviews of prevention studies answer Yes. They seem especially effective if the programs are interactive and focused on girls over age 15 (Beintner et al., 2012; Stice et al., 2007; Vocks et al., 2010).

***

A growing number of people, especially teenagers and young adults are being diagnosed with psychological disorders. Although mindful of their pain, we can also be encouraged by their successes. Many live satisfying lives. Some pursue brilliant careers, as did 18 U.S. presidents, including the periodically depressed Abraham Lincoln, according to one psychiatric analysis of their biographies (Davidson et al., 2006). The bewilderment, fear, and sorrow caused by psychological disorders are real. But, as this text’s discussion of therapy shows, hope, too, is real.

Question

4ObW1lQXaYMgFn6pSjV+5KFyPtT2jbrim6oZtsF9wLBlu6USp4lOyTyDeVgP7gO+WWy2Hne8aIrJS36dtIyGFA9stgnn81uTZcxen8U0wOhdK9roQCBR3kVGMqCjWC6R47nRKEkHUbdjrfdnSmot7frqYOu6Y4/olRNbfguIjSir5EZXveyU/dYxKzAfJ608nQrGHrS3+KoRlKfaS92qQ6QCzY/XYtYzUPHLDRnlHpiAfA6iblnvfbMGI4JeUmYKu1PWIgaVF1ZAcqt9DATH5eTskU0=RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- People with ______________ (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) continue to want to lose weight even when they are underweight. Those with ______________ (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) tend to have weight that fluctuates within or above normal ranges.

anorexia nervosa; bulimia nervosa

654