16.3 Biomedical Therapies and Preventing Psychological Disorders

Psychotherapy is one way to treat psychological disorders. The other is biomedical therapy—physically changing the brain’s functioning by altering its chemistry with drugs; affecting its circuitry with electroconvulsive shock, magnetic impulses, or psychosurgery; or influencing its responses with changes in lifestyle. By far the most widely used biomedical treatments today are the drug therapies. Primary care providers prescribe most drugs for anxiety and depression, followed by psychiatrists and, in some states, psychologists.

682

Drug Therapies

psychopharmacology the study of the effects of drugs on mind and behavior.

16-

Since the 1950s, discoveries in psychopharmacology (the study of drug effects on mind and behavior) have revolutionized the treatment of people with severe disorders, liberating hundreds of thousands from hospital confinement. Thanks to drug therapy, along with efforts to replace hospitalization with community mental health programs, today’s resident population of mental hospitals is a small fraction of what it was a half-

antipsychotic drugs drugs used to treat schizophrenia and other forms of severe thought disorder.

Almost any new treatment, including drug therapy, is greeted by an initial wave of enthusiasm as many people apparently improve. But that enthusiasm often diminishes after researchers subtract the rates of (1) normal recovery among untreated persons and (2) recovery due to the placebo effect, which arises from the positive expectations of patients and mental health workers alike. Even mere exposure to advertising about a drug’s supposed effectiveness can increase its effect (Kamenica et al., 2013). So, to evaluate the effectiveness of any new drug, researchers give half the patients the drug, and the other half a similar-

Antipsychotic Drugs

The revolution in drug therapy for psychological disorders began with the accidental discovery that certain drugs, used for other medical purposes, calmed patients with psychoses (disorders in which hallucinations or delusions indicate some loss of contact with reality). These first-

The molecules of most conventional antipsychotic drugs are similar enough to molecules of the neurotransmitter dopamine to occupy its receptor sites and block its activity. This finding reinforces the idea that an overactive dopamine system contributes to schizophrenia.

Perhaps you can guess an occasional side effect of l-dopa, a drug that raises dopamine levels for Parkinson’s patients: hallucinations.

Antipsychotics also have powerful side effects. Some produce sluggishness, tremors, and twitches similar to those of Parkinson’s disease (Kaplan & Saddock, 1989). Long-

antianxiety drugs drugs used to control anxiety and agitation.

Antipsychotics, combined with life-

Antianxiety Drugs

Like alcohol, antianxiety drugs, such as Xanax or Ativan, depress central nervous system activity (and so should not be used in combination with alcohol). Antianxiety drugs are often successfully used in combination with psychological therapy. One antianxiety drug, the antibiotic d-cycloserine, facilitates the extinction of learned fears in combination with behavioral treatments. Experiments indicate that the drug enhances the benefits of exposure therapy and helps relieve the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-

683

A criticism sometimes made of the behavior therapies—

Over the dozen years at the end of the twentieth century, the rate of outpatient treatment for anxiety disorders, obsessive-

antidepressant drugs drugs used to treat depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-

Antidepressant Drugs

The antidepressants were named for their ability to lift people up from a state of depression, and this was their main use until recently. The label is a bit of a misnomer now that these drugs are increasingly being used to successfully treat anxiety disorders, obsessive-

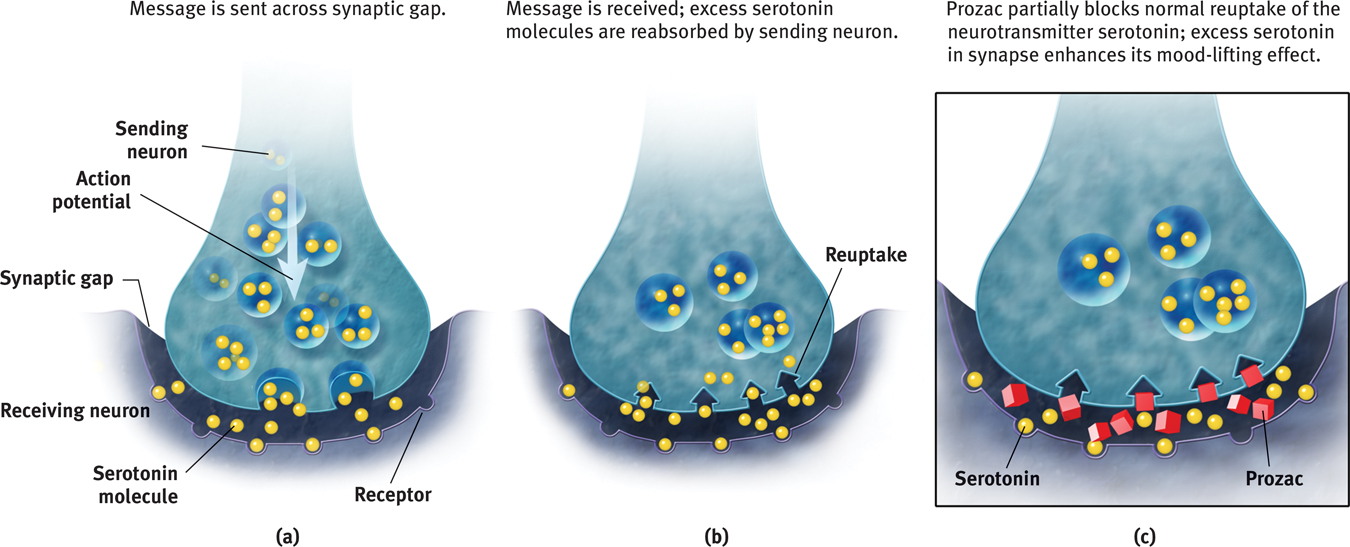

Figure 16.5

Figure 16.5Biology of antidepressants Shown here is the action of Prozac, which partially blocks the reuptake of serotonin.

684

Be advised: Patients with depression who begin taking antidepressants do not wake up the next day singing, “It’s a beautiful day!” Although the drugs begin to influence neurotransmission within hours, their full psychological effect often requires four weeks (and may involve a side effect of diminished sexual desire). One possible reason for the delay is that increased serotonin promotes new synapses plus neurogenesis—the birth of new brain cells—

Antidepressant drugs are not the only way to give the body a lift. Aerobic exercise, which calms people who feel anxious and energizes those who feel depressed, does about as much good for most people with mild to moderate depression, and has additional positive side effects. Cognitive therapy, by helping people reverse their habitual negative thinking style, can boost the drug-

“No twisted thought without a twisted molecule.”

Attributed to psychologist Ralph Gerard

Researchers generally agree that people with depression often improve after a month on antidepressants. But after allowing for natural recovery and the placebo effect, how big is the drug effect? Not big, report Irving Kirsch and his colleagues (1998, 2002, 2010, 2014). Their analyses of double-

HOW WOULD YOU KNOW?To better understand how clinical researchers have explored these questions, complete LaunchPad’s How Would You Know How Well Antidepressants Work?

HOW WOULD YOU KNOW?To better understand how clinical researchers have explored these questions, complete LaunchPad’s How Would You Know How Well Antidepressants Work?

Mood-

In addition to antipsychotic, antianxiety, and antidepressant drugs, psychiatrists have mood-

685

Lithium prevents my seductive but disastrous highs, diminishes my depressions, clears out the wool and webbing from my disordered thinking, slows me down, gentles me out, keeps me from ruining my career and relationships, keeps me out of a hospital, alive, and makes psychotherapy possible.

Lithium reduces bipolar patients’ risk of suicide—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do researchers evaluate the effectiveness of particular drug therapies?

Researchers assign people to treatment and no-

- The drugs given most often to treat depression are called ______________. Schizophrenia is often treated with ______________ drugs.

antidepressants; antipsychotic

Brain Stimulation

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) a biomedical therapy for severely depressed patients in which a brief electric current is sent through the brain of an anesthetized patient.

16-

Electroconvulsive Therapy

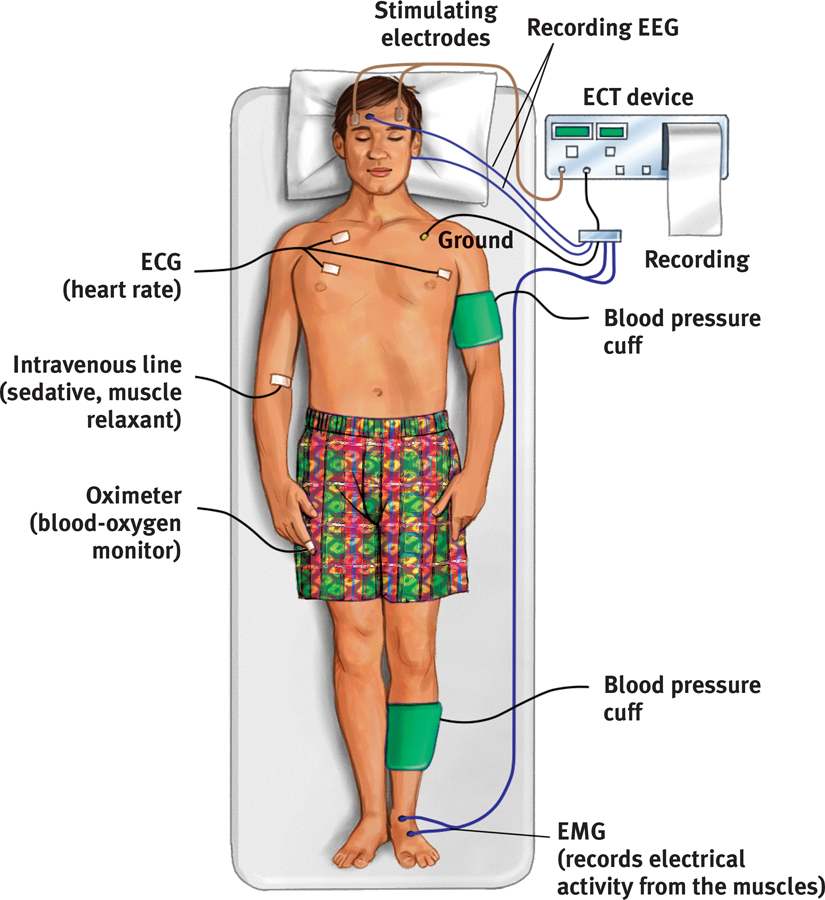

A more controversial brain manipulation occurs through shock treatment, or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). When ECT was first introduced in 1938, the wide-

Figure 16.6

Figure 16.6Electroconvulsive therapy Although controversial, ECT is often an effective treatment for depression that does not respond to drug therapy. (“Electroconvulsive” is no longer accurate, because patients are now given a drug that prevents bodily convulsions.)

How does ECT alleviate severe depression? After more than 70 years, no one knows for sure. One recipient likened ECT to the smallpox vaccine, which was saving lives before we knew how it worked. Others think of it as rebooting their cerebral computer. But what makes it therapeutic? Perhaps the shock-

686

The medical use of electricity is an ancient practice. Physicians treated the Roman Emperor Claudius (10 b.c.e.–54 c.e.) for headaches by pressing electric eels to his temples.

ECT is now administered with briefer pulses, sometimes only to the brain’s right side and with less memory disruption (HMHL, 2007). Yet no matter how impressive the results, the idea of electrically shocking people still strikes many as barbaric, especially given our ignorance about why ECT works. Moreover, about 4 in 10 ECT-

“I used to … be unable to shake the dread even when I was feeling good, because I knew the bad feelings would return. ECT has wiped away that foreboding. It has given me a sense of control, of hope.”

Kitty Dukakis (2006)

repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) the application of repeated pulses of magnetic energy to the brain; used to stimulate or suppress brain activity.

Alternative Neurostimulation Therapies

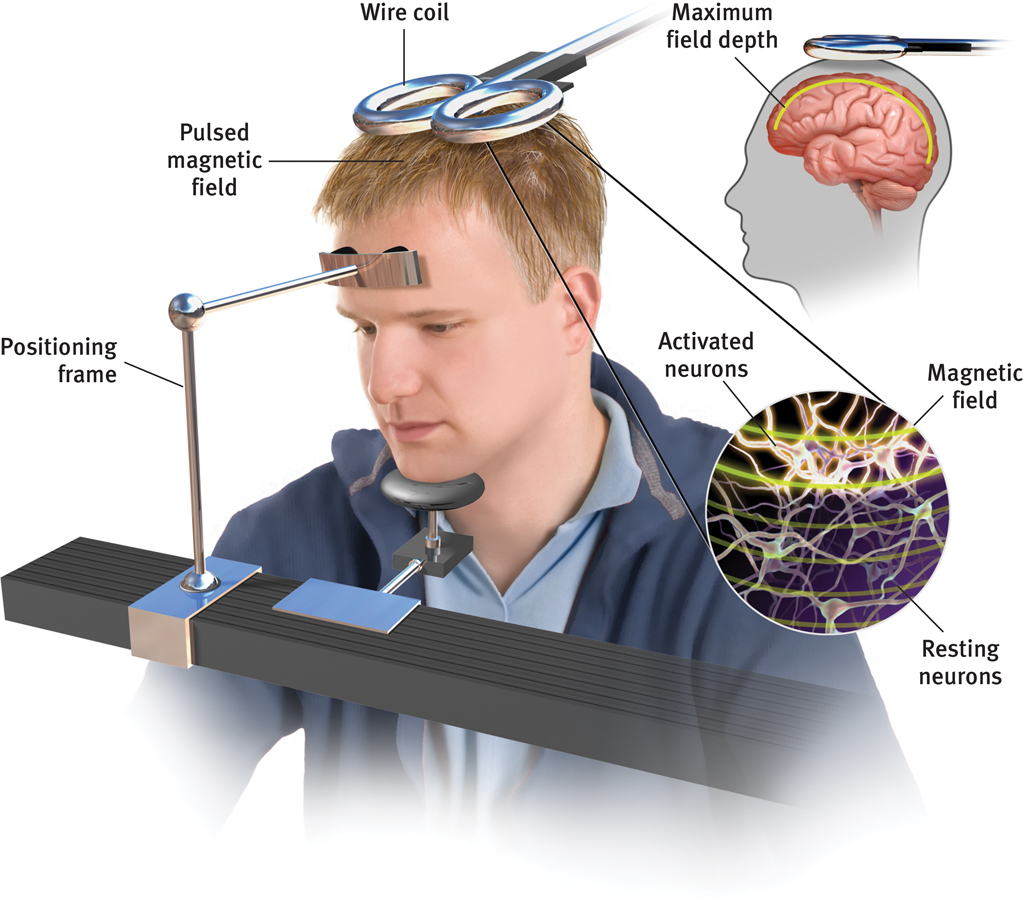

Two other neural stimulation techniques—

Magnetic Stimulation Depressed moods sometimes improve when repeated pulses surge through a magnetic coil held close to a person’s skull (FIGURE 16.7). The painless procedure—

Figure 16.7

Figure 16.7Magnets for the mind Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) sends a painless magnetic field through the skull to the surface of the cortex. Pulses can be used to alter activity in various cortical areas.

A meta-

Seven initial studies have found rTMS to be a “promising treatment,” with results comparable to antidepressants (Berlim et al., 2013). How it works is unclear. One possible explanation is that the stimulation energizes the brain’s left frontal lobe (Helmuth, 2001). Repeated stimulation may cause nerve cells to form new functioning circuits through the process of long-

687

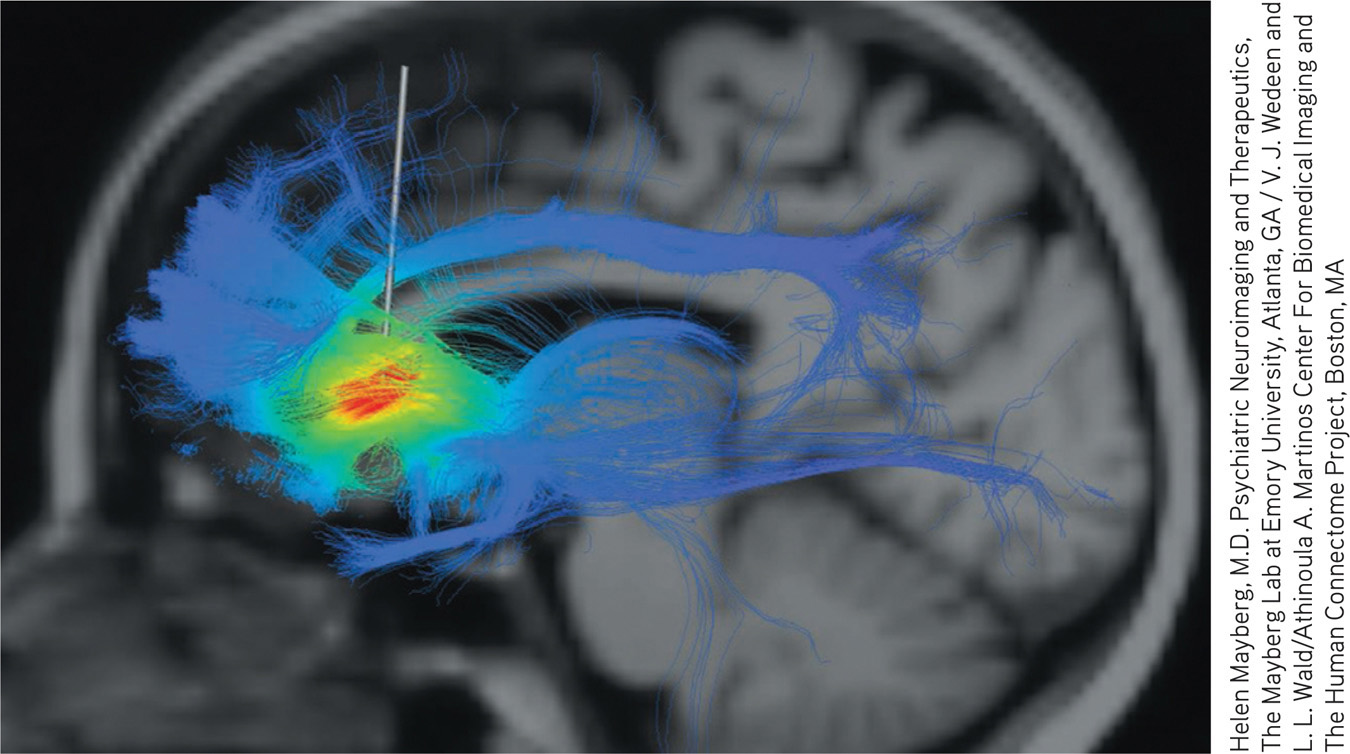

Deep-

Question

VFrnlf0BwGm/tvB242bHU8KlKi0KSN7qEEp2UF8k+TF3/yktZaoyV/omyQfdg7SuEKfNWCCuQIL8ZZHw8xD1ez8VKw1w7A16zvM9YZrQ8ElefJGNPy1tbibZlvOYZ8N8zaPBOFWQ3VTWwT8LVeHn3cVJOrTAwu1Kn2sr+IOZA8z0CY6Do36zAyqYL5BwtaGH1/qNtZTkruG1PKQAoM3baFJWHg456vBB7TbZ1MOhLPQxdBiSYKuloUyzhFOjsRhvumVzJ1egX6T768oPY6LTiXWDE3FGP+EdRUKZpcr/AVjC3X1abKc6eLXveHBxfjR+QSFhCGOs0TEawL+nY575Gc8g0dGBEC5TOlk0X+MbzoNmbGPRRETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Severe depression that has not responded to other therapy may be treated with ______________ ______________, which can cause brain seizures and memory loss. More moderate neural stimulation techniques designed to help alleviate depression include ______________ ______________ magnetic stimulation, and ______________ - ______________ stimulation.

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); repetitive transcranial; deep-

Psychosurgery

psychosurgery surgery that removes or destroys brain tissue in an effort to change behavior.

lobotomy a psychosurgical procedure once used to calm uncontrollably emotional or violent patients. The procedure cut the nerves connecting the frontal lobes to the emotion-

Because its effects are irreversible, psychosurgery—surgery that removes or destroys brain tissue—

Although the intention was simply to disconnect emotion from thought, a lobotomy’s effect was often more drastic: It usually decreased the person’s misery or tension, but also produced a permanently lethargic, immature, uncreative person. During the 1950s, after some 35,000 people had been lobotomized in the United States alone, calming drugs became available and psychosurgery became scorned, as in the saying sometimes attributed to W. C. Fields that “I’d rather have a bottle in front of me than a frontal lobotomy.”

688

Today, lobotomies are history. But more precise, microscale psychosurgery is sometimes used in extreme cases. For example, if a patient suffers uncontrollable seizures, surgeons can deactivate the specific nerve clusters that cause or transmit the convulsions. MRI-

Therapeutic Lifestyle Change

16-

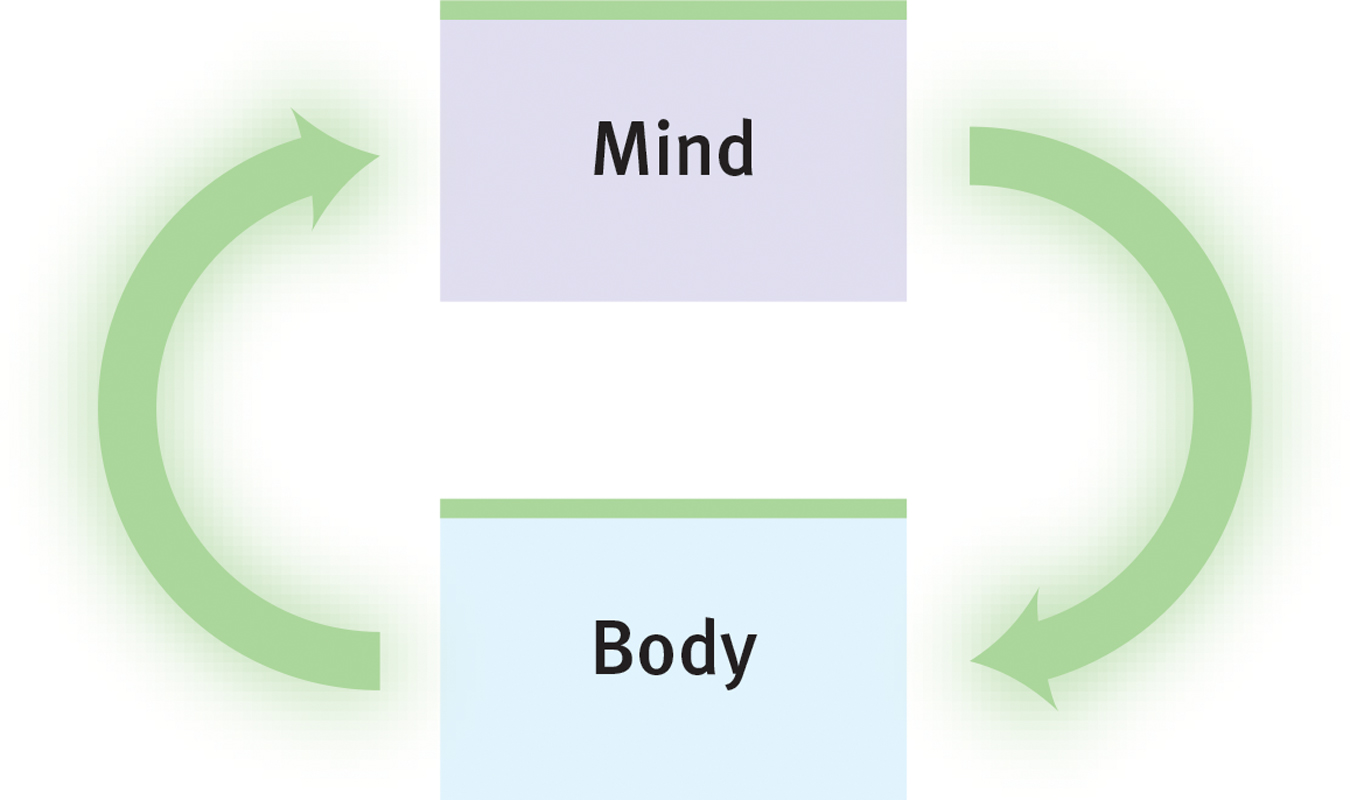

The effectiveness of the biomedical therapies reminds us of a fundamental lesson: We find it convenient to talk of separate psychological and biological influences, but everything psychological is also biological (FIGURE 16.8). Every thought and feeling depends on the functioning brain. Every creative idea, every moment of joy or anger, every period of depression emerges from the electrochemical activity of the living brain. The influence is two-

Figure 16.8

Figure 16.8Mind-

Anxiety disorders, obsessive-

That lesson is being applied by Stephen Ilardi (2009) in training seminars promoting therapeutic lifestyle change. Human brains and bodies were designed for physical activity and social engagement, he notes. Our ancestors hunted, gathered, and built in groups. Indeed, those whose way of life entails strenuous physical activity, strong community ties, sunlight exposure, and plenty of sleep (think of foraging bands in Papua New Guinea, or Amish farming communities in North America) rarely experience depression. For both children and adults, outdoor activity in natural environments—

The Ilardi team was also impressed by research showing that regular aerobic exercise rivals the healing power of antidepressant drugs, and that a complete night’s sleep boosts mood and energy. So they invited small groups of people with depression to undergo a 12-

- Aerobic exercise, 30 minutes a day, at least 3 times weekly (increasing fitness and vitality, stimulating endorphins)

- Adequate sleep, with a goal of 7 to 8 hours a night (increasing energy and alertness, boosting immunity)

- Light exposure, at least 30 minutes each morning with a light box (amplifying arousal, influencing hormones)

- Social connection, with less alone time and at least two meaningful social engagements weekly (satisfying the human need to belong)

- Anti-

rumination, by identifying and redirecting negative thoughts (enhancing positive thinking) - Nutritional supplements, including a daily fish oil supplement with omega-

3 fatty acids (supporting healthy brain functioning)

689

In one study of 74 people, 77 percent of those who completed the program experienced relief from depressive symptoms, compared with 19 percent in those assigned to a treatment-

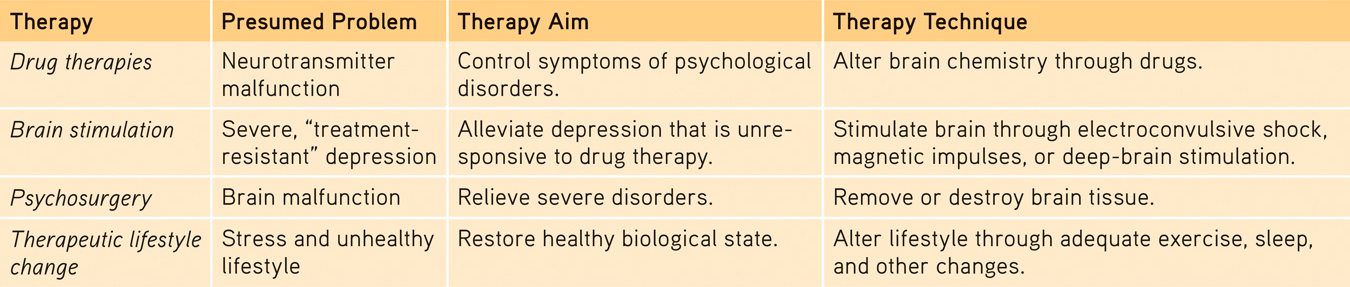

TABLE 16.4 summarizes some aspects of the biomedical therapies we’ve discussed.

Table 16.4

Table 16.4Comparing Biomedical Therapies

Question

eJTThfm5RWxJC0X4uAtIWWYe+o7KCWEyvgzTPrJNR8+Cjrs6f0pzcvuPZONQKFsP9RznAbUUP/FYAzmnY7/KKWVSGRfOSecd7M3hgGEzKOcYRd275OIY1WGCJAmHRdUKyTdEorsgZ4FzPOUuFS0CpqBB4Mr9P4rDI8+49yiKVu9b+DdGc2fqsP9keLowtpveLn1wMubkXToqlGUoq79luu/mFuA8dv8U6vES8o6EkISiGwlWk0U7SRNO1TFML5AJduBc9J/xSh+H5ztHqzTCCFtPS0dDseWlwOV5S44hUAnUpZ3HIBGjaU2D6lU=RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are some examples of lifestyle changes we can make to enhance our mental health?

Exercise regularly, get enough sleep, get more exposure to light (get outside and/or use a light box), nurture important relationships, redirect negative thinking, and eat a diet rich in omega-

Preventing Psychological Disorders and Building Resilience

16-

Psychotherapies and biomedical therapies tend to locate the cause of psychological disorders within the person. We infer that people who act cruelly must be cruel and that people who act “crazy” must be “sick.” We attach labels to such people, thereby distinguishing them from “normal” folks. It follows, then, that we try to treat “abnormal” people by giving them insight into their problems, by changing their thinking, by helping them gain control with drugs.

There is an alternative viewpoint: We could interpret many psychological disorders as understandable responses to a disturbing and stressful society. According to this view, it is not just the person who needs treatment, but also the person’s social context. Better to drain the swamps than swat the mosquitoes. Better to prevent a problem by reforming a sick situation and by developing people’s coping competencies than to wait for and treat problems.

690

Preventive Mental Health

A story about the rescue of a drowning person from a rushing river illustrates this viewpoint: Having successfully administered first aid to the first victim, the rescuer spots another struggling person and pulls her out, too. After a half-

“It is better to prevent than to cure.”

Peruvian folk wisdom

Preventive mental health is upstream work. It seeks to prevent psychological casualties by identifying and alleviating the conditions that cause them. As George Albee (1986; also Yoshikawa et al., 2012) pointed out, there is abundant evidence that poverty, meaningless work, constant criticism, unemployment, racism, and sexism undermine people’s sense of competence, personal control, and self-

We who care about preventing psychological casualties should, Albee contended, support programs that alleviate these demoralizing situations. We eliminated smallpox not by treating the afflicted but by inoculating the unafflicted. We conquered yellow fever by controlling mosquitoes. Preventing psychological problems means empowering those who have learned an attitude of helplessness and changing environments that breed loneliness. It means renewing fragile family ties and boosting parents’ and teachers’ skills at nurturing children’s achievements and resulting self-

“Mental disorders arise from physical ones, and likewise physical disorders arise from mental ones.”

The Mahabharata, 200 b.c.e.

resilience the personal strength that helps most people cope with stress and recover from adversity and even trauma.

Among the upstream prevention workers are community psychologists. Mindful of how people interact with their environment, they focus on creating environments that support psychological health. Through their research and social action, community psychologists aim to empower people and to enhance their competence, health, and well-

Building Resilience

posttraumatic growth positive psychological changes as a result of struggling with extremely challenging circumstances and life crises.

We have seen that lifestyle change can help reverse some of the symptoms of psychological disorders. Might such change also prevent some disorders by building individuals’ resilience—an ability to cope with stress and recover from adversity? Faced with unforeseen trauma, most adults exhibit resilience. This was true of New Yorkers in the aftermath of the September 11 terror attacks, especially those who enjoyed supportive close relationships and who had not recently experienced other stressful events (Bonanno et al., 2007). More than 9 in 10 New Yorkers, although stunned and grief-

691

Struggling with challenging crises can even lead to posttraumatic growth. Many cancer survivors have reported a greater appreciation for life, more meaningful relationships, increased personal strength, changed priorities, and a richer spiritual life (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Americans who tried to make sense of the 9/11 terror attacks experienced less distress (Park et al., 2012). Out of even our worst experiences, some good can come. Through preventive efforts, such as community building and personal growth, fewer of us will fall into the rushing river of psychological disorders.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the difference between preventive mental health and psychological or biomedical therapy?

Psychological and biomedical therapies attempt to relieve people’s suffering from psychological disorders. Preventive mental health attempts to prevent suffering by identifying and eliminating the conditions that cause disorders.

***

If you just finished reading this book, your introduction to psychological science is completed. Our tour of psychological science has taught us much—

With every good wish in your future endeavors,

David G. Myers

www.davidmyers.org

Nathan DeWall

www.NathanDeWall.com

692