1.1 The Need for Psychological Science

1-

Some people suppose that psychology merely documents and dresses in jargon what people already know: “You get paid for using fancy methods to prove what my grandmother knows?” Others place their faith in human intuition: “Buried deep within each and every one of us, there is an instinctive, heart-

Prince Charles has much company, judging from the long list of pop psychology books on “intuitive managing,” “intuitive trading,” and “intuitive healing.” Today’s psychological science does document a vast intuitive mind. As we will see, our thinking, memory, and attitudes operate on two levels—

So, are we smart to listen to the whispers of our inner wisdom, to simply trust “the force within”? Or should we more often be subjecting our intuitive hunches to skeptical scrutiny?

This much seems certain: We often underestimate intuition’s perils. My [DM] geographical intuition tells me that Reno is east of Los Angeles, that Rome is south of New York, that Atlanta is east of Detroit. But I am wrong, wrong, and wrong.

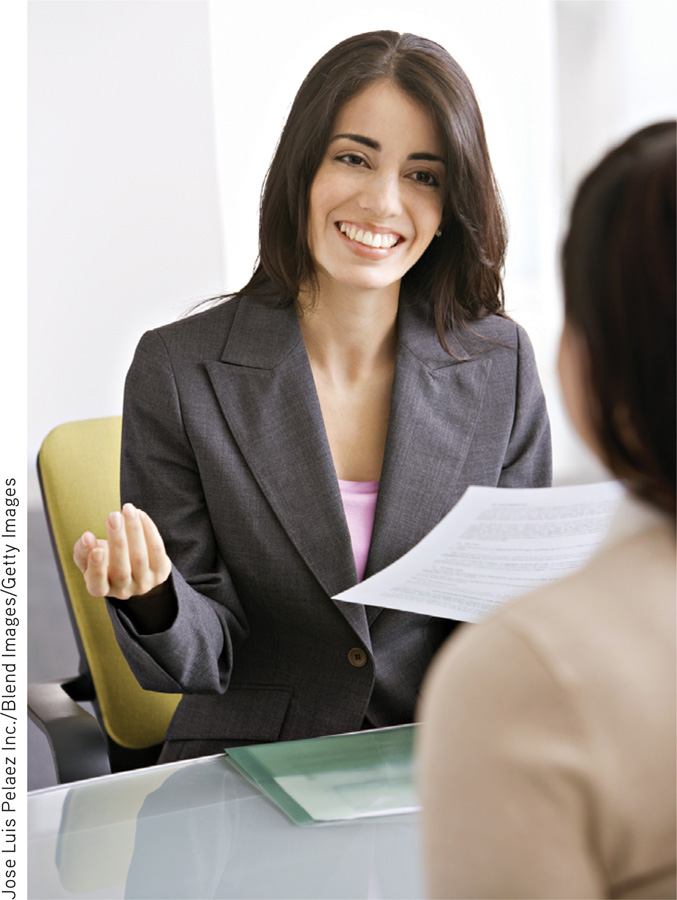

Studies show that people greatly overestimate their lie detection accuracy, their eyewitness recollections, their interviewee assessments, their risk predictions, and their stock-

“Those who trust in their own wits are fools.”

Proverbs 28:26

Indeed, observed novelist Madeleine L’Engle, “The naked intellect is an extraordinarily inaccurate instrument” (1973). Three phenomena—

Did We Know It All Along? Hindsight Bias

“Life is lived forwards, but understood backwards.”

Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, 1813–1855

hindsight bias the tendency to believe, after learning an outcome, that one would have foreseen it. (Also known as the I-

Consider how easy it is to draw the bull’s eye after the arrow strikes. After the stock market drops, people say it was “due for a correction.” After the football game, we credit the coach if a “gutsy play” wins the game, and fault the coach for the “stupid play” if it doesn’t. After a war or an election, its outcome usually seems obvious. Although history may therefore seem like a series of inevitable events, the actual future is seldom foreseen. No one’s diary recorded, “Today the Hundred Years War began.”

“Anything seems commonplace, once explained.”

Dr. Watson to Sherlock Holmes

This hindsight bias (also known as the I-

Tell the second group the opposite, “Psychologists have found that separation strengthens romantic attraction. As the saying goes, “Absence makes the heart grow fonder.” People given this untrue result can also easily imagine it, and most will also see it as unsurprising. When opposite findings both seem like common sense, there is a problem.

Such errors in our recollections and explanations show why we need psychological research. Just asking people how and why they felt or acted as they did can sometimes be misleading—

21

More than 800 scholarly papers have shown hindsight bias in people young and old from across the world (Roese & Vohs, 2012). Nevertheless, Grandma’s intuition is often right. As baseball great Yogi Berra once said, “You can observe a lot by watching.” (We have Berra to thank for other gems, such as “Nobody ever comes here—

Indeed, noted Daniel Gilbert, Brett Pelham, and Douglas Krull (2003), “good ideas in psychology usually have an oddly familiar quality, and the moment we encounter them we feel certain that we once came close to thinking the same thing ourselves and simply failed to write it down.” Good ideas are like good inventions: Once created, they seem obvious. (Why did it take so long for someone to invent suitcases on wheels and Post-

But sometimes Grandma’s intuition, informed by countless casual observations, is wrong. In later chapters, we will see how research has overturned popular ideas—

Overconfidence

Fun anagram solutions from Wordsmith (www.wordsmith.org): Snooze alarms = Alas! No more z’s Dormitory = dirty room

Slot machines = cash lost in ’em

We humans tend to think we know more than we do. Asked how sure we are of our answers to factual questions (Is Boston north or south of Paris?), we tend to be more confident than correct.1 Or consider these three anagrams, which Richard Goranson (1978) asked people to unscramble:

Overconfidence in history:

“We don’t like their sound. Groups of guitars are on their way out.”

Decca Records, in turning down a recording contract with the Beatles in 1962

WREAT → WATER

ETRYN → ENTRY

GRABE → BARGE

22

“Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons.”

Popular Mechanics, 1949

About how many seconds do you think it would have taken you to unscramble each of these? Did hindsight influence you? Knowing the answers tends to make us overconfident. (Surely the solution would take only 10 seconds or so.) In reality, the average problem solver spends 3 minutes, as you also might, given a similar anagram without the solution: OCHSA.2

“They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.”

General John Sedgwick just before being killed during a U.S. Civil War battle, 1864

Are we any better at predicting social behavior? University of Pennsylvania psychologist Philip Tetlock (1998, 2005) collected more than 27,000 expert predictions of world events, such as the future of South Africa or whether Quebec would separate from Canada. His repeated finding: These predictions, which experts made with 80 percent confidence on average, were right less than 40 percent of the time. Nevertheless, even those who erred maintained their confidence by noting they were “almost right.” “The Québécois separatists almost won the secessionist referendum.”

“The telephone may be appropriate for our American cousins, but not here, because we have an adequate supply of messenger boys.”

British expert group evaluating the invention of the telephone

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why, after friends start dating, do we often feel that we knew they were meant to be together?

We often suffer from hindsight bias—

Perceiving Order in Random Events

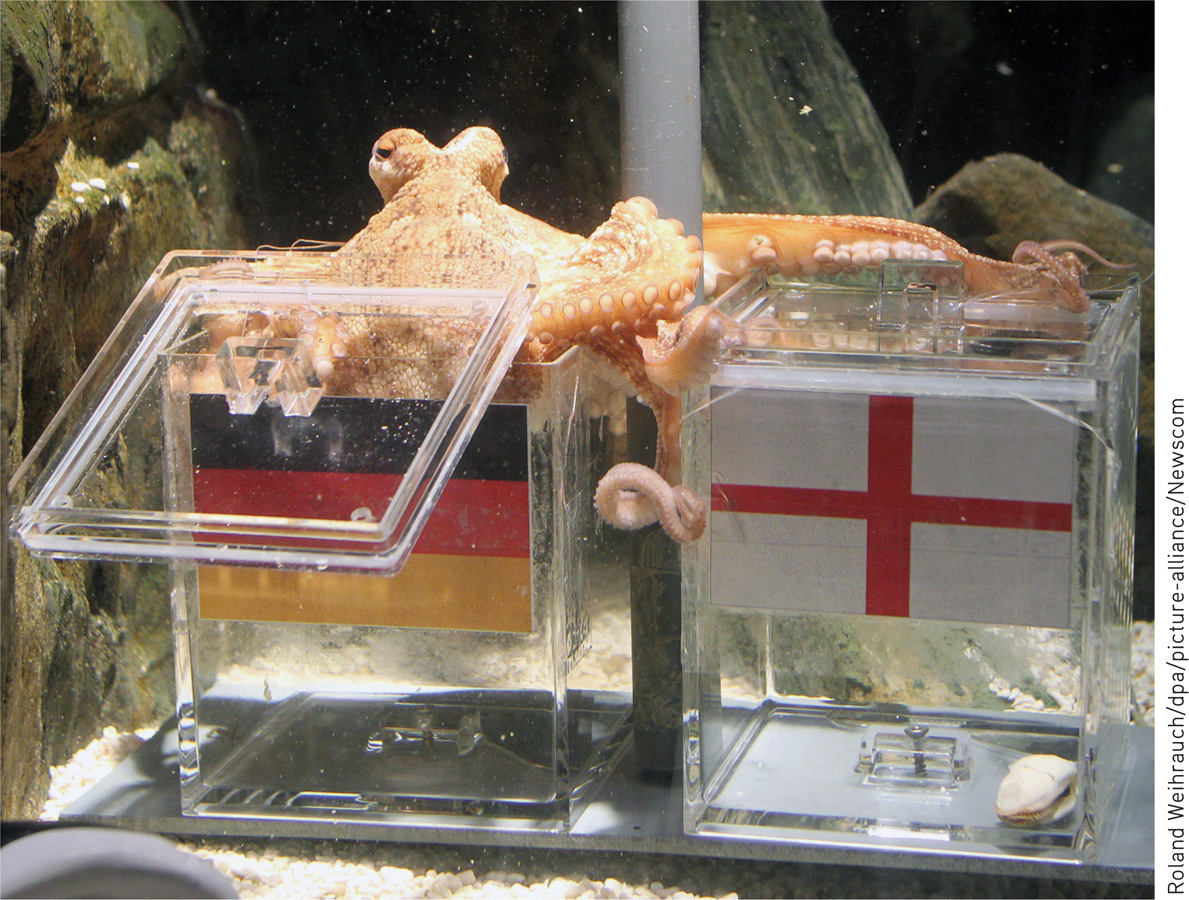

In our natural eagerness to make sense of our world, we perceive patterns. People see a face on the Moon, hear Satanic messages in music, perceive the Virgin Mary’s image on a grilled cheese sandwich. Even in random data, we often find order, because—

However, some happenings, such as winning a lottery twice, seem so extraordinary that we struggle to conceive an ordinary, chance-

Consider how scientific inquiry can help you think smarter about hot streaks in sports with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If There Is a Hot Hand in Basketball?

The point to remember: Hindsight bias, overconfidence, and our tendency to perceive patterns in random events often lead us to overestimate our intuition. But scientific inquiry can help us sift reality from illusion.

is a research-

is a research- HOW WOULD YOU KNOW? activities. For a 1-

HOW WOULD YOU KNOW? activities. For a 1-

Question

qyxhUau3q0m1i+PVflErRiw6DEoLPxXMrB8SbXZ2g17saKcRJQrdMo8MX8mu5oovDdfBgpeeDl1yb0jptOljndLRH51fYGlF7ZXXX7BzxkWd3REINPrbMzeIleTeYEbj/gpzAf5XEQnOhrKpnDZXIYiaAprKCUWbPht1zPplvYt61z1WG0mhwQ7+Qsu/14cpFGSxqZ91HMjKmH+Simo76MYv0AFfco9b0Ejlp3hiJhmB6bhuBi69TD6Do9V93G/wC5/T/+UmzBI=23

The Scientific Attitude: Curious, Skeptical, and Humble

“The really unusual day would be one where nothing unusual happens.”

Statistician Persi Diaconis (2002)

1-

Underlying all science is, first, a hard-

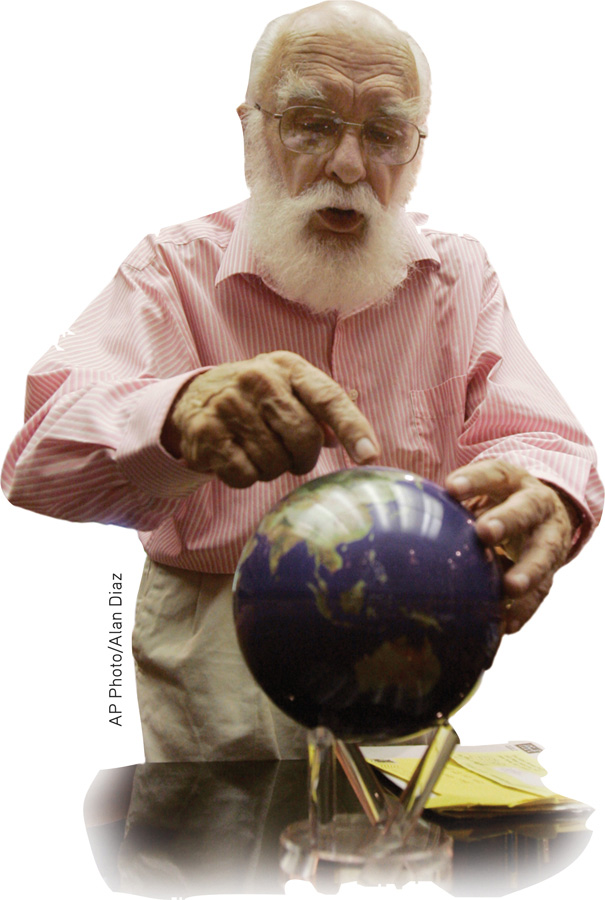

Magician James Randi has used this empirical approach when testing those claiming to see glowing auras around people’s bodies:

Randi:Do you see an aura around my head?

Aura seer:Yes, indeed.

Randi:Can you still see the aura if I put thismagazine in front of my face?

Aura seer:Of course.

Randi:Then if I were to step behind a wallbarely taller than I am, you could determine mylocation from the aura visible above my head, right?

Randi once told me that no aura seer has agreed to take this simple test.

No matter how sensible-

More often, science becomes society’s garbage disposal, sending crazy-

“To believe with certainty,” says a Polish proverb, “we must begin by doubting.” As scientists, psychologists approach the world of behavior with a curious skepticism, persistently asking two questions: What do you mean? How do you know?

When ideas compete, skeptical testing can reveal which ones best match the facts. Do parental behaviors determine children’s sexual orientation? Can astrologers predict your future based on the position of the planets at your birth? Is electroconvulsive therapy (delivering an electric shock to the brain) an effective treatment for severe depression? As we will see, putting such claims to the test has led psychological scientists to answer No to the first two questions and Yes to the third.

Putting a scientific attitude into practice requires not only curiosity and skepticism but also humility—an awareness of our own vulnerability to error and an openness to surprises and new perspectives. In the last analysis, what matters is not my opinion or yours, but the truths nature reveals in response to our questioning. If people or other animals don’t behave as our ideas predict, then so much the worse for our ideas. This humble attitude was expressed in one of psychology’s early mottos: “The rat is always right.”

24

“My deeply held belief is that if a god anything like the traditional sort exists, our curiosity and intelligence are provided by such a god. We would be unappreciative of those gifts … if we suppressed our passion to explore the universe and ourselves.”

Carl Sagan, Broca’s Brain, 1979

Historians of science tell us that these three attitudes—

Of course, scientists, like anyone else, can have big egos and may cling to their preconceptions. Nevertheless, the ideal of curious, skeptical, humble scrutiny of competing ideas unifies psychologists as a community as they check and recheck one another’s findings and conclusions.

Critical Thinking

critical thinking thinking that does not blindly accept arguments and conclusions. Rather, it examines assumptions, appraises the source, discerns hidden values, evaluates evidence, and assesses conclusions.

From a Twitter feed:

“The problem with quotes on the Internet is that you never know if they’re true.”—Abraham Lincoln

The scientific attitude prepares us to think smarter. Smart thinking, called critical thinking, examines assumptions, appraises the source, discerns hidden values, evaluates evidence, and assesses conclusions. Whether reading online commentary or listening to a conversation, critical thinkers ask questions: How do they know that? What is this person’s agenda? Is the conclusion based on anecdote and gut feelings, or on evidence? Does the evidence justify a cause–

“The real purpose of the scientific method is to make sure Nature hasn’t misled you into thinking you know something you don’t actually know.”

Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, 1974

Critical thinking, informed by science, helps clear the colored lenses of our biases. Consider: Does climate change threaten our future, and, if so, is it human-

Has psychology’s critical inquiry been open to surprising findings? The answer, as ensuing chapters illustrate, is plainly Yes. Some examples: Massive losses of brain tissue early in life may have minimal long-

25

And has critical inquiry convincingly debunked popular presumptions? The answer, as ensuing chapters also illustrate, is again Yes. The evidence indicates that sleepwalkers are not acting out their dreams (see Chapter 3). Our past experiences are not all recorded verbatim in our brains; with brain stimulation or hypnosis, one cannot simply replay and relive long-

Psychological science can also identify effective policies. To deter crime, should we invest money in lengthening prison sentences or increase the likelihood of arrest? To help people recover from a trauma, should counselors help them relive it, or not? To increase voting, should we tell people about the low turnout problem, or emphasize that their peers are voting? When put to critical thinking’s test—

Question

T2qg+FN7Glq8vLMtTMSWnj9u+e360b7nlcA9A/ACD8k5VcIxyXyRCNY9uB1FcgJr7o5+vwC3lpCi1HbfcZ6SxAgwLDpAwqXYgfu0AY/kyaAuAujbj1DvA6F0BqH9Ei3TVR/4U/k/okPm27AWF60J4Yo0tQJd+JK/WgW8IWBqi8Q+FeB9ZsxYL/wfRBwsFpWtR8Hgj8FJJheA5D13ENDCf1Y72IQrlAOB6Fu+qBku1R3YUF2I0ofnIfTtSUje5yDNzcGg9XLhaukkA21OGZsX1dKyGBQPHWdoOJxcRCx2U8TllH+DQPlxOxYH2i7Ur+gpqB64ZiqJaqdyoDCncwyXbGQPw5rEfrCo5IWLP5ae/LO5Ndk3qAil7FZsEeuBdZ+P7iv5aa2hzaE=RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- “For a lot of bad ideas, science is society’s garbage disposal.” Describe what this tells us about the scientific attitude and what’s involved in critical thinking.

The scientific attitude combines (1) curiosity about the world around us, (2) skepticism about unproven claims and ideas, and (3) humility about one’s own understanding. Evaluating evidence, assessing conclusions, and examining our own assumptions are essential parts of critical thinking.