4.2 Evolutionary Psychology: Understanding Human Nature

evolutionary psychology the study of the evolution of behavior and the mind, using principles of natural selection.

4-

natural selection the principle that, among the range of inherited trait variations, those contributing to reproduction and survival will most likely be passed on to succeeding generations.

Behavior geneticists explore the genetic and environmental roots of human differences. Evolutionary psychologists instead focus mostly on what makes us so much alike as humans. They use Charles Darwin’s principle of natural selection—“arguably the most momentous idea ever to occur to a human mind,” said Richard Dawkins (2007)—to understand the roots of behavior and mental processes. The idea, simplified, is this:

- Organisms’ varied offspring compete for survival.

- Certain biological and behavioral variations increase organisms’ reproductive and survival chances in their particular environment.

- Offspring that survive are more likely to pass their genes to ensuing generations.

- Thus, over time, population characteristics may change.

To see these principles at work, let’s consider a straightforward example in foxes.

Natural Selection and Adaptation

A fox is a wild and wary animal. If you capture a fox and try to befriend it, be careful. Stick your hand in the cage and, if the timid fox cannot flee, it may snack on your fingers. Russian scientist Dmitry Belyaev wondered how our human ancestors had domesticated dogs from their equally wild wolf forebears. Might he, within a comparatively short stretch of time, accomplish a similar feat by transforming the fearful fox into a friendly fox?

145

To find out, Belyaev set to work with 30 male and 100 female foxes. From their offspring he selected and mated the tamest 5 percent of males and 20 percent of females. (He measured tameness the foxes’ responses to attempts to feed, handle, and stroke them.) Over more than 30 generations of foxes, Belyaev and his successor, Lyud-

mutation a random error in gene replication that leads to a change.

Over time, traits that give an individual or a species a reproductive advantage are selected and will prevail. Animal breeding experiments manipulate genetic selection. Dog breeders have given us sheepdogs that herd, retrievers that retrieve, trackers that track, and pointers that point (Plomin et al., 1997). Psychologists, too, have bred animals to be serene or reactive, quick learners or slow ones.

Does the same process work with naturally occurring selection? Does natural selection explain our human tendencies? Nature has indeed selected advantageous variations from the new gene combinations produced at each human conception plus the mutations (random errors in gene replication) that sometimes result. But the tight genetic leash that predisposes a dog’s retrieving, a cat’s pouncing, or a bird’s nesting is looser on humans. The genes selected during our ancestral history provide more than a long leash; they give us a great capacity to learn and therefore to adapt to life in varied environments, from the tundra to the jungle. Genes and experience together wire the brain. Our adaptive flexibility in responding to different environments contributes to our fitness—our ability to survive and reproduce.

Question

wFzN4IZBQdDaGWdN3GfD/i30hGPLcS79to+1eGLxGF1vpXYB82ivrSn4bYDYH1podtasqYHeHUTHJkftMOEn39KS+BbUR8Mt1jcPI1QWajax3djMRraayBqhVjIz/cVeDnklyIbERQNBCYc8XNCh+AsdBf7VsPEDsRbOqAr8z4CIQ8nk7u3WK3bQ08XTJ9CpCBerbjH4SwoRQm+Il9sNO3imupOd7lhqVR+SPu9b26KlTjtlcdrSA9ZWycbh+YpHRETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How are Belyaev and Trut’s breeding practices similar to, and how do they differ from, the way natural selection normally occurs?

Over multiple generations, Belyaev and Trut selected and bred foxes that exhibited a trait they desired: tameness. This process is similar to naturally occurring selection, but it differs in that natural selection normally favors traits (including those arising from mutations) that contribute to reproduction and survival.

- Would the heritability of aggressiveness be greater in Belyaev and Trut’s foxes, or in a wild population of foxes? variation in aggressiveness.

Heritability of aggressiveness would be greater in the wild population, with its greater genetic variation in aggressiveness.

Evolutionary Success Helps Explain Similarities

Human differences grab our attention. The Guinness World Records entertains us with the height of the tallest-

146

Our Genetic Legacy

Our behavioral and biological similarities arise from our shared human genome, our common genetic profile. No more than 5 percent of the genetic differences among humans arise from population group differences. Some 95 percent of genetic variation exists within populations (Rosenberg et al., 2002). The typical genetic difference between two Icelandic villagers or between two Kenyans is much greater than the average difference between the two groups. Thus, if after a worldwide catastrophe only Icelanders or Kenyans survived, the human species would suffer only “a trivial reduction” in its genetic diversity (Lewontin, 1982).

And how did we develop this shared human genome? At the dawn of human history, our ancestors faced certain questions: Who is my ally, who is my foe? With whom should I mate? What food should I eat? Some individuals answered those questions more successfully than others. For example, women who experienced nausea in the critical first three months of pregnancy were genetically predisposed to avoid certain bitter, strongly flavored, and novel foods. Avoiding such foods has survival value, since they are the very foods most often toxic to prenatal development (Profet, 1992; Schmitt & Pilcher, 2004). Early humans disposed to eat nourishing rather than poisonous foods survived to contribute their genes to later generations. Those who deemed leopards “nice to pet” often did not.

Similarly successful were those whose mating helped them produce and nurture offspring. Over generations, the genes of individuals not so disposed tended to be lost from the human gene pool. As success-

Despite high infant mortality and rampant disease in past millennia, not one of your countless ancestors died childless.

Across our cultural differences, we even share a “universal moral grammar” (Mikhail, 2007). Men and women, young and old, liberal and conservative, living in Sydney or Seoul, all respond negatively when asked, “If a lethal gas is leaking into a vent and is headed toward a room with seven people, is it okay to push someone into the vent—

As inheritors of this prehistoric legacy, we are genetically predisposed to behave in ways that promoted our ancestors’ surviving and reproducing. But in some ways, we are biologically prepared for a world that no longer exists. We love the taste of sweets and fats, nutrients that prepared our physically active ancestors to survive food shortages. But few of us now hunt and gather our food. Too often, we search for sweets and fats in fast-

Those who are troubled by an apparent conflict between scientific and religious accounts of human origins may find it helpful to recall from this text’s Prologue that different perspectives of life can be complementary. For example, the scientific account attempts to tell us when and how; religious creation stories usually aim to tell about an ultimate who and why. As Galileo explained to the Grand Duchess Christina, “The Bible teaches how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go.”

Evolutionary Psychology Today

Darwin’s theory of evolution has become one of biology’s organizing principles. “Virtually no contemporary scientists believe that Darwin was basically wrong,” noted Jared Diamond (2001). Today, Darwin’s theory lives on in the second Darwinian revolution, the application of evolutionary principles to psychology. In concluding On the Origin of Species, Darwin (1859, p. 346) anticipated this, foreseeing “open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation.”

147

Elsewhere in this text, we address questions that intrigue evolutionary psychologists: Why do infants start to fear strangers about the time they become mobile? Why are biological fathers so much less likely than unrelated boyfriends to abuse and murder the children with whom they share a home? Why do so many more people have phobias about spiders, snakes, and heights than about more dangerous threats, such as guns and electricity? And why do we fear air travel so much more than driving?

To see how evolutionary psychologists think and reason, let’s pause to explore their answers to two questions: How are males and females alike? How and why does their sexuality differ?

An Evolutionary Explanation of Human Sexuality

4-

Having faced many similar challenges throughout history, males and females have adapted in similar ways: We eat the same foods, avoid the same predators, and perceive, learn, and remember similarly. It is only in those domains where we have faced differing adaptive challenges—

Male-

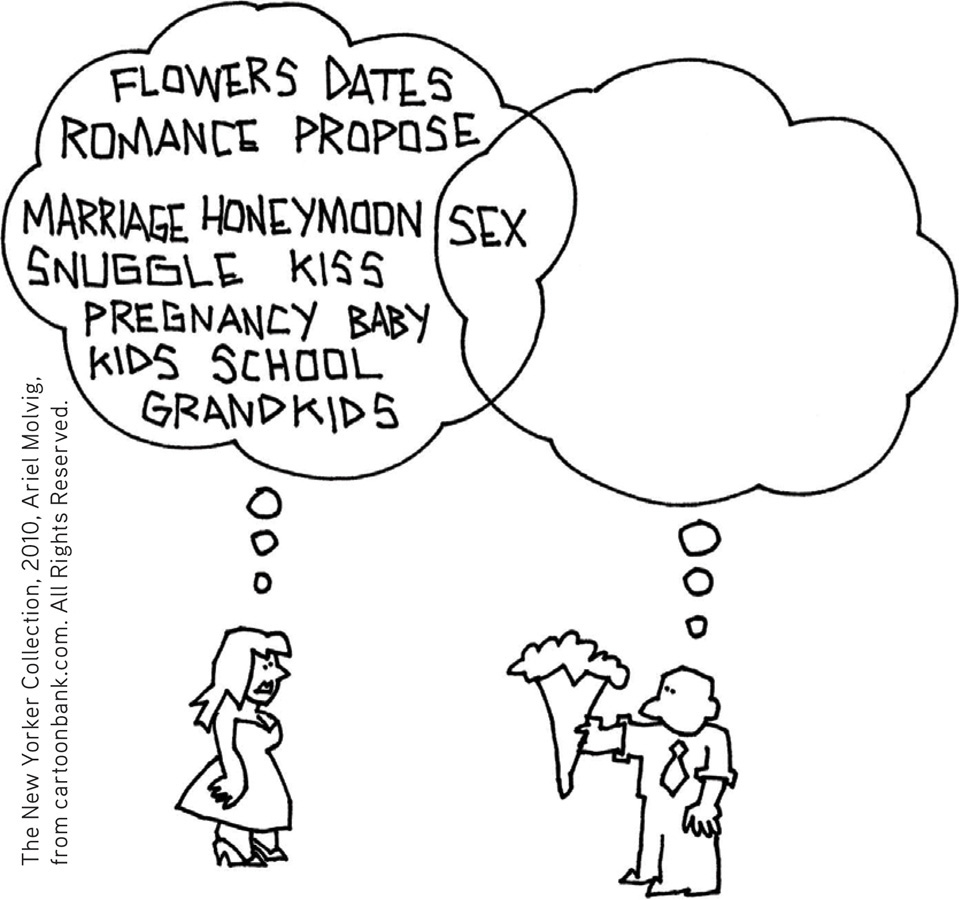

And differ we do. Consider sex drives. Both men and women are sexually motivated, some women more so than many men. Yet, on average, who thinks more about sex? Masturbates more often? Initiates more sex? Views more pornography? The answers worldwide: men, men, men, and men (Baumeister et al., 2001; Lippa, 2009; Petersen & Hyde, 2010). No surprise, then, that in one BBC survey of more than 200,000 people in 53 nations, men everywhere more strongly agreed that “I have a strong sex drive” and “It doesn’t take much to get me sexually excited” (Lippa, 2008).

Indeed, “with few exceptions anywhere in the world,” reported cross-

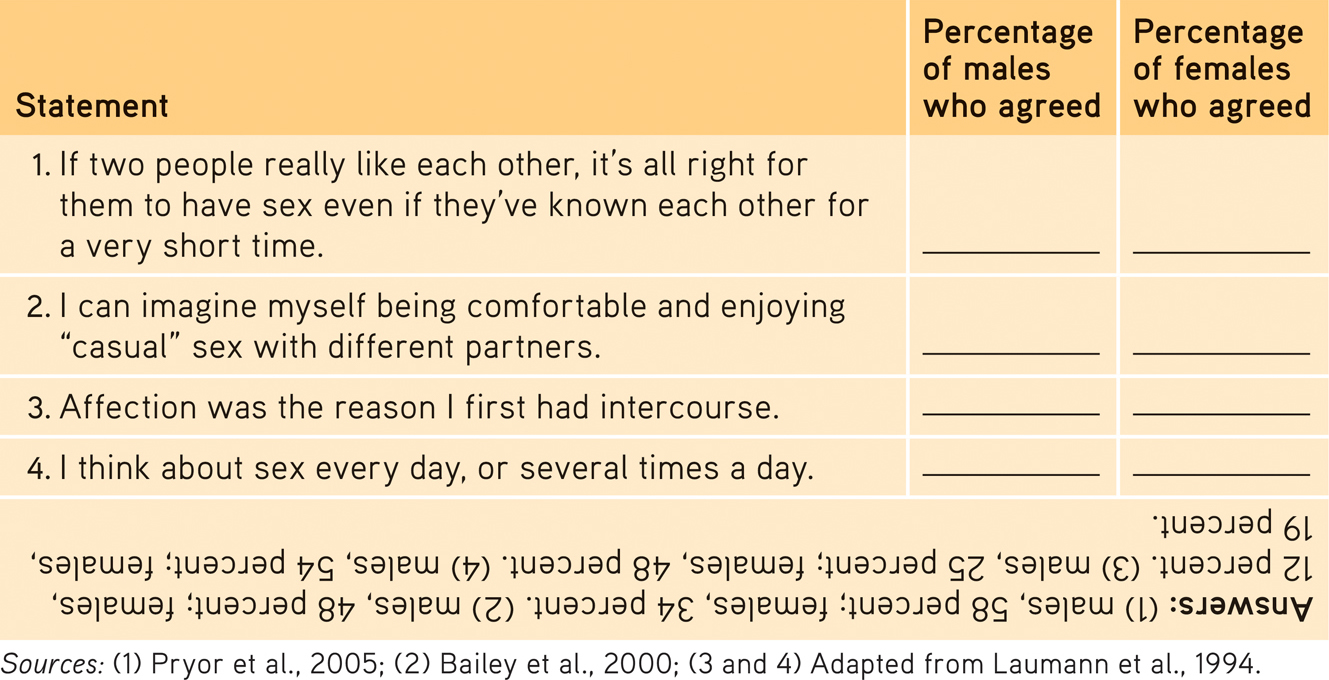

Table 4.1

Table 4.1Predict the Responses

Researchers asked samples of U.S. adults whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements. For each item below, give your best guess about the percentage who agreed with the statement.

Compared with lesbians, gay men (like straight men) have reported more interest in uncommitted sex, more responsiveness to visual sexual stimuli, and more concern with their partner’s physical attractiveness (Bailey et al., 1994; Doyle, 2005; Schmitt, 2007; Sprecher et al., 2013). Gay male couples report having sex more often than do lesbian couples (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007). And in the first year of Vermont’s same-

“It’s not that gay men are oversexed; they are simply men whose male desires bounce off other male desires rather than off female desires.”

Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works, 1997

Webster, G. D., Jonason, P. K., & Schember, T. O. (2009). Hot topics and popular papers in evolutionary psychology: Analyses of title words and citation counts in Evolution and Human Behavior, 1979–2008. Evolutionary Psychology, 7, 348–362.

148

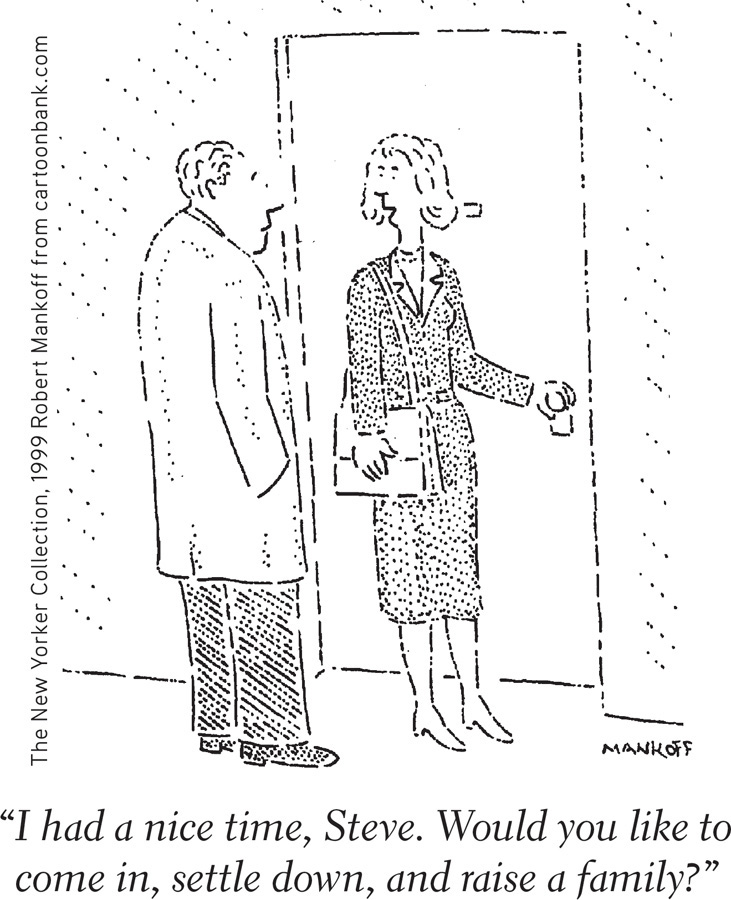

Heterosexual men often misperceive a woman’s friendliness as a sexual come-

To listen to experts discuss evolutionary psychology and sex differences, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Evolutionary Psychology and Sex Differences.

To listen to experts discuss evolutionary psychology and sex differences, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Evolutionary Psychology and Sex Differences.

Natural Selection and Mating Preferences

The principle of natural selection proposes that nature selects traits and appetites that contribute to survival and reproduction. Evolutionary psychologists use this principle to explain how men and women differ more in the bedroom than in the boardroom. Our natural yearnings, they say, are our genes’ way of reproducing themselves. “Humans are living fossils—

Why do women tend to be choosier than men when selecting sexual partners? Women have more at stake. To send her genes into the future, a woman must—

149

The data are in, say evolutionists: Men pair widely; women pair wisely. And what traits do straight men find desirable? Some, such as a woman’s smooth skin and youthful shape, cross place and time, and they convey health and fertility (Buss, 1994). Mating with such women might give a man a better chance of sending his genes into the future. And sure enough, men feel most attracted to women whose waists (thanks to their genes or their surgeons) are roughly a third narrower than their hips—

“She’s beautiful, and therefore to be woo’d.”

William Shakespeare, King Henry IV

There is a principle at work here, say evolutionary psychologists: Nature selects behaviors that increase the likelihood of sending one’s genes into the future. As mobile gene machines, we are designed to prefer whatever worked for our ancestors in their environments. They were genetically predisposed to act in ways that would leave grandchildren. Had they not been, we wouldn’t be here. As carriers of their genetic legacy, we are similarly predisposed.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of evolutionary psychology and mating preferences, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Dating and Mating.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of evolutionary psychology and mating preferences, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Dating and Mating.

Critiquing the Evolutionary Perspective

4-

Most psychologists agree that natural selection prepares us for survival and reproduction. But critics say there is a weakness in the reasoning evolutionary psychologists use to explain our mating preferences. Let’s consider how an evolutionary psychologist might explain the findings in a startling study (Clark & Hatfield, 1989), and how a critic might object.

Participants were approached by a “stranger” of the other sex (someone working for the experimenter). The stranger remarked “I have been noticing you around campus. I find you to be very attractive,” and then asked one of three questions:

- Would you go out with me tonight?

- Would you come over to my apartment tonight?

- Would you go to bed with me tonight?

150

What percentage of men and women do you think agreed to each offer? The evolutionary explanation of sexuality predicts that women will be choosier than men in selecting their sexual partners and will be less willing to hop in bed with a complete stranger. In fact, not a single woman—

social script culturally modeled guide for how to act in various situations.

Or did it? Critics note that evolutionary psychologists start with an effect—

Other critics ask why we should try to explain today’s behavior based on decisions our distant ancestors made thousands of years ago. They believe social learning theory offers a better, more immediate explanation for these results. Perhaps women learn social scripts—their culture’s guide to how people should act in certain situations. By watching and imitating others in their culture, they may learn that sexual encounters with strangers are dangerous, and that men who ask for casual sex will not offer women much sexual pleasure (Conley, 2011). This alternative explanation of the study’s effects proposes that women react to sexual encounters in ways that their modern culture teaches them.

A third criticism focuses on the social consequences of accepting an evolutionary explanation. Are heterosexual men truly hard-

Evolutionary psychologists agree that much of who we are is not hard-

“It is dangerous to show a man too clearly how much he resembles the beast, without at the same time showing him his greatness. It is also dangerous to allow him too clear a vision of his greatness without his baseness. It is even more dangerous to leave him in ignorance of both.”

Blaise Pascal, Pensées, 1659

Evolutionary psychologists also agree with their critics that some traits and behaviors, such as suicide, are hard to explain in terms of natural selection (Barash, 2012; Confer et al., 2010). But they ask us to remember evolutionary psychology’s scientific goal: to explain behaviors and mental traits by offering testable predictions using principles of natural selection. We can, for example, scientifically test hypotheses such as: Do we tend to favor others to the extent that they share our genes or can later return our favors? (The answer is Yes.) They also remind us that studying how we came to be need not dictate how we ought to be. Understanding our tendencies can help us overcome them.

Question

8iD/KSoe0gRkc1BCycZEyPRyspNmkGu7k/7807wwddEWfrbNtYup2el8vYFSSaCVFGJz5XLuG/hLBonpa1lbbTRSrukX79dp7jsokBpqKAW8rrRe1OJoWjcfCEETcEpaojuqGVZ5pviLsx8eEKqfGblZXm/7D1D3lHRbVuTHFFLp7C7ISPKAC5pS37Yes0NiGIFFdATBu0Y4ijDMTbiq4cP/1IJwVk90dH55VtK2s0SPfzRkNThI4rGNn4FtEmMszknhBiwYZaTOqv96C++1Zj2h+WHg9av7RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do evolutionary psychologists explain sex differences in sexuality?

Evolutionary psychologists theorize that females have inherited their ancestors’ tendencies to be more cautious, sexually, because of the challenges associated with incubating and nurturing offspring. Males have inherited an inclination to be more casual about sex, because their act of fathering requires a smaller investment.

- What are the three main criticisms of the evolutionary explanation of human sexuality?

(1) It starts with an effect and works backward to propose an explanation. (2) Unethical and immoral men could use such explanations to rationalize their behavior toward women. (3) This explanation may overlook the effects of cultural expectations and socialization.

151