4.3 Culture, Gender, and Other Environmental Influences

interaction the interplay that occurs when the effect of one factor (such as environment) depends on another factor (such as heredity).

From conception onward, we are the product of a cascade of interactions between our genetic predispositions and our surrounding environments (McGue, 2010). Our genes affect how people react to and influence us. Forget nature versus nurture; think nature via nurture.

Imagine two babies, one genetically predisposed to be attractive, sociable, and easygoing, the other less so. Assume further that the first baby attracts more affectionate and stimulating care and so develops into a warmer and more outgoing person. As the two children grow older, the more naturally outgoing child may seek more activities and friends that encourage further social confidence.

What has caused their resulting personality differences? Neither heredity nor experience acts alone. Environments trigger gene activity. And our genetically influenced traits evoke significant responses in others. Thus, a child’s impulsivity and aggression may evoke an angry response from a parent or teacher, who reacts warmly to model children in the family or classroom. In such cases, the child’s nature and the parents’ nurture interact. Gene and scene dance together.

152

Identical twins not only share the same genetic predispositions, they also seek and create similar experiences that express their shared genes (Kandler et al., 2012). Evocative interactions may help explain why identical twins raised in different families recall their parents’ warmth as remarkably similar—

How Does Experience Influence Development?

Our genes, when expressed in specific environments, influence our developmental differences. We are not “blank slates” (Kenrick et al., 2009). We are more like coloring books, with certain lines predisposed and experience filling in the full picture. We are formed by nature and nurture. But what are the most influential components of our nurture? How do our early experiences, our family and peer relationships, and all our other experiences guide our development and contribute to our diversity?

The formative nurture that conspires with nature begins at conception, with the prenatal environment in the womb, where embryos receive differing nutrition and varying levels of exposure to toxic agents. Nurture then continues outside the womb, where our early experiences foster brain development.

Experience and Brain Development

4-

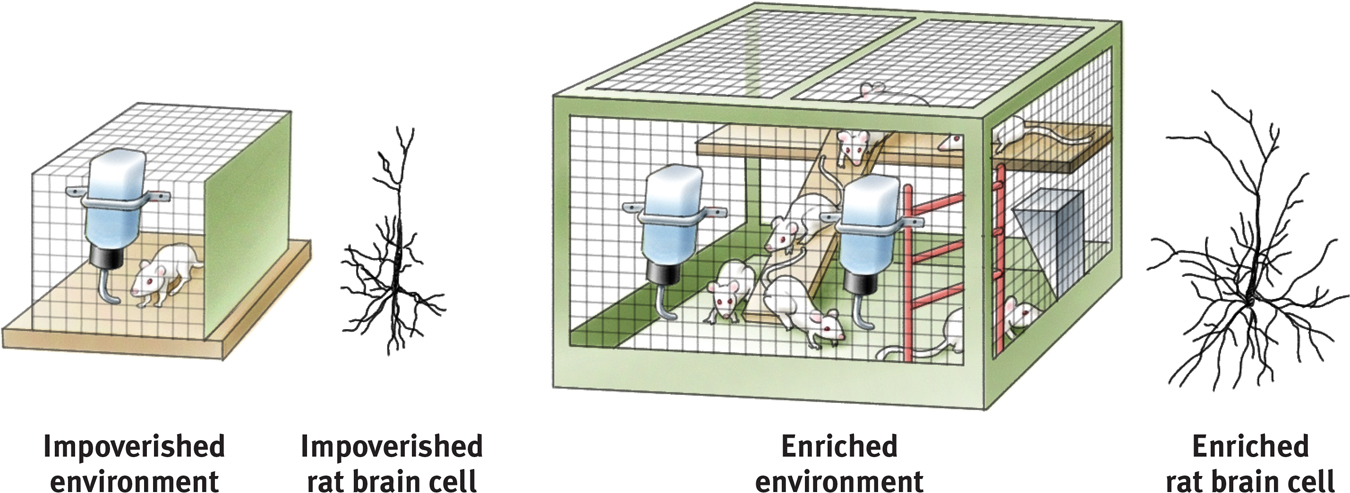

Our genes dictate our overall brain architecture, but experience fills in the details. Developing neural connections prepare our brain for thought, language, and other later experiences. So how do early experiences leave their “fingerprints” in the brain? Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) opened a window on that process when they raised some young rats in solitary confinement and others in a communal playground. When they later analyzed the rats’ brains, those who died with the most toys had won. The rats living in the enriched environment, which simulated a natural environment, usually developed a heavier and thicker brain cortex (FIGURE 4.4).

Figure 4.4

Figure 4.4Experience affects brain development Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) raised rats either alone in an environment without playthings, or with other rats in an environment enriched with playthings changed daily. In 14 of 16 repetitions of this basic experiment, rats in the enriched environment developed significantly more cerebral cortex (relative to the rest of the brain’s tissue) than did those in the impoverished environment.

Rosenzweig was so surprised by this discovery that he repeated the experiment several times before publishing his findings (Renner & Rosenzweig, 1987; Rosenzweig, 1984). So great are the effects that, shown brief video clips of rats, you could tell from their activity and curiosity whether their environment had been impoverished or enriched (Renner & Renner, 1993). After 60 days in the enriched environment, the rats’ brain weights increased 7 to 10 percent and the number of synapses mushroomed by about 20 percent (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998).

153

Such results have motivated improvements in environments for laboratory, farm, and zoo animals—

Nature and nurture interact to sculpt our synapses. Brain maturation provides us with an abundance of neural connections. Experiences trigger sights and smells, touches and tugs, and activate and strengthen connections. Unused neural pathways weaken. Like forest pathways, popular tracks are broadened and less-

Here at the juncture of nurture and nature is the biological reality of early childhood learning. During early childhood—

“Genes and experiences are just two ways of doing the same thing—

Joseph LeDoux, The Synaptic Self, 2002

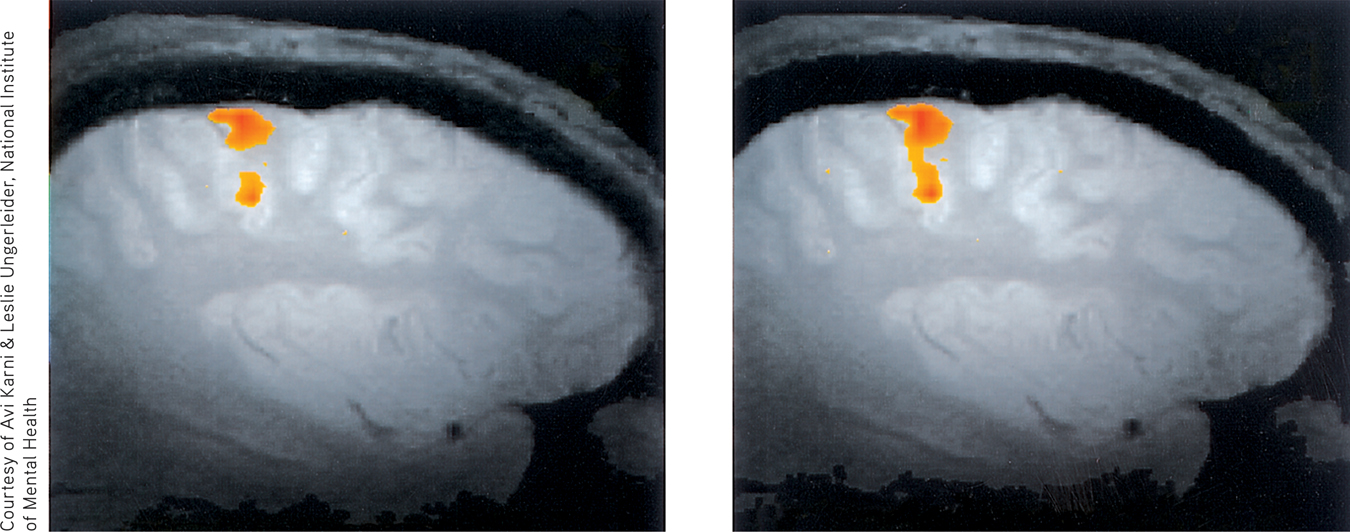

Although normal stimulation during the early years is critical, the brain’s development does not end with childhood. Thanks to the brain’s amazing plasticity, our neural tissue is ever changing and reorganizing in response to new experiences. New neurons are also born. If a monkey pushes a lever with the same finger many times a day, brain tissue controlling that finger will change to reflect the experience (FIGURE 4.5). Human brains work similarly. Whether learning to keyboard, skateboard, or navigate London’s streets, we perform with increasing skill as our brain incorporates the learning (Ambrose, 2010; Maguire et al., 2000).

Figure 4.5

Figure 4.5A trained brain A well-

How Much Credit or Blame Do Parents Deserve?

4-

In procreation, a woman and a man shuffle their gene decks and deal a life-

154

But do parents really produce future adults with an inner wounded child by being (take your pick from the toxic-

Parents do matter. But parenting wields its largest effects at the extremes: the abused children who become abusive, the neglected who become neglectful, the loved but firmly handled who become self-

Yet in personality measures, shared environmental influences from the womb onward typically account for less than 10 percent of children’s differences. In the words of behavior geneticists Robert Plomin and Denise Daniels (1987; Plomin, 2011), “Two children in the same family are [apart from their shared genes] as different from one another as are pairs of children selected randomly from the population.” To developmental psychologist Sandra Scarr (1993), this implied that “parents should be given less credit for kids who turn out great and blamed less for kids who don’t.” Knowing children are not easily sculpted by parental nurture, perhaps parents can relax a bit more and love their children for who they are.

Peer Influence

As children mature, what other experiences do the work of nurturing? At all ages, but especially during childhood and adolescence, we seek to fit in with our groups (Harris, 1998, 2000):

- Preschoolers who disdain a certain food often will eat that food if put at a table with a group of children who like it.

- Children who hear English spoken with one accent at home and another in the neighborhood and at school will invariably adopt the accent of their peers, not their parents. Accents (and slang) reflect culture, “and children get their culture from their peers,” as Judith Rich Harris (2007), has noted.

- Teens who start smoking typically have friends who model smoking, suggest its pleasures, and offer cigarettes (J. S. Rose et al., 1999; R. J. Rose et al., 2003). Part of this peer similarity may result from a selection effect, as kids seek out peers with similar attitudes and interests. Those who smoke (or don’t) may select as friends those who also smoke (or don’t).

“Men resemble the times more than they resemble their fathers.”

Ancient Arab proverb

- Put two teens together and their brains become hypersensitive to reward (Albert et al., 2013). This increased activation helps explain why teens take more driving risks when with friends than they do when alone (Chein et al., 2011).

155

Howard Gardner (1998) has concluded that parents and peers are complementary:

Parents are more important when it comes to education, discipline, responsibility, orderliness, charitableness, and ways of interacting with authority figures. Peers are more important for learning cooperation, for finding the road to popularity, for inventing styles of interaction among people of the same age. Youngsters may find their peers more interesting, but they will look to their parents when contemplating their own futures. Moreover, parents [often] choose the neighborhoods and schools that supply the peers.

This power to select a child’s neighborhood and schools gives parents an ability to influence the culture that shapes the child’s peer group. And because neighborhood influences matter, parents may want to become involved in intervention programs that aim at a whole school or neighborhood. If the vapors of a toxic climate are seeping into a child’s life, that climate—

Question

hxq6054egXLkPp5bJGWs9If/7ox8+BZYfsRdGGQvDDu9PZzYPlFEkfNA3KpJM32tXgvbekUe8L08AX1Aq+FPWsQOZfzPeV9P8nNzJyFNCtUaBt5QU067z4sRAxOl4IPCUhzhNuJrFs8dZpmoWIgyNt51nBAz4/sS40BlGPhLCWy9jUuQQulpYxUbxUIPMeLPca6OLzMfW+OyiXzkQ8PbLJkECPT/HP071CZdQcfPSmhaOTnYV2T+HkLTuK050aWcbqHwNLjhsissbvP3E5CAKhSXjy5yr2UnrpTFd/c2cAcMFWPFZIiNtX1gJPJqgBw8RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

What is the selection effect, and how might it affect a teen’s decision to drink alcohol?

Adolescents tend to select out similar others and sort themselves into like-

Cultural Influences

4-

culture the enduring behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next.

Compared with the narrow path taken by flies, fish, and foxes, the road along which environment drives us is wider. The mark of our species—

Culture is the behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next (Brislin, 1988; Cohen, 2009). Human nature, noted Roy Baumeister (2005), seems designed for culture. We are social animals, but more. Wolves are social animals; they live and hunt in packs. Ants are incessantly social, never alone. But “culture is a better way of being social,” noted Baumeister. Wolves function pretty much as they did 10,000 years ago. You and I enjoy things unknown to most of our century-

Other animals exhibit smaller kernels of culture. Primates have local customs of tool use, grooming, and courtship. Chimpanzees sometimes invent customs using leaves to clean their bodies, slapping branches to get attention, and doing a “rain dance” by slowly displaying themselves at the start of rain and pass them on to their peers and offspring (Whiten et al., 1999). Culture supports a species’ survival and reproduction by transmitting learned behaviors that give a group an edge. But human culture does more.

Thanks to our mastery of language, we humans enjoy the preservation of innovation. Within the span of this day, we have used Google, laser printers, digital hearing technology [DM], and a GPS running watch [ND]. On a grander scale, we have culture’s accumulated knowledge to thank for the last century’s 30-

156

Across cultures, we differ in our language, our monetary systems, our sports, even which side of the road we drive on. But beneath these differences is our great similarity—

Variation Across Cultures

We see our adaptability in cultural variations among our beliefs and our values, in how we nurture our children and bury our dead, and in what we wear (or whether we wear anything at all). We are ever mindful that the readers of this book are culturally diverse. You and your ancestors reach from Australia to Africa and from Singapore to Sweden.

norm an understood rule for accepted and expected behavior. Norms prescribe “proper” behavior.

Riding along with a unified culture is like running with the wind: As it carries us along, we hardly notice it is there. When we try running against the wind we feel its force. Face to face with a different culture, we become aware of the cultural winds. Visiting Europe, most North Americans notice the smaller cars, the left-

But humans in varied cultures nevertheless share some basic moral ideas. Even before they can walk, babies prefer helpful people over naughty ones (Hamlin et al., 2011). Yet each cultural group also evolves its own norms—rules for accepted and expected behavior. The British have a norm for orderly waiting in line. Many South Asians use only the right hand’s fingers for eating. Sometimes social expectations seem oppressive: “Why should it matter how I dress?” Yet, norms grease the social machinery and free us from self-

When cultures collide, their differing norms often befuddle. Should we greet people by shaking hands, bowing, or kissing each cheek? Knowing what sorts of gestures and compliments are culturally appropriate, we can relax and enjoy one another without fear of embarrassment or insult.

When we don’t understand what’s expected or accepted, we may experience culture shock. People from Mediterranean cultures have perceived northern Europeans as efficient but cold and preoccupied with punctuality (Triandis, 1981). People from time-

Variation Over Time

Like biological creatures, cultures vary and compete for resources, and thus evolve over time (Mesoudi, 2009). Consider how rapidly cultures may change. English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (1342–1400) is separated from a modern Briton by only 20 generations, but the two would have great difficulty speaking. In the thin slice of history since 1960, most Western cultures have changed with remarkable speed. Middle-

157

But some changes seem not so wonderfully positive. Had you fallen asleep in the United States in 1960 and awakened today, you would open your eyes to a culture with more divorce and depression. You would also find North Americans—

Whether we love or loathe these changes, we cannot fail to be impressed by their breathtaking speed. And we cannot explain them by changes in the human gene pool, which evolves far too slowly to account for high-

Culture and the Self

4-

individualism giving priority to one’s own goals over group goals and defining one’s identity in terms of personal attributes rather than group identifications.

Imagine that someone ripped away your social connections, making you a solitary refugee in a foreign land. How much of your identity would remain intact?

If you are an individualist, a great deal of your identity would remain intact. You would have an independent sense of “me,” and an awareness of your unique personal convictions and values. Individualists give higher priority to personal goals. They define their identity mostly in terms of personal traits. They strive for personal control and individual achievement.

Individualism is valued in most areas of North America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. The United States is mostly an individualist culture. Founded by settlers who wanted to differentiate themselves from others, Americans have cherished the “pioneer” spirit (Kitayama et al., 2010). Some 85 percent of Americans say it is possible “to pretty much be who you want to be” (Sampson, 2000).

Individualists share the human need to belong. They join groups. But they are less focused on group harmony and doing their duty to the group (Brewer & Chen, 2007). Being more self-

collectivism giving priority to the goals of one’s group (often one’s extended family or work group) and defining one’s identity accordingly.

Although individuals within cultures vary, different cultures emphasize either individualism or collectivism. If set adrift in a foreign land as a collectivist, you might experience a greater loss of identity. Cut off from family, groups, and loyal friends, you would lose the connections that have defined who you are. Group identifications provide a sense of belonging, a set of values, and an assurance of security in collectivist cultures. In return, collectivists have deeper, more stable attachments to their groups—

Collectivists are like athletes who take more pleasure in their team’s victory than in their own performance. They find satisfaction in advancing their groups’ interests, even at the expense of personal needs. Preserving group spirit and avoiding social embarrassment are important goals. Collectivists therefore avoid direct confrontation, blunt honesty, and uncomfortable topics. They value humility, not self-

“One needs to cultivate the spirit of sacrificing the little me to achieve the benefits of the big me.”

Chinese saying

158

To be sure, there is diversity within cultures. Within many countries, there are also distinct subcultures related to one’s religion, economic status, and region (Cohen, 2009). In China, greater collectivist thinking occurs in provinces that produce large amounts of rice, a difficult-

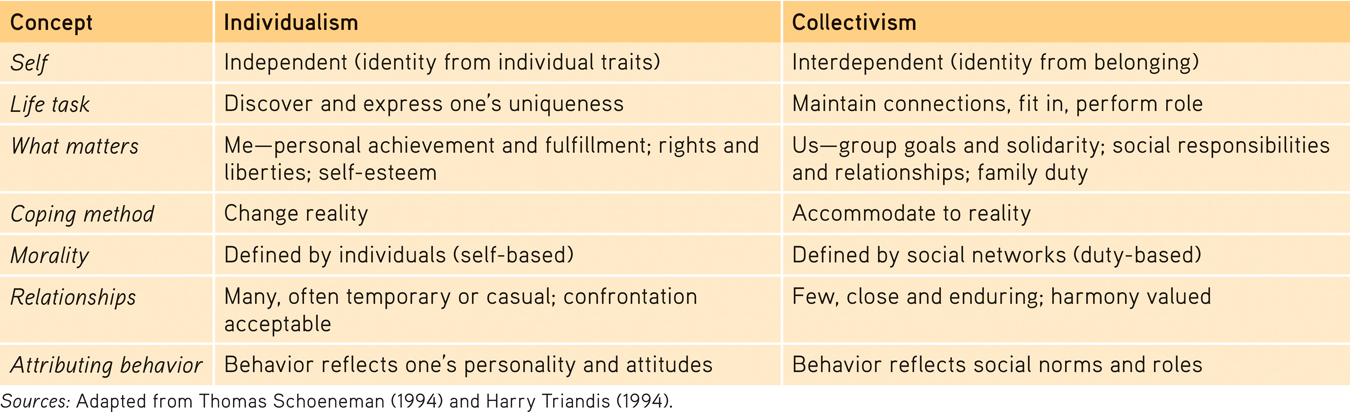

Table 4.2

Table 4.2Value Contrasts Between Individualism and Collectivism

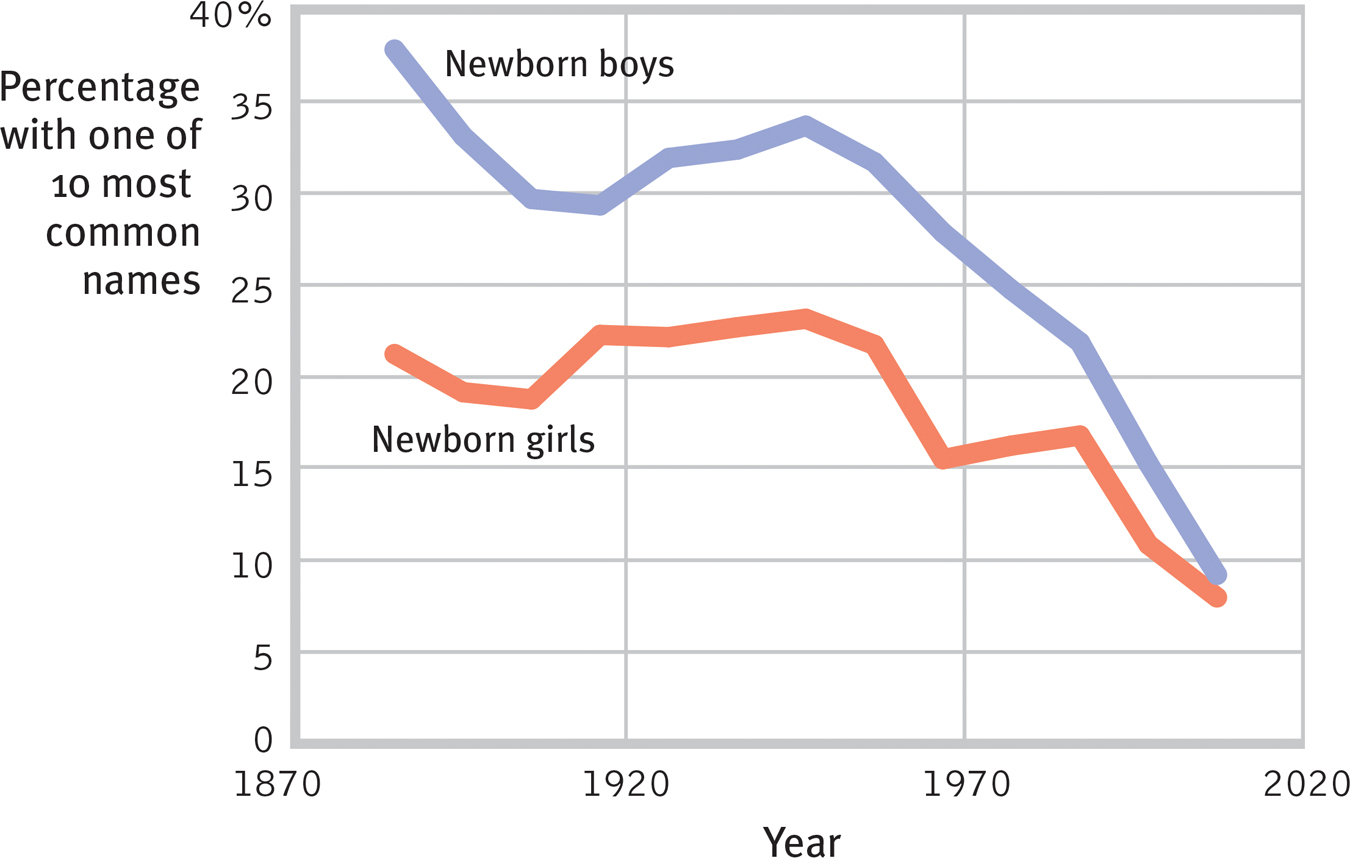

Individualists even prefer unusual names, as psychologist Jean Twenge noticed while seeking a name for her first child. Over time, the most common American names listed by year on the U.S. Social Security baby names website were becoming less desirable. When she and her colleagues (2010) analyzed the first names of 325 million American babies born between 1880 and 2007, they confirmed this trend. As FIGURE 4.6 illustrates, the percentage of boys and girls given one of the 10 most common names for their birth year has plunged, especially in recent years. Even within the United States, parents from more recently settled states (for example, Utah and Arizona) give their children more distinct names compared with parents who live in more established states (for example, New York and Massachusetts) (Varnum & Kitayama, 2011).

Figure 4.6

Figure 4.6A child like no other Americans’ individualist tendencies are reflected in their choice of names for their babies. In recent years, the percentage of American babies receiving one of that year’s 10 most common names has plunged. (Data from Twenge et al., 2010.)

159

The individualist–collectivist divide appeared in reactions to medals received during the 2000 and 2002 Olympic games. U.S. gold medal winners and the U.S. media covering them attributed the achievements mostly to the athletes themselves (Markus et al., 2006). “I think I just stayed focused,” explained swimming gold medalist Misty Hyman. “It was time to show the world what I could do. I am just glad I was able to do it.” Japan’s gold medalist in the women’s marathon, Naoko Takahashi, had a different explanation: “Here is the best coach in the world, the best manager in the world, and all of the people who support me—

There has been more loneliness, divorce, homicide, and stress-

As cultures evolve, some trends weaken and others grow stronger. In Western cultures, individualism increased strikingly over the last century. This trend reached a new high in 2012, when U.S. high school and college students reported the greatest-

What predicts changes in one culture over time, or between differing cultures? Social history matters. In Western cultures, individualism and independence have been fostered by voluntary migration, a capitalist economy, and a sparsely populated, challenging environment (Kitayama et al., 2009, 2010; Varnum et al., 2010). Might biology also play a role? In search of biological underpinnings to such cultural differences—

160

Culture and Child Raising

Child-

Children across place and time have thrived under various child-

Many Asians and Africans live in cultures that value emotional closeness. Infants and toddlers may sleep with their mothers and spend their days close to a family member (Morelli et al., 1992; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). These cultures encourage a strong sense of family self—a feeling that what shames the child shames the family, and what brings honor to the family brings honor to the self.

In the African Gusii society, babies nurse freely but spend most of the day on their mother’s back—

Developmental Similarities Across Groups

Mindful of how others differ from us, we often fail to notice the similarities predisposed by our shared biology. One 49-

161

Even differences within a culture, such as those sometimes attributed to race, are often easily explained by an interaction between our biology and our culture. David Rowe and his colleagues (1994, 1995) illustrated this with an analogy: Black men tend to have higher blood pressure than White men. Suppose that (1) in both groups, salt consumption correlates with blood pressure, and (2) salt consumption is higher among Black men than among White men. The blood pressure “race difference” might then actually be, at least partly, a diet difference—

“When [someone] has discovered why men in Bond Street wear black hats he will at the same moment have discovered why men in Timbuctoo wear red feathers.”

G. K. Chesterton, Heretics, 1905

And that, said Rowe and his colleagues, parallels psychological findings. Although Latino, Asian, Black, White, and Native Americans differ in school achievement and delinquency, the differences are “no more than skin deep.” To the extent that family structure, peer influences, and parental education predict behavior in one of these ethnic groups, they do so for the others as well.

So as members of different ethnic and cultural groups, we may differ in surface ways. But as members of one species we seem subject to the same psychological forces. Our languages vary, yet they reflect universal principles of grammar. Our tastes vary, yet they reflect common principles of hunger. Our social behaviors vary, yet they reflect pervasive principles of human influence. Cross-

Question

Cr8QiQGiwT/wQGxALYsIyP3AgZHGoX1KuOFmI1urUUYNmgkvwEMpyWV29VNNa1ZHCaT+Dt18wcxfKNvFuRqoLudXn6Sok8i0Tk/CsajPpxjqZxsho/qe2XXrurC/ZITlcOtyB+u64g+JcdcqmqEICJ5+ylBKrjkryD33ostLV+L6HNM9Z1VAcbAtynT2d//epmtFbTB+fIqbAE18L2n8BnLaTM4+c9DxEuq0cqrTEN6rte6AWJy4o1tp68GUDpombSh5CyePov9k23T4DU2a2k/w3XPYX9KJzaYnIV9M/TpsPSQBRBctGdAQ3x2H5HH5RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do individualist and collectivist cultures differ?

Individualists give priority to personal goals over group goals and tend to define their identity in terms of their own personal attributes. Collectivists give priority to group goals over individual goals and tend to define their identity in terms of group identifications.

Gender Development

sex in psychology, the biologically influenced characteristics by which people define males and females.

4-

gender in psychology, the socially influenced characteristics by which people define men and women.

We humans share an irresistible urge to organize our worlds into simple categories. Among the ways we classify people—

Our gender is the product of the interplay among our biological dispositions, our developmental experiences, and our current situations (Eagly & Wood, 2013). Before we consider that interplay in more detail, let’s take a closer look at some ways that males and females are both similar and different.

Similarities and Differences

4-

Whether male or female, each of us receives 23 chromosomes from our mother and 23 from our father. Of those 46 chromosomes, 45 are unisex. Our similar biology helped our evolutionary ancestors face similar adaptive challenges. Both men and women needed to survive, reproduce, and avoid predators, and so today we are in most ways alike. Tell me whether you are male or female and you give me no clues to your vocabulary, happiness, or ability to see, hear, learn, and remember. Women and men, on average, have comparable creativity and intelligence and feel the same emotions and longings. Our “opposite” sex is, in reality, our very similar sex.

Pink and blue baby outfits illustrate how cultural norms vary and change. “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boy and blue for the girl,” declared the Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department in June of 1918 (Frassanito & Pettorini, 2008). “The reason is that pink being a more decided and stronger color is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girls.”

162

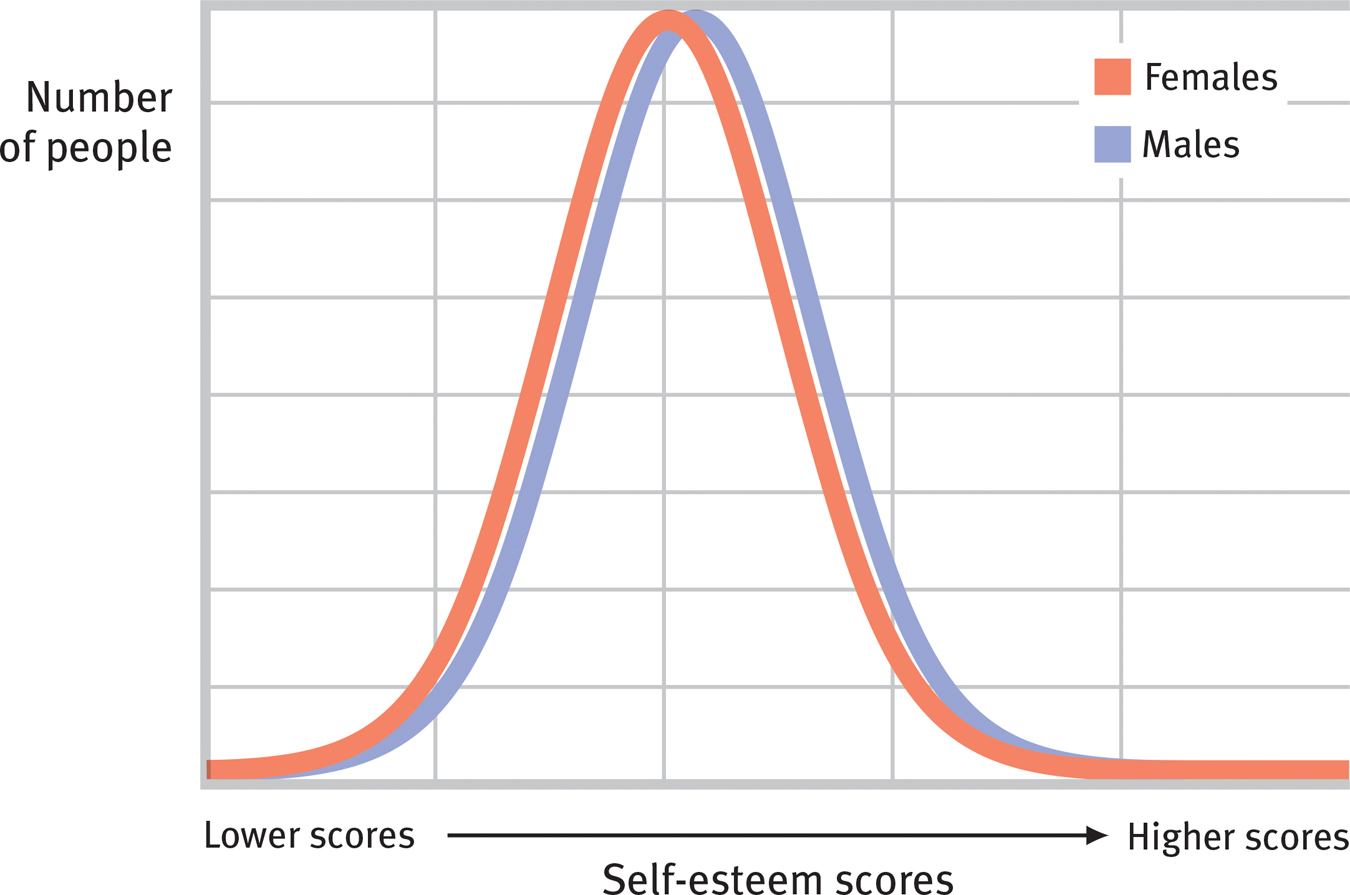

Figure 4.7

Figure 4.7Much ado about a small difference in self-

But in some areas, males and females do differ, and differences command attention. Some much talked-

aggression any physical or verbal behavior intended to harm someone physically or emotionally.

Let’s take a closer look at three areas—

Aggression To a psychologist, aggression is any physical or verbal behavior intended to hurt someone physically or emotionally. Think of some aggressive people you have heard about. Are most of them men? Men generally admit to more aggression. They also commit more extreme physical violence (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010). In romantic relationships between men and women, minor acts of physical aggression, such as slaps, are roughly equal—

relational aggression an act of aggression (physical or verbal) intended to harm a person’s relationship or social standing.

Laboratory experiments have demonstrated gender differences in aggression. Men have been more willing to blast people with what they believed was intense and prolonged noise (Bushman et al., 2007). And outside the laboratory, men—

Here’s another question: Think of examples of people harming others by passing along hurtful gossip, or by shutting someone out of a social group or situation. Were most of those people men? Perhaps not. Those behaviors are acts of relational aggression, and women are slightly more likely than men to commit them (Archer, 2004, 2007, 2009).

Social Power Imagine walking into a job interview. You sit down and peer across the table at your two interviewers. The unsmiling person on the left oozes self-

Which interviewer is male?

If you said the person on the left, you’re not alone. Around the world, from Nigeria to New Zealand, people have perceived gender differences in power (Williams & Best, 1990). Indeed, in most societies men do place more importance on power and achievement and are socially dominant (Schwartz & Rubel-

163

- When groups form, whether as juries or companies, leadership tends to go to males (Colarelli et al., 2006). And when salaries are paid, those in traditionally male occupations receive more.

- When people run for election, women who appear hungry for political power more than their equally power-

hungry male counterparts experience less success (Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010). And when elected, political leaders usually are men, who held 78 percent of the seats in the world’s governing parliaments in 2014 (IPU, 2014).

Men and women also lead differently. Men tend to be more directive, telling people what they want and how to achieve it. Women tend to be more democratic, more welcoming of others’ input in decision making (Eagly & Carli, 2007; van Engen & Willemsen, 2004). When interacting, men have been more likely to offer opinions, women to express support (Aries, 1987; Wood, 1987). In everyday behavior, men tend to act as powerful people often do: talking assertively, interrupting, initiating touches, and staring. And they smile and apologize less (Leaper & Ayres, 2007; Major et al., 1990; Schumann & Ross, 2010). Such behaviors help sustain men’s greater social power.

Women’s 2011 representations in national parliaments ranged from 13 percent in the Pacific region to 42 percent in Scandinavia (IPU, 2014).

Social Connectedness Whether male or female, we all have a need to belong, though we may satisfy this need in different ways (Baumeister, 2010). Males tend to be independent. Even as children, males typically form large play groups. Boys’ games brim with activity and competition, with little intimate discussion (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). As adults, men enjoy doing activities side by side, and they tend to use conversation to communicate solutions (Tannen, 1990; Wright, 1989). When asked a difficult question—

Question: Why does it take 200 million sperm to fertilize one egg?

Answer: Because they won’t stop for directions.

Females tend to be more interdependent. In childhood, girls usually play in small groups, often with one friend. They compete less and imitate social relationships more (Maccoby, 1990; Roberts, 1991). Teen girls spend more time with friends and less time alone (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). In late adolescence, they spend more time on social-

Brain scans suggest that women’s brains are better wired to improve social relationships, and men’s brains to connect perception with action (Ingalhalikar et al., 2013). The communication style gender difference is apparent even in electronic communication. In one New Zealand study of student e-

Do such findings mean that women are just more talkative? No. In another study, researchers counted the number of words 396 college students spoke in an average day (Mehl et al., 2007). Not surprisingly, the participants’ talkativeness varied enormously—

The words we use may not peg women or men as more talkative, but those words do open windows on our interests. Worldwide, women’s interests and vocations tilt more toward people and less toward things (Eagly, 2009; Lippa, 2005, 2006, 2008). In one analysis of over 700 million words collected from Facebook messages, women used more family-

164

In the workplace, women are less often driven by money and status and more apt to opt for reduced work hours (Pinker, 2008). In the home, they are five times more likely than men to claim primary responsibility for taking care of children (Time, 2009). Women’s emphasis on caring helps explain another interesting finding: Although 69 percent of people have said they have a close relationship with their father, 90 percent said they feel close to their mother (Hugick, 1989). When searching for understanding from someone who will share their worries and hurts, people usually turn to women. Both men and women have reported their friendships with women as more intimate, enjoyable, and nurturing (Kuttler et al., 1999; Rubin, 1985; Sapadin, 1988).

Bonds and feelings of support are even stronger among women than among men (Rossi & Rossi, 1993). Women’s ties—

As empowered people generally do, men value freedom and self-

The gender gap in both social connectedness and power peaks in late adolescence and early adulthood—

So, although women and men are more alike than different, there are some behavior differences between the average woman and man. Are such differences dictated by our biology? Shaped by our cultures and other experiences? Do we vary in the extent to which we are male or female? Read on.

“In the long years liker must they grow; The man be more of woman, she of man.”

Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Princess, 1847

Question

n9GNKt200BAPaxgTFefKh8y0m8uH2M6+5SFJMDBOOjbHQzEio8p9G3lkB7NaeFWwc4P6o/tKVeJrp0UE4RE08SmX/vGWB09i6k8dpHjW5UNL+lxCtbYpTUilzjcBx1uXkNJCM/Qbe6JdIUrZqvlBWdo0AdRrxf2jaFzgZRhJfmoJiu46XoUizMtvwEyGOq6IJ6jWr5D/2Xpb/oGIvuC/wCJ8OE9hUGPq7unoWkehXp70de7JO2mBF+WfyLDXJM/ynWh+uWhLV/Y2/MlCFhdFlMLX1c5CfyhUb+uMXzVPcfxu81t+8TedpoHt0cezgqpXmQiuIw==165

The Nature of Gender: Our Biological Sex

4-

Men and women employ similar solutions when faced with challenges: sweating to cool down, guzzling an energy drink or coffee to get going in the morning, or finding darkness and quiet to sleep. When looking for a mate, men and women also prize many of the same traits. They prefer having a mate who is “kind,” “honest,” and “intelligent.” But according to evolutionary psychologists, in mating-

Biology does not dictate gender, but it can influence it in two ways:

- Genetically—males and females have differing sex chromosomes.

- Physiologically—males and females have differing concentrations of sex hormones, which trigger other anatomical differences.

X chromosome the sex chromosome found in both men and women. Females have two X chromosomes; males have one. An X chromosome from each parent produces a female child.

These two sets of influences began to form you long before you were born, when your tiny body started developing in ways that determined your sex.

Y chromosome the sex chromosome found only in males. When paired with an X chromosome from the mother, it produces a male child.

Prenatal Sexual Development Six weeks after you were conceived, you and someone of the other sex looked much the same. Then, as your genes kicked in, your biological sex—

testosterone the most important of the male sex hormones. Both males and females have it, but the additional testosterone in males stimulates the growth of the male sex organs during the fetal period, and the development of the male sex characteristics during puberty.

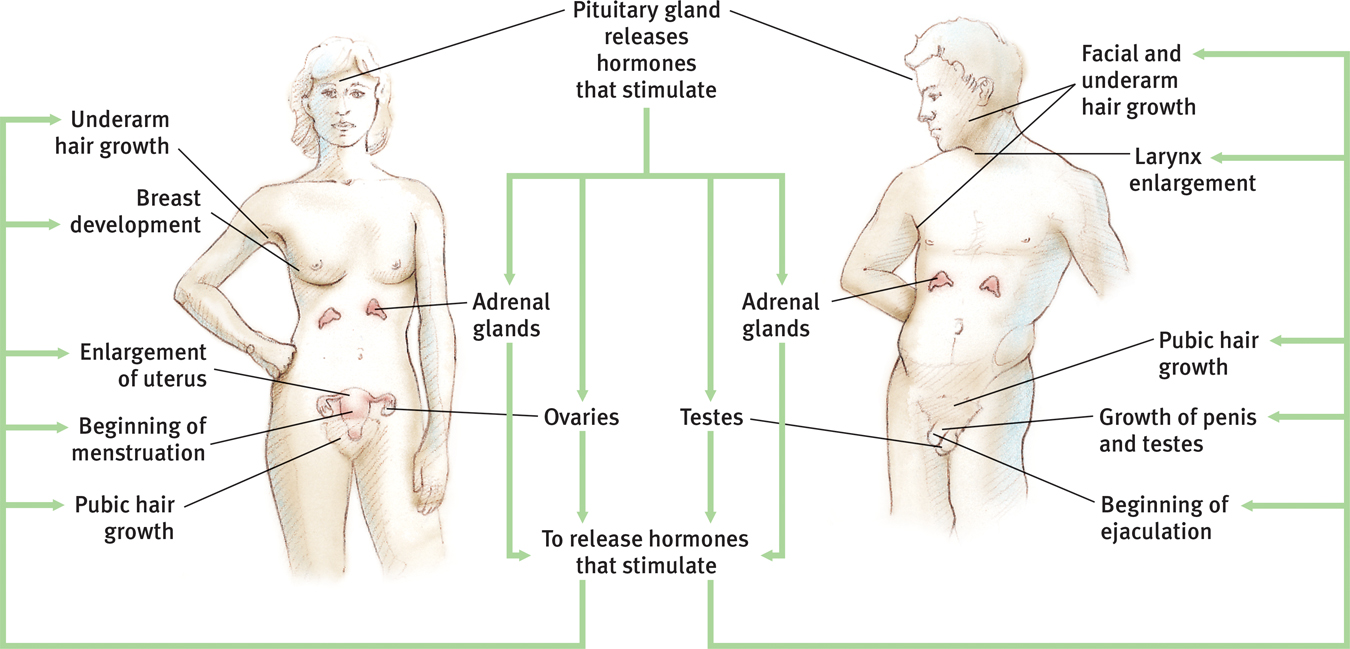

About seven weeks after conception, a single gene on the Y chromosome throws a master switch, which triggers the testes to develop and to produce testosterone, the principal male hormone that promotes development of male sex organs. (Females also have testosterone, but less of it.) The male’s greater testosterone output starts the development of external male sex organs at about the seventh week.

puberty the period of sexual maturation, when a person becomes capable of reproducing.

Later, during the fourth and fifth prenatal months, sex hormones bathe the fetal brain and influence its wiring. Different patterns for males and females develop under the influence of the male’s greater testosterone and the female’s ovarian hormones (Hines, 2004; Udry, 2000). Male-

primary sex characteristics the body structures (ovaries, testes, and external genitalia) that make sexual reproduction possible.

Adolescent Sexual Development A flood of hormones triggers another period of dramatic physical change during adolescence, when boys and girls enter puberty. In this two-

secondary sex characteristics nonreproductive sexual traits, such as female breasts and hips, male voice quality, and body hair.

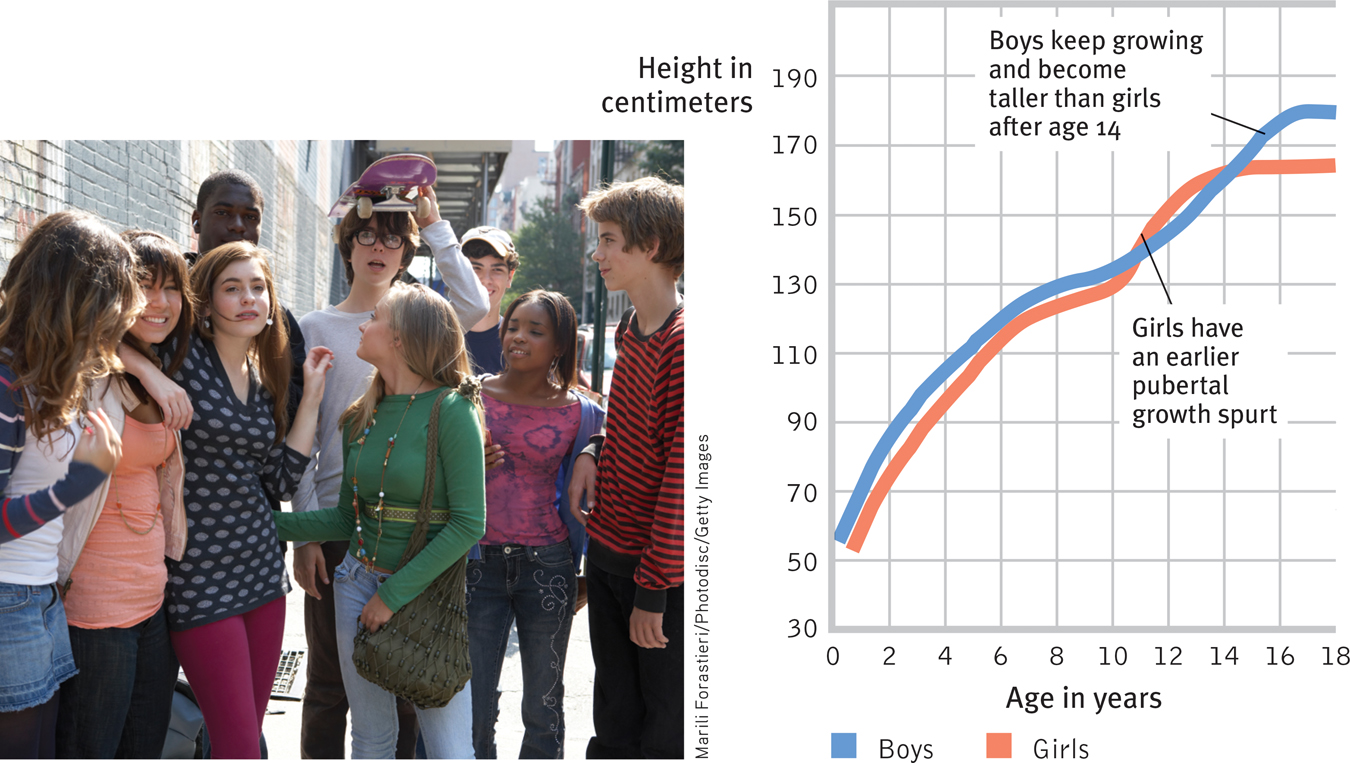

Girls’ slightly earlier entry into puberty can at first propel them to greater height than boys of the same age (FIGURE 4.8 below). But boys catch up when they begin puberty, and by age 14, they are usually taller than girls. During these growth spurts, the primary sex characteristics—the reproductive organs and external genitalia—

Figure 4.8

Figure 4.8Height differences Throughout childhood, boys and girls are similar in height. At puberty, girls surge ahead briefly, but then boys typically overtake them at about age 14. (Data from Tanner, 1978.) Studies suggest that sexual development and growth spurts are now beginning somewhat earlier than was the case a half-

Figure 4.9

Figure 4.9Body changes at puberty At about age 11 in girls and age 12 in boys, a surge of hormones triggers a variety of visible physical changes.

166

Pubertal boys may not at first like their sparse beard. (But then it grows on them.)

spermarche [sper-

menarche [meh-

For boys, puberty’s landmark is the first ejaculation, which often occurs first during sleep (as a “wet dream”). This event, called spermarche (sper-

In girls, the landmark is the first menstrual period (menarche—meh-

167

Girls prepared for menarche usually experience it positively (Chang et al., 2009). Most women recall their first menstrual period with mixed emotions—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Adolescence is marked by the onset of ______________.

puberty

For a 7-

For a 7-

disorder of sexual development an inherited condition that involves unusual development of sex chromosomes and anatomy.

Sexual Development Variations Sometimes nature blurs the biological line between males and females. When a fetus is exposed to unusual levels of sex hormones, or is especially sensitive to those hormones, the individual may develop a disorder of sexual development, with chromosomes or anatomy not typically male or female. A genetic male may be born with normal male hormones and testes but no penis or a very small one.

In the past, medical professionals often recommended sex-

Sex-

The bottom line: “Sex matters,” concluded the National Academy of Sciences (2001). Sex-

Question

vteX2D+In/KmMLTqvpzeBpo3uCImrQ1Ludjyf0YYjvMXp2u5FJWOaeZD4ggRrL6K6xamBycmWUp0OfQjoZqLk85gfiW4v1Pd5OrR3upuB/uExetA8x5kL2bx4rmRfTKvqCCvRs2iQ29W8ryeh0TO5/JOm8EgY3N0p3jTOdV1Z955qqjZ23E3Eatd+CT4Hlujx+ovaDwwu6RZ2p00bCl67Q9nEHIS6JlV0UbE6419uGV5/ZsfwT/Si5ytI57pyRgWdMaX77G1Bss=The Nurture of Gender: Our Culture and Experiences

4-

role a set of expectations (norms) about a social position, defining how those in the position ought to behave.

For many people, biological sex and gender coexist in harmony. Biology draws the outline, and culture paints the details. The physical traits that define us as biological males or females are the same worldwide. But the gender traits that define how men (or boys) and women (or girls) should act, interact, or feel about themselves may differ from one place to another (APA, 2009).

gender role a set of expected behaviors, attitudes, and traits for males or for females.

Gender Roles Cultures shape our behaviors by defining how we ought to behave in a particular social position, or role. We can see this shaping power in gender roles—the social expectations that guide our behavior as men or as women. Gender roles shift over time. A century ago, North American women could not vote in national elections, serve in the military, or divorce a husband without cause. And if a woman worked for pay outside the home, she would more likely have been a midwife or a seamstress, rather than a surgeon or a fashion designer.

168

Gender roles can change dramatically in a thin slice of history. At the beginning of the twentieth century, only one country in the world—

Gender roles also vary from one place to another. Nomadic societies of food-

gender identity our sense of being male, female, or a combination of the two.

Take a minute to check your own gender expectations. Would you agree that “When jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to a job”? In the United States, Britain, and Spain, barely over 12 percent of adults agree. In Nigeria, Pakistan, and India, about 80 percent of adults agree (Pew, 2010). We’re all human, but my how our views differ. Australia and the Scandinavian countries offer the greatest gender equity, Middle Eastern and North African countries the least (Social Watch, 2006).

social learning theory the theory that we learn social behavior by observing and imitating and by being rewarded or punished.

How Do We Learn Gender? A gender role describes how others expect us to think, feel, and act. Our gender identity is our personal sense of being male, female, or a combination of the two. How do we develop that personal viewpoint?

gender typing the acquisition of a traditional masculine or feminine role.

Social learning theory assumes that we acquire our gender identity in childhood, by observing and imitating others’ gender-

androgyny displaying both traditional masculine and feminine psychological characteristics.

169

How we feel matters, but so does how we think. Early in life, we form schemas, or concepts that help us make sense of our world. Our gender schemas organized our experiences of male-

As a young child, you (like other children) were a “gender detective” (Martin & Ruble, 2004). Before your first birthday, you knew the difference between a male and female voice or face (Martin et al., 2002). After you turned 2, language forced you to label the world in terms of gender. If you are an English speaker, you learned to classify people as he and she. If you are a French speaker, you learned also to classify objects as masculine (“le train”) or feminine (“la table”).

transgender an umbrella term describing people whose gender identity or expression differs from that associated with their birth sex.

Once children grasp that two sorts of people exist—

For a transgender person, comparing one’s personal gender identity with cultural concepts of gender roles produces feelings of confusion and discord. A transgender person’s gender identity differs from the behaviors or traits considered typical for that person’s birth sex (APA, 2010; Bockting, 2014). A person who was born a female may feel he is a man living in a woman’s body, or a person born male may feel she is a woman living in a man’s body. Some transgender people are also transsexual: They prefer to live as members of the other birth sex. Some transsexual people (about three times as many men as women) may seek medical treatment (including sex-

170

“The more I was treated as a woman, the more woman I became.”

Writer Jan Morris, male-

Note that gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation (the direction of one’s sexual attraction). Transgender people may be sexually attracted to people of the opposite birth sex (heterosexual), the same birth sex (homosexual), both sexes (bisexual), or to no one at all (asexual).

Transgender people may express their gender identity by dressing as a person of the other biological sex typically would. Most who dress this way are biological males who are attracted to women (APA, 2010).

Question

yX2QI9eK92fV93CAy3HSx+N1U+OA94OQDogsdJJlZB2RsfPiCtvM4QFYDqdb+bEpcqMd7URUIefG4B6eScj7uuIJmZfwyWWIJ1WNdzJcMAICmW8Cf8/wRoyrTt5fce5ya5u4oaYwAZomb6qDz6CspleBDM+C9edLvUZ1bGqeFeZyqmJ3yz5OcnLCR/tmHnlVdvVhdeVRHrfKQVXMlRNOKaZLBxXkEaOxLpBEHfadxgkrSyLjj8uThOtK0fjJ8eXywwc+GaqwXQpDqBy9MlLBiaV5nVzKb5JNFPTE4GZWKxhQF/VPVMpulWbBj4LBB3DqLFuI5n9ctk+jMWJXrujZR5fLa9TqGCwCafHMeBsI/wcv7N7NTQMdHA==RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

What are gender roles, and what do their variations tell us about our human capacity for learning and adaptation?

Gender roles are social rules or norms for accepted and expected behavior for females and males. The norms associated with various roles, including gender roles, vary widely in different cultural contexts, which is proof that we are very capable of learning and adapting to the social demands of different environments.

Reflections on Nature, Nurture, and Their Interaction

4-

“There are trivial truths and great truths,” reflected the physicist Niels Bohr on the paradoxes of science. “The opposite of a trivial truth is plainly false. The opposite of a great truth is also true.” Our ancestral history helped form us as a species. Where there is variation, natural selection, and heredity, there will be evolution. The unique gene combination created when our mother’s egg engulfed our father’s sperm predisposed both our shared humanity and our individual differences. Our genes form us. This is a great truth about human nature.

171

But our experiences also shape us. Our families and peer relationships teach us how to think and act. Differences initiated by our nature may be amplified by our nurture. If their genes and hormones predispose males to be more physically aggressive than females, culture can amplify this gender difference through norms that shower benefits on macho men and gentle women. If men are encouraged toward roles that demand physical power, and women toward more nurturing roles, each may act accordingly. Roles remake their players. Presidents in time become more presidential, servants more servile. Gender roles similarly shape us.

In many modern cultures, gender roles are merging. Brute strength is becoming increasingly less important for power and status (think Mark Zuckerberg and Hillary Clinton). From 1960 into the next century, women soared from 6 percent to nearly 50 percent of U.S. medical school graduates (AAMC, 2012). In the mid-

If nature and nurture jointly form us, are we “nothing but” the product of nature and nurture? Are we rigidly determined?

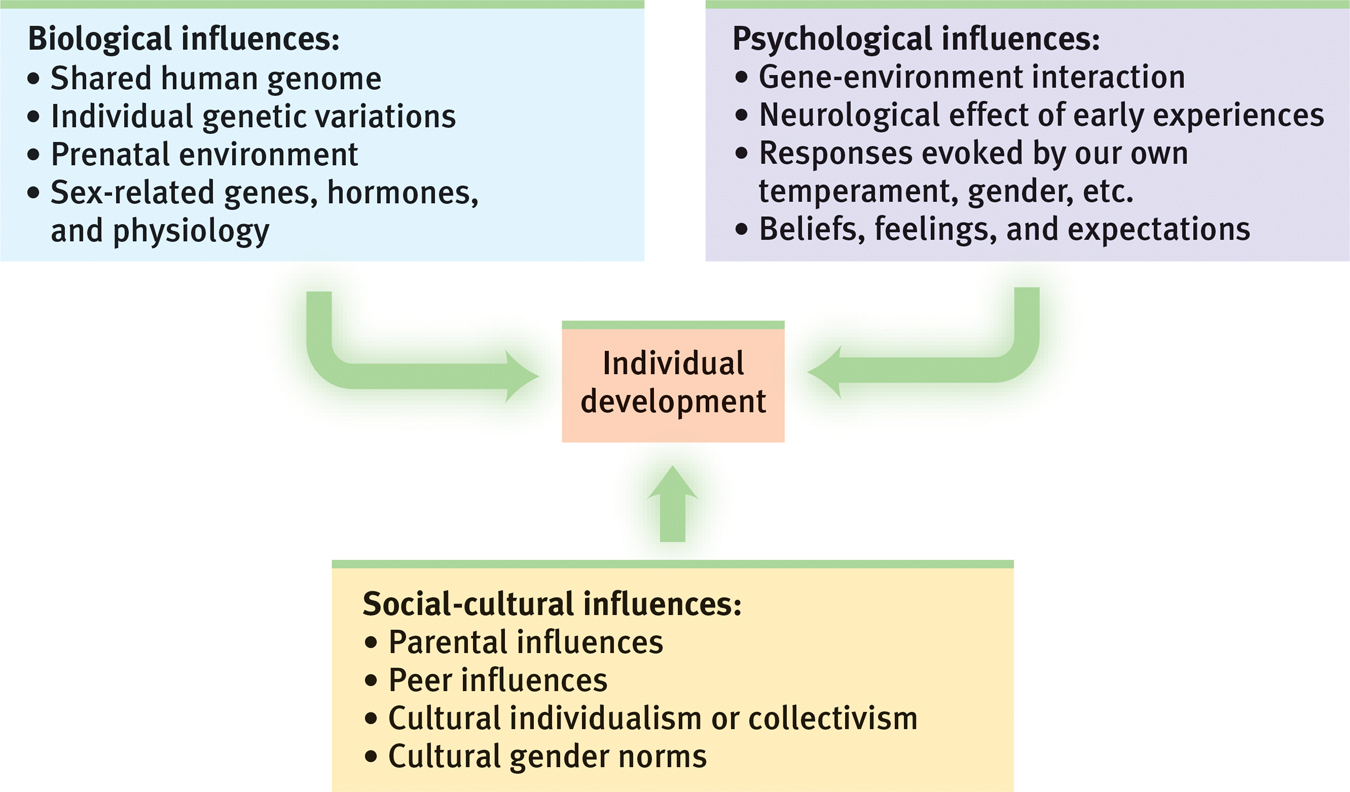

We are the product of nature and nurture, but we are also an open system (FIGURE 4.10 below). Genes are all-

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.10The biopsychosocial approach to development

We can’t excuse our failings by blaming them solely on bad genes or bad influences. In reality, we are both the creatures and the creators of our worlds. So many things about us—

172

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

How does the biopsychosocial approach explain our individual development?

The biopsychosocial approach considers all the factors that influence our individual development: biological factors (including evolution and our genes, hormones, and brain), psychological factors (including our experiences, beliefs, feelings, and expectations), and social-

***

“Let’s hope that it’s not true; but if it is true, let’s hope that it doesn’t become widely known.”

Lady Ashley, commenting on Darwin’s theory

We know from our correspondence and from surveys that some readers feel troubled by the naturalism and evolutionism of contemporary science. (Readers from other nations bear with us, but in the United States there is a wide gulf between scientific and lay thinking about evolution.) “The idea that human minds are the product of evolution is … unassailable fact,” declared a 2007 editorial in Nature, a leading science journal. That sentiment concurs with a 2006 statement of “evidence-

When Isaac Newton explained the rainbow in terms of light of differing wavelengths, the British poet John Keats feared that Newton had destroyed the rainbow’s mysterious beauty. Yet, as Richard Dawkins (1998) noted in Unweaving the Rainbow, Newton’s analysis led to an even deeper mystery—

“Is it not stirring to understand how the world actually works—

Carl Sagan, Skies of Other Worlds, 1988

When Galileo assembled evidence that the Earth revolved around the Sun, not vice versa, he did not offer irrefutable proof for his theory. Rather, he offered a coherent explanation for a variety of observations, such as the changing shadows cast by the Moon’s mountains. His explanation eventually won the day because it described and explained things in a way that made sense, that hung together. Darwin’s theory of evolution likewise is a coherent view of natural history. It offers an organizing principle that unifies various observations.

173

Collins is not the only person of faith to find the scientific idea of human origins congenial with his spirituality. In the fifth century, St. Augustine (quoted by Wilford, 1999) wrote, “The universe was brought into being in a less than fully formed state, but was gifted with the capacity to transform itself from unformed matter into a truly marvelous array of structures and life forms.” Some 1600 years later, Pope John Paul II in 1996 welcomed a science-

Meanwhile, many people of science are awestruck at the emerging understanding of the universe and the human creature. It boggles the mind—

What caused this almost-

“The causes of life’s history [cannot] resolve the riddle of life’s meaning.”

Stephen Jay Gould, Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life, 1999

Rather than fearing science, we can welcome its enlarging our understanding and awakening our sense of awe. In The Fragile Species, Lewis Thomas (1992) described his utter amazement that the Earth in time gave rise to bacteria and eventually to Bach’s Mass in B Minor. In a short 4 billion years, life on Earth has come from nothing to structures as complex as a 6-

174