5.3 Adolescence

adolescence the transition period from childhood to adulthood, extending from puberty to independence.

5-

Many psychologists once believed that childhood sets our traits. Today’s developmental psychologists see development as lifelong. As this life-

204

How will you look back on your life 10 years from now? Are you making choices that someday you will recollect with satisfaction?

In industrialized countries, what are the teen years like? In Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, the teen years were “that blissful time when childhood is just coming to an end, and out of that vast circle, happy and gay, a path takes shape.” But another teenager, Anne Frank, writing in her diary while hiding from the Nazis, described tumultuous teen emotions:

My treatment varies so much. One day Anne is so sensible and is allowed to know everything; and the next day I hear that Anne is just a silly little goat who doesn’t know anything at all and imagines that she’s learned a wonderful lot from books…. Oh, so many things bubble up inside me as I lie in bed, having to put up with people I’m fed up with, who always misinterpret my intentions.

G. Stanley Hall (1904), one of the first psychologists to describe adolescence, believed that this tension between biological maturity and social dependence creates a period of “storm and stress.” Indeed, after age 30, many who grow up in independence-

But for many, adolescence is a time of vitality without the cares of adulthood, a time of rewarding friendships, heightened idealism, and a growing sense of life’s exciting possibilities.

Physical Development

puberty the period of sexual maturation, during which a person becomes capable of reproducing.

Adolescence begins with puberty, the time when we mature sexually. Puberty follows a surge of hormones, which may intensify moods and which trigger the bodily changes discussed in Chapter 4.

Earlyversus late maturing. Just as in the earlier life stages, the sequence of physical changes in puberty (for example, breast buds and visible pubic hair before menarche—the first menstrual period) is far more predictable than their timing. Some girls start their growth spurt at 9, some boys as late as age 16. Though such variations have little effect on height at maturity, they may have psychological consequences. It is not only when we mature that counts, but how people react to our physical development.

For boys, early maturation has mixed effects. Boys who are stronger and more athletic during their early teen years tend to be more popular, self-

Girls in various countries are developing breasts and reaching puberty earlier today than in the past, a phenomenon variously attributed to increased body fat, increased hormone-

The teenage brain. An adolescent’s brain is also a work in progress. Until puberty, brain cells increase their connections, like trees growing more roots and branches. Then, during adolescence, comes a selective pruning of unused neurons and connections (Blakemore, 2008). What we don’t use, we lose. It’s rather like traffic engineers reducing congestion by eliminating certain streets and constructing new beltways that move traffic more efficiently.

205

Compared with adults, teens listen more to music and prefer more intense music (Bonneville-

As teens mature, their frontal lobes also continue to develop. The growth of myelin, the fatty tissue that forms around axons and speeds neurotransmission, enables better communication with other brain regions (Kuhn, 2006; Silveri et al., 2006). These developments bring improved judgment, impulse control, and long-

Frontal lobe maturation nevertheless lags behind that of the emotional limbic system. Puberty’s hormonal surge and limbic system development help explain teens’ occasional impulsiveness, risky behaviors, and emotional storms—

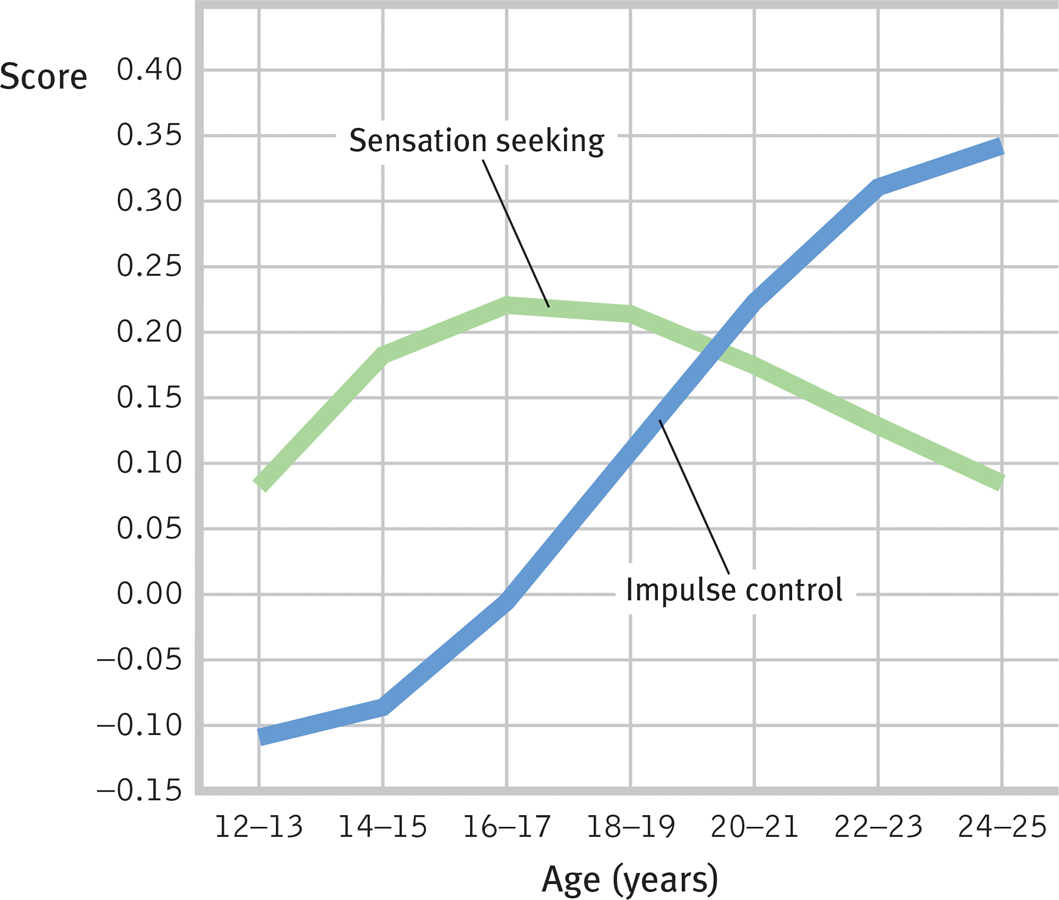

Figure 5.18

Figure 5.18Impulse control lags reward seeking National surveys of more than 7000 American 12-

So, when Junior drives recklessly and academically self-

In 2004, the American Psychological Association (APA) joined seven other medical and mental health associations in filing U.S. Supreme Court briefs, arguing against the death penalty for 16-

Question

abAvh19cq4yEAuB+3PZMqQpgi8jwxtYEYpBEnPWq16ZKHV77qZSW71QQUh+4AWm6lKbIKl38gYKP1BRu569AzxZPn6MSNhTViSXpsN0y5uKMKehYI5r8cQAtO6+M/F4z8nVBtot7XYzKfGZOkpM4jxXUdosbbiUGzlhuyKIU06XWOAHx++kpp/rMfSWH3Hw3417/NFIni0a07aq+sbSwRwDxi1cjRskws2CT1br+Dx8gi4gbJAJYDoLD9bkcD801xjEN3GxmdvOGCj54Cognitive Development

5-

“When the pilot told us to brace and grab our ankles, the first thing that went through my mind was that we must all look pretty stupid.”

Jeremiah Rawlings, age 12, after a 1989 DC-

During the early teen years, reasoning is often self-

206

Developing Reasoning Power

When adolescents achieve the intellectual summit that Jean Piaget called formal operations, they apply their new abstract reasoning tools to the world around them. They may think about what is ideally possible and compare that with the imperfect reality of their society, their parents, and themselves. They may debate human nature, good and evil, truth and justice. Their sense of what’s fair changes from simple equality to equity—

Developing Morality

Two crucial tasks of childhood and adolescence are discerning right from wrong and developing character—

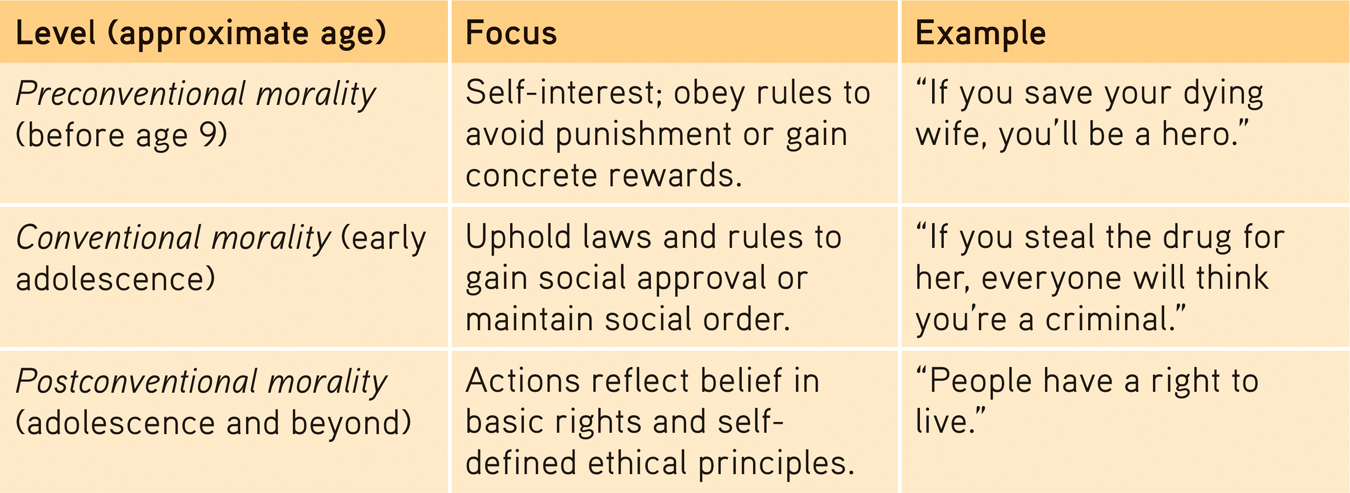

Moral Reasoning Piaget (1932) believed that children’s moral judgments build on their cognitive development. Agreeing with Piaget, Lawrence Kohlberg (1981, 1984) sought to describe the development of moral reasoning, the thinking that occurs as we consider right and wrong. Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas (for example, whether a person should steal medicine to save a loved one’s life) and asked children, adolescents, and adults whether the action was right or wrong. His analysis of their answers led him to propose three basic levels of moral thinking: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional (TABLE 5.3). Kohlberg claimed these levels form a moral ladder. As with all stage theories, the sequence is unvarying. We begin on the bottom rung. Preschoolers, typically identifying with their cultural group, conform to and enforce its moral norms (Schmidt & Tomasello, 2012). Later, we ascend to varying heights. Kohlberg’s critics have noted that his postconventional stage is culturally limited, appearing mostly among people who prize individualism (Eckensberger, 1994; Miller & Bersoff, 1995).

Table 5.3

Table 5.3Kohlberg’s Levels of Moral Thinking

Moral Intuition Psychologist Jonathan Haidt (2002, 2012) believes that much of our morality is rooted in moral intuitions—“quick gut feelings, or affectively laden intuitions.” According to this intuitionist view, the mind makes moral judgments as it makes aesthetic judgments—

207

One woman recalled driving through her snowy neighborhood with three young men as they passed “an elderly woman with a shovel in her driveway. I did not think much of it, when one of the guys in the back asked the driver to let him off there…. When I saw him jump out of the back seat and approach the lady, my mouth dropped in shock as I realized that he was offering to shovel her walk for her.” Witnessing this unexpected goodness triggered elevation: “I felt like jumping out of the car and hugging this guy. I felt like singing and running, or skipping and laughing. I felt like saying nice things about people” (Haidt, 2000).

“Could human morality really be run by the moral emotions,” Haidt wonders, “while moral reasoning struts about pretending to be in control?” Consider the desire to punish. Laboratory games reveal that the desire to punish wrongdoings is mostly driven not by reason (such as an objective calculation that punishment deters crime) but rather by emotional reactions, such as moral outrage (Darley, 2009). After the emotional fact, moral reasoning—

This intuitionist perspective on morality finds support in a study of moral paradoxes. Imagine seeing a runaway trolley headed for five people. All will certainly be killed unless you throw a switch that diverts the trolley onto another track, where it will kill one person. Should you throw the switch? Most say Yes. Kill one, save five.

Now imagine the same dilemma, except that your opportunity to save the five requires you to push a large stranger onto the tracks, where he will die as his body stops the trolley. The logic is the same—

While the new research illustrates the many ways moral intuitions trump moral reasoning, other research reaffirms the importance of moral reasoning. The religious and moral reasoning of the Amish, for example, shapes their practices of forgiveness, communal life, and modesty (Narvaez, 2010). Joshua Greene (2010) likens our moral cognition to a camera. Usually, we rely on the automatic point-

208

Moral Action Our moral thinking and feeling surely affect our moral talk. But sometimes talk is cheap and emotions are fleeting. Morality involves doing the right thing, and what we do also depends on social influences. As political theorist Hannah Arendt (1963) observed, many Nazi concentration camp guards during World War II were ordinary “moral” people who were corrupted by a powerfully evil situation.

Today’s character education programs tend to focus on the whole moral package—

“It is a delightful harmony when doing and saying go together.”

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–1592)

A big part of moral development is the self-

Our capacity to delay gratification—to pass on small rewards now for bigger rewards later—

Question

DrINyJX6lqDEtfpPohM9PquHP5xeRvJrhVMNJLYXUZL1sEJd5oRQpbkCjG60FnKqAwR8EACDnD/6NUGxYFtBcY3RSwIYriy8zatoJi65Vc1M0ev8YMJ6uiL/rGnBHYP2HWElzPfoXlh7QnzLa2Xv6D+YlRVrSq9crPwRViPY+QrwDpZvOOM3mOd/dYTXj9/qJM1S/qcEZlVSnc2vDuKWNbRwhH8PT9KusVLFBFMboHYbL5k0DT3QhsQJBXheqN/tbty6YMfCLSnRHOoUdrKb+9PKeU95QSnJoyt2tQyIewt/+IeHGHLw7g==RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- According to Kohlberg, ______________ morality focuses on self-

interest, ______________ morality focuses on self- defined ethical principles, and ______________ morality focuses on upholding laws and social rules.

preconventional; postconventional; conventional

Social Development

5-

“Somewhere between the ages of 10 and 13 (depending on how hormone-

Jon Stewart et al., Earth (The Book), 2010

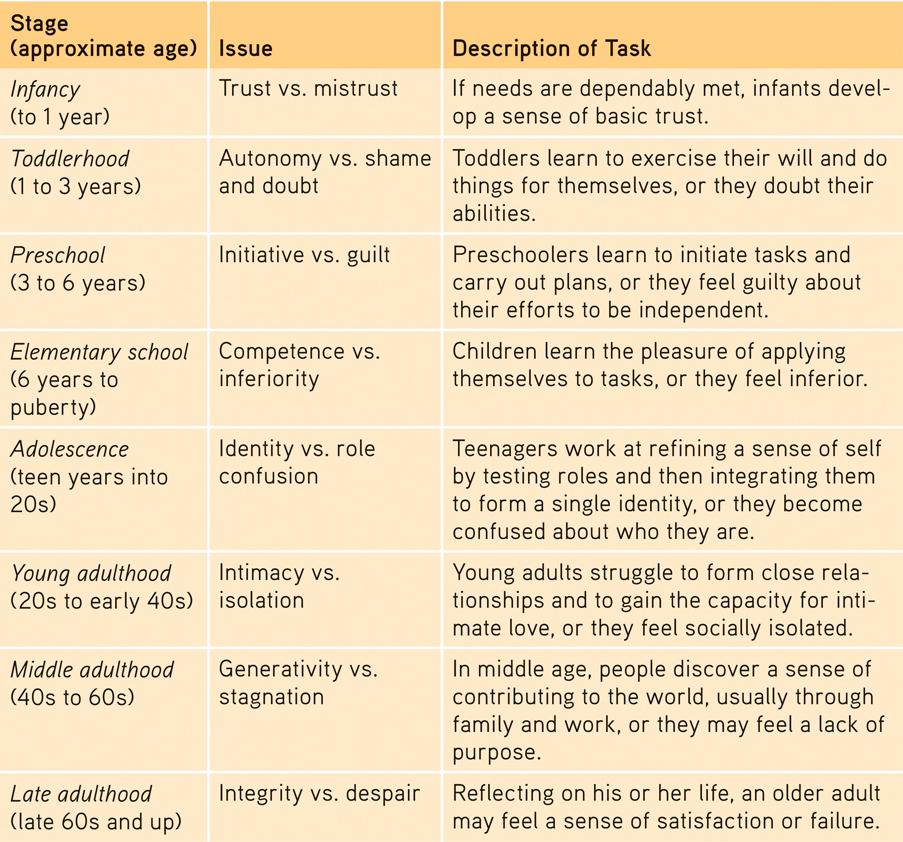

Theorist Erik Erikson (1963) contended that each stage of life has its own psychosocial task, a crisis that needs resolution. Young children wrestle with issues of trust, then autonomy (independence), then initiative. School-

Table 5.4

Table 5.4Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

As sometimes happens in psychology, Erikson’s interests were bred by his own life experience. As the son of a Jewish mother and a Danish Gentile father, Erikson was “doubly an outsider,” reported Morton Hunt (1993, p. 391). He was “scorned as a Jew in school but mocked as a Gentile in the synagogue because of his blond hair and blue eyes.” Such episodes fueled his interest in the adolescent struggle for identity.

209

Forming an Identity

“Self-

C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain, 1940

identity our sense of self; according to Erikson, the adolescent’s task is to solidify a sense of self by testing and integrating various roles.

social identity the “we” aspect of our self-

To refine their sense of identity, adolescents in individualist cultures usually try out different “selves” in different situations. They may act out one self at home, another with friends, and still another at school or online. If two situations overlap—

For both adolescents and adults, group identities are often formed by how we differ from those around us. When living in Britain, I [DM] become conscious of my Americanness. When spending time with my daughter in Africa, I become conscious of my minority White race. When surrounded by women, I am mindful of my gender identity. For international students, for those of a minority ethnic group or sexual orientation, or for people with a disability, a social identity often forms around their distinctiveness.

Erikson noticed that some adolescents forge their identity early, simply by adopting their parents’ values and expectations. (Traditional, less individualist cultures teach adolescents who they are, rather than encouraging them to decide on their own.) Other adolescents may adopt the identity of a particular peer group—

For an interactive self-

For an interactive self-

Most young people develop a sense of contentment with their lives. A question: Which statement best describes you? “I would choose my life the way it is right now” or, “I wish I were somebody else”? When American teens answered, 81 percent picked the first, and 19 percent the second (Lyons, 2004). Reflecting on their existence, 75 percent of American collegians say they “discuss religion/spirituality” with friends, “pray,” and agree that “we are all spiritual beings” and “search for meaning/purpose in life” (Astin et al., 2004; Bryant & Astin, 2008). This would not surprise Stanford psychologist William Damon and his colleagues (2003), who have contended that a key task of adolescence is to achieve a purpose—

210

intimacy in Erikson’s theory, the ability to form close, loving relationships; a primary developmental task in young adulthood.

Several nationwide studies indicate that young Americans’ self-

These are the years when many people in industrialized countries begin exploring new opportunities by attending college or working full time. Many college seniors have achieved a clearer identity and a more positive self-

Erikson contended that adolescent identity formation (which continues into adulthood) is followed in young adulthood by a developing capacity for intimacy, the ability to form emotionally close relationships. Romantic relationships, which tend to be emotionally intense, are reported by some two in three North American 17-

Parent and Peer Relationships

5-

As adolescents in Western cultures seek to form their own identities, they begin to pull away from their parents (Shanahan et al., 2007). The preschooler who can’t be close enough to her mother, who loves to touch and cling to her, becomes the 14-

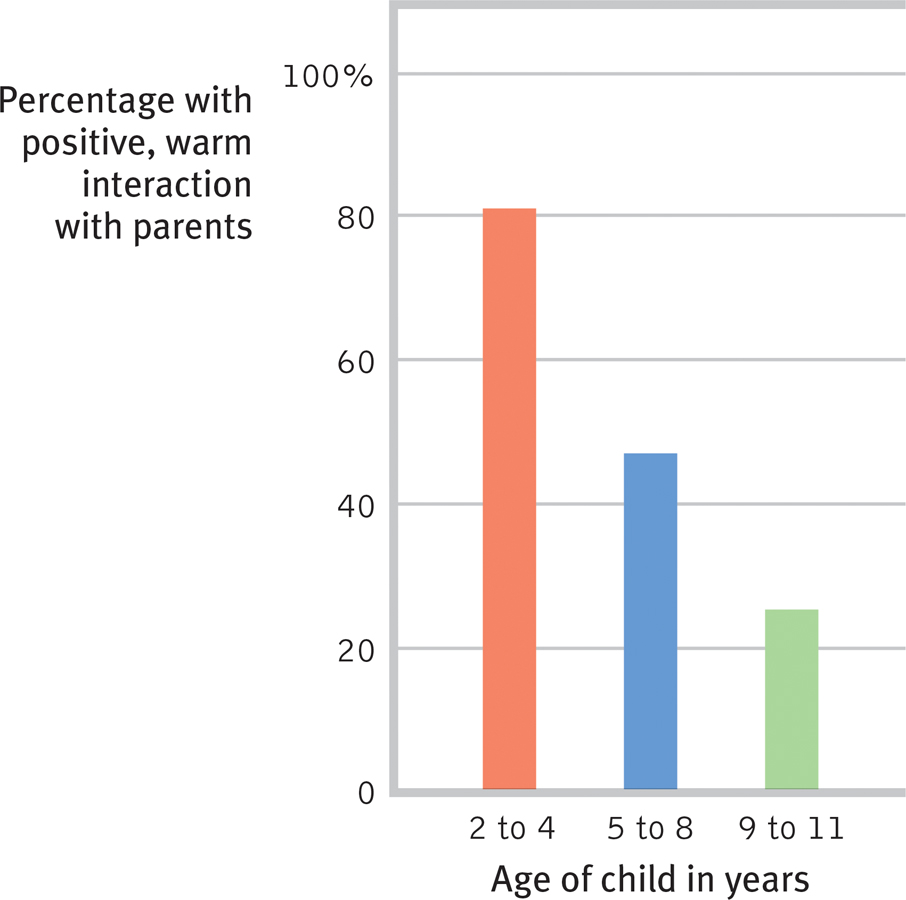

Figure 5.19

Figure 5.19The changing parent-

For a minority of parents and their adolescents, differences lead to real splits and great stress (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). But most disagreements are at the level of harmless bickering. With sons, the issues often are behavior problems, such as acting out or hygiene, while for daughters, the issues commonly involve relationships, such as dating and friendships (Schlomer et al., 2011). Most adolescents—

“I love u guys.”

Emily Keyes’ final text message to her parents before dying in a Colorado school shooting, 2006

211

Positive parent-

Adolescence is typically a time of diminishing parental influence and growing peer influence. Asked in a survey if they had “ever had a serious talk” with their child about illegal drugs, 85 percent of American parents answered Yes. But if the parents had indeed given this earnest advice, many teens had apparently tuned it out: Only 45 percent could recall such a talk (Morin & Brossard, 1997).

As we noted in Chapter 4, heredity does much of the heavy lifting in forming individual temperament and personality differences, and peer influences do much of the rest. When with peers, teens discount the future and focus more on immediate rewards (O’Brien et al., 2011). Most teens are herd animals. They talk, dress, and act more like their peers than their parents. What their friends are, they often become, and what “everybody’s doing,” they often do.

Part of what everybody’s doing is networking—

Both online and in real life, for those who feel excluded by their peers, the pain is acute. “The social atmosphere in most high schools is poisonously clique-

Teens have tended to see their parents as having more influence in other areas—

Question

UjvE/0lqezXVPr/Q/N2jC7Tped5XoEypM65sd0lDOmyoeOrhcJPyB2NbwrZA3+xKXQq2JxFUoKxT9Fh7QqQoZ+a1Es0djoYnVnJSTPHKi6X4CtdfhM59ru/FfgiG1FOm0Yin7WEnZMqp4Qik1AJdzOvfxYH3YIkscjXU72G60geme4r6WWIyl4JF93sqZLgwJa8Irsceg/Qhob6KZQmRee78pojyPwaHpRgUWGlLNvcIAqsCRnGn1A8/qSDDr98X9BUM1HZOjO7zwntW212

Emerging Adulthood

5-

In the Western world, adolescence now roughly corresponds to the teen years. At earlier times, and in other parts of the world today, this slice of life has been much smaller (Baumeister & Tice, 1986). Shortly after sexual maturity, young people would assume adult responsibilities and status. The event might be celebrated with an elaborate initiation—

When schooling became compulsory in many Western countries, independence was put on hold until after graduation. From Europe to Australia, adolescents now take more time to establish themselves as adults. In the United States, for example, the average age at first marriage has increased more than 5 years since 1960, to 29 for men, and 27 for women. In 1960, three in four women and two in three men had, by age 30, finished school, left home, become financially independent, married, and had a child. Today, fewer than half of 30-

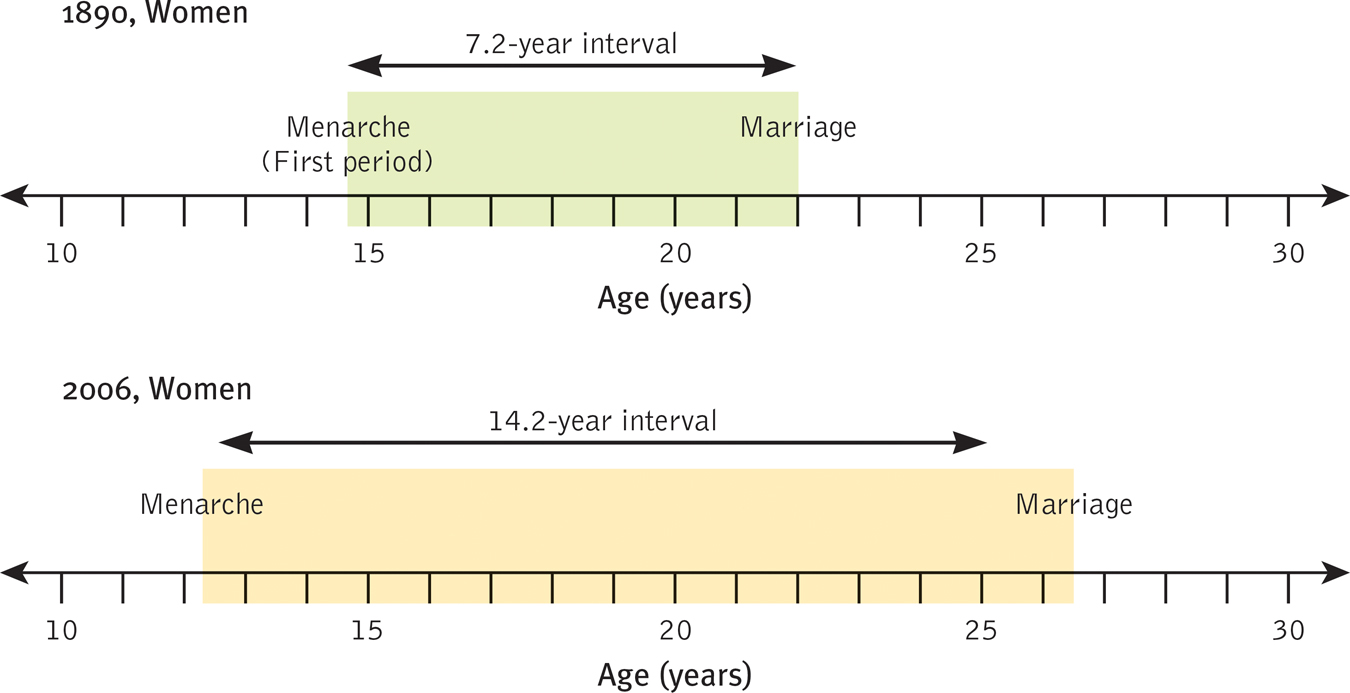

Together, later independence and earlier sexual maturity have widened the once-

Figure 5.20

Figure 5.20The transition to adulthood is being stretched from both ends In the 1890s, the average interval between a woman’s first menstrual period and marriage, which typically marked a transition to adulthood, was about 7 years; a century later in industrialized countries it was about 14 years (Finer & Philbin, 2014; Guttmacher, 1994). Although many adults are unmarried, later marriage combines with prolonged education and earlier menarche to help stretch out the transition to adulthood.

emerging adulthood a period from about age 18 to the mid-

213

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Match the psychosocial development stage below (1–8) with the issue that Erikson believed we wrestle with at that stage (a–h).

|

1. Infancy 2. Toddlerhood 3. Preschool |

4. Elementary school 5. Adolescence 6. Young adulthood |

7. Middle adulthood 8. Late adulthood |

|

a. Generativity vs. stagnation b. Integrity vs. despair c. Initiative vs. guilt d. Intimacy vs. isolation |

e. Identity vs. role confusion f. Competence vs. inferiority g. Trust vs. mistrust h. Autonomy vs. shame and doubt |

1. g, 2. h, 3. c, 4. f,

5. e, 6. d, 7. a, 8. b