5.4 Adulthood

How old does a person have to be before you think of him or her as old? Depends on who you ask. For 18-

“I am still learning.”

Michelangelo, 1560, at age 85

The unfolding of people’s adult lives continues acoss the life span. It is, however, more difficult to generalize about adulthood stages than about life’s early years. If you know that James is a 1-

214

Physical Development

5-

Like the declining daylight after the summer solstice, our physical abilities—

menopause the time of natural cessation of menstruation; also refers to the biological changes a woman experiences as her ability to reproduce declines.

Physical Changes in Middle Adulthood

Post-

Aging also brings a gradual decline in fertility, especially for women. For a 35-

With age, sexual activity lessens. Nearly 9 in 10 Americans in their late twenties reported having had vaginal intercourse in the past year, compared with 22 percent of women and 43 percent of men who were over 70 (Herbenick et al., 2010; Reece et al., 2010). Nevertheless, most men and women remain capable of satisfying sexual activity, and most express satisfaction with their sex life. This was true of 70 percent of Canadians surveyed (ages 40 to 64) and 75 percent of Finns (ages 65 to 74) (Kontula & Haavio-

Physical Changes in Late Adulthood

Is old age “more to be feared than death” (Juvenal, Satires)? Or is life “most delightful when it is on the downward slope” (Seneca, Epistulae ad Lucilium)? What is it like to grow old?

“I intend to live forever—

Comedian Steven Wright

Life Expectancy From 1950 to 2011, life expectancy at birth increased worldwide from 46.5 years to 70 years—

215

Throughout the life span, males are more prone to dying. Although 126 male embryos begin life for every 100 females, the sex ratio is down to 105 males for every 100 females at birth (Strickland, 1992). During the first year, male infants’ death rates exceed females’ by one-

But few of us live to 100. Disease strikes. The body ages. Its cells stop reproducing. It becomes frail and vulnerable to tiny insults—

Low stress and good health habits enable longevity, as does a positive spirit. Chronic anger and depression increase our risk of premature death. Researchers have even observed an intriguing death-

Sensory Abilities, Strength, and Stamina Although physical decline begins in early adulthood, we are not usually acutely aware of it until later life, when the stairs get steeper, the print gets smaller, and other people seem to mumble more. Visual sharpness diminishes, and distance perception and adaptation to light-

“For some reason, possibly to save ink, the restaurants had started printing their menus in letters the height of bacteria.”

Dave Barry, Dave Barry Turns Fifty, 1998

With age, the eye’s pupil shrinks and its lens becomes less transparent, reducing the amount of light reaching the retina. A 65-

Most stairway falls taken by older people occur on the top step, precisely where the person typically descends from a window-

Health As people age, they care less about what their bodies look like and more about how they function. For those growing older, there is both bad and good news about health. The bad news: The body’s disease-

216

The Aging Brain Up to the teen years, we process information with greater and greater speed (Fry & Hale, 1996; Kail, 1991). But compared with teens and young adults, older people take a bit more time to react, to solve perceptual puzzles, even to remember names (Bashore et al., 1997; Verhaeghen & Salthouse, 1997). The neural processing lag is greatest on complex tasks (Cerella, 1985; Poon, 1987). At video games, most 70-

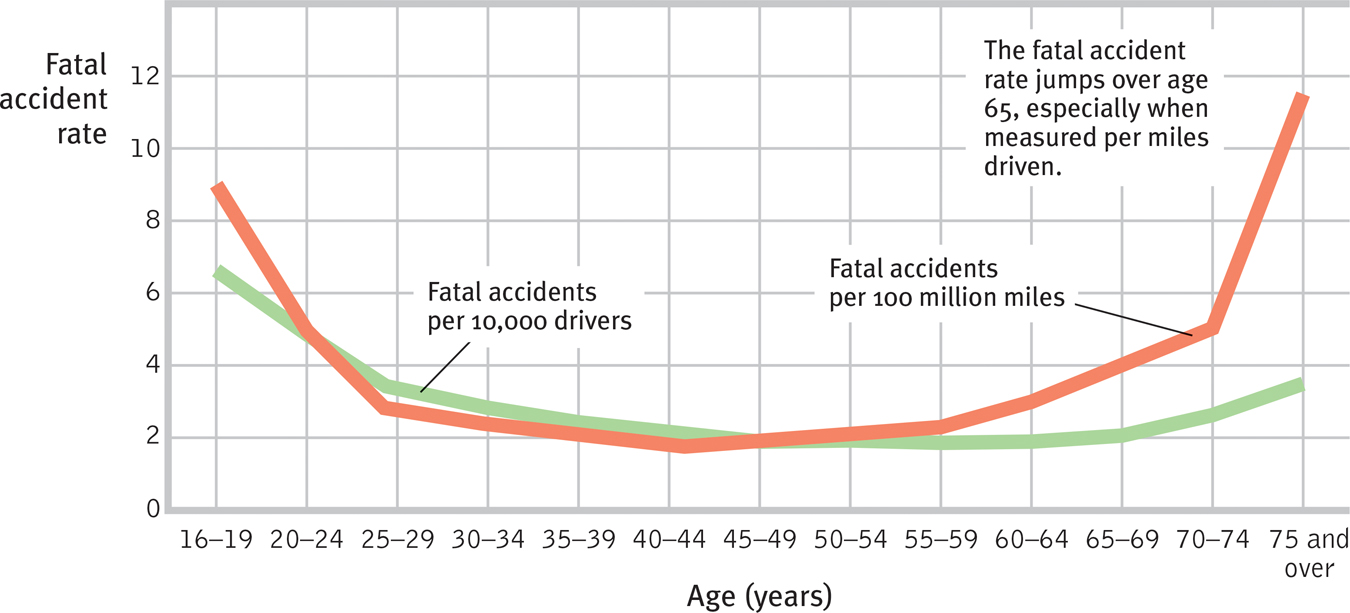

Figure 5.21

Figure 5.21Age and driver fatalities Slowing reactions contribute to increased accident risks among those 75 and older, and their greater fragility increases their risk of death when accidents happen (NHTSA, 2000). Would you favor driver exams based on performance, not age, to screen out those whose slow reactions or sensory impairments indicate accident risk?

Even speech slows (Jacewicz et al. 2009). One research team compared speeches of the renowned psychologist, B. F. Skinner, and observed his speaking rate at ages 58, 73, and 90 as 148, 137, and 106 words per minute, respectively (Epstein, 2012).

Brain regions important to memory begin to atrophy during aging (Schacter, 1996). No wonder older adults, after taking a memory test, feel older: “aging 5 years in 5 minutes,” jested one research report (Hughes et al., 2013). In early adulthood, a small, gradual net loss of brain cells begins, contributing by age 80 to a brain-

EXERCISE AND AGING And more good news: Exercise slows aging. Active older adults tend to be mentally quick older adults. Physical exercise not only enhances muscles, bones, and energy and helps prevent obesity and heart disease, it maintains the telomeres that protect the chromosome ends (Leslie, 2011).

Exercise also stimulates brain cell development and neural connections, thanks perhaps to increased oxygen and nutrient flow (Erickson et al., 2013; Pereira et al., 2007). Sedentary older adults randomly assigned to aerobic exercise programs exhibit enhanced memory, sharpened judgment, and reduced risk of significant cognitive decline (DeFina et al., 2013; Liang et al., 2010; Nagamatsu et al., 2013). In aging brains, exercise reduces brain shrinkage (Gow et al., 2012). It promotes neurogenesis (the birth of new nerve cells) in the hippocampus, a brain region important for memory (Cherkas et al., 2008; Erickson, 2009; Pereira et al., 2007). And it increases the cellular mitochondria that help power both muscles and brain cells (Steiner et al., 2011). We are more likely to rust from disuse than to wear out from overuse. Fit bodies support fit minds.

Question

h62Epv0EeSDX0MpAysTuGwb5C4YmJCvtx0rJPRl6AE6csuC7j6A1255RmlaTxXV9n9PhBvHzqhF9N9q1JWd31nBHebODTLho9ZLOVe5TGNV/spf+owAXoBrKEVNycVeDfMUIor1jM0lGAR8M2FiLLSBpYcVRXyEYAsm+s6Ves0mcX2z3zJSk0Gl6Kv9Vk0v/WbKmek8OqsRflEEcki3xFnd9WkkfzUC3maAb4mK2PpKhIZXrzD4I7wkQhxLWAZfQMPtH8xW4KeI=217

Cognitive Development

Aging and Memory

5-

Among the most intriguing developmental psychology questions is whether adult cognitive abilities, such as memory, intelligence, and creativity, parallel the gradually accelerating decline of physical abilities.

As we age, we remember some things well. Looking back in later life, adults asked to recall the one or two most important events over the last half-

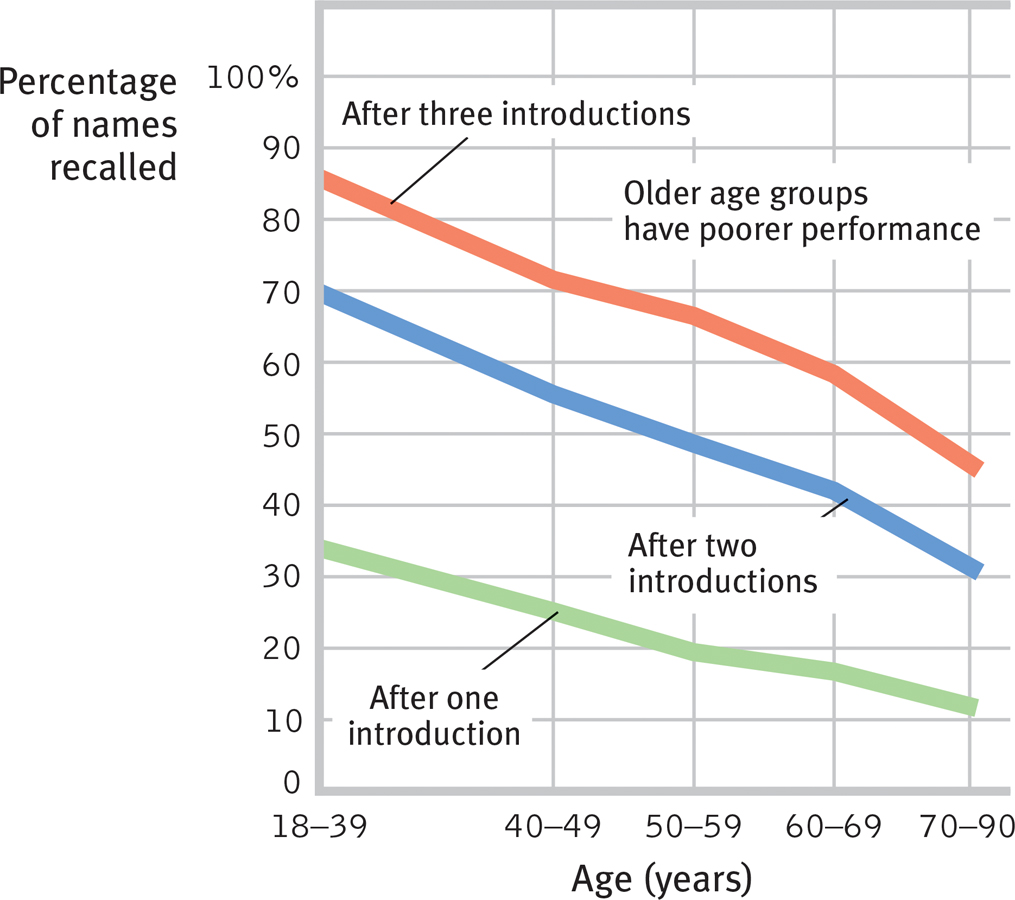

Early adulthood is indeed a peak time for some types of learning and remembering. In one test of recall, people watched video clips as 14 strangers said their names, using a common format: “Hi, I’m Larry” (Crook & West, 1990). Then those strangers reappeared and gave additional details. For example, they said, “I’m from Philadelphia,” providing more visual and voice cues for remembering the person’s name. As FIGURE 5.22 shows, after a second and third replay of the introductions, everyone remembered more names, but younger adults consistently surpassed older adults.

Figure 5.22

Figure 5.22Tests of recall Recalling new names introduced once, twice, or three times is easier for younger adults than for older ones. (Data from Crook & West, 1990.)

Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that nearly two-

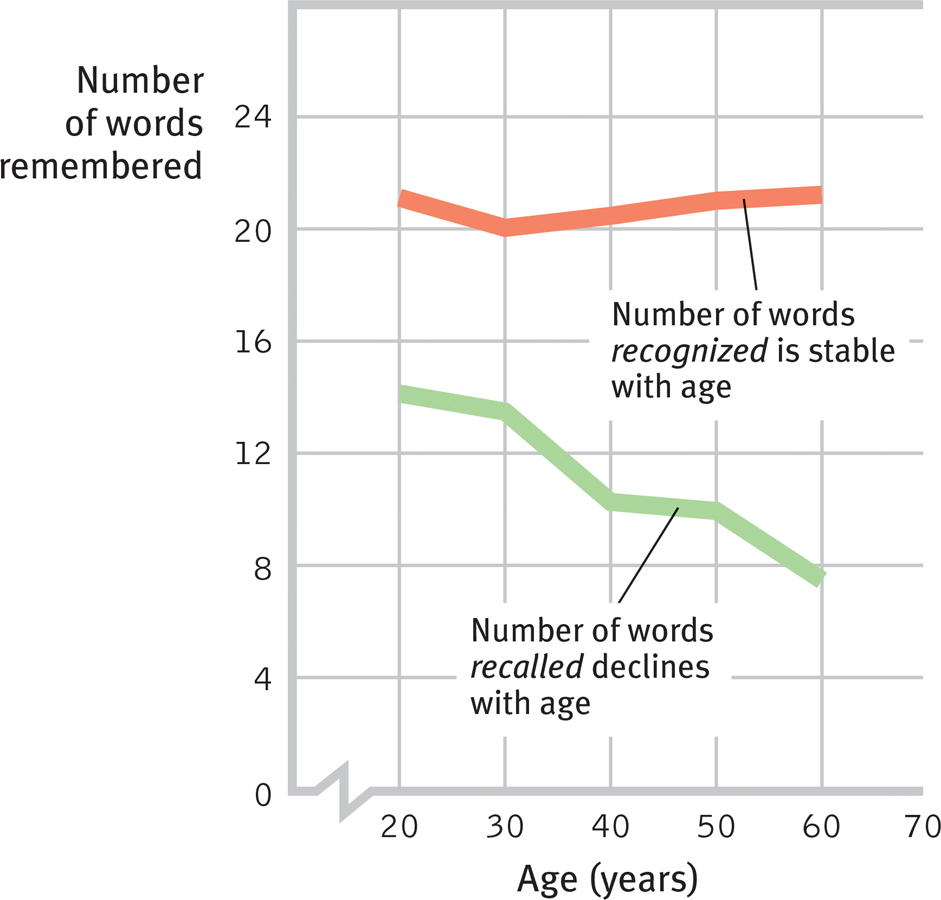

Figure 5.23

Figure 5.23Recall and recognition in adulthood In this experiment, the ability to recall new information declined during early and middle adulthood, but the ability to recognize new information did not. (Data from Schonfield & Robertson, 1966.)

Teens and young adults surpass both young children and 70-

In our capacity to learn and remember, as in other areas of development, we differ. Younger adults vary in their abilities to learn and remember, but 70-

No matter how quick or slow we are, remembering seems also to depend on the type of information we are trying to retrieve. If the information is meaningless—

218

Psychologists who study the aging mind have been debating whether “brain fitness” computer training programs can build mental muscles and stave off cognitive decline. Given what we know about the brain’s plasticity, can exercising our brains on a “cognitive treadmill”—with memory, visual tracking, and problem-

Based on such findings, some computer game makers are marketing daily brain-

If you are within five years of 20, what experiences from the past year will you likely never forget? (This is the time of your life you may best remember when you are 50.)

cross-

longitudinal study research in which the same people are restudied and retested over a long period.

Chapter 10 explores another dimension of cognitive development: intelligence. As we will see, cross-

Neurocognitive Disorders and Alzheimer’s Disease

5-

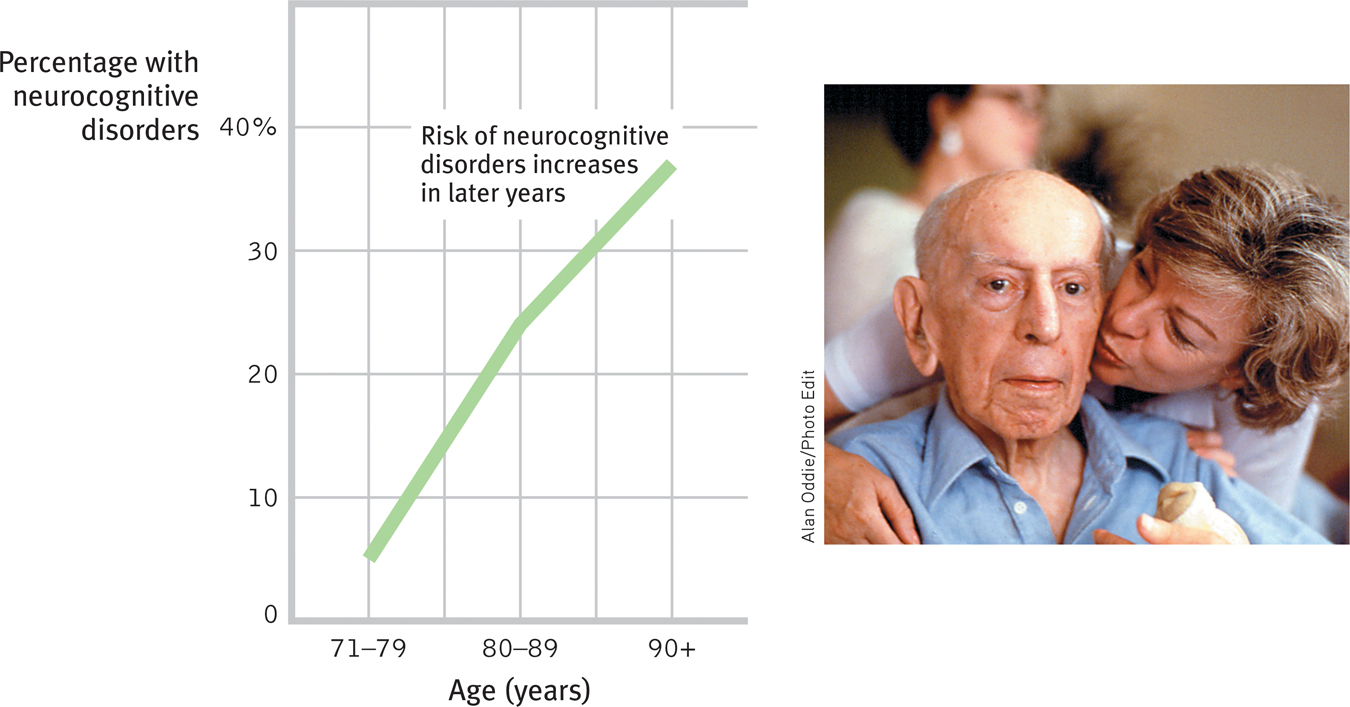

Most people who live into their nineties do so with clear minds. Some, unfortunately, suffer a substantial loss of brain cells in a process that is not normal aging. A series of small strokes, a brain tumor, or alcohol use disorder can progressively damage the brain, causing that mental erosion we call a neurocognitive disorder (NCD, formerly called dementia). Heavy midlife smoking more than doubles later risk of the disorder (Rusanen et al., 2011). The feared brain ailment Alzheimer’s disease strikes 3 percent of the world’s population by age 75. Up to age 95, the incidence of mental disintegration doubles roughly every 5 years (FIGURE 5.24).

Figure 5.24

Figure 5.24Incidence of neurocognitive disorders (NCDs) by age The risk of mental disintegration due to Alzheimer’s disease, strokes, or other brain disease increases with age (Brookmeyer et al., 2011). Still, most people who live into their nineties do so with clear minds.

neurocognitive disorders (NCDs) acquired (not lifelong) disorders marked by cognitive deficits; often related to Alzheimer’s disease, brain injury or disease, or substance abuse. In older adults neurocognitive disorders were formerly called dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease a neurocognitive disorder marked by neural plaques, often with an onset after age 80, and entailing a progressive decline in memory and other cognitive abilities.

Alzheimer’s destroys even the brightest of minds. First memory deteriorates, then reasoning. (Occasionally forgetting where you laid the car keys is no cause for alarm; forgetting how to get home may suggest Alzheimer’s.) Robert Sayre (1979) recalled his father shouting at his afflicted mother to “think harder,” while his mother, confused, embarrassed, on the verge of tears, randomly searched the house for lost objects. As the disease runs its course, after 5 to 20 years, the person becomes emotionally flat, then disoriented and disinhibited, then incontinent, and finally mentally vacant—

“We’re keeping people alive so they can live long enough to get Alzheimer’s disease.”

Steve McConnell, Alzheimer’s Association Vice President, 2007

219

Underlying the symptoms of Alzheimer’s are a loss of brain cells and a deterioration of neurons that produce the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is vital to memory and thinking. An autopsy reveals two telltale abnormalities in these acetylcholine-

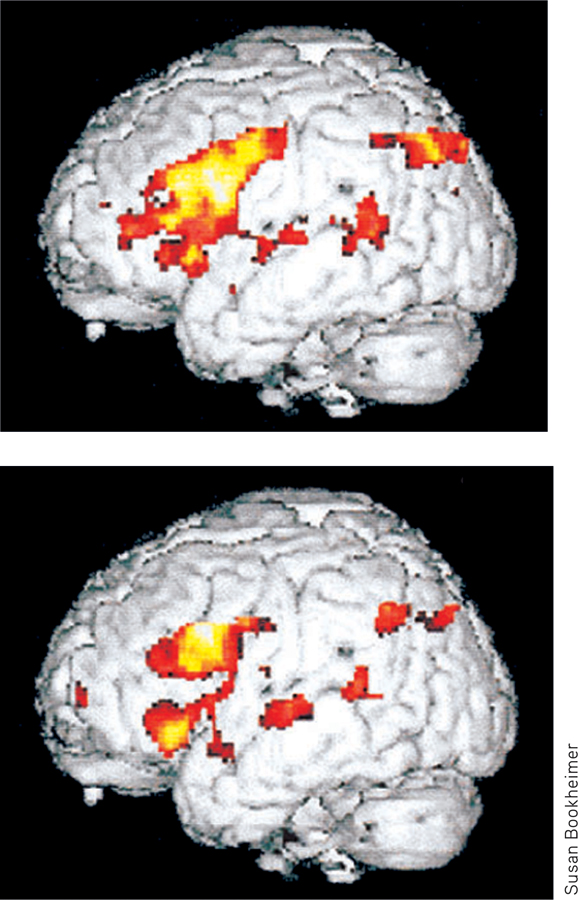

A diminishing sense of smell and slowed or wobbly walking may foretell Alzheimer’s (Belluck, 2012; Wilson et al., 2007). Among older adults, hearing loss, and its associated social isolation, predicts risk of depression and accelerated mental decline (Li et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2011a,b, 2013). Compared with people with good hearing, those with hearing loss show declines in memory, attention, and learning about three years earlier. In people at risk for Alzheimer’s, brain scans (FIGURE 5.25) have also revealed—

Figure 5.25

Figure 5.25Predicting Alzheimer’s disease During a memory test, MRI scans of the brains of people at risk for Alzheimer’s (top) revealed more intense activity (yellow, followed by orange and red) when compared with normal brains (bottom). As brain scans and genetic tests make it possible to identify those likely to suffer Alzheimer’s, would you want to be tested? At what age?

Alzheimer’s is somewhat less common among those who exercise their minds as well as their bodies (Agrigoroaei & Lachman, 2011). As with muscles, so with the brain: Those who use it less often lose it.

Question

lKtBX5L2ewDTl5dJc46BemDutR1jggbVNPC11lqJ3SZ9KKILgVfG4XzUJo2I1CJf5lGUwoABk83Zr545jbTYTTkr4X21qrExfAsDmDOpks0BMdT+pF20k7gTVICqI6zEWtXub1U8v5V9ihzRpnHBn0tmSJZs/mr3tyLi5jMTy92mTRMqqcggsBrXta/JF+jKiXikBKEm8HyiDT6hGisIuBiDRPumyYv0WNGb6lKb1udxYPGv5UmmNzPmaa7ceF0GEV0ggB7SqOPSBDB5SpiANnmyASsUhIA5mm6OhPdpY21gASDV7c0VGCbMufAy6CF916fynk4fAYCiBhq2b+hNp2ng3d344kcaJBqqqeC0tg1mctF7/4LVlPBecM2C05tFrj5E48MuLuQ5gZHxlAs79O/uDKHnn+7YX8lwYQp8i1bLsaoDSocial Development

5-

Many differences between younger and older adults are created by significant life events. A new job means new relationships, new expectations, and new demands. Marriage brings the joy of intimacy and the stress of merging two lives. The three years surrounding the birth of a child bring increased life satisfaction for most parents (Dyrdal & Lucas, 2011). The death of a loved one creates an irreplaceable loss. Do these adult life events shape a sequence of life changes?

220

Adulthood’s Ages and Stages

As people enter their forties, they undergo a transition to middle adulthood, a time when they realize that life will soon be mostly behind instead of ahead of them. Some psychologists have argued that for many the midlife transition is a crisis, a time of great struggle, regret, or even feeling struck down by life. The popular image of the midlife crisis is an early-

For the 1 in 4 adults who report experiencing a life crisis, the trigger is not age, but a major event, such as illness, divorce, or job loss (Lachman, 2004). Some middle-

“The important events of a person’s life are the products of chains of highly improbable occurrences.”

Joseph Traub, “Traub’s Law,” 2003

social clock the culturally preferred timing of social events such as marriage, parenthood, and retirement.

Life events trigger transitions to new life stages at varying ages. The social clock—the definition of “the right time” to leave home, get a job, marry, have children, and retire—

Even chance events can have lasting significance, by deflecting us down one road rather than another. Albert Bandura (1982, 2005) recalls the ironic true story of a book editor who came to one of Bandura’s lectures on the “Psychology of Chance Encounters and Life Paths”—and ended up marrying the woman who happened to sit next to him. The sequence that led to my [DM] authoring this book (which was not my idea) began with my being seated near, and getting to know, a distinguished colleague at an international conference. Chance events can change our lives.

Adulthood’s Commitments

Two basic aspects of our lives dominate adulthood. Erik Erikson called them intimacy (forming close relationships) and generativity (being productive and supporting future generations). Researchers have chosen various terms—

Love We typically flirt, fall in love, and commit—

Adult bonds of love are most satisfying and enduring when marked by a similarity of interests and values, a sharing of emotional and material support, and intimate self-

221

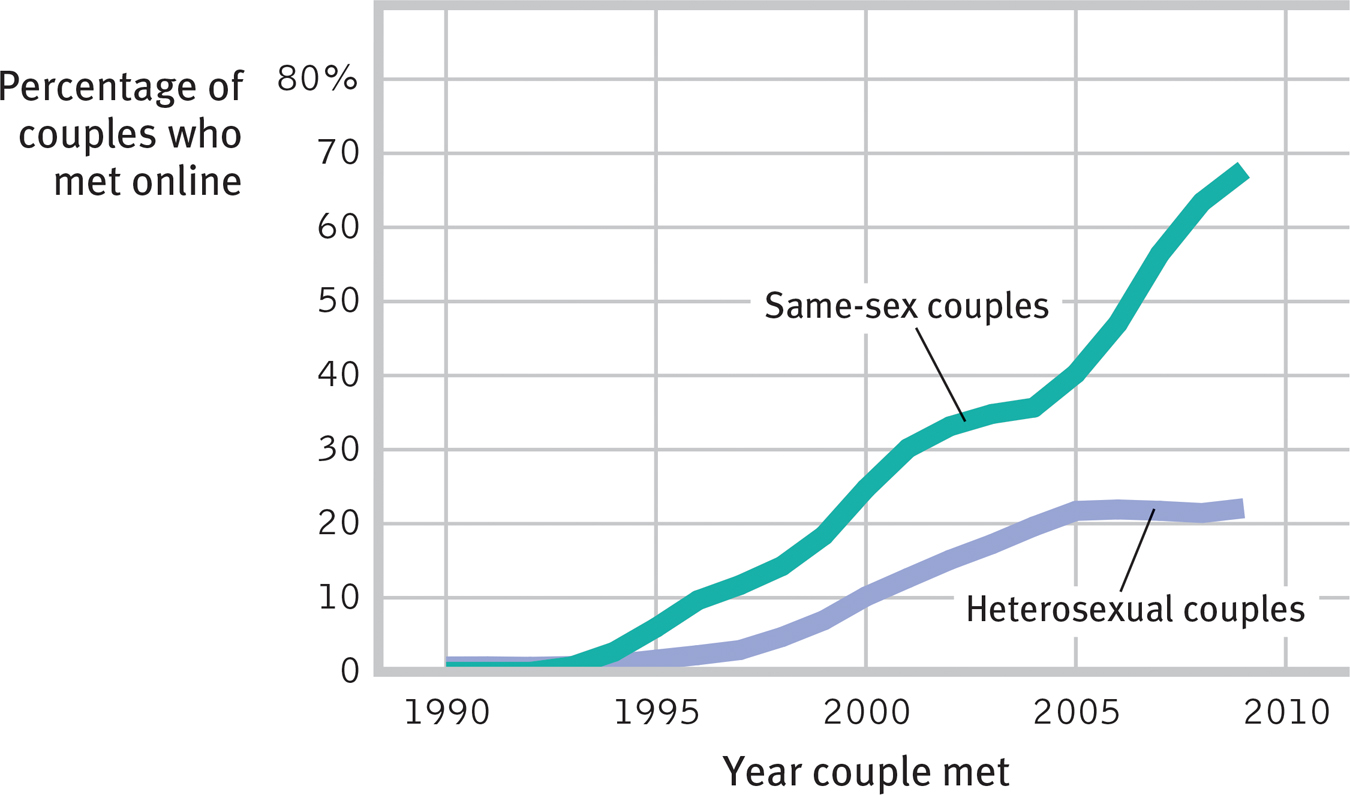

Historically, couples have met at school, on the job, through family, or, especially, through friends. Since the advent of the Internet, such matchmaking has been supplemented by a striking rise in couples who meet online—

Figure 5.26

Figure 5.26The changing way Americans meet their partners A national survey of 2452 straight couples and 462 gay and lesbian couples reveals the increasing role of the Internet. (Data from Rosenfeld, 2013; Rosenfeld & Thomas, 2012.)

Might test-

Although there is more variety in relationships today, the institution of marriage endures. In Western countries, people marry for love. What counts as a “very important” reason to marry? Among Americans, 31 percent say financial stability, and 93 percent say love (Cohn, 2013). And marriage is a predictor of happiness, sexual satisfaction, income, and physical and mental health (Scott et al., 2010). National Opinion Research Center surveys of more than 50,000 Americans since 1972 reveal that 40 percent of married adults, though only 23 percent of unmarried adults, have reported being “very happy.” Lesbian couples, too, have reported greater well-

What do you think? Does marriage correlate with happiness because marital support and intimacy breed happiness, because happy people more often marry and stay married, or both?

222

Relationships that last are not always devoid of conflict. Some couples fight but also shower each other with affection. Other couples never raise their voices yet also seldom praise each other or nuzzle. Both styles can last. After observing the interactions of 2000 couples, John Gottman (1994) reported one indicator of marital success: at least a five-

“Our love for children is so unlike any other human emotion. I fell in love with my babies so quickly and profoundly, almost completely independently of their particular qualities. And yet 20 years later I was (more or less) happy to see them go—

Developmental psychologist Alison Gopnik, “The Supreme Infant,” 2010

Often, love bears children. For most people, this most enduring of life changes is a happy event—

When children begin to absorb time, money, and emotional energy, satisfaction with the relationship itself may decline (Doss et al., 2009). This is especially likely among employed women who, more than they expected, may carry the traditional burden of doing the chores at home. Putting effort into creating an equitable relationship can thus pay double dividends: greater satisfaction, which breeds better parent–child relations (Erel & Burman, 1995).

“To understand your parents’ love, bear your own children.”

Chinese proverb

Although love bears children, children eventually leave home. This departure is a significant and sometimes difficult event. For most people, however, an empty nest is a happy place (Adelmann et al., 1989; Gorchoff et al., 2008). Many parents experience a “postlaunch honeymoon,” especially if they maintain close relationships with their children (White & Edwards, 1990). As Daniel Gilbert (2006) has said, “The only known symptom of ‘empty nest syndrome’ is increased smiling.”

Work For many adults, the answer to “Who are you?” depends a great deal on the answer to “What do you do?” For women and men, choosing a career path is difficult, especially during bad economic times. Even in the best of times, few students in their first two years of college or university can predict their later careers.

For more on work, including discovering your own strengths, see Appendix A: Psychology at Work.

In the end, happiness is about having work that fits your interests and provides you with a sense of competence and accomplishment. It is having a close, supportive companion who cheers your accomplishments (Gable et al., 2006). And for some, it includes having children who love you and whom you love and feel proud of.

223

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Freud defined the healthy adult as one who is able to ______________ and to ______________.

love; work

Well-

5-

To live is to grow older. This moment marks the oldest you have ever been and the youngest you will henceforth be. That means we all can look back with satisfaction or regret, and forward with hope or dread. When asked what they would have done differently if they could relive their lives, people’s most common answer has been “taken my education more seriously and worked harder at it” (Kinnier & Metha, 1989; Roese & Summerville, 2005). Other regrets—

“When you were born, you cried and the world rejoiced. Live your life in a manner so that when you die the world cries and you rejoice.”

Native American proverb

From the teens to midlife, people typically experience a strengthening sense of identity, confidence, and self-

“Hope I die before I get old.”

Pete Townshend, of the Who (written at age 20)

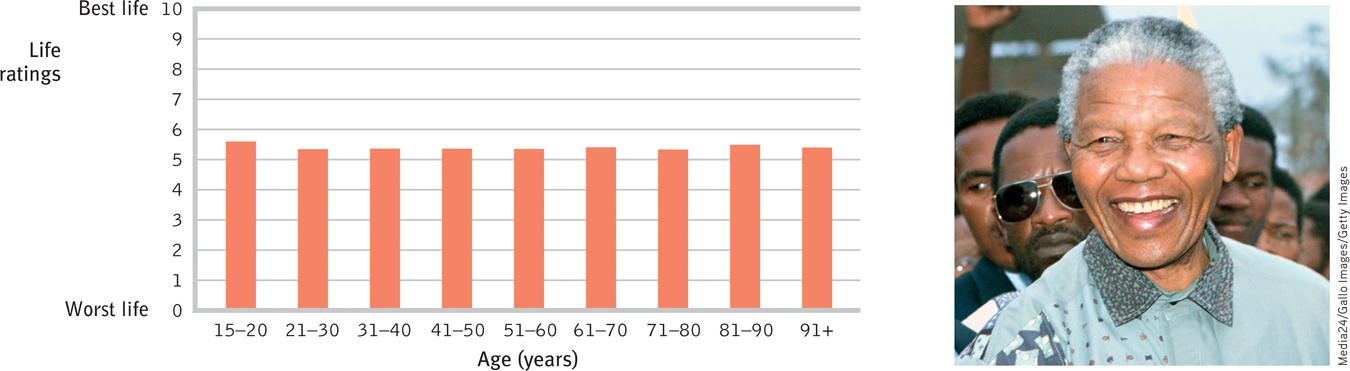

Small wonder that most presume that happiness declines in later life (Lacey et al., 2006). But worldwide, as Gallup researchers discovered, most find that the over-

Figure 5.27

Figure 5.27Nelson Mandela embodied stable life satisfaction The Gallup Organization asked 658,038 people worldwide to rate their lives on a ladder from 0 (“the worst possible life”) to 10 (“the best possible life”). Age gave no clue to life satisfaction. (Data from Morrison et al., 2014.)

“Still married after all these years?

No mystery.

We are each other’s habit, And each other’s history.”

Judith Viorst, “The Secret of Staying Married,” 2007

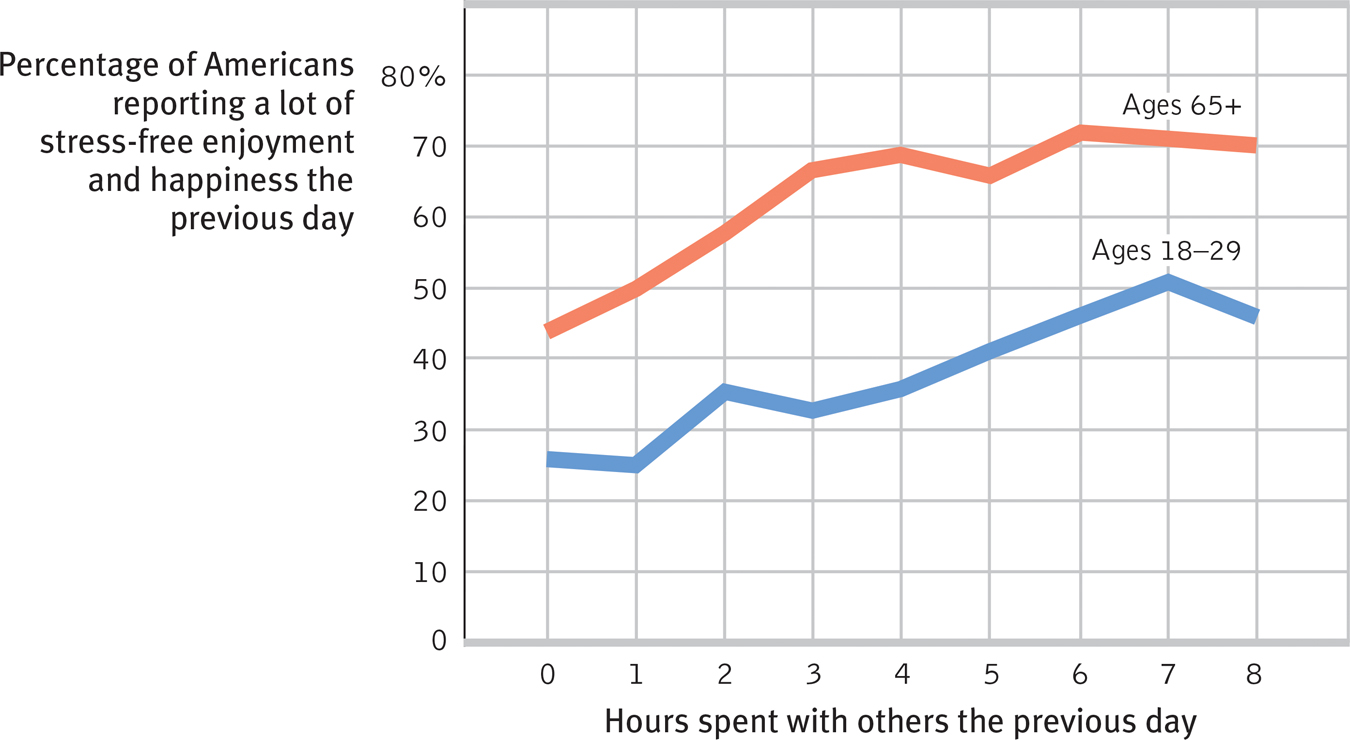

Compared with teens and young adults, older adults also have a smaller social network, with fewer friendships (Wrzus et al., 2012). Like people of all ages, older adults are, however, happiest when not alone (FIGURE 5.28 below). They also experience fewer problems in their relationships—

Figure 5.28

Figure 5.28Humans are social creatures Both younger and older adults report greater happiness when spending time with others. (Note, this correlation could also reflect happier people being more social.) (Gallup survey data reported by Crabtree, 2011.)

224

The aging brain may help nurture these positive feelings. Brain scans of older adults show that the amygdala, a neural processing center for emotions, responds less actively to negative events (but not to positive events) (Mather et al., 2004). Brain-

“At 20 we worry about what others think of us. At 40 we don’t care what others think of us. At 60 we discover they haven’t been thinking about us at all.”

Anonymous

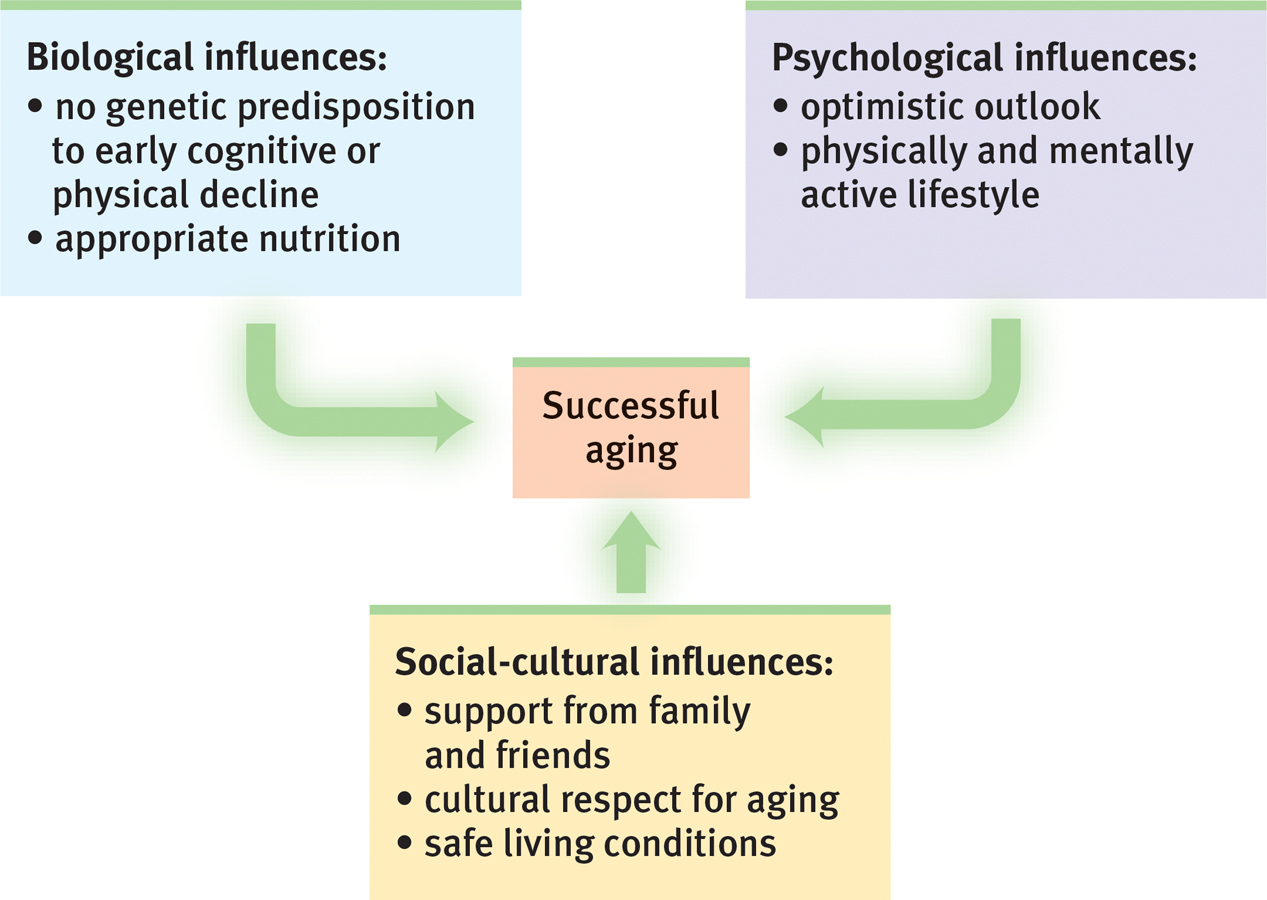

Moreover, at all ages, the bad feelings we associate with negative events fade faster than do the good feelings we associate with positive events (Walker et al., 2003). This contributes to most older people’s sense that life, on balance, has been mostly good. Given that growing older is an outcome of living (an outcome most prefer to early dying), the positivity of later life is comforting. Thanks to biological, psychological, and social-

Figure 5.29

Figure 5.29Biopsychosocial influences on successful aging

The resilience of well-

“The best thing about being 100 is no peer pressure.”

Lewis W. Kuester, 2005, on turning 100

225

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are some of the most significant challenges and rewards of growing old?

Challenges: decline of muscular strength, reaction times, stamina, sensory keenness, cardiac output, and immune system functioning. Risk of cognitive decline increases. Rewards: positive feelings tend to grow, negative emotions are less intense, and anger, stress, worry, and social-

Death and Dying

5-

Warning: If you begin reading the next paragraph, you will die.

“Love—

Brian Moore, The Luck of Ginger Coffey, 1960

But of course, if you hadn’t read this, you would still die in due time. “Time is a great teacher,” noted the nineteenth-

Most of us will also suffer and cope with the deaths of relatives and friends. Usually, the most difficult separation is from one’s partner—

For some, however, the loss is unbearable. One Danish long-

Even so, reactions to a loved one’s death range more widely than most suppose. Some cultures encourage public weeping and wailing; others hide grief. Within any culture, individuals differ. Given similar losses, some people grieve hard and long, others less so (Ott et al., 2007). Contrary to popular misconceptions, however,

- terminally ill and bereaved people do not go through identical predictable stages, such as denial before anger (Friedman & James, 2008; Nolen-

Hoeksema & Larson, 1999). - those who express the strongest grief immediately do not purge their grief more quickly (Bonanno & Kaltman, 1999; Wortman & Silver, 1989). On the other hand, grieving parents who try to protect their partner by “staying strong” and not discussing their child’s death may actually prolong the grieving (Stroebe et al., 2013).

- bereavement therapy and self-

help groups offer support, but there is similar healing power in the passing of time, the support of friends, and the act of giving support and help to others (Baddeley & Singer, 2009; Brown et al., 2008; Neimeyer & Currier, 2009). Grieving spouses who talk often with others or receive grief counseling adjust about as well as those who grieve more privately (Bonanno, 2004; Stroebe et al., 2005).

“Consider, friend, as you pass by, as you are now, so once was I. As I am now, you too shall be. Prepare, therefore, to follow me.”

Scottish tombstone epitaph

Facing death with dignity and openness helps people complete the life cycle with a sense of life’s meaningfulness and unity—

Question

HiFHeBJlY0ZqmXQPKDgWGBO5ql/PvTwbTBZLVgyXvw7C6dZ55gF+KArq3rbXWN7Qev2NLV7hahyJr9ODp+LSgqcQR73tVbO8XS3nbvmFZIA9ivsZdz1SeY516MUdTQj47K+KEQmM3SWutRfSCtiMemosCrR3bKnN7srLXcMIlBj1hA31WzMum8L2DpMtF/5PQVbAsqCTOsiNmQp6g1a05vFtK/afnxaFWRnxZ190Qd6A5kleZmXkosujBUsy9QkZPO6+tDQZJMyDcoo6C+BMkVGj9yF05suIpDaleKteHOmzRkLXC5uM4iP9E66kZLQY226