7.2 Operant Conditioning

7-

It’s one thing to classically condition a dog to salivate at the sound of a tone, or a child to fear moving cars. To teach an elephant to walk on its hind legs or a child to say please, we turn to operant conditioning.

Classical conditioning and operant conditioning are both forms of associative learning, yet their differences are straightforward:

- Classical conditioning forms associations between stimuli (a CS and the US it signals). It also involves respondent behavior—actions that are automatic responses to a stimulus (such as salivating in response to meat powder and later in response to a tone).

- In operant conditioning, organisms associate their own actions with consequences. Actions followed by reinforcers increase; those followed by punishments often decrease. Behavior that operates on the environment to produce rewarding or punishing stimuli is called operant behavior.

operant conditioning a type of learning in which behavior is strengthened if followed by a reinforcer or diminished if followed by a punisher.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- With ______________ conditioning, we learn associations between events we do not control. With ______________ conditioning, we learn associations between our behavior and resulting events.

classical; operant

Skinner’s Experiments

law of effect Thorndike’s principle that behaviors followed by favorable consequences become more likely, and that behaviors followed by unfavorable consequences become less likely.

7-

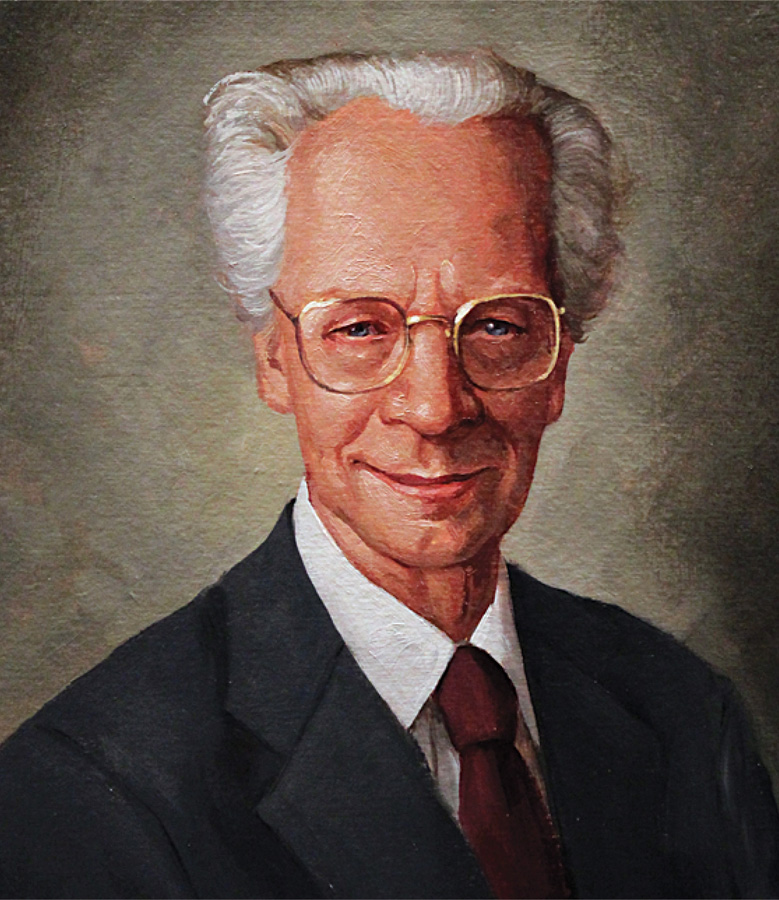

B. F. Skinner (1904–

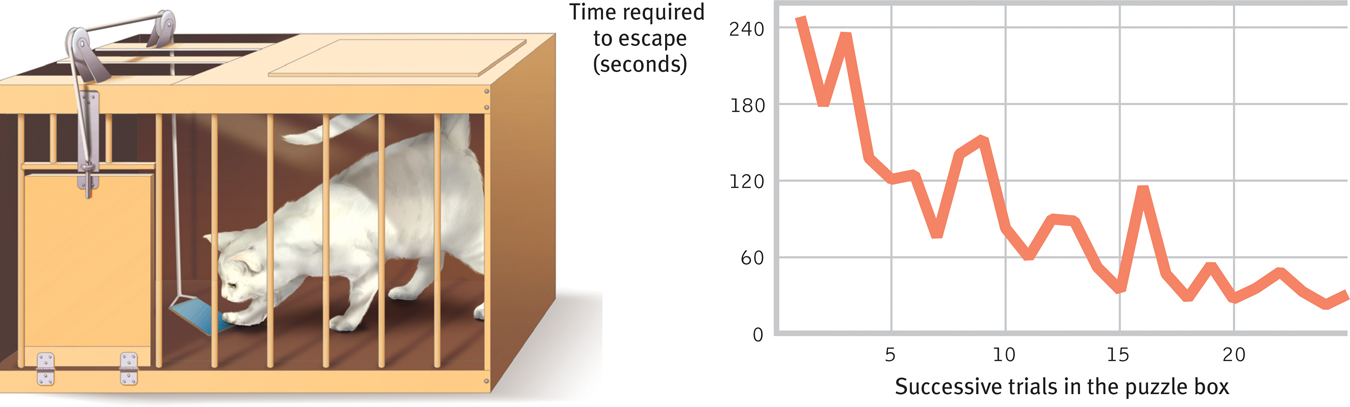

Figure 7.9

Figure 7.9Cat in a puzzle box Thorndike used a fish reward to entice cats to find their way out of a puzzle box (left) through a series of maneuvers. The cats’ performance tended to improve with successive trials (right), illustrating Thorndike’s law of effect. (Adapted from Thorndike, 1898.)

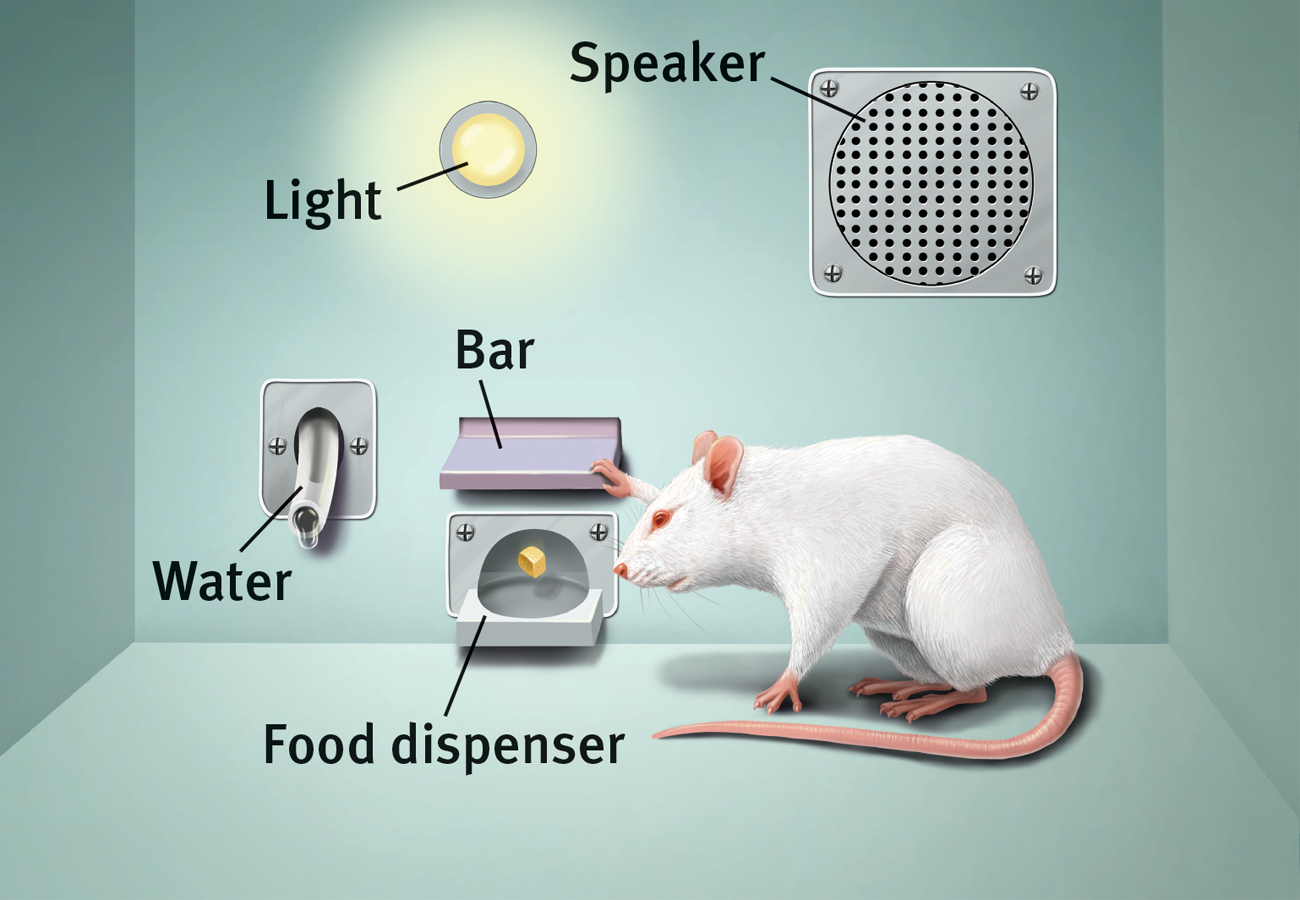

operant chamber in operant conditioning research, a chamber (also known as a Skinner box) containing a bar or key that an animal can manipulate to obtain a food or water reinforcer; attached devices record the animal’s rate of bar pressing or key pecking.

For his pioneering studies, Skinner designed an operant chamber, popularly known as a Skinner box (FIGURE 7.10). The box has a bar (a lever) that an animal presses—

Figure 7.10

Figure 7.10A Skinner box Inside the box, the rat presses a bar for a food reward. Outside, a measuring device (not shown here) records the animal’s accumulated responses.

reinforcement in operant conditioning, any event that strengthens the behavior it follows.

291

shaping an operant conditioning procedure in which reinforcers guide behavior toward closer and closer approximations of the desired behavior.

Shaping Behavior

Imagine that you wanted to condition a hungry rat to press a bar. Like Skinner, you could tease out this action with shaping, gradually guiding the rat’s actions toward the desired behavior. First, you would watch how the animal naturally behaves, so that you could build on its existing behaviors. You might give the rat a bit of food each time it approaches the bar. Once the rat is approaching regularly, you would give the food only when it moves close to the bar, then closer still. Finally, you would require it to touch the bar to get food. With this method of successive approximations, you reward responses that are ever closer to the final desired behavior, and you ignore all other responses. By making rewards contingent on desired behaviors, researchers and animal trainers gradually shape complex behaviors.

Shaping can also help us understand what nonverbal organisms perceive. Can a dog distinguish red and green? Can a baby hear the difference between lower-

Skinner noted that we continually reinforce and shape others’ everyday behaviors, though we may not mean to do so. Billy’s whining annoys his parents, for example, but consider how they typically respond:

| Billy: | Could you tie my shoes? |

| Father: | (Continues reading paper.) |

| Billy: | Dad, I need my shoes tied. |

| Father: | Uh, yeah, just a minute. |

| Billy: | DAAAAD! TIE MY SHOES! |

| Father: | How many times have I told you not to whine? Now, which shoe do we do first? |

Billy’s whining is reinforced, because he gets something desirable—

292

Or consider a teacher who pastes gold stars on a wall chart beside the names of children scoring 100 percent on spelling tests. As everyone can then see, some children consistently do perfect work. The others, who may have worked harder than the academic all-

Types of Reinforcers

7-

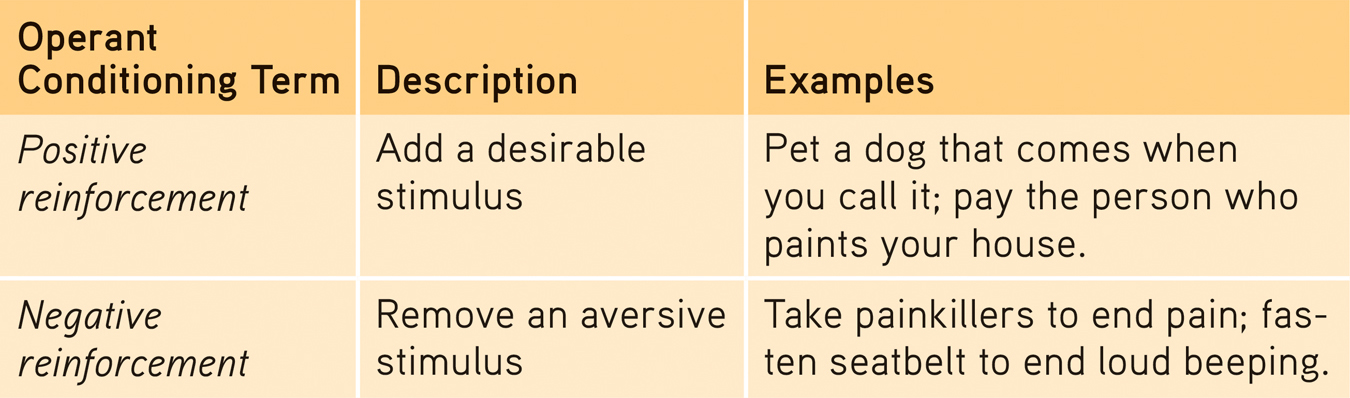

Until now, we’ve mainly been discussing positive reinforcement, which strengthens responding by presenting a typically pleasurable stimulus after a response. But, as we saw in the whining Billy story, there are two basic kinds of reinforcement (TABLE 7.1). Negative reinforcement strengthens a response by reducing or removing something negative. Billy’s whining was positively reinforced, because Billy got something desirable—

TABLE 7.1

TABLE 7.1Ways to Increase Behavior

positive reinforcement increasing behaviors by presenting positive reinforcers. A positive reinforcer is any stimulus that, when presented after a response, strengthens the response.

negative reinforcement increasing behaviors by stopping or reducing negative stimuli. A negative reinforcer is any stimulus that, when removed after a response, strengthens the response. (Note: Negative reinforcement is not punishment.)

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

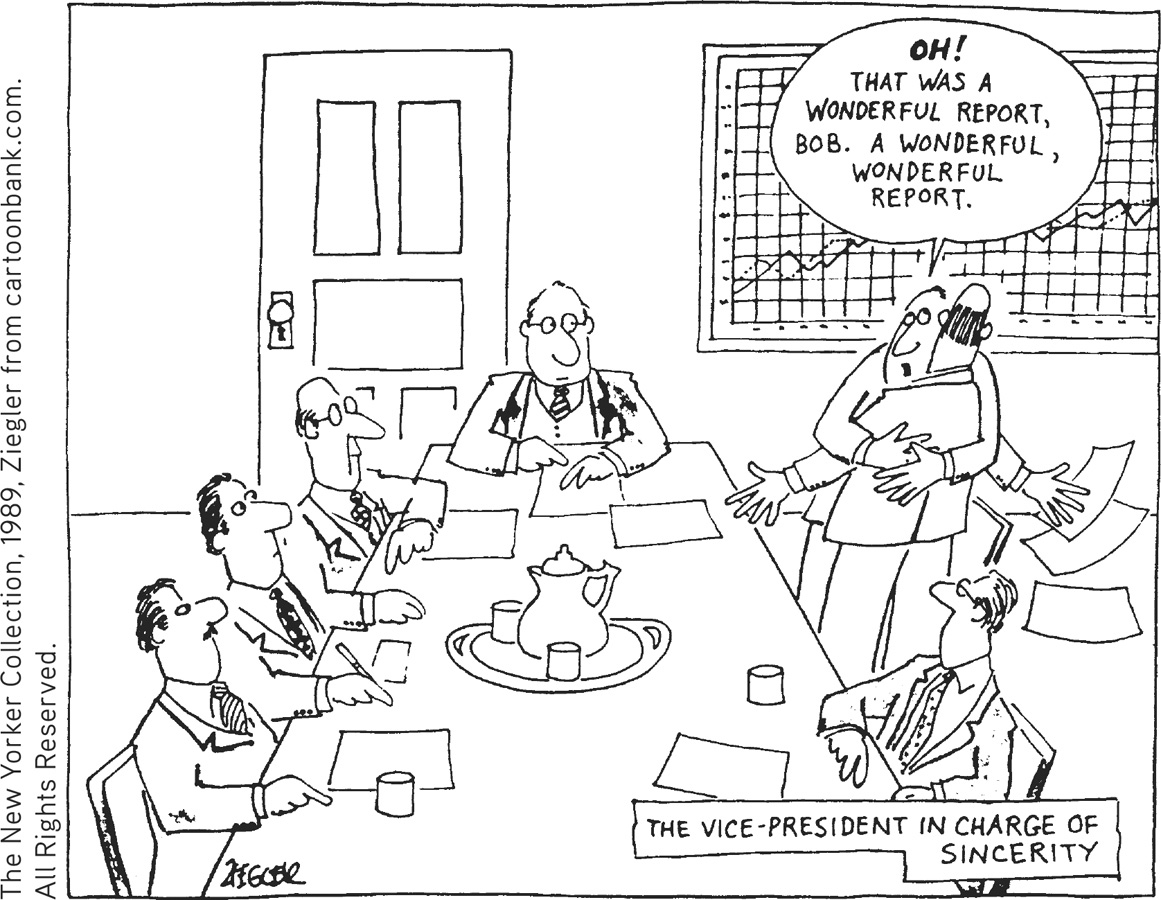

- How is operant conditioning at work in this cartoon?

The baby negatively reinforces her parents when she stops crying once they grant her wish. Her parents positively reinforce her cries by letting her sleep with them.

primary reinforcer an innately reinforcing stimulus, such as one that satisfies a biological need.

Sometimes negative and positive reinforcement coincide. Imagine a worried student who, after goofing off and getting a bad exam grade, studies harder for the next exam. This increased effort may be negatively reinforced by reduced anxiety, and positively reinforced by a better grade. We reap the rewards of escaping the aversive stimulus, which increases the chances that we will repeat our behavior. The point to remember: Whether it works by reducing something aversive, or by providing something desirable, reinforcement is any consequence that strengthens behavior.

conditioned reinforcer a stimulus that gains its reinforcing power through its association with a primary reinforcer; also known as a secondary reinforcer.

Primary and Conditioned Reinforcers Getting food when hungry or having a painful headache go away is innately satisfying. These primary reinforcers are unlearned. Conditioned reinforcers, also called secondary reinforcers, get their power through learned association with primary reinforcers. If a rat in a Skinner box learns that a light reliably signals a food delivery, the rat will work to turn on the light (see Figure 7.10). The light has become a conditioned reinforcer. Our lives are filled with conditioned reinforcers—

293

Immediate and Delayed Reinforcers Let’s return to the imaginary shaping experiment in which you were conditioning a rat to press a bar. Before performing this “wanted” behavior, the hungry rat will engage in a sequence of “unwanted” behaviors—

Unlike rats, humans do respond to delayed reinforcers: the paycheck at the end of the week, the good grade at the end of the semester, the trophy at the end of the season. Indeed, to function effectively we must learn to delay gratification. In laboratory testing, some 4-

To our detriment, small but immediate consequences (the enjoyment of watching late-

Question

uFLvMSU3/2fTY3ybz8JS3viJlZZt+/374OETHjAJhCqvxAt91zYD0IpuQyxbMlAw6tK+PA1zUkuOFFkGmUuLnggqSzPY4c+UJ+jmNvduRFC04p9hAZgOCN4wA+5/PXG6ZIHBtVt+/bB5wWHlQPHMmvMuMydLIRFvxOVs3CdqZ8LdRM8VDgv6qJMiDy01/n3tPiPyLqe/uKRcxyXiY833BuYf7GJR2yjMfUX5Q2BdExdsEY0XTlscnuwWOWMBuguhVgn6ahJyeAk6Sy/v+cmP1/NPk8Sin/pRu8gF5gG5/ZKlO3de3kiydk/YkYp9w/h2FLWROyKoV4sX/A79fpdEDKBwxiBgM0OJnd1TqdkQkEs5ozspStgVZAIEn4UsVO0bkPL76uwXq78=Reinforcement Schedules

reinforcement schedule a pattern that defines how often a desired response will be reinforced.

7-

continuous reinforcement schedule reinforcing the desired response every time it occurs.

In most of our examples, the desired response has been reinforced every time it occurs. But reinforcement schedules vary. With continuous reinforcement, learning occurs rapidly, which makes this the best choice for mastering a behavior. But extinction also occurs rapidly. When reinforcement stops—

partial (intermittent) reinforcement schedule reinforcing a response only part of the time; results in slower acquisition of a response but much greater resistance to extinction than does continuous reinforcement.

Real life rarely provides continuous reinforcement. Salespeople do not make a sale with every pitch. But they persist because their efforts are occasionally rewarded. This persistence is typical with partial (intermittent) reinforcement schedules, in which responses are sometimes reinforced, sometimes not. Learning is slower to appear, but resistance to extinction is greater than with continuous reinforcement. Imagine a pigeon that has learned to peck a key to obtain food. If you gradually phase out the food delivery until it occurs only rarely, in no predictable pattern, the pigeon may peck 150,000 times without a reward (Skinner, 1953). Slot machines reward gamblers in much the same way—

294

Lesson for parents: Partial reinforcement also works with children. Occasionally giving in to children’s tantrums for the sake of peace and quiet intermittently reinforces the tantrums. This is the very best procedure for making a behavior persist.

fixed-

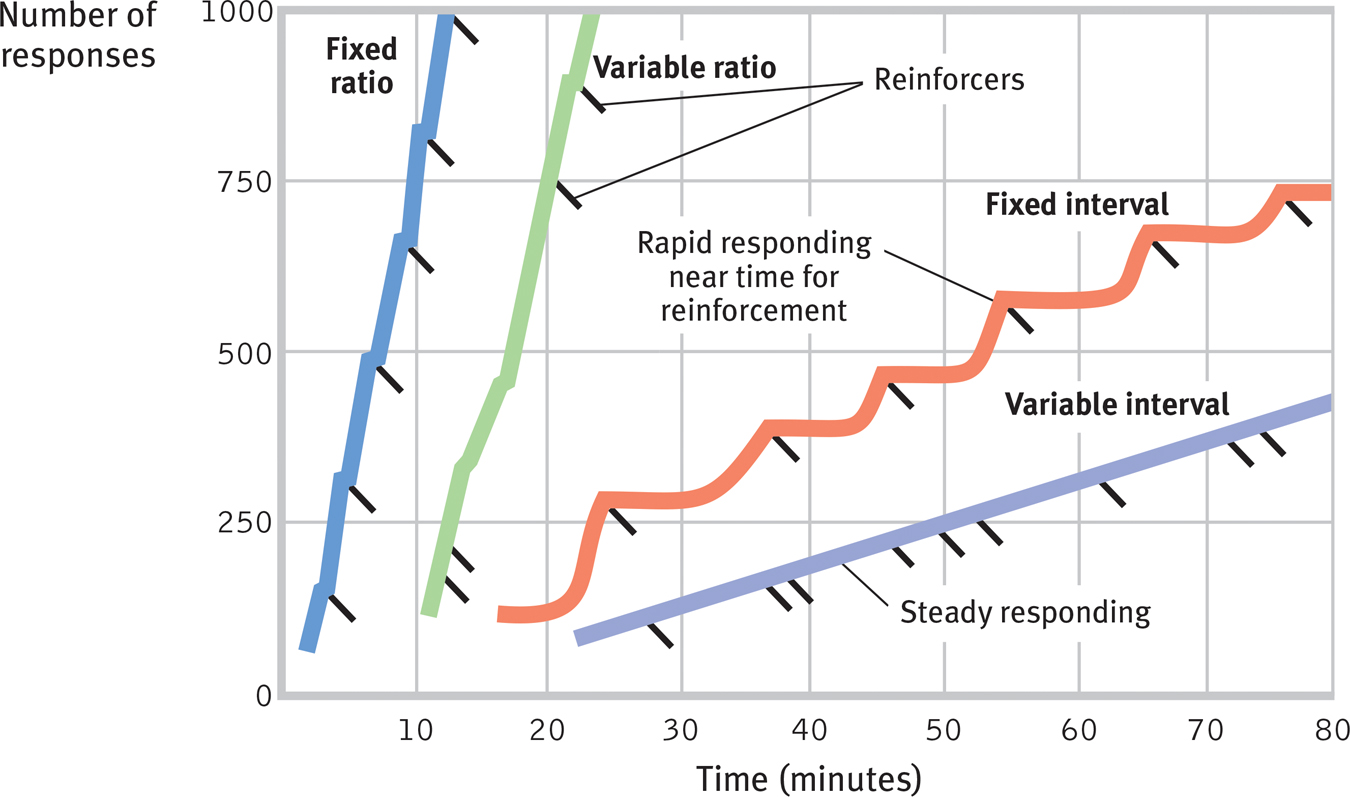

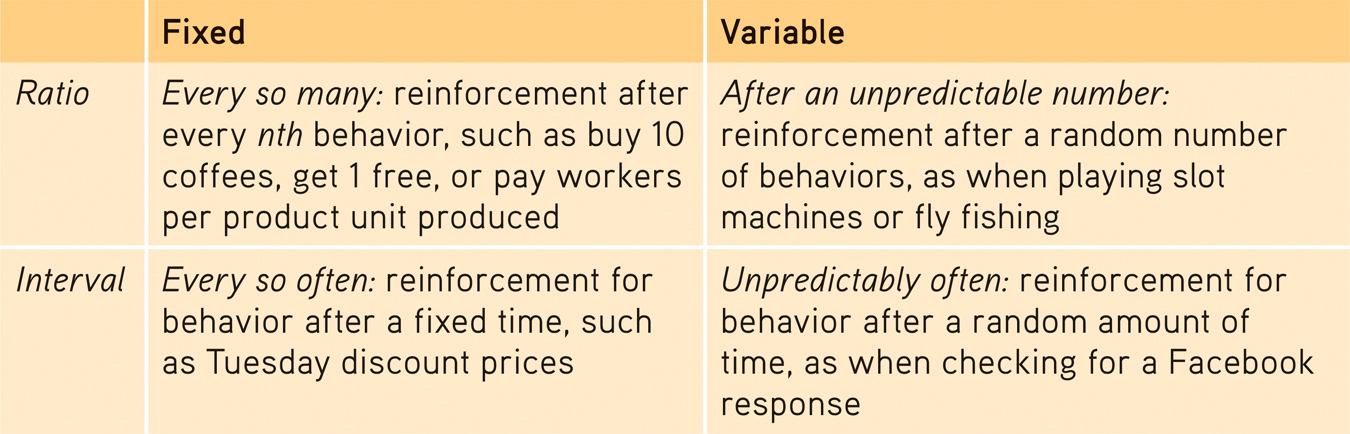

Skinner (1961) and his collaborators compared four schedules of partial reinforcement. Some are rigidly fixed, some unpredictably variable.

Fixed-ratio schedules reinforce behavior after a set number of responses. Coffee shops may reward us with a free drink after every 10 purchased. Once conditioned, rats may be reinforced on a fixed ratio of, say, one food pellet for every 30 responses. Once conditioned, animals will pause only briefly after a reinforcer before returning to a high rate of responding (FIGURE 7.11).

Figure 7.11

Figure 7.11Intermittent reinforcement schedules Skinner’s (1961) laboratory pigeons produced these response patterns to each of four reinforcement schedules. (Reinforcers are indicated by diagonal marks.) For people, as for pigeons, reinforcement linked to number of responses (a ratio schedule) produces a higher response rate than reinforcement linked to amount of time elapsed (an interval schedule). But the predictability of the reward also matters. An unpredictable (variable) schedule produces more consistent responding than does a predictable (fixed) schedule.

“The charm of fishing is that it is the pursuit of what is elusive but attainable, a perpetual series of occasions for hope.”

Scottish author John Buchan (1875–

variable-

fixed-

Variable-ratio schedules provide reinforcers after a seemingly unpredictable number of responses. This unpredictable reinforcement is what slot-

Fixed-interval schedules reinforce the first response after a fixed time period. Animals on this type of schedule tend to respond more frequently as the anticipated time for reward draws near. People check more frequently for the mail as the delivery time approaches. A hungry child jiggles the Jell-

Variable-interval schedules reinforce the first response after varying time intervals. Like the longed-

TABLE 7.2

TABLE 7.2Schedules of Reinforcement

variable-

In general, response rates are higher when reinforcement is linked to the number of responses (a ratio schedule) rather than to time (an interval schedule). But responding is more consistent when reinforcement is unpredictable (a variable schedule) than when it is predictable (a fixed schedule). Animal behaviors differ, yet Skinner (1956) contended that the reinforcement principles of operant conditioning are universal. It matters little, he said, what response, what reinforcer, or what species you use. The effect of a given reinforcement schedule is pretty much the same: “Pigeon, rat, monkey, which is which? It doesn’t matter…. Behavior shows astonishingly similar properties.”

295

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Telemarketers are reinforced by which schedule? People checking the oven to see if the cookies are done are on which schedule? Airline frequent-

flyer programs that offer a free flight after every 25,000 miles of travel are using which reinforcement schedule?

Telemarketers are reinforced on a variable-

Punishment

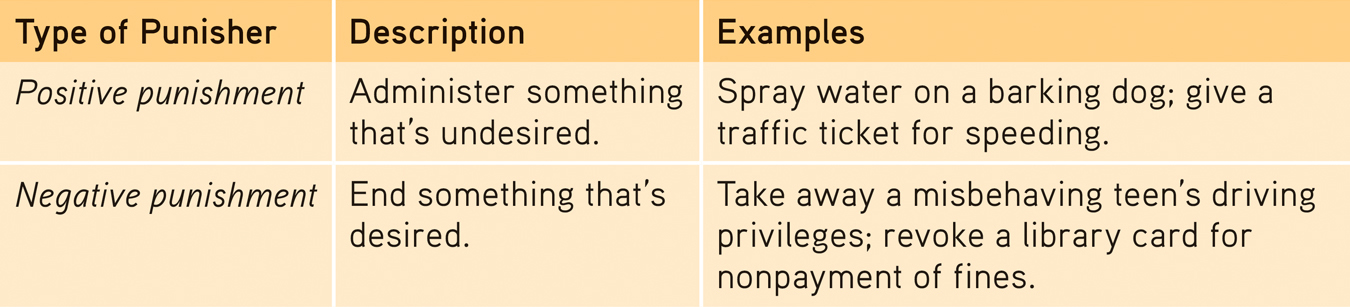

7-

Reinforcement increases a behavior; punishment does the opposite. A punisher is any consequence that decreases the frequency of a preceding behavior (TABLE 7.3). Swift and sure punishers can powerfully restrain unwanted behavior. The rat that is shocked after touching a forbidden object and the child who is burned by touching a hot stove will learn not to repeat those behaviors. A dog that has learned to come running at the sound of an electric can opener will stop coming if its owner runs the machine to attract the dog and then banish it to the basement. Children’s compliance often increases after a reprimand and a “time out” punishment (Owen et al., 2012).

TABLE 7.3

TABLE 7.3Ways to Decrease Behavior

punishment an event that tends to decrease the behavior that it follows.

Criminal behavior, much of it impulsive, is also influenced more by swift and sure punishers than by the threat of severe sentences (Darley & Alter, 2012). Thus, when Arizona introduced an exceptionally harsh sentence for first-

296

How should we interpret the punishment studies in relation to parenting practices? Many psychologists and supporters of nonviolent parenting note four major drawbacks of physical punishment (Gershoff, 2002; Marshall, 2002).

- Punished behavior is suppressed, not forgotten. This temporary state may (negatively) reinforce parents’ punishing behavior. The child swears, the parent swats, the parent hears no more swearing and feels the punishment successfully stopped the behavior. No wonder spanking is a hit with so many U.S. parents of 3-

and 4- year- olds— more than 9 in 10 of whom acknowledged spanking their children (Kazdin & Benjet, 2003). - Punishment teaches discrimination among situations. In operant conditioning, discrimination occurs when an organism learns that certain responses, but not others, will be reinforced. Did the punishment effectively end the child’s swearing? Or did the child simply learn that while it’s not okay to swear around the house, it’s okay to swear elsewhere?

- Punishment can teach fear. In operant conditioning, generalization occurs when an organism’s response to similar stimuli is also reinforced. A punished child may associate fear not only with the undesirable behavior but also with the person who delivered the punishment or where it occurred. Thus, children may learn to fear a punishing teacher and try to avoid school, or may become more anxious (Gershoff et al., 2010). For such reasons, most European countries and most U.S. states now ban hitting children in schools and child-

care institutions (stophitting.com). Thirty- three countries, including those in Scandinavia, further outlaw hitting by parents, providing children the same legal protection given to spouses. - Physical punishment may increase aggression by modeling aggression as a way to cope with problems. Studies find that spanked children are at increased risk for aggression (MacKenzie et al., 2013). We know, for example, that many aggressive delinquents and abusive parents come from abusive families (Straus & Gelles, 1980; Straus et al., 1997).

Some researchers note a problem. Well, yes, they say, physically punished children may be more aggressive, for the same reason that people who have undergone psychotherapy are more likely to suffer depression—

If one adjusts for preexisting antisocial behavior, then an occasional single swat or two to misbehaving 2-

- The swat is used only as a backup when milder disciplinary tactics, such as a time-

out (removing children from reinforcing surroundings) fail. - The swat is combined with a generous dose of reasoning and reinforcing.

Other researchers remain unconvinced. After controlling for prior misbehavior, they report that more frequent spankings of young children predict future aggressiveness (Grogan-

Parents of delinquent youths are often unaware of how to achieve desirable behaviors without screaming, hitting, or threatening their children with punishment (Patterson et al., 1982). Training programs can help transform dire threats (“You clean up your room this minute or no dinner!”) into positive incentives (“You’re welcome at the dinner table after you get your room cleaned up”). Stop and think about it. Aren’t many threats of punishment just as forceful, and perhaps more effective, when rephrased positively? Thus, “If you don’t get your homework done, there’ll be no car” would better be phrased as….

297

In classrooms, too, teachers can give feedback on papers by saying, “No, but try this…” and “Yes, that’s it!” Such responses reduce unwanted behavior while reinforcing more desirable alternatives. Remember: Punishment tells you what not to do; reinforcement tells you what to do. Thus, punishment trains a particular sort of morality—

What punishment often teaches, said Skinner, is how to avoid it. Most psychologists now favor an emphasis on reinforcement: Notice people doing something right and affirm them for it.

Question

q433URgt7JO9/cDAUBtllpQoUbbZJJ+hCSGKbK/AWRweZWSueb1G5pM2OSAeu2xPYjK4Zsb0w49e8eXn0Z810kIDWkLU59Xlnv97fX/fHRlhfRxRKnStnSSRolCLuObQnFB+d+u1RokV7+foG/J1e5rOGfdTxsPjj9LsNmuoRhrl8tMeHVxa8ugFL1K2FDwsjWPRuBVXzFEcOUMb0Q0SNUwwuaLsp01Ij+sBoL2aOSeOaSYGwWrZCykhjFkG2Vquq1OZaqgWSi8yWHH1uiRwnglfh9GSGDPt4xFenQW28eQEa0SRqbdwKBfaDG95P3UzPi1IVWMHrjA=RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

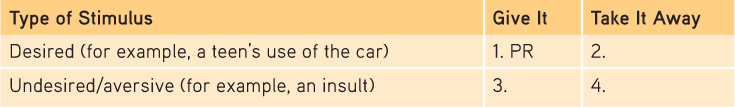

- Fill in the three blanks below with one of the following terms: positive reinforcement (PR), negative reinforcement (NR), positive punishment (PP), and negative punishment (NP). We have provided the first answer (PR) for you.

1. PR (positive reinforcement); 2. NP (negative punishment); 3. PP (positive punishment); 4. NR (negative reinforcement)

Skinner’s Legacy

7-

B. F. Skinner stirred a hornet’s nest with his outspoken beliefs. He repeatedly insisted that external influences, not internal thoughts and feelings, shape behavior. And he urged people to use operant principles to influence others’ behavior at school, work, and home. Knowing that behavior is shaped by its results, he argued that we should use rewards to evoke more desirable behavior.

Skinner’s critics objected, saying that he dehumanized people by neglecting their personal freedom and by seeking to control their actions. Skinner’s reply: External consequences already haphazardly control people’s behavior. Why not administer those consequences toward human betterment? Wouldn’t reinforcers be more humane than the punishments used in homes, schools, and prisons? And if it is humbling to think that our history has shaped us, doesn’t this very idea also give us hope that we can shape our future? In such ways, and through his ideas for positively reinforcing character strengths, Skinner actually anticipated some of today’s positive psychology (Adams, 2012).

To review and experience simulations of operant conditioning, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Operant Conditioning and also Shaping.

To review and experience simulations of operant conditioning, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Operant Conditioning and also Shaping.

Applications of Operant Conditioning

In later chapters, we will see how psychologists apply operant conditioning principles to help people moderate high blood pressure or gain social skills. Reinforcement technologies are also at work in schools, sports, workplaces, and homes, and these principles can support our self-

At School A generation ago, Skinner envisioned a day when teaching machines and textbooks would shape learning in small steps, immediately reinforcing correct responses. He believed such machines and texts would revolutionize education and free teachers to focus on each student’s special needs.

298

Stand in Skinner’s shoes for a moment and imagine two math teachers, each with a class of students ranging from whiz kids to slow learners. Teacher A gives the whole class the same lesson, knowing that some kids will breeze through the math concepts, while others will be frustrated and fail. Teacher B, faced with a similar class, paces the material according to each student’s rate of learning and provides prompt feedback, with positive reinforcement, to both the slow and the fast learners. Thinking as Skinner did, how might you achieve the individualized instruction of Teacher B?

Computers were Skinner’s final hope. “Good instruction demands two things,” he said. “Students must be told immediately whether what they do is right or wrong and, when right, they must be directed to the step to be taken next.” Thus, the computer could be Teacher B—

In Sports The key to shaping behavior in athletic performance, as elsewhere, is first reinforcing small successes and then gradually increasing the challenge. Golf students can learn putting by starting with very short putts, and then, as they build mastery, stepping back farther and farther. Novice batters can begin with half swings at an oversized ball pitched from 10 feet away, giving them the immediate pleasure of smacking the ball. As the hitters’ confidence builds with their success and they achieve mastery at each level, the pitcher gradually moves back—

At Work Knowing that reinforcers influence productivity, many organizations have invited employees to share the risks and rewards of company ownership. Others focus on reinforcing a job well done. Rewards are most likely to increase productivity if the desired performance has been well defined and is achievable. The message for managers? Reward specific, achievable behaviors, not vaguely defined “merit.”

Operant conditioning also reminds us that reinforcement should be immediate. IBM legend Thomas Watson understood this. When he observed an achievement, he wrote the employee a check on the spot (Peters & Waterman, 1982). But rewards need not be material, or lavish. An effective manager may simply walk the floor and sincerely affirm people for good work, or write notes of appreciation for a completed project. As Skinner said, “How much richer would the whole world be if the reinforcers in daily life were more effectively contingent on productive work?”

At Home As we have seen, parents can learn from operant conditioning practices. Parent-

To disrupt this cycle, parents should remember that basic rule of shaping: Notice people doing something right and affirm them for it. Give children attention and other reinforcers when they are behaving well. Target a specific behavior, reward it, and watch it increase. When children misbehave or are defiant, don’t yell at them or hit them. Simply explain the misbehavior and give them a time-

299

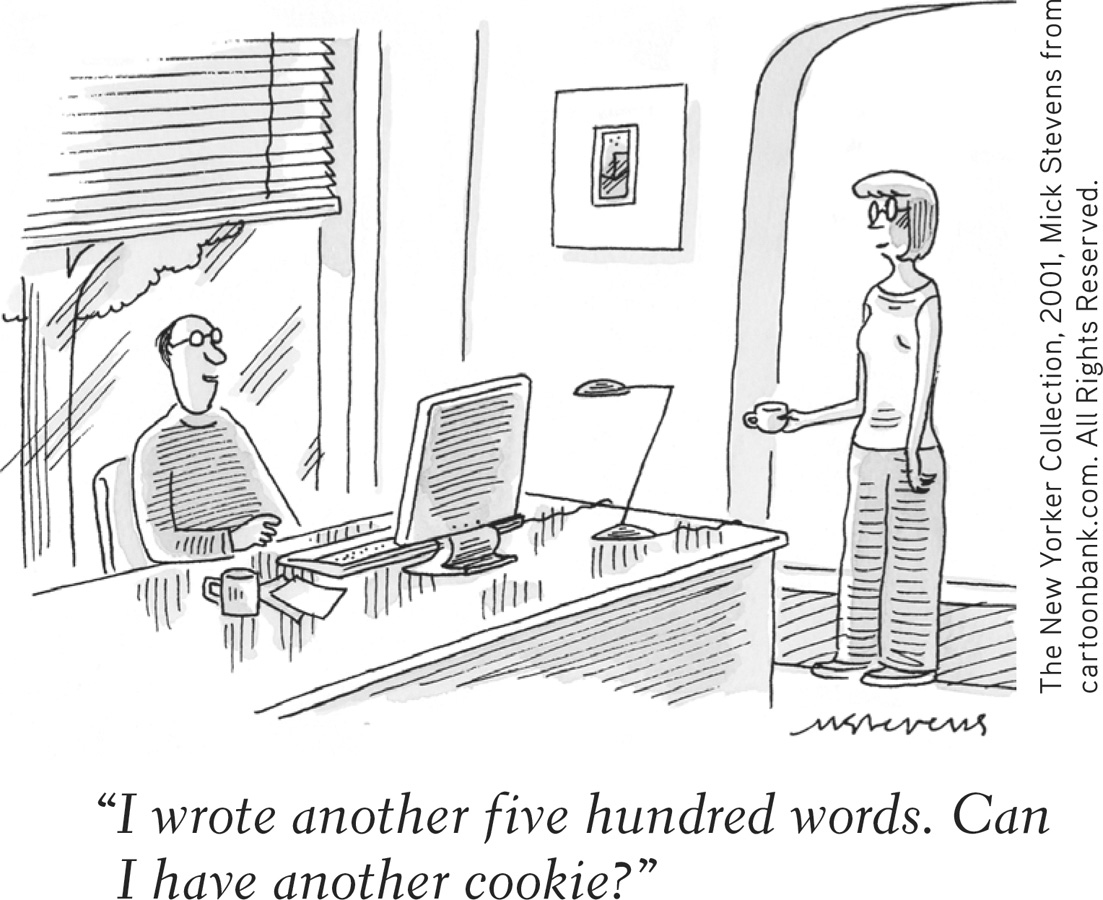

Finally, we can use operant conditioning in our own lives. To reinforce your own desired behaviors (perhaps to improve your study habits) and extinguish the undesired ones (to stop smoking, for example), psychologists suggest taking these steps:

Conditioning principles may also be applied in clinical settings. Explore some of these applications in LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If People Can Learn to Reduce Anxiety?

- State a realistic goal in measurable terms. You might, for example, aim to boost your study time by an hour a day.

- Decide how, when, and where you will work toward your goal. Take time to plan. Those who specify how they will implement goals more often fulfill them (Gollwitzer & Oettingen, 2012).

- Monitor how often you engage in your desired behavior. You might log your current study time, noting under what conditions you do and don’t study. (When I [DM] began writing textbooks, I logged how I spent my time each day and was amazed to discover how much time I was wasting. I [ND] experienced a similar rude awakening when I started tracking my daily writing hours.)

- Reinforce the desired behavior. To increase your study time, give yourself a reward (a snack or some activity you enjoy) only after you finish your extra hour of study. Agree with your friends that you will join them for weekend activities only if you have met your realistic weekly studying goal.

- Reduce the rewards gradually. As your new behaviors become more habitual, give yourself a mental pat on the back instead of a cookie.

Question

bXn0KO/Fi9uGnbxdYMmGe2E1ecSkZzdNqc8VyMoCvWMgrBhdEzvPixnrWPLIN1hmy+7n04JhU8RrIomnd/SI826PAymoQSK51MS/9nz3H5Id1uJUdmk5sTVzwnvCxJn/9aNnd4h1nUZ5D/PXwVAo6E9cc8rgdtVAZ5L3YoB8suTt+w3uzK+V9rPLxCmn/w9+yVOO+d0Ermp5bjpgl078haZfET8i58Ga2ZFEqXkyGN/2BZjHpkFHcCMouIrJeDwlxPYqFntiZllJ1l1zContrasting Classical and Operant Conditioning

7-

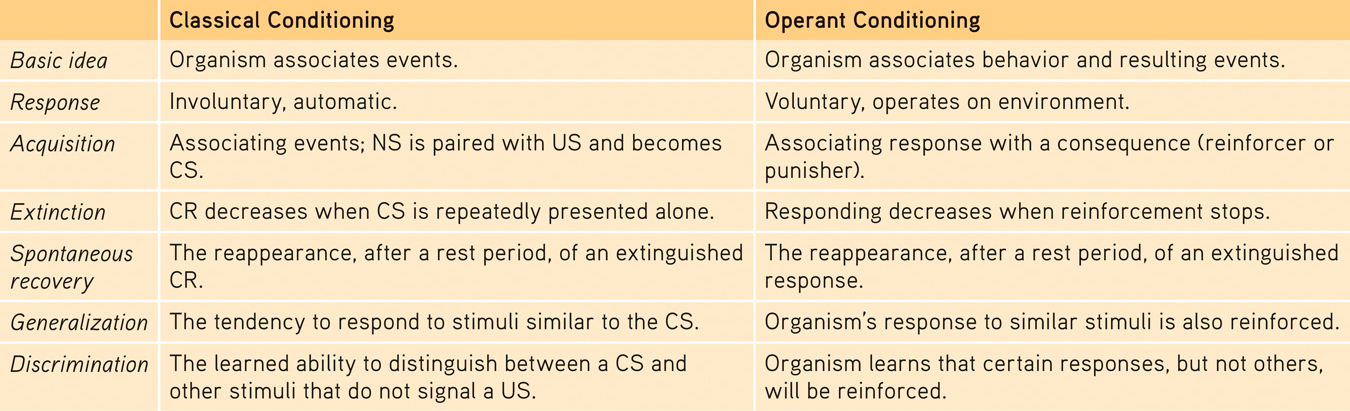

Both classical and operant conditioning are forms of associative learning. Both involve acquisition, extinction, spontaneous recovery, generalization, and discrimination. But these two forms of learning also differ. Through classical (Pavlovian) conditioning, we associate different stimuli we do not control, and we respond automatically (respondent behaviors) (TABLE 7.4). Through operant conditioning, we associate our own behaviors—

TABLE 7.4

TABLE 7.4Comparison of Classical and Operant Conditioning

“O! This learning, what a thing it is.”

William Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew, 1597

As we shall see next, our biology and cognitive processes influence both classical and operant conditioning.

300

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Salivating in response to a tone paired with food is a(n) ______________ behavior; pressing a bar to obtain food is a(n) ______________ behavior.

respondent; operant