8.3 Forgetting, Memory Construction, and Improving Memory

Please continue to the next section.

Forgetting

8-

Amid all the applause for memory—

“Amnesia seeps into the crevices of our brains, and amnesia heals.”

Joyce Carol Oates, “Words Fail, Memory Blurs, Life Wins,” 2001

A more recent case of a life overtaken by memory is “A. J.,” whose experience has been studied and verified by a University of California at Irvine research team, along with several dozen other “highly superior autobiographical memory” cases (McGaugh & LePort, 2014; Parker et al., 2006). A. J., who has identified herself as Jill Price, compares her memory to “a running movie that never stops. It’s like a split screen. I’ll be talking to someone and seeing something else…. Whenever I see a date flash on the television (or anywhere for that matter) I automatically go back to that day and remember where I was, what I was doing, what day it fell on, and on and on and on and on. It is nonstop, uncontrollable, and totally exhausting.” A good memory is helpful, but so is the ability to forget. If a memory-

More often, however, our unpredictable memory dismays and frustrates us. Memories are quirky. My [DM] own memory can easily call up such episodes as that wonderful first kiss with the woman I love, or trivial facts like the air mileage from London to Detroit. Then it abandons me when I discover I have failed to encode, store, or retrieve a student’s name or where I left my sunglasses.

anterograde amnesia an inability to form new memories.

Forgetting and the Two-

retrograde amnesia an inability to retrieve information from one’s past.

For some, memory loss is severe and permanent. Consider Henry Molaison (known as “H. M.,” 1926–

Molaison suffered from anterograde amnesia—he could recall his past, but he could not form new memories. (Those who cannot recall their past—

Neurologist Oliver Sacks (1985, pp. 26–

339

When Jimmie gave his age as 19, Sacks set a mirror before him: “Look in the mirror and tell me what you see. Is that a 19-

Jimmie turned ashen, gripped the chair, cursed, then became frantic: “What’s going on? What’s happened to me? Is this a nightmare? Am I crazy? Is this a joke?” When his attention was diverted to some children playing baseball, his panic ended, the dreadful mirror forgotten.

Sacks showed Jimmie a photo from National Geographic. “What is this?” he asked.

“It’s the Moon,” Jimmie replied.

“No, it’s not,” Sacks answered. “It’s a picture of the Earth taken from the Moon.”

“Doc, you’re kidding! Someone would’ve had to get a camera up there!”

“Naturally.”

“Hell! You’re joking—

For a 6-

For a 6-

Careful testing of these unique people reveals something even stranger: Although incapable of recalling new facts or anything they have done recently, Molaison, Jimmie, and others with similar conditions can learn nonverbal tasks. Shown hard-

Molaison and Jimmie lost their ability to form new explicit memories, but their automatic processing ability remained intact. Like Alzheimer’s patients, whose explicit memories for new people and events are lost, they could form new implicit memories (Lustig & Buckner, 2004). These patients can learn how to do something, but they will have no conscious recall of learning their new skill. Such sad cases confirm that we have two distinct memory systems, controlled by different parts of the brain.

For most of us, forgetting is a less drastic process. Let’s consider some of the reasons we forget.

Encoding Failure

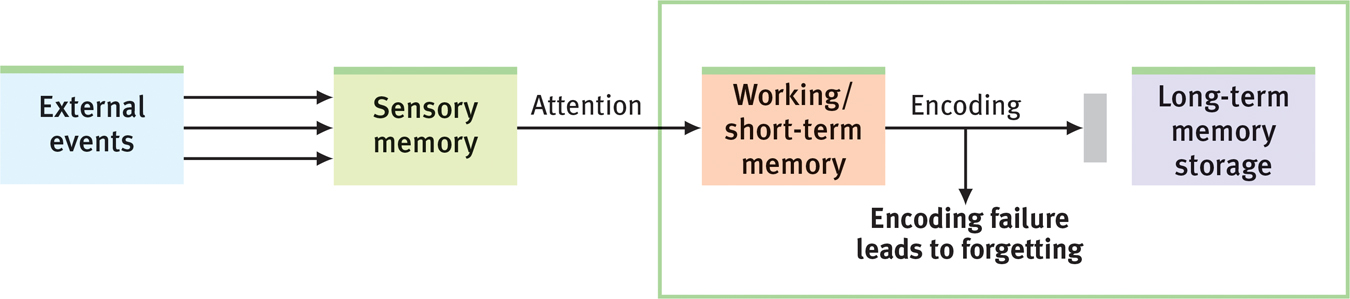

Much of what we sense we never notice, and what we fail to encode, we will never remember (FIGURE 8.16 below). The English novelist and critic C. S. Lewis (1967, p. 107) described the enormity of what we never encode:

Each of us finds that in [our] own life every moment of time is completely filled. [We are] bombarded every second by sensations, emotions, thoughts … nine-

Figure 8.16

Figure 8.16Forgetting as encoding failure We cannot remember what we have not encoded.

Age can affect encoding efficiency. The brain areas that jump into action when young adults encode new information are less responsive in older adults. This slower encoding helps explain age-

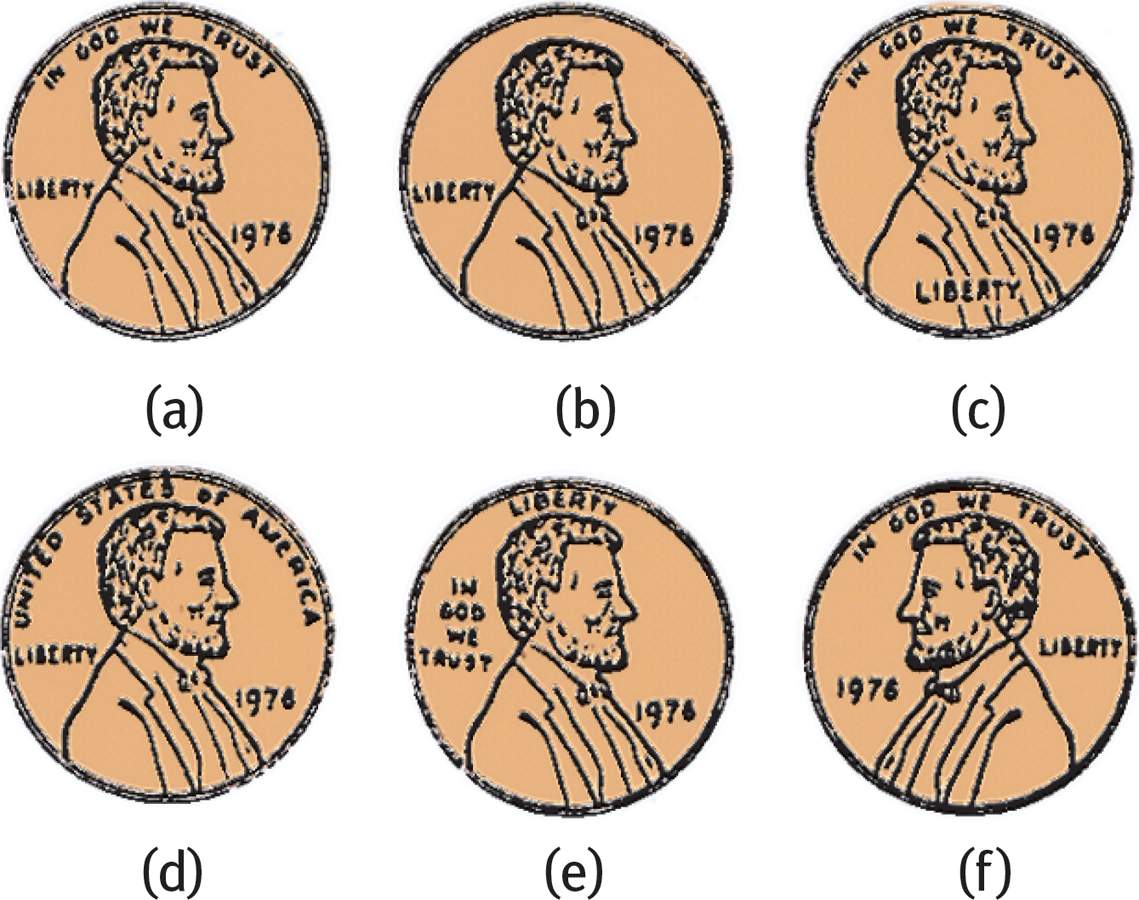

But no matter how young we are, we selectively attend to few of the myriad sights and sounds continually bombarding us. Consider this example: If you live in the United States, you have looked at thousands of pennies in your lifetime. You can surely recall their color and size, but can you recall what the side with the head looks like? If not, let’s make the memory test easier: If you are familiar with U.S. coins, can you, in FIGURE 8.17, just recognize the real thing? Most people cannot (Nickerson & Adams, 1979). Likewise, few British people can draw from memory the details of a one-

Figure 8.17

Figure 8.17Test your memory Which of these U.S. pennies is the real thing? (If you live outside the United States, try drawing one of your own country’s coins.) (From Nickerson & Adams, 1979.) See answer below.

The first penny (a) is the real penny.

340

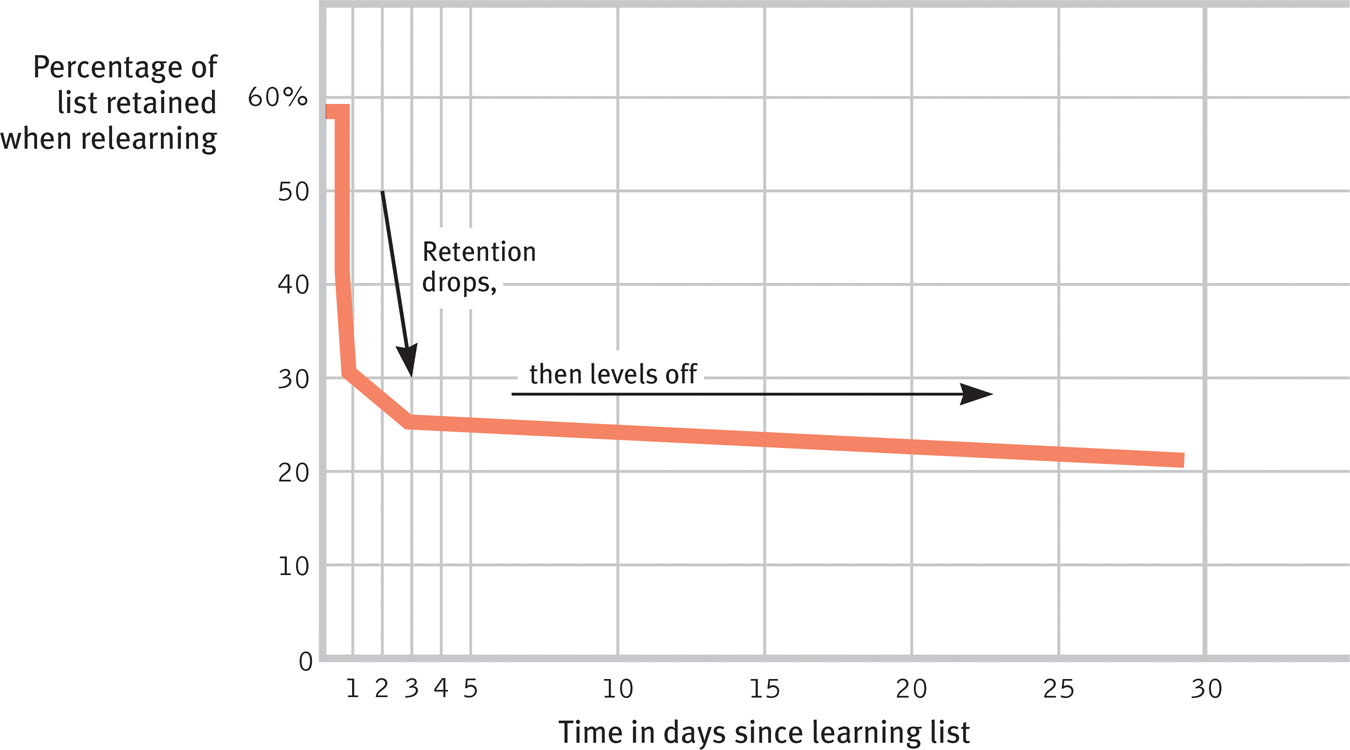

Storage Decay

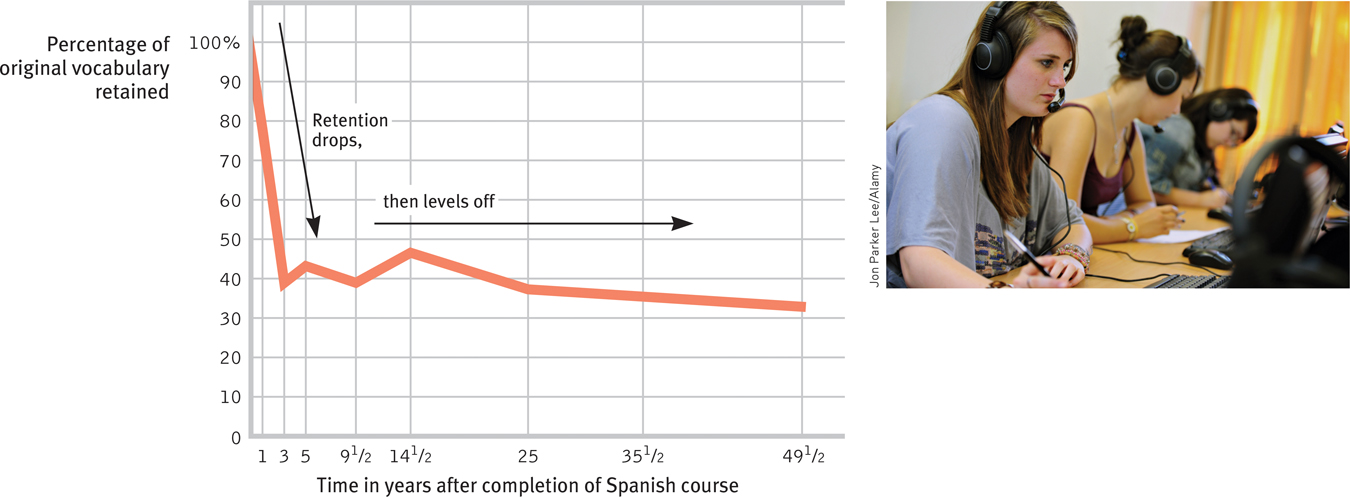

Even after encoding something well, we sometimes later forget it. To study the durability of stored memories, Ebbinghaus (1885) learned more lists of nonsense syllables and measured how much he retained when relearning each list, from 20 minutes to 30 days later. The result, confirmed by later experiments, was his famous forgetting curve: The course of forgetting is initially rapid, then levels off with time (FIGURE 8.18; Wixted & Ebbesen, 1991). Harry Bahrick (1984) found a similar forgetting curve for Spanish vocabulary learned in school. Compared with those just completing a high school or college Spanish course, people 3 years out of school had forgotten much of what they had learned (FIGURE 8.19). However, what people remembered then, they still remembered 25 and more years later. Their forgetting had leveled off.

Figure 8.18

Figure 8.18Ebbinghaus’ forgetting curve After learning lists of nonsense syllables, such as YOX and JIH, Ebbinghaus studied how much he retained up to 30 days later. He found that memory for novel information fades quickly, then levels out. (Data from Ebbinghaus, 1885.)

Figure 8.19

Figure 8.19The forgetting curve for Spanish learned in school Compared with people just completing a Spanish course, those 3 years out of the course remembered much less (on a vocabulary recognition test). Compared with the 3-

One explanation for these forgetting curves is a gradual fading of the physical memory trace. Cognitive neuroscientists are getting closer to solving the mystery of the physical storage of memory and are increasing our understanding of how memory storage could decay. Like books you can’t find in your campus library, memories may be inaccessible for many reasons. Some were never acquired (not encoded). Others were discarded (stored memories decay). And others are out of reach because we can’t retrieve them.

341

Retrieval Failure

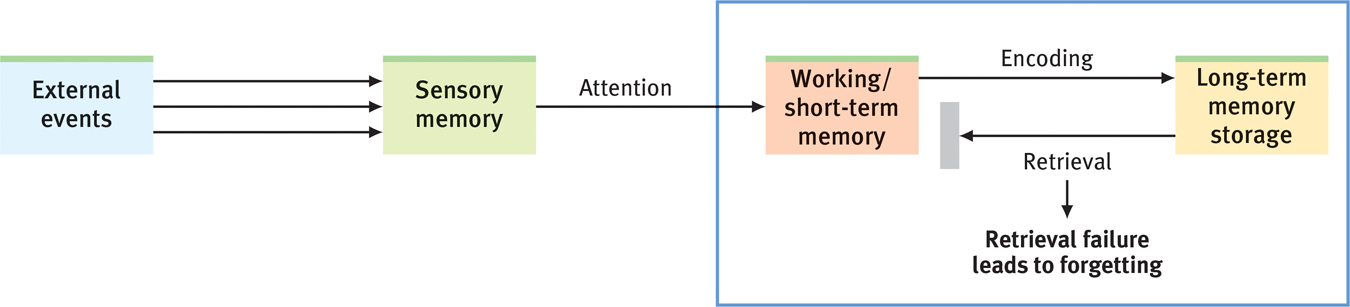

Often, forgetting is not memories faded but memories unretrieved. We store in long-

Figure 8.20

Figure 8.20Retrieval failure Sometimes even stored information cannot be accessed, which leads to forgetting.

Do you recall the gist of the second sentence we asked you to remember? If not, does the word shark serve as a retrieval cue? Experiments show that shark (likely what you visualized) more readily retrieves the image you stored than does the sentence’s actual word, fish (Anderson et al., 1976). (The sentence was “The fish attacked the swimmer.”)

But retrieval problems occasionally stem from interference and, perhaps, from motivated forgetting.

Deaf persons fluent in sign language experience a parallel “tip of the fingers” phenomenon (Thompson et al., 2005).

proactive interference the forward-

retroactive interference the backward-

Interference As you collect more and more information, your mental attic never fills, but it surely gets cluttered. An ability to tune out clutter helps people to focus, and focusing helps us recall information. Sometimes, however, clutter wins, and new learning and old collide. Proactive (forward-

Retroactive (backward-

342

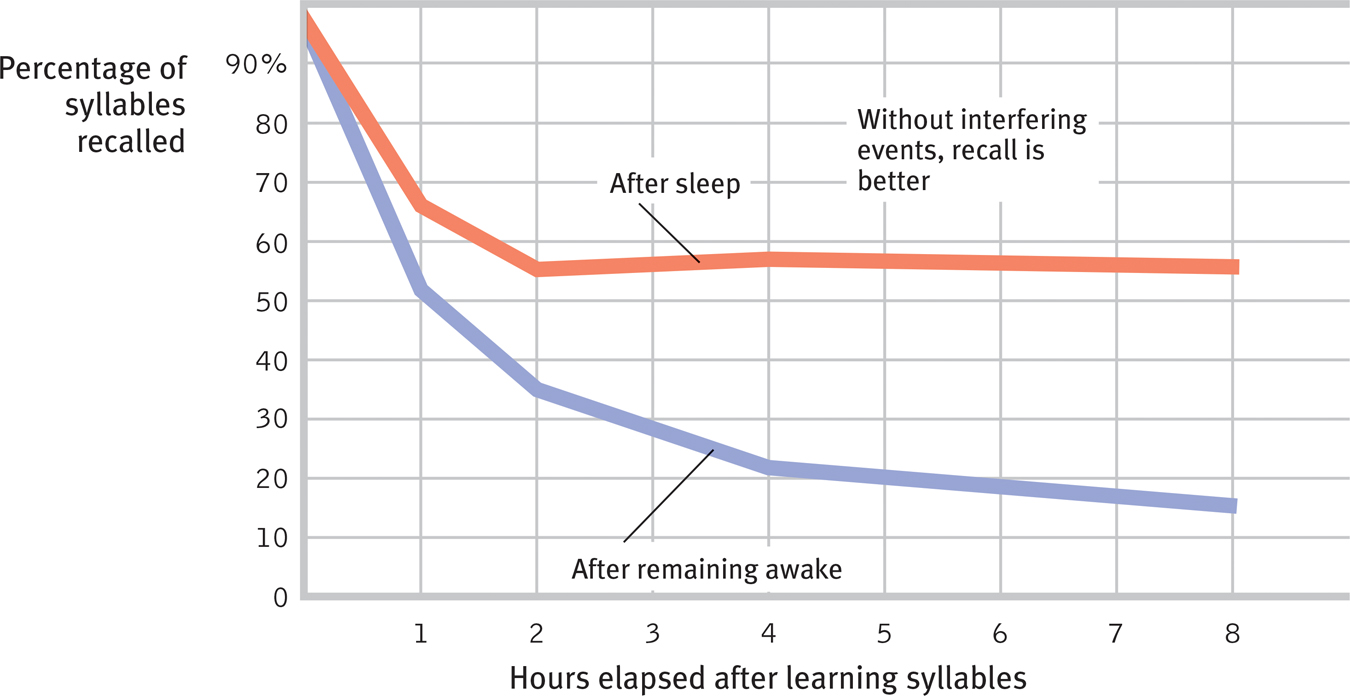

Information presented in the hour before sleep is protected from retroactive interference because the opportunity for interfering events is minimized (Diekelmann & Born, 2010; Nesca & Koulack, 1994). Researchers John Jenkins and Karl Dallenbach (1924) first discovered this in a now-

Figure 8.21

Figure 8.21Retroactive interference More forgetting occurred when a person stayed awake and experienced other new material. (Data from Jenkins & Dallenbach, 1924.)

The hour before sleep is a good time to commit information to memory (Scullin & McDaniel, 2010), though information presented in the seconds just before sleep is seldom remembered (Wyatt & Bootzin, 1994). If you’re considering learning while sleeping, forget it. We have little memory for information played aloud in the room during sleep, although the ears do register it (Wood et al., 1992).

Old and new learning do not always compete with each other, of course. Previously learned information (Latin) often facilitates our learning of new information (French). This phenomenon is called positive transfer.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of interference effects on memory, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Forgetting.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of interference effects on memory, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Forgetting.

Motivated Forgetting To remember our past is often to revise it. Years ago, the huge cookie jar in my [DM] kitchen was jammed with freshly baked chocolate chip cookies. Still more were cooling across racks on the counter. Twenty-

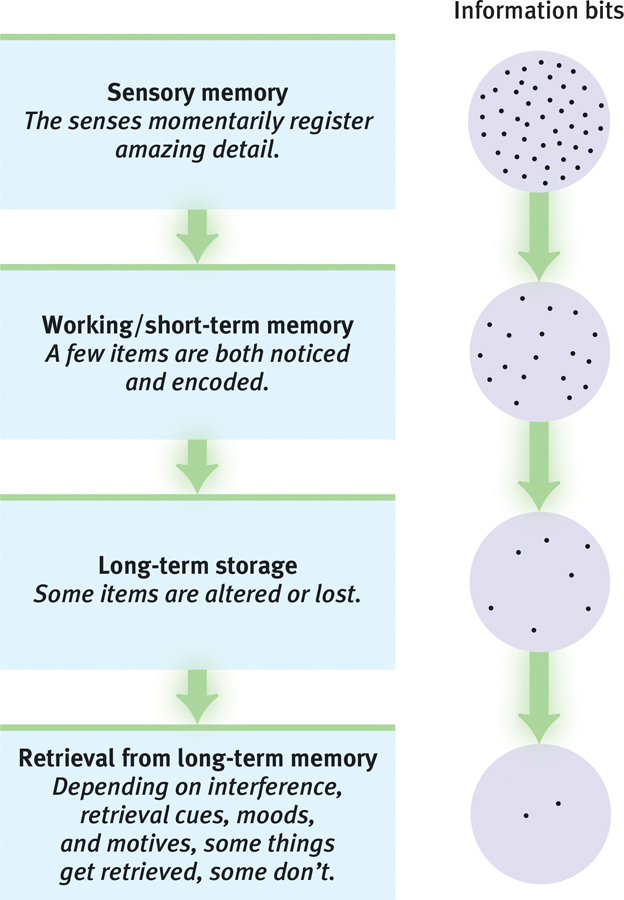

Why do our memories fail us? This happens in part because memory is an “unreliable, self-

FIGURE 8.22 reminds us that as we process information we filter, alter, or lose much of it. So why were my family and I so far off in our estimates of the cookies we had eaten? Was it an encoding problem? (Did we just not notice what we had eaten?) Was it a storage problem? (Might our memories of cookies, like Ebbinghaus’ memory of nonsense syllables, have melted away almost as fast as the cookies themselves?) Or was the information still intact but not retrievable because it would be embarrassing to remember?2

Figure 8.22

Figure 8.22When do we forget? Forgetting can occur at any memory stage. As we process information, we filter, alter, or lose much of it.

repression in psychoanalytic theory, the basic defense mechanism that banishes from consciousness anxiety-

343

Sigmund Freud might have argued that our memory systems self-

Question

t9DxCvagLCg4u2kSu3KsE62kxFluAoFHl2vtvtRKu3CinhGITtnwSohe+4rt/nZnfyjM120FdF4B8Nk4eDRdhIwSwYQ7ZRcBJnEsGfvRE8jmtFfd7hZ1OUNUXPWayegJH9TMkLViFgt21pMQVZgXbG27ch1AEEzKYM7tYD2oBYpVv7JD7SgyBpSp8Dn0V44vLUuWj25sdni5T+ntDalXcCA1uniDSjZNHUuZSXa7g4KOkYXARETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are three ways we forget, and how does each of these happen?

(1) Encoding failure: Unattended information never entered our memory system. (2) Storage decay: Information fades from our memory. (3) Retrieval failure: We cannot access stored information accurately, sometimes due to interference or motivated forgetting.

Memory Construction Errors

reconsolidation a process in which previously stored memories, when retrieved, are potentially altered before being stored again.

8-

Memory is not precise. Like scientists who infer a dinosaur’s appearance from its remains, we infer our past from stored information plus what we later imagined, expected, saw, and heard. We don’t just retrieve memories, we reweave them. Like Wikipedia pages, memories can be continuously revised. When we “replay” a memory, we often replace the original with a slightly modified version (Hardt et al., 2010). (Memory researchers call this reconsolidation.) So, in a sense, said Joseph LeDoux (2009), “your memory is only as good as your last memory. The fewer times you use it, the more pristine it is.” This means that, to some degree, “all memory is false” (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009).

Despite knowing all this, I [DM] recently rewrote my own past. It happened at an international conference, where memory researcher Elizabeth Loftus (2012) was demonstrating how memory works. Loftus showed us a handful of individual faces that we were later to identify, as if in a police lineup. Later, she showed us some pairs of faces, one face we had seen earlier and one we had not, and asked us to identify the one we had seen. But one pair she had slipped in included two new faces, one of which was rather like a face we had seen earlier. Most of us understandably but wrongly identified this face as one we had previously seen. To climax the demonstration, when she showed us the originally seen face and the previously chosen wrong face, most of us picked the wrong face! As a result of our memory reconsolidation, we—

344

Clinical researchers are experimenting with people’s memory reconsolidation. They have people recall a traumatic or negative experience, then disrupt the reconsolidation of that memory with a drug or brief, painless electroconvulsive shock (Kroes et al., 2014; Lonergan, 2013). If, indeed, it becomes possible to erase your memory for a specific traumatic experience—

Misinformation and Imagination Effects

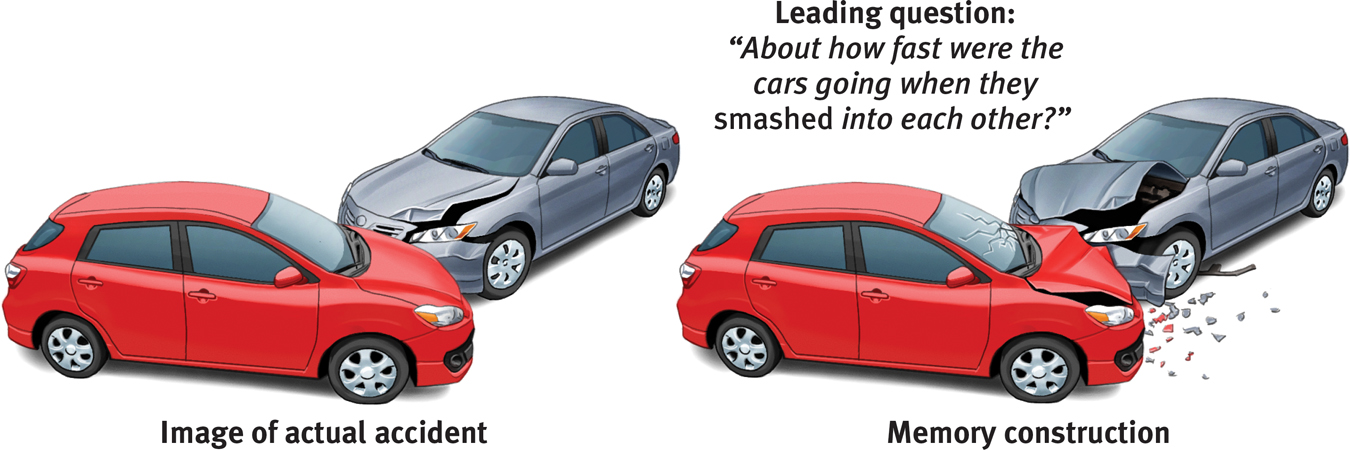

In more than 200 experiments involving more than 20,000 people, Loftus has shown how eyewitnesses reconstruct their memories after a crime or an accident. In one experiment, two groups of people watched a film clip of a traffic accident and then answered questions about what they had seen (Loftus & Palmer, 1974). Those asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?” gave higher speed estimates than those asked, “About how fast were the cars going when they hit each other?” A week later, when asked whether they recalled seeing any broken glass, people who had heard smashed were more than twice as likely to report seeing glass fragments (FIGURE 8.23). In fact, the clip showed no broken glass.

Figure 8.23

Figure 8.23Memory construction In this experiment, people viewed a film clip of a car accident (left). Those who later were asked a leading question recalled a more serious accident than they had witnessed (Loftus & Palmer, 1974).

misinformation effect when misleading information has corrupted one’s memory of an event.

In many follow-

So powerful is the misinformation effect that it can influence later attitudes and behaviors (Bernstein & Loftus, 2009). One experiment falsely suggested to some Dutch university students that, as children, they became ill after eating spoiled egg salad (Geraerts et al., 2008). After absorbing that suggestion, they were less likely to eat egg salad sandwiches, both immediately and four months later.

“Memory is insubstantial. Things keep replacing it. Your batch of snapshots will both fix and ruin your memory…. You can’t remember anything from your trip except the wretched collection of snapshots.”

Annie Dillard, “To Fashion a Text,” 1988

Because the misinformation effect happens outside our awareness, it is nearly impossible to sift the suggested ideas out of the larger pool of real memories (Schooler et al., 1986). Perhaps you can recall describing a childhood experience to a friend and filling in memory gaps with reasonable guesses and assumptions. We all do it, and after more retellings, those guessed details—

Even repeatedly imagining nonexistent actions and events can create false memories. American and British university students were asked to imagine certain childhood events, such as breaking a window with their hand or having a skin sample removed from a finger. One in four of them later recalled the imagined event as something that had really happened (Garry et al., 1996; Mazzoni & Memon, 2003).

345

Digitally altered photos have also produced this imagination inflation. In experiments, researchers have altered photos from a family album to show some family members taking a hot air balloon ride. After viewing these photos (rather than photos showing just the balloon), children reported more false memories and indicated high confidence in those memories. When interviewed several days later, they reported even richer details of their false memories (Strange et al., 2008; Wade et al., 2002).

Misinformation and imagination effects occur partly because visualizing something and actually perceiving it activate similar brain areas (Gonsalves et al., 2004). Imagined events also later seem more familiar, and familiar things seem more real. The more vividly we can imagine things, the more likely they are to become memories (Loftus, 2001; Porter et al., 2000).

In the discussion of mnemonics, we gave you six words and told you we would quiz you about them later. How many of these words can you now recall? Of these, how many are high-

Bicycle, void, cigarette, inherent, fire, process

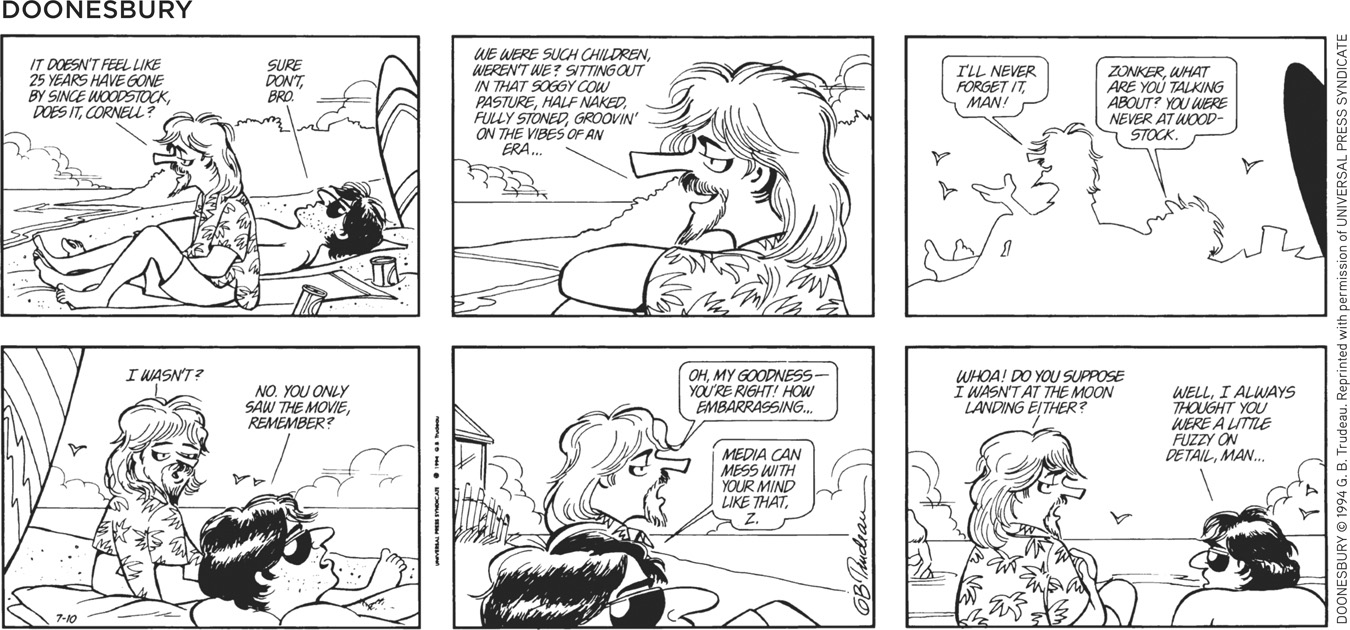

In British and Canadian university surveys, nearly one-

“It isn’t so astonishing, the number of things I can remember, as the number of things I can remember that aren’t so.”

Author Mark Twain (1835–1910)

source amnesia attributing to the wrong source an event we have experienced, heard about, read about, or imagined. (Also called source misattribution.) Source amnesia, along with the misinformation effect, is at the heart of many false memories.

346

Source Amnesia

déjà vu that eerie sense that “I’ve experienced this before.” Cues from the current situation may unconsciously trigger retrieval of an earlier experience.

Among the frailest parts of a memory is its source. We may recognize someone but have no idea where we have seen the person. We may dream an event and later be unsure whether it really happened. We may misrecall how we learned about something (Henkel et al., 2000). Psychologists are not immune to the process. Famed child psychologist Jean Piaget was startled as an adult to learn that a vivid, detailed memory from his childhood—

Debra Poole and Stephen Lindsay (1995, 2001, 2002) demonstrated source amnesia among preschoolers. They had the children interact with “Mr. Science,” who engaged them in activities such as blowing up a balloon with baking soda and vinegar. Three months later, on three successive days, their parents read them a story describing some things the children had experienced with Mr. Science and some they had not. When a new interviewer asked what Mr. Science had done with them—

Source amnesia also helps explain déjà vu (French for “already seen”). Two-

Alan Brown and Elizabeth Marsh (2009) devised an intriguing way to induce déjà vu in the laboratory. They invited participants to view symbols on a computer screen and to report whether they had ever seen them before. What the viewers didn’t know was that these symbols had earlier been subliminally flashed on the screen, too briefly for conscious awareness. The result? Half the participants reported experiencing déjà vu—

“Do you ever get that strange feeling of vujà dé? Not déjà vu; vujà dé. It’s the distinct sense that, somehow, something just happened that has never happened before. Nothing seems familiar. And then suddenly the feeling is gone. Vujà dé.”

Comedian George Carlin (1937–2008), in Funny Times, December 2001

The key to déjà vu seems to be familiarity with a stimulus without a clear idea of where we encountered it before (Cleary, 2008). Normally, we experience a feeling of familiarity (thanks to temporal lobe processing) before we consciously remember details (thanks to hippocampus and frontal lobe processing). When these functions (and brain regions) are out of sync, we may experience a feeling of familiarity without conscious recall. Our amazing brains try to make sense of such an improbable situation, and we get an eerie feeling that we’re reliving some earlier part of our life. After all, the situation is familiar, even though we have no idea why. Our source amnesia forces us to do our best to make sense of an odd moment.

Discerning True and False Memories

Because memory is reconstruction as well as reproduction, we can’t be sure whether a memory is real by how real it feels. Much as perceptual illusions may seem like real perceptions, unreal memories feel like real memories.

347

False memories can be persistent. Imagine that we were to read aloud a list of words such as candy, sugar, honey, and taste. Later, we ask you to recognize the presented words from a larger list. If you are at all like the people tested by Henry Roediger and Kathleen McDermott (1995), you would err three out of four times—

To participate in a simulated experiment on false memory formation, and to review related research, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Can You Trust Your Memory?

To participate in a simulated experiment on false memory formation, and to review related research, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Can You Trust Your Memory?

Memory construction helps explain why about 75 percent of 301 convicts exonerated by later DNA testing had been misjudged based on faulty eyewitness identification (Lilienfeld & Byron, 2013). It explains why “hypnotically refreshed” memories of crimes so easily incorporate errors, some of which originate with the hypnotist’s leading questions (“Did you hear loud noises?”). It explains why dating partners who fell in love have overestimated their first impressions of one another (“It was love at first sight”), while those who broke up underestimated their earlier liking (“We never really clicked”) (McFarland & Ross, 1987). And it explains why people asked how they felt 10 years ago about marijuana or gender issues recalled attitudes closer to their current views than to the views they had actually reported a decade earlier (Markus, 1986). How people feel today tends to be how they recall they have always felt (Mazzoni & Vannucci, 2007).

For a 5-

For a 5-

One research team interviewed 73 ninth-

Children’s Eyewitness Recall

8-

If memories can be sincere, yet sincerely wrong, might children’s recollections of sexual abuse be prone to error? “It would be truly awful to ever lose sight of the enormity of child abuse,” observed Stephen Ceci (1993). Yet Ceci and Maggie Bruck’s (1993, 1995) studies of children’s memories have made them aware of how easily children’s memories can be molded. For example, they asked 3-

In other experiments, the researchers studied the effect of suggestive interviewing techniques (Bruck & Ceci, 1999, 2004). In one study, children chose a card from a deck of possible happenings, and an adult then read the card to them. For example, “Think real hard, and tell me if this ever happened to you. Can you remember going to the hospital with a mousetrap on your finger?” In interviews, the same adult repeatedly asked children to think about several real and fictitious events. After 10 weeks of this, a new adult asked the same question. The stunning result: 58 percent of preschoolers produced false (often vivid) stories regarding one or more events they had never experienced (Ceci et al., 1994). Here’s one:

My brother Colin was trying to get Blowtorch [an action figure] from me, and I wouldn’t let him take it from me, so he pushed me into the wood pile where the mousetrap was. And then my finger got caught in it. And then we went to the hospital, and my mommy, daddy, and Colin drove me there, to the hospital in our van, because it was far away. And the doctor put a bandage on this finger.

348

Consider how researchers have studied these issues with LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If People’s Memories Are Accurate?

Given such detailed stories, professional psychologists who specialize in interviewing children could not reliably separate the real memories from the false ones. Nor could the children themselves. The above child, reminded that his parents had told him several times that the mousetrap incident never happened—

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

Repressed or Constructed Memories of Abuse?

8-

There are two tragedies related to adult recollections of child abuse. One happens when people don’t believe abuse survivors who tell their secret. The other happens when innocent people are falsely accused. What, then, shall we say about clinicians who have guided people in “recovering” childhood abuse memories? Were these well-

The research on source amnesia and the misinformation effect raises concerns about therapist-

Critics are not questioning the professionalism of most therapists. Nor are they questioning the accusers’ sincerity; even if false, their memories are heartfelt. Critics’ charges are specifically directed against clinicians who have used “memory work” techniques, such as “guided imagery,” hypnosis, and dream analysis. “Thousands of families were cruelly ripped apart,” with “previously loving adult daughters” suddenly accusing fathers (Gardner, 2006). Irate clinicians countered that those who argue that recovered memories of abuse never happen are adding to abused people’s trauma and playing into the hands of child molesters.

Is there a sensible common ground that might resolve psychology’s “memory war”—which exposed researcher and expert witness Elizabeth Loftus (2011) to “relentless vitriol and harrassment”? Professional organizations (the American Medical, American Psychological, and American Psychiatric Associations; the Australian Psychological Society; the British Psychological Society; and the Canadian Psychiatric Association) have convened study panels and issued public statements, and greater agreement is emerging (Patihis et al., 2014). Those committed to protecting abused children and those committed to protecting wrongly accused adults have agreed on the following:

- Sexual abuse happens. And it happens more often than we once supposed. Although sexual abuse can leave its victims at risk for problems ranging from sexual dysfunction to depression (Freyd et al., 2007), there is no characteristic “survivor syndrome”—no group of symptoms that lets us spot victims of sexual abuse (Kendall-

Tackett et al., 1993). - Injustice happens. Some innocent people have been falsely convicted. And some guilty people have evaded responsibility by casting doubt on their truth-

telling accusers. - Forgetting happens. Many of those actually abused were either very young when abused or may not have understood the meaning of their experience—

circumstances under which forgetting is common. Forgetting isolated past events, both negative and positive, is an ordinary part of everyday life. - Recovered memories are commonplace. Cued by a remark or an experience, we all recover memories of long-

forgotten events, both pleasant and unpleasant. What psychologists debate is twofold: Does the unconscious mind sometimes forcibly repress painful experiences? If so, can these experiences be retrieved by certain therapist- aided techniques? (Memories that surface naturally are more likely to be verified [Geraerts et al., 2007].) - Memories of events before age 3 are unreliable. We cannot reliably recall happenings from our first three years. As noted earlier, this infantile amnesia happens because our brain pathways have not yet developed enough to form the kinds of memories we will form later in life. Most psychologists—

including most clinical and counseling psychologists— therefore doubt “recovered” memories of abuse during infancy (Gore- Felton et al., 2000; Knapp & VandeCreek, 2000). The older a child was when suffering sexual abuse, and the more severe the abuse, the more likely it is to be remembered (Goodman et al., 2003). - Memories “recovered” under hypnosis or the influence of drugs are especially unreliable. Under hypnosis, people will incorporate all kinds of suggestions into their memories, even memories of “past lives.”

- Memories, whether real or false, can be emotionally upsetting. Both the accuser and the accused may suffer when what was born of mere suggestion becomes, like an actual trauma, a stinging memory that drives bodily stress (McNally, 2003, 2007). Some people knocked unconscious in unremembered accidents know this all too well. They have later developed stress disorders after being haunted by memories they constructed from photos, news reports, and friends’ accounts (Bryant, 2001).

The debate over repression and childhood sexual abuse, like many other scientific debates, has stimulated new research and new theories. Richard McNally and Elke Geraerts (2009; McNally, 2012) contend that victims of most childhood sexual abuse do not repress their abuse; rather, they simply stop devoting thought and emotion to it. McNally and Geraerts believe this letting go of the memory is most likely when

- the experience, when it occurred, was strange, uncomfortable, and confusing, rather than severely traumatic.

- the abuse happened once or only a few times.

- victims have not spent time thinking about the abuse, either because of their own resilience or because no reminders are available.

“When memories are ‘recovered’ after long periods of amnesia, particularly when extraordinary means were used to secure the recovery of memory, there is a high probability that the memories are false.”

Royal College of Psychiatrists Working Group on Reported Recovered Memories of Child Sexual Abuse (Brandon et al., 1998)

McNally and Geraerts agree that victims do sometimes accurately and spontaneously recall memories of childhood abuse. But these memories usually occur outside of therapy. Moreover, people who recall abuse spontaneously rarely form false memories when in a lab setting. Conversely, those who form memories of abuse during suggestive therapy tend to have vivid imaginations and score high on false-

So, does repression of threatening memories ever occur? Or is this concept—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Imagine being a jury member in a trial for a parent accused of sexual abuse based on a recovered memory. What insights from memory research should you offer the jury?

It will be important to remember the key points agreed upon by most researchers and professional associations: Sexual abuse, injustice, forgetting, and memory construction all happen; recovered memories are common; memories from before age 3 are unreliable; memories claimed to be recovered through hypnosis or drug influence are especially unreliable; and memories, whether real or false, can be emotionally upsetting.

349

Children can, however, be accurate eyewitnesses. When questioned about their experiences in neutral words they understood, children often accurately recalled what happened and who did it (Goodman, 2006; Howe, 1997; Pipe, 1996). When interviewers used less suggestive, more effective techniques, even 4-

Like children (whose frontal lobes have not fully matured), older adults—

Question

PMstWn2U7N6BGI1Y1OkcBklktgm7wtBftfp18SZlnk1dAuFigwekCcnjFKhMR4GhzuVoSjpiAO11aZZT1X8Mwb0Eb1MxSmgxaejpoGJ2q45J2IhlnYEFUlsQl2rKEwdc2cluOG/oyX420j8QJtizJUlJqELDVX1ocpnfblUe7GSS26GwLUCR1uqvdKJVeHYr9fMbBDaAgTynTOHGaayOWAxvpJEk+0EGl9/fAbGSuus=350

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What—

given the commonality of source amnesia— might life be like if we remembered all our waking experiences and all our dreams?

Real experiences would be confused with those we dreamed. When meeting someone, we might therefore be unsure whether we were reacting to something they previously did or to something we dreamed they did.

Improving Memory

8-

Biology’s findings benefit medicine. Botany’s findings benefit agriculture. So, too, can psychology’s research on memory benefit education. Here, for easy reference, is a summary of some research-

- Rehearse repeatedly. To master material, use distributed (spaced) practice. To learn a concept, give yourself many separate study sessions. Take advantage of life’s little intervals—

riding a bus, walking across campus, waiting for class to start. New memories are weak; exercise them and they will strengthen. To memorize specific facts or figures, Thomas Landauer (2001) has advised, “rehearse the name or number you are trying to memorize, wait a few seconds, rehearse again, wait a little longer, rehearse again, then wait longer still and rehearse yet again. The waits should be as long as possible without losing the information.” Reading complex material with minimal rehearsal yields little retention. Rehearsal and critical reflection help more. As the testing effect has shown, it pays to study actively. Taking lecture notes in longhand, which requires summarizing material in your own words, leads to better retention than does verbatim laptop note taking. “The pen is mightier than the keyboard,” note researchers Pam Mueller and Daniel Oppenheimer (2014).  Thinking and memory Actively thinking as we read, by rehearsing and relating ideas, and by making the material personally meaningful, yields the best retention.

Thinking and memory Actively thinking as we read, by rehearsing and relating ideas, and by making the material personally meaningful, yields the best retention. - Make the material meaningful. You can build a network of retrieval cues by taking text and class notes in your own words. Apply the concepts to your own life. Form images. Understand and organize information. Relate the material to what you already know or have experienced. As William James (1890) suggested, “Knit each new thing on to some acquisition already there.” Restate concepts in your own words. Mindlessly repeating someone else’s words won’t supply many retrieval cues. On an exam, you may find yourself stuck when a question uses phrasing different from the words you memorized.

- Activate retrieval cues. Mentally re-

create the situation and the mood in which your original learning occurred. Jog your memory by allowing one thought to cue the next. - Use mnemonic devices. Associate items with peg words to harness visual imagery skills to illustrate in your mind’s eye what is to be remembered (“one is a bun, two is a shoe”). Make up a story that incorporates vivid images of the items. Chunk information into acronyms. Create rhythmic rhymes (“i before e, except after c”).

- Minimize interference. Study before sleep. Do not schedule back-

to- back study times for topics that are likely to interfere with each other, such as Spanish and French. - Sleep more. During sleep, the brain reorganizes and consolidates information for long-

term memory. Sleep deprivation disrupts this process. Even 10 minutes of waking rest enhances memory of what we have read (Dewar et al., 2012). So, after a period of hard study, perhaps just sit or lie down for a few minutes before tackling the next subject. - Test your own knowledge, both to rehearse it and to find out what you don’t yet know. Don’t be lulled into overconfidence by your ability to recognize information. Test your recall using the periodic Retrieval Practice items, the numbered Learning Objective questions in the Review sections, and the self-

test questions at the end of each chapter. Outline sections using a blank page. Define the terms and concepts listed at each section’s end before turning back to their definitions. Take practice tests; the websites and study guides that accompany many texts, including this one, are a good source for such tests.

351

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are the recommended memory strategies you just read about?

Rehearse repeatedly to boost long-

352