9.2 Language and Thought

language our spoken, written, or signed words and the ways we combine them to communicate meaning.

Imagine an alien species that could pass thoughts from one head to another merely by pulsating air molecules in the space between them. Perhaps these weird creatures could inhabit a future science fiction movie?

Actually, we are those creatures. When we speak, our brain and voice apparatus conjure up air pressure waves that we send banging against another’s eardrum—

But language is more than vibrating air. As I [DM] create this paragraph, my fingers on a keyboard generate electronic binary numbers that are translated into the squiggles in front of you. When transmitted by reflected light rays into your retina, those squiggles trigger formless nerve impulses that project to several areas of your brain, which integrate the information, compare it to stored information, and decode meaning. Thanks to language, information is moving from my mind to yours. Monkeys mostly know what they see. Thanks to language (spoken, written, or signed), we comprehend much that we’ve never seen and that our distant ancestors never knew. Today, notes Daniel Gilbert (2006), the average taxi driver in Pittsburgh “knows more about the universe than did Galileo, Aristotle, Leonardo, or any of those other guys who were so smart they only needed one name.”

To Pinker (1990), language is “the jewel in the crown of cognition.” If you were able to retain only one cognitive ability, make it language, suggests researcher Lera Boroditsky (2009). Without sight or hearing, you could still have friends, family, and a job. But without language, could you have these things? “Language is so fundamental to our experience, so deeply a part of being human, that it’s hard to imagine life without it.”

Language Structure

9-

Consider how we might go about inventing a language. For a spoken language, we would need three building blocks:

- Phonemes are the smallest distinctive sound units in a language. To say bat, English speakers utter the phonemes b, a, and t. (Phonemes aren’t the same as letters. That also has three phonemes—

th, a, and t.) Linguists surveying nearly 500 languages have identified 869 different phonemes in human speech, but no language uses all of them (Holt, 2002; Maddieson, 1984). English uses about 40; other languages use anywhere from half to more than twice that many. As a general rule, consonant phonemes carry more information than do vowel phonemes. The treth ef thes stetement shed be evedent frem thes bref demenstretien. - Morphemes are the smallest language units that carry meaning. In English, a few morphemes are also phonemes—

the article a, for instance. But most morphemes combine two or more phonemes. Some, like bat or gentle are words. Others— like the prefix pre- in preview or the suffix -ed in adapted—are parts of words. - Grammar is the system of rules that enables us to communicate with one another. Grammatical rules guide us in deriving meaning from sounds (semantics) and in ordering words into sentences (syntax).

phoneme in a language, the smallest distinctive sound unit.

morpheme in a language, the smallest unit that carries meaning; may be a word or a part of a word (such as a prefix).

grammar in a language, a system of rules that enables us to communicate with and understand others. In a given language, semantics is the set of rules for deriving meaning from sounds, and syntax is the set of rules for combining words into grammatically sensible sentences.

371

Like life constructed from the genetic code’s simple alphabet, language is complexity built of simplicity. In English, for example, 40 or so phonemes can be combined to form more than 100,000 morphemes, which alone or in combination produce the 616,500 word forms in the Oxford English Dictionary. Using those words, we can then create an infinite number of sentences, most of which (like this one) are original. I know that you can know why I worry that you think this sentence is starting to get too complex, but that complexity—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How many morphemes are in the word cats? How many phonemes?

Two morphemes—

Language Development

9-

Make a quick guess: How many words of your native language did you learn between your first birthday and your high school graduation? Although you use only 150 words for about half of what you say, you probably learned about 60,000 words (Bloom, 2000; McMurray, 2007). That averages (after age 2) to nearly 3500 words each year, or nearly 10 each day! How you did it—

Could you even state your language’s rules of syntax (the correct way to string words together to form sentences)? Most of us cannot. Yet before you were able to add 2 + 2, you were creating your own original and grammatically appropriate sentences. As a preschooler, you comprehended and spoke with a facility that puts to shame college students struggling to learn a foreign language.

We humans have an astonishing facility for language. With remarkable efficiency, we sample tens of thousands of words in our memory, effortlessly assemble them with near-

When Do We Learn Language?

Receptive Language Children’s language development moves from simplicity to complexity. Infants start without language (in fantis means “not speaking”). Yet by 4 months of age, babies can recognize differences in speech sounds (Stager & Werker, 1997). They can also read lips: They prefer to look at a face that matches a sound, so we know they can recognize that ah comes from wide open lips and ee from a mouth with corners pulled back (Kuhl & Meltzoff, 1982). This marks the beginning of the development of babies’ receptive language, their ability to understand what is said to and about them. Infants’ language comprehension greatly outpaces their language production. Even at six months, long before speaking, many infants recognize object names (Ber-

babbling stage beginning at about 4 months, the stage of speech development in which the infant spontaneously utters various sounds at first unrelated to the household language.

372

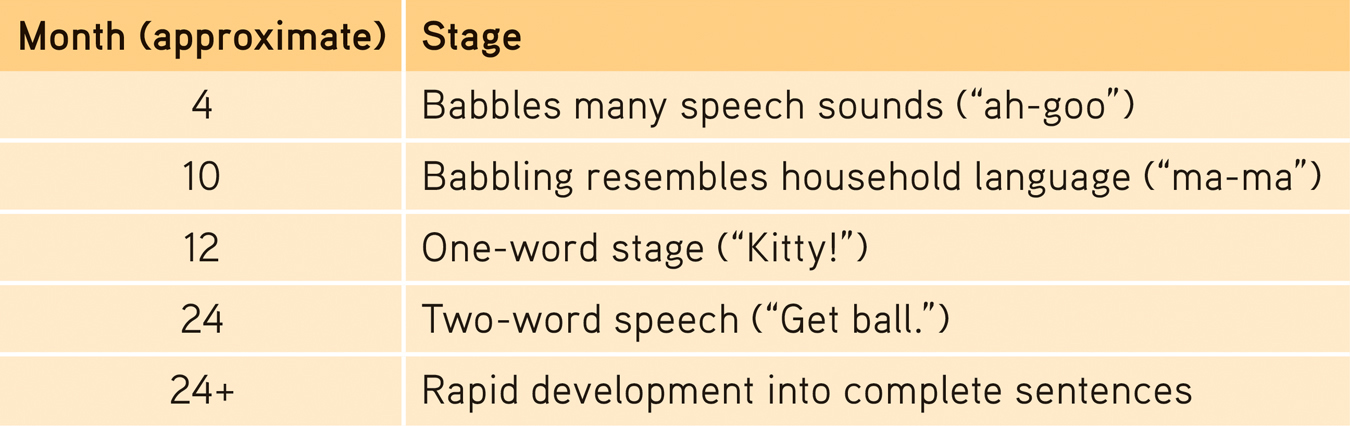

Productive Language Long after the beginnings of receptive language, babies’ productive language, their ability to produce words, matures. They recognize noun–

Before nurture molds babies’ speech, nature enables a wide range of possible sounds in the babbling stage, beginning at around 4 months. Many of these spontaneously uttered sounds are consonant-

one-

two-

By about 10 months old, infants’ babbling has changed so that a trained ear can identify the household language (de Boysson-

Around their first birthday, most children enter the one-

At about 18 months, children’s word learning explodes from about a word per week to a word per day. By their second birthday, most have entered the two-

TABLE 9.1

TABLE 9.1Summary of Language Development

telegraphic speech early speech stage in which a child speaks like a telegram—

Moving out of the two-

373

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the difference between receptive and productive language, and when do children normally hit these milestones in language development?

Infants normally start developing receptive language skills (ability to understand what is said to and about them) around 4 months of age. Then, starting with babbling at 4 months and beyond, infants normally start building productive language skills (ability to produce sounds and eventually words).

Explaining Language Development

The world’s 6000+ or so languages are structurally very diverse (Evans & Levinson, 2009). Linguist Noam Chomsky has argued that all languages nonetheless share some basic elements, which he calls universal grammar. All human languages, for example, have nouns, verbs, and adjectives as grammatical building blocks. Moreover, said Chomsky, we humans are born with a built-

We are not born with a built-

Statistical Learning When adults listen to an unfamiliar language, the syllables all run together. A young Sudanese couple new to North America and unfamiliar with English might, for example, hear United Nations as “Uneye Tednay Shuns.” Their 7-

In further testimony to infants’ surprising knack for soaking up language, research shows that 7-

374

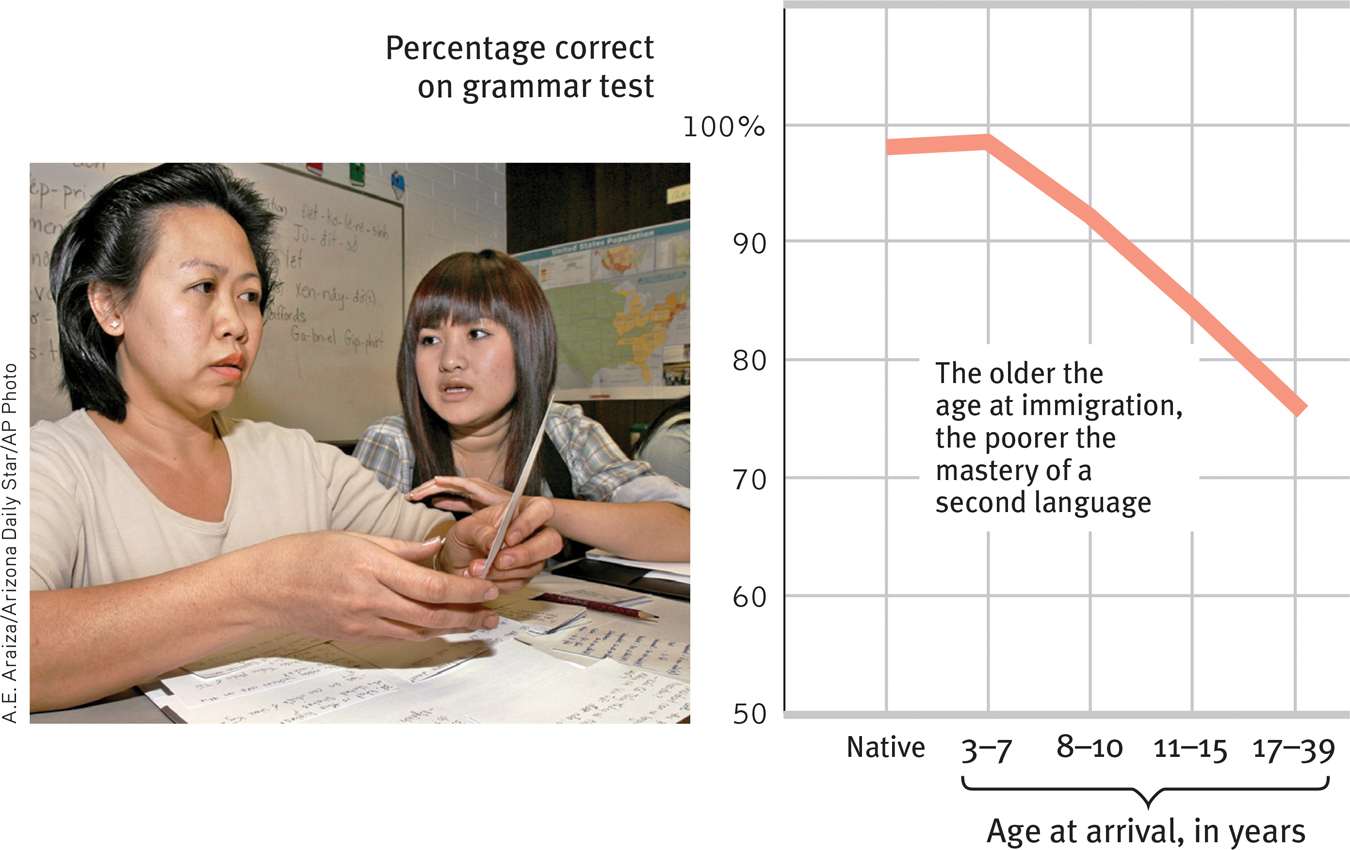

Critical Periods Could we train adults to perform this same feat of statistical analysis later in the human life span? Many researchers believe not. Childhood seems to represent a critical (or “sensitive”) period for mastering certain aspects of language before the language-

Figure 9.9

Figure 9.9Our ability to learn a new language diminishes with age Ten years after coming to the United States, Asian immigrants took an English grammar test. Although there is no sharply defined critical period for second language learning, those who arrived before age 8 understood American English grammar as well as native speakers did. Those who arrived later did not. (Data from Johnson & Newport, 1991.)

The window on language learning closes gradually in early childhood. Later-

“Childhood is the time for language, no doubt about it. Young children, the younger the better, are good at it; it is child’s play. It is a onetime gift to the species.”

Lewis Thomas, The Fragile Species, 1992

Deafness and Language Development

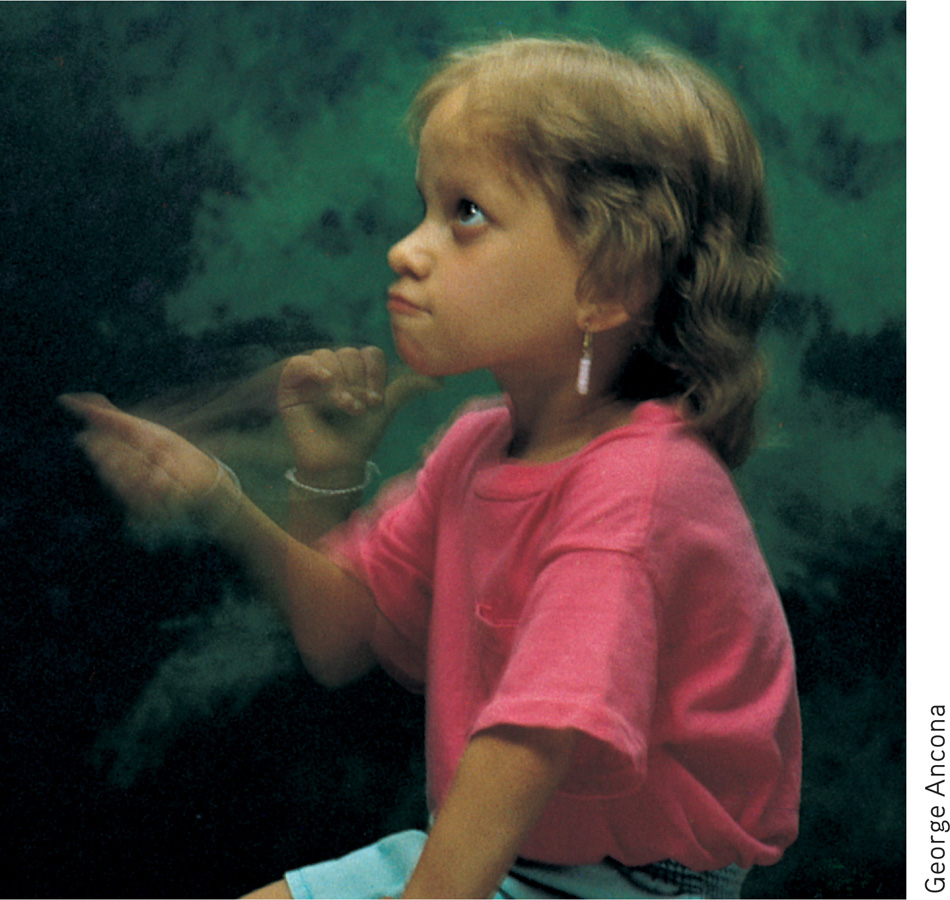

The impact of early experiences is evident in language learning in prelingually (before learning language) deaf5 children born to hearing-

“Children can learn multiple languages without an accent and with good grammar, if they are exposed to the language before puberty. But after puberty, it’s very difficult to learn a second language so well. Similarly, when I first went to Japan, I was told not even to bother trying to bow, that there were something like a dozen different bows and I was always going to ‘bow with an accent’.”

Psychologist Stephen M. Kosslyn, “The World in the Brain,” 2008

More than 90 percent of all deaf children are born to hearing parents. Most of these parents want their children to experience their world of sound and talk. Cochlear implants enable this by converting sounds into electrical signals and stimulating the auditory nerve by means of electrodes threaded into the child’s cochlea. But if an implant is to help children become proficient in oral communication, parents cannot delay the surgery until their child reaches the age of consent. Giving cochlear implants to children is hotly debated. Deaf culture advocates object to giving implants to children who were deaf prelingually. The National Association of the Deaf, for example, argues that deafness is not a disability because native signers are not linguistically disabled. More than five decades ago, Gallaudet University linguist William Stokoe (1960) showed that sign is a complete language with its own grammar, syntax, and meanings.

375

Deaf culture advocates sometimes further contend that deafness could as well be considered “vision enhancement” as “hearing impairment.” Close your eyes and immediately you, too, will notice your attention being drawn to your other senses. In one experiment, people who had spent 90 minutes sitting quietly blindfolded became more accurate in their location of sounds (Lewald, 2007). When kissing, lovers minimize distraction and increase sensitivity by closing their eyes.

People who lose one channel of sensation compensate with a slight enhancement of their other sensory abilities (Backman & Dixon, 1992; Levy & Langer, 1992). Blind musicians are more likely than sighted ones to develop perfect pitch (Hamilton, 2000). Blind people are also more accurate than sighted people at locating a sound source with one ear plugged (Gougoux et al., 2005; Lessard et al., 1998). And when reading Braille—

In deaf cats, brain areas normally used for hearing donate themselves to the visual system (Lomber et al., 2010). So, too, in people who have been deaf from birth: They exhibit enhanced attention to their peripheral vision (Bavelier et al., 2006). Their auditory cortex, starved for sensory input, remains largely intact but becomes responsive to touch and to visual input (Karns et al., 2012). Once repurposed, the auditory cortex becomes less available for hearing—

Living in a Silent World Worldwide, 360 million people live with disabling hearing loss (WHO, 2013). Some are profoundly deaf; others (more men than women) have hearing loss (Agrawal et al., 2008). Some were deaf prelingually; others have known the hearing world. Some sign and identify with the language-

The challenges of life without hearing may be greatest for children. Unable to communicate in customary ways, signing playmates may struggle to coordinate their play with speaking playmates. School achievement may also suffer; academic subjects are rooted in spoken languages. Adolescents may feel socially excluded, with a resulting low self-

Adults whose hearing becomes impaired later in life also face challenges. When older people with hearing loss must expend effort to hear words, they have less remaining cognitive capacity available to remember and comprehend them (Wingfield et al., 2005). In several studies, people with hearing loss, especially those not wearing hearing aids, have reported feeling sadder, being less socially engaged, and more often experiencing others’ irritation (Chisolm et al., 2007; Fellinger et al., 2007; Kashubeck-

376

I [DM] understand. My mother, with whom we communicated by writing notes on an erasable “magic pad,” spent her last dozen years in an utterly silent world, largely withdrawn from the stress and strain of trying to interact with people outside a small circle of family and old friends. With my own hearing declining on a trajectory toward hers, I find myself sitting front and center at plays and meetings, seeking quiet corners in restaurants, and asking my wife to make necessary calls to friends whose accents differ from ours. I do benefit from cool technology (see www.hearingloop.org) that, at the press of a button, can transform my hearing aids into in-

As she aged, my mother came to feel that seeking social interaction was simply not worth the effort. I share newspaper columnist Kisor’s belief that communication is worth the effort (p. 246): “So, … I will grit my teeth and plunge ahead.” To reach out, to connect, to communicate with others, even across a chasm of silence, is to affirm our humanity as social creatures.

Question

To2jDdIhWPGopiLM0v4Gz45Q6MMu7N1uxRbxeoS8L5kv/EAd5vn93yLaikDii4I18g0z2Qrby8A3DEbCislVkSuHYr9Z4v2yUdEIF0R35xTuU6rq1sBNKdJ9/YDSWo+Z6lsouovYfGqfVb4e6Uu6GgZ2P/9Ck9595YgOepVwkKdMpnTvFUq0IHRednsThQuOtaptBysvXis4umHvZGOQgeGGNcfYEqfnT/+5N6IjJTEHkaQDzoBaCD11N2nToLUiXAUCOwGKOsaUzfjB88WH171TYHpTdX9nJKNjncGCg7WjiJmdGim5QKwSvRJHQ8aN5JuGflYORt8GEvjmmcu16UVHGt6c/en1M3oytt2OVsTnaFs44rPcirGLbfNm8nwAkSmiJ2d5rq6v+RkoRETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What was the premise of researcher Noam Chomsky’s work in language development?

Chomsky maintained that all languages share a universal grammar, and humans are biologically predisposed to learn the grammar rules of language.

- Why is it so difficult to learn a new language in adulthood?

Our brain’s critical period for language learning is in childhood, when we can absorb language structure almost effortlessly. As we move past that stage in our brain’s development, our ability to learn a new language diminishes dramatically.

The Brain and Language

aphasia impairment of language, usually caused by left hemisphere damage either to Broca’s area (impairing speaking) or to Wernicke’s area (impairing understanding).

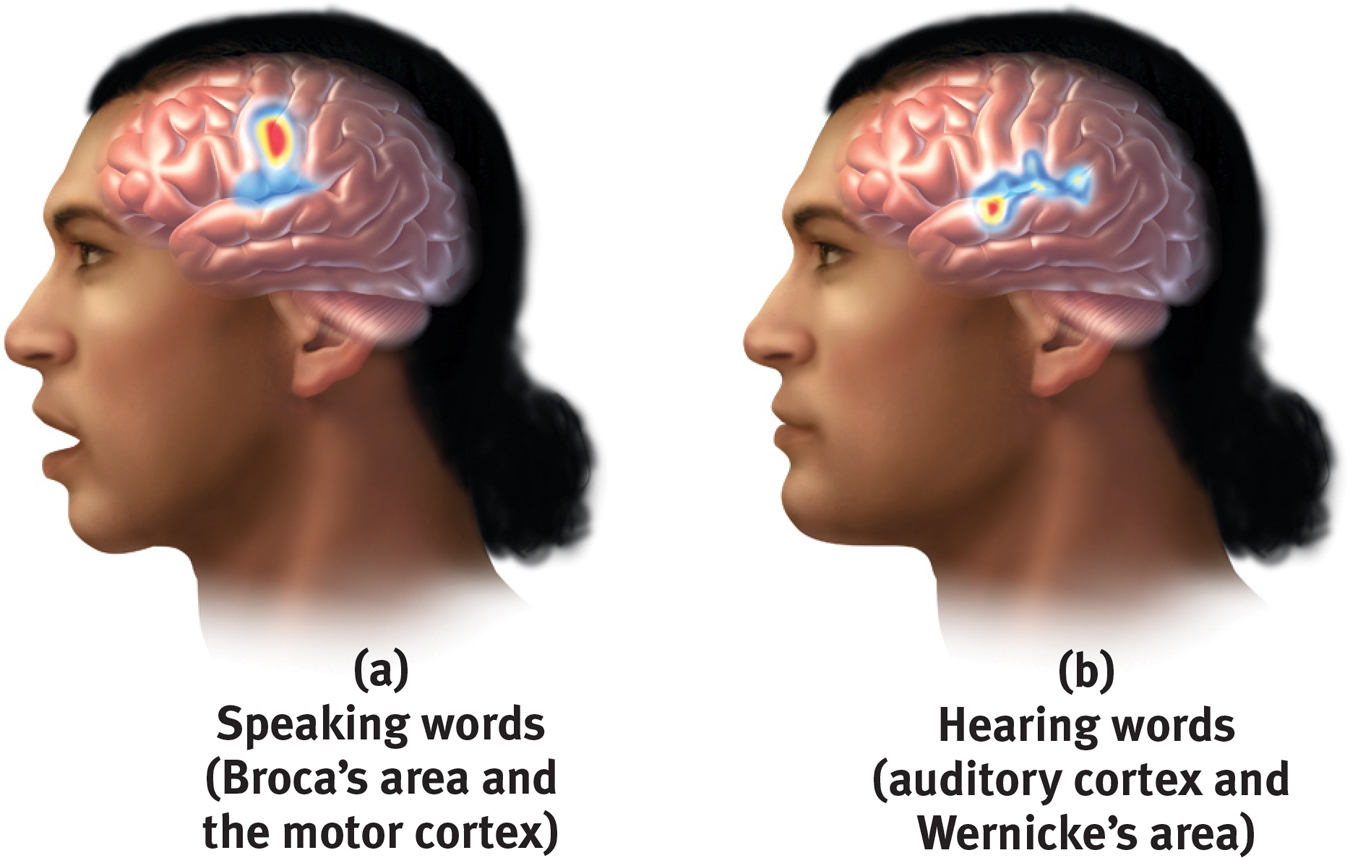

Broca’s area controls language expression—

9-

We think of speaking and reading, or writing and reading, or singing and speaking as merely different examples of the same general ability—

To review research on left and right hemisphere language processing—

To review research on left and right hemisphere language processing—

Wernicke’s area controls language reception—

Indeed, in 1865, French physician Paul Broca reported that after damage to an area of the left frontal lobe (later called Broca’s area) a person would struggle to speak words while still being able to sing familiar songs and comprehend speech.

In 1874, German investigator Carl Wernicke discovered that after damage to an area of the left temporal lobe (Wernicke’s area) people could speak only meaningless words. Asked to describe a picture that showed two boys stealing cookies behind a woman’s back, one patient responded: “Mother is away her working her work to get her better, but when she’s looking the two boys looking the other part. She’s working another time” (Geschwind, 1979). Damage to Wernicke’s area also disrupts understanding.

“It is the way systems interact and have a dynamic interdependence that is—

Simon Conway Morris, “The Boyle Lecture,” 2005

Today’s neuroscience has confirmed brain activity in Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas during language processing (FIGURE 9.10). But language functions are distributed across other brain areas as well. Functional MRI scans show that different neural networks are activated by nouns and verbs (or objects and actions); by different vowels; and by reading stories of visual versus motor experiences (Shapiro et al., 2006; Speer et al., 2009). Different neural networks also enable one’s native language and a second language (Perani & Abutalebi, 2005).

Figure 9.10

Figure 9.10Brain activity when speaking and hearing words

377

The big point to remember: In processing language, as in other forms of information processing, the brain operates by dividing its mental functions—

Question

H92C/p/e0gVSSgc4ddVkVgWmdSLNlI92GMhYsoUvdrbrCEh9CxobL/PkMwEakaJdjg3d5NO7Fi0RKQJiiKCcwV17QFbAYi/n+5MhpVdNI0Eqezo+uMm/ltcTf+RIkbTUnILKNvVCanVBv9WuJAQ6yUhhn+rxRnaTNrNC19sMPnIdP1Svqri9FuOE2RE28JhEa1CQ8Qwvo6q/2HrQkhvabWDXP13KmKKSCmCHqa2KxT9HcsK8y859mgus9+PzFz1jTOjPtata1wp98RY2w025gN+7Cdm3o4CI5lILPnEpzWwo9ZZORETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- ______________ ______________ is the part of the brain that, if damaged, might impair your ability to speak words. Damage to ______________ ______________ might impair your ability to understand language.

Broca’s area; Wernicke’s area

Do Other Species Have Language?

9-

Humans have long and proudly proclaimed that language sets us above all other animals. “When we study human language,” asserted linguist Noam Chomsky (1972), “we are approaching what some might call the ‘human essence,’ the qualities of mind that are, so far as we know, unique [to humans].” Let’s see if research on animal language supports claims that humans, alone, have language.

Animals display impressive comprehension and communication. Vervet monkeys sound different alarm cries for different predators: a barking call for a leopard, a cough for an eagle, and a chuttering for a snake. Hearing the leopard alarm, other vervets climb the nearest tree. Hearing the eagle alarm, they rush into the bushes. Hearing the snake chutter, they stand up and scan the ground (Byrne, 1991). To indicate such things as a type of threat—

In the late 1960s, psychologists Allen Gardner and Beatrix Gardner (1969) built on chimpanzees’ natural tendencies for gestured communication by teaching sign language to a young chimpanzee named Washoe. After four years, Washoe could use 132 signs; by her life’s end in 2007, she was using more than 245 signs (Metzler, 2011; Sanz et al., 1998). Washoe, for example, signed “You me go out, please.” Some word combinations seemed creative—

378

- Ape vocabularies and sentences are simple, rather like those of a 2-

year- old child. And unlike speaking or signing children, apes gain their limited vocabularies only with great difficulty (Wynne, 2004, 2008). Saying that apes can learn language because they can sign words is like saying humans can fly because they can jump. - Chimpanzees can make signs or push buttons in sequence to get a reward. But pigeons, too, can peck a sequence of keys to get grain (Straub et al., 1979). The apes’ signing might be nothing more than aping their trainers’ signs and learning that certain arm movements produce rewards (Terrace, 1979).

- Studies of perceptual set (described in Chapter 6) show that when information is unclear, we tend to see what we want or expect to see. Interpreting chimpanzee signs as language may be little more than the trainers’ wishful thinking (Terrace, 1979). When Washoe signed water bird, she may have been separately naming water and bird.

- “Give orange me give eat orange me eat orange …” is a far cry from the exquisite syntax of a 3-

year- old (Anderson, 2004; Pinker, 1995). To the child, “You tickle” and “Tickle you” communicate different ideas. A chimpanzee, lacking human syntax, might use the same sequence of signs for both phrases.

Controversy can stimulate progress, and in this case, it triggered more evidence of chimpanzees’ abilities to think and communicate. One surprising finding was that Washoe trained her adopted son Loulis to use the signs she had learned. After her second infant died, Washoe became withdrawn when told, “Baby dead, baby gone, baby finished.” Two weeks later, researcher-

Even more stunning was a report that Kanzi, a bonobo with a reported 384-

379

So, how should we interpret these studies? Are humans the only language-

One thing is certain: Studies of animal language and thinking have moved psychologists toward a greater appreciation of other species, not only for our common traits but also for their own remarkable abilities. In the past, many psychologists doubted that other species could plan, form concepts, count, use tools, show compassion, or use language (Thorpe, 1974). Today, thanks to animal researchers, we know better. It’s true that humans alone are capable of complex sentences. Moreover, 2½-year-

Nevertheless, other species do exhibit insight, show family loyalty, communicate with one another, care for one another, and transmit cultural patterns across generations. Working out what this means for the moral rights of other animals is an unfinished task.

Question

Z7gOPVk2MbFc5lAgBPCBc2LnBP7kNEJJUminajsreFvkaaO0S8XUdOEebrK5IJb8tbcZNEMo7RBUcdE+Mtx4INKrqEer5ZF+BSoDitf2UnrbPXeoPeg3nMisqdmftF/1nqBzJeMkSjhGMyaO9fb/c9M/i3+KZ0qA7xEUReawEcSiLvalQjvU+8KksPbX31or9/25scBp0Zn+cr/GvJpXDKcV1sVwIIqJh8eWsqDOr1BQLbSgJjXMDnLz/XVuZhv5gYON5Q6LmghCO7yC+BVCzVIMwJjbVYX0 For examples of intelligent communication and problem solving among orangutans, elephants, and killer whales, watch LaunchPad’s 6-

For examples of intelligent communication and problem solving among orangutans, elephants, and killer whales, watch LaunchPad’s 6-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- If your dog barks at a stranger at the front door, does this qualify as language? What if the dog yips in a telltale way to let you know she needs to go out?

These are definitely communications. But if language consists of words and the grammatical rules we use to combine them to communicate meaning, few scientists would label a dog’s barking and yipping as language.

Thinking and Language

9-

Thinking and language intricately intertwine. Asking which comes first is one of psychology’s chicken-

linguistic determinism Whorf’s hypothesis that language determines the way we think.

Language Influences Thinking

Linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf (1956) contended that “language itself shapes a [person’s] basic ideas.” The Hopi, who have no past tense for their verbs, could not readily think about the past, said Whorf.

Whorf’s linguistic determinism hypothesis is too extreme. We all think about things for which we have no words. (Can you think of a shade of blue you cannot name?) And we routinely have unsymbolized (wordless, imageless) thoughts, as when someone, while watching two men carry a load of bricks, wondered whether the men would drop them (Heavey & Hurlburt, 2008; Hurlburt et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, to those who speak two dissimilar languages, such as English and Japanese, it seems obvious that a person may think differently in different languages (Brown, 1986). Unlike English, which has a rich vocabulary for self-

380

Depending on which emotion they want to express, bilingual parents will often switch languages. “When my mom gets angry at me, she’ll speak in Mandarin,” explained one Chinese-

So our words may not determine what we think, but they do influence our thinking (Boroditsky, 2011). We use our language in forming categories. In Brazil, the isolated Piraha people have words for the numbers 1 and 2, but numbers above that are simply “many.” Thus, if shown 7 nuts in a row, they find it difficult to lay out the same number from their own pile (Gordon, 2004).

Words also influence our thinking about colors. Whether we live in New Mexico, New South Wales, or New Guinea, we see colors much the same, but we use our native language to classify and remember them (Davidoff, 2004; Roberson et al., 2004, 2005). Imagine viewing three colors and calling two of them “yellow” and one of them “blue.” Later you would likely see and recall the yellows as being more similar. But if you speak the language of Papua New Guinea’s Berinmo tribe, which has words for two different shades of yellow, you would more speedily perceive and better recall the variations between the two yellows. And if your language is Russian, which has distinct names for various shades of blue, such as goluboy and siniy, you might recall the yellows as more similar and remember the blues better. Words matter.

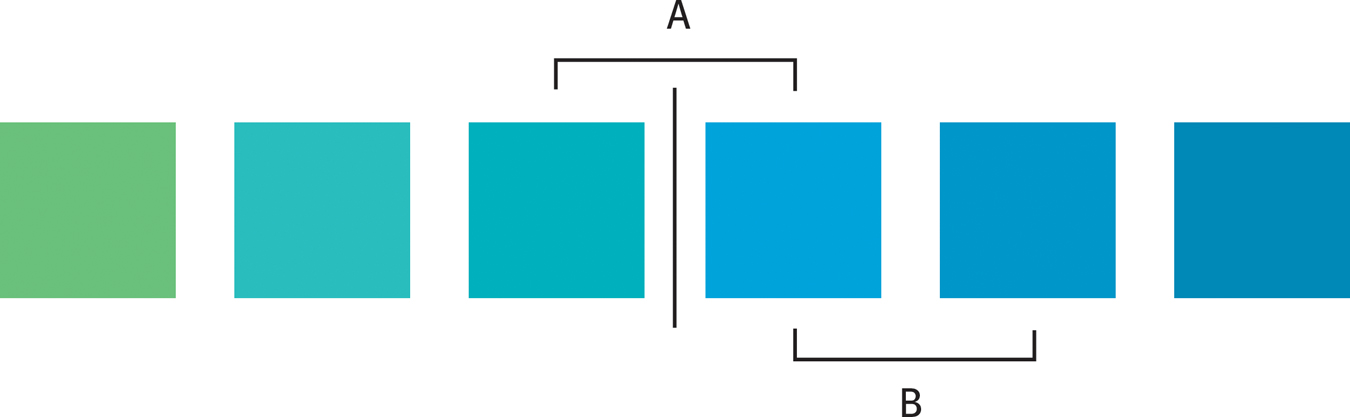

Perceived differences grow as we assign different names. On the color spectrum, blue blends into green—

Figure 9.11

Figure 9.11Language and perception When people view blocks of equally different colors, they perceive those with different names as more different. Thus the “green” and “blue” in contrast A may appear to differ more than the two equally different blues in contrast B (Özgen, 2004).

Given words’ subtle influence on thinking, we do well to choose our words carefully. Is “A child learns language as he interacts with his caregivers” any different from “Children learn language as they interact with their caregivers”? Many studies have found that it is. When hearing the generic he (as in “the artist and his work”) people are more likely to picture a male (Henley, 1989; Ng, 1990). If he and his were truly gender free, we shouldn’t skip a beat when hearing that “man, like other mammals, nurses his young.”

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.”

Henry Ward Beecher, Proverbs from Plymouth Pulpit, 1887

To expand language is to expand the ability to think. Children’s thinking develops hand in hand with their language (Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1986). Indeed, it is very difficult to think about or conceptualize certain abstract ideas (commitment, freedom, or rhyming) without language! And what is true for preschoolers is true for everyone: It pays to increase your word power. That’s why most textbooks, including this one, introduce new words—

381

Increased word power helps explain what McGill University researcher Wallace Lambert (1992; Lambert et al., 1993) has called the bilingual advantage. Bilingual people are skilled at inhibiting one language while using the other. And thanks to their well-

To consider how researchers have learned about the benefits of learning more than one language, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If There is a Bilingual Advantage?

Lambert helped devise a Canadian program that immerses English-

Whether we are in the linguistic minority or majority, language links us to one another. Language also connects us to the past and the future. “To destroy a people, destroy their language,” observed poet Joy Harjo.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Benjamin Lee Whorf’s controversial hypothesis, called ______________ ______________, suggested that we cannot think about things unless we have words for those concepts or ideas.

linguistic determinism

Thinking in Images

When you are alone, do you talk to yourself? Is “thinking” simply conversing with yourself? Without a doubt, words convey ideas. But sometimes ideas precede words. To turn on the cold water in your bathroom, in which direction do you turn the handle? To answer, you probably thought not in words but with implicit (nondeclarative, procedural) memory—

“When we see a person walking down the street talking to himself, we generally assume that he is mentally ill. But we all talk to ourselves continuously—

Sam Harris, “We Are Lost in Thought,” 2011

Indeed, we often think in images. Artists think in images. So do composers, poets, mathematicians, athletes, and scientists. Albert Einstein reported that he achieved some of his greatest insights through visual images and later put them into words. Pianist Liu Chi Kung harnessed the power of thinking in images. One year after placing second in the 1958 Tschaikovsky piano competition, Liu was imprisoned during China’s cultural revolution. Soon after his release, after seven years without touching a piano, he was back on tour. Critics judged Liu’s musicianship as better than ever. How did he continue to develop without practice? “I did practice,” said Liu, “every day. I rehearsed every piece I had ever played, note by note, in my mind” (Garfield, 1986).

For someone who has learned a skill, such as ballet dancing, even watching the activity will activate the brain’s internal simulation of it, reported one British research team after collecting fMRIs as people watched videos (Calvo-

One experiment on mental practice and basketball free-

382

Mental rehearsal can also help you achieve an academic goal, as researchers demonstrated with two groups of introductory psychology students facing a midterm exam one week later (Taylor et al., 1998). (Scores of other students, not engaging in any mental simulation, formed a control group.) The first group spent five minutes each day visualizing themselves scanning the posted grade list, seeing their A, beaming with joy, and feeling proud. This outcome simulation had little effect, adding only 2 points to their exam-

To experience your own thinking as (a) manipulating words and (b) manipulating images, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: My Head Is Spinning!

To experience your own thinking as (a) manipulating words and (b) manipulating images, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: My Head Is Spinning!

***

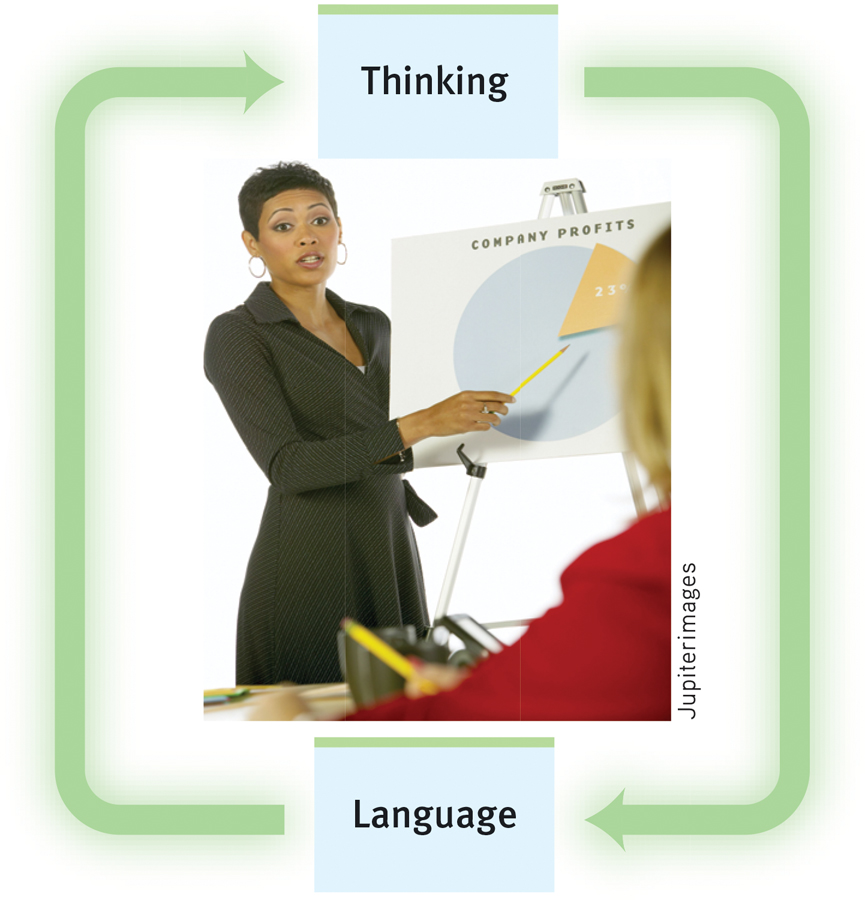

What, then, should we say about the relationship between thinking and language? As we have seen, language influences our thinking. But if thinking did not also affect language, there would never be any new words. And new words and new combinations of old words express new ideas. The basketball term slam dunk was coined after the act itself had become fairly common. Blogs became part of our language after web logs appeared. So, let us say that thinking affects our language, which then affects our thought (FIGURE 9.12).

Figure 9.12

Figure 9.12The interplay of thought and language The traffic runs both ways between thinking and language. Thinking affects our language, which affects our thought.

What time is it now? When we asked you (in the section on overconfidence) to estimate how quickly you would finish this chapter, did you underestimate or overestimate?

Psychological research on thinking and language mirrors the mixed impressions of our species by those in fields such as literature and religion. The human mind is simultaneously capable of striking intellectual failures and of striking intellectual power. Misjudgments are common and can have disastrous consequences. So we do well to appreciate our capacity for error. Yet our efficient heuristics often serve us well. Moreover, our ingenuity at problem solving and our extraordinary power of language mark humankind as almost “infinite in faculties.”

Question

G/SFzwfkPcqqbRJ7fVX2QyYHCtGbg5tll0V8Knz1gSpCPYikHaWwJaNzclR9M53LUVXsFj42+vt5hqcYVpmW/x91z/bLUUEiZgig/I27J9qM6eIscZ/+0eW9X9i3KYIiqpud3QMONj+zm4WXwW4SVqVVIlwiA2GByjbV0Xa0pkPl72wboqkGciktXC1qMgBgpdmUEzZ7l2GPPz5ZvmoPt5tCFlLYvJ8L8ZsPx1jT3+kQE7zT6PuJkwMQ7dWwu7Cu96LMG46kp7CVR8vQWgvIeg==RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is mental practice, and how can it help you to prepare for an upcoming event?

Mental practice uses visual imagery to mentally rehearse future behaviors, activating some of the same brain areas used during the actual behaviors. Visualizing the details of the process is more effective than visualizing only your end goal.

383