10.3 Influences on Drug Use

10-

Drug use by North American youth increased during the 1970s. Then, with increased drug education and a more realistic and deglamorized media depiction of taking drugs, drug use declined sharply (except for a small rise in the mid-

- In the University of Michigan’s annual survey of 15,000 U.S. high school seniors, the proportion who said there is “great risk” in regular marijuana use rose from 35 percent in 1978 to 79 percent in 1991, then retreated to 40 percent in 2013 (Johnston et al., 2014).

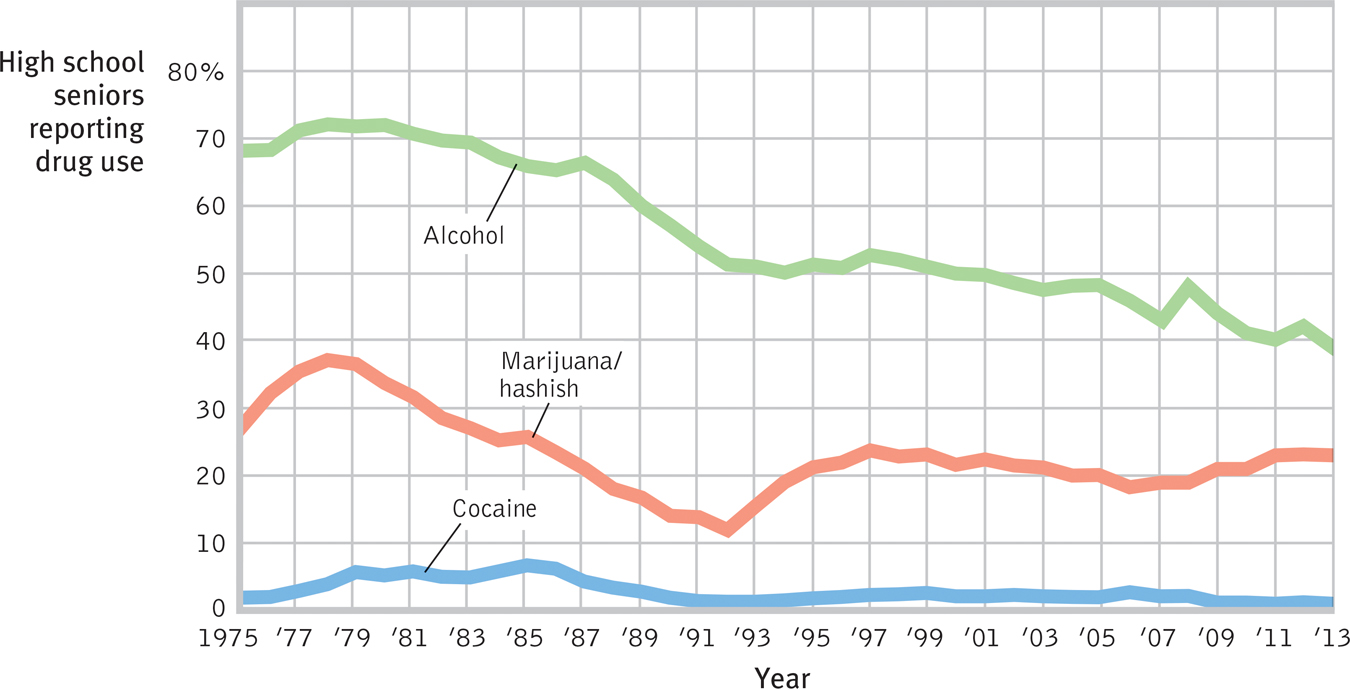

- After peaking in 1978, marijuana use by U.S. high school seniors declined through 1992, then rose, but has recently been holding steady (see FIGURE 10.6). Among Canadian 15-

to 24- year- olds, 23 percent report using marijuana monthly, weekly, or daily (Health Canada, 2012).

Figure 10.6

Figure 10.6Trends in drug use The percentage of U.S. high school seniors who report having used alcohol, marijuana, or cocaine during the past 30 days largely declined from the late 1970s to 1992, when it partially rebounded for a few years. (Data from Johnston et al., 2014.)

For some adolescents, occasional drug use represents thrill seeking. Why, though, do others become regular drug users? In search of answers, researchers have engaged biological, psychological, and social-

Biological Influences

Some people may be biologically vulnerable to particular drugs. For example, evidence accumulates that heredity influences some aspects of substance use problems, especially those appearing by early adulthood (Crabbe, 2002):

- Adopted individuals are more susceptible to alcohol use disorder if there is a history of it in one or both biological parents.

- Having an identical rather than fraternal twin with alcohol use disorder puts one at increased risk for alcohol problems (Kendler et al., 2002). In marijuana use also, identical twins more closely resemble each other than do fraternal twins.

- Boys who at age 6 are excitable, impulsive, and fearless (genetically influenced traits) are more likely as teens to smoke, drink, and use other drugs (Masse & Tremblay, 1997).

Warning signs of alcohol use disorder

- Drinking binges

- Craving alcohol

- Use results in unfulfilled work, school, or home tasks

- Failing to honor a resolve to drink less

- Continued use despite health risk

- Avoiding family or friends when drinking

- Researchers have bred rats and mice that prefer alcoholic drinks to water. One such strain has reduced levels of the brain chemical NPY. Mice engineered to overproduce NPY are very sensitive to alcohol’s sedating effect and drink little (Thiele et al., 1998).

- Researchers have identified genes that are more common among people and animals predisposed to alcohol use disorder, and they are seeking genes that contribute to tobacco addiction (Stacey et al., 2012). These culprit genes seemingly produce deficiencies in the brain’s natural dopamine reward system: While triggering temporary dopamine-produced pleasure, the addictive drugs disrupt normal dopamine balance. Studies of how drugs reprogram the brain’s reward systems raise hopes for anti-addiction drugs that might block or blunt the effects of alcohol and other drugs (Miller, 2008; Wilson & Kuhn, 2005).

Biological influences on drug use extend to other drugs as well. One study tracked 18,115 Swedish adoptees. Those with drug-

Psychological and Social-Cultural Influences

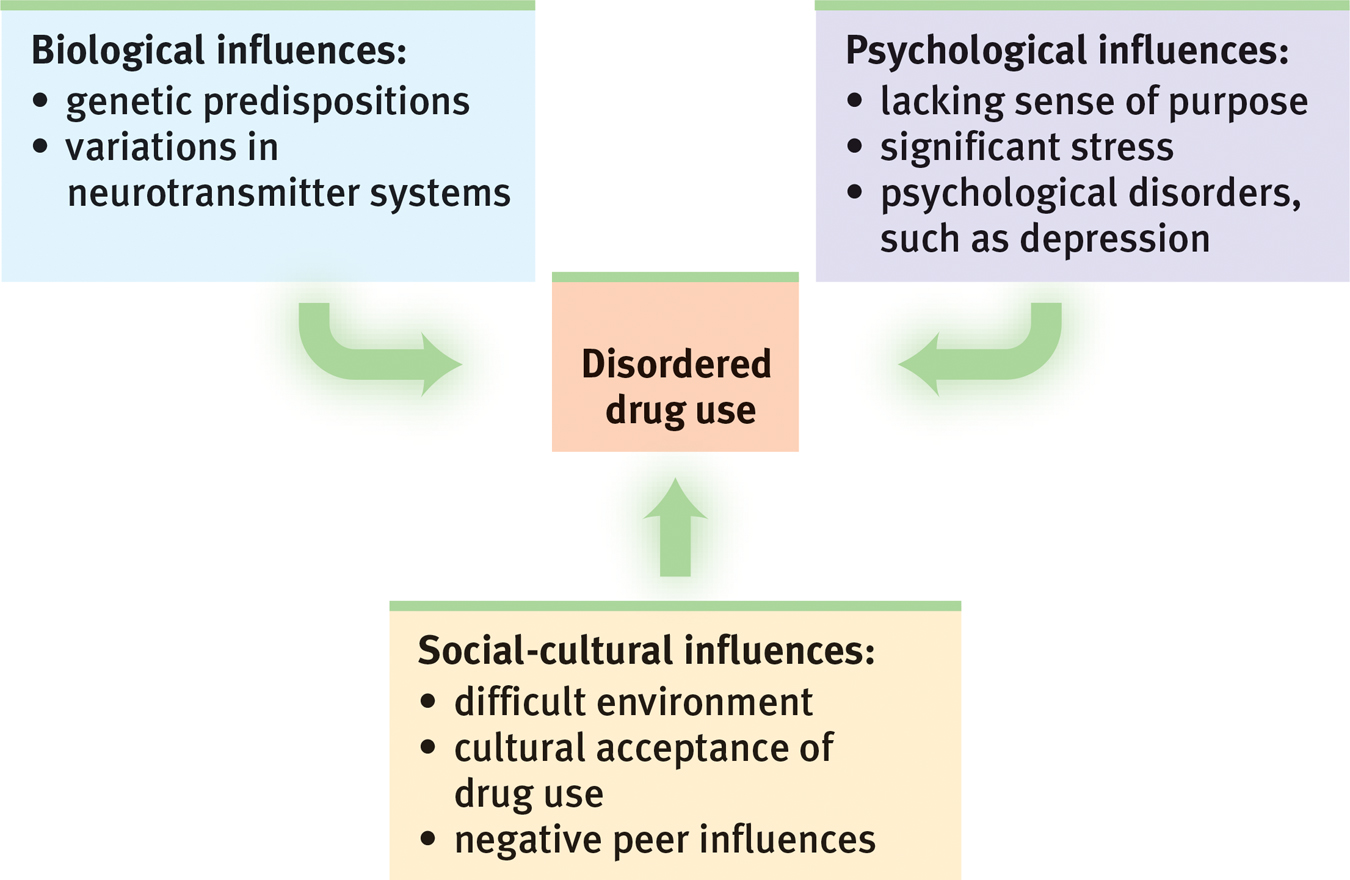

Throughout this text, we see that biological, psychological, and social-

Figure 10.7

Figure 10.7Levels of analysis for disordered drug use The biopsychosocial approach enables researchers to investigate disordered drug use from complementary perspectives.

Sometimes the psychological influence is obvious. Many heavy users of alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine have experienced significant stress or failure and are depressed. Girls with a history of depression, eating disorders, or sexual or physical abuse are at risk for substance addiction. So are youth undergoing school or neighborhood transitions (CASA, 2003; Logan et al., 2002). Collegians who have not yet achieved a clear identity are also at greater risk (Bishop et al., 2005). By temporarily dulling the pain of self-

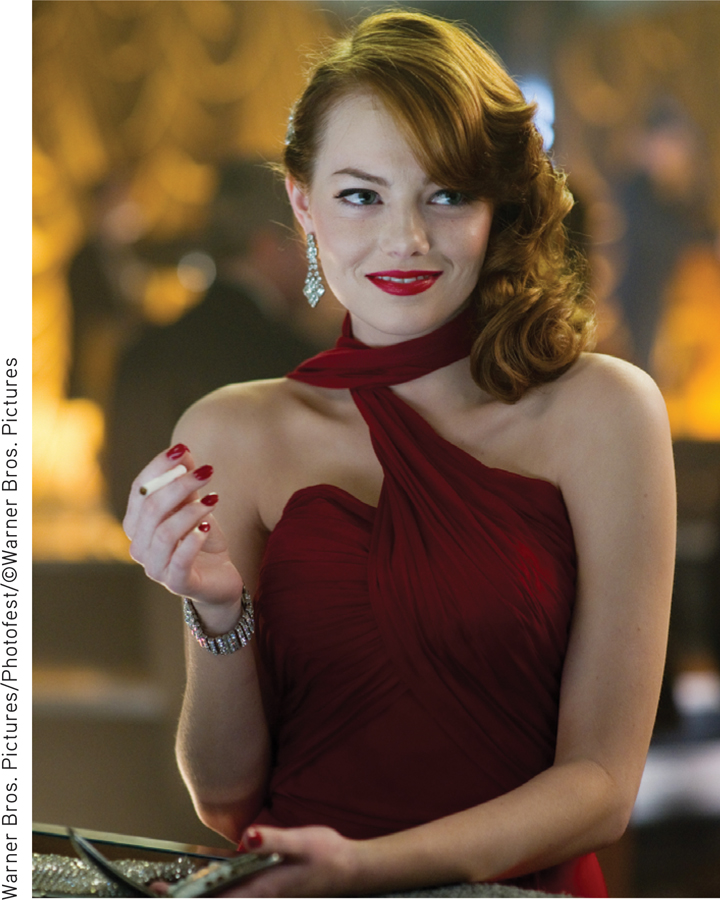

Smoking usually begins during early adolescence. (If you are in college or university, and the cigarette manufacturers haven’t yet made you their devoted customer, they almost surely never will.) Adolescents, self-

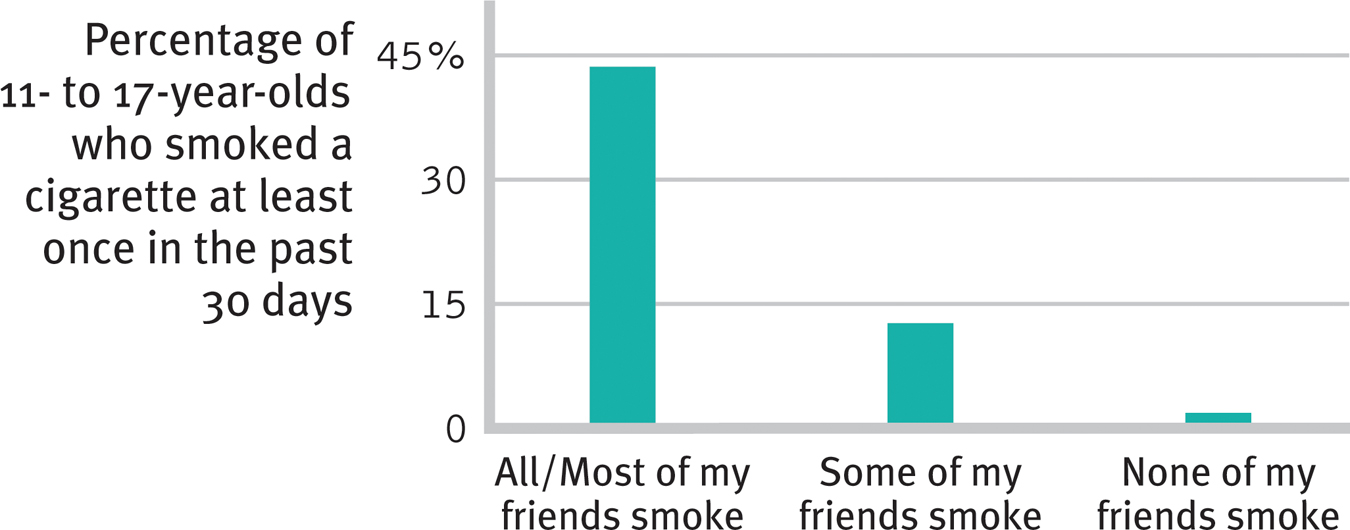

Figure 10.8

Figure 10.8Peer influence Kids don’t smoke if their friends don’t (Philip Morris, 2003). A correlation-

Rates of drug use also vary across cultural and ethnic groups. One survey of 100,000 teens in 35 European countries found that marijuana use in the prior 30 days ranged from zero to 1 percent in Romania and Sweden to 20 to 22 percent in Britain, Switzerland, and France (ESPAD, 2003). Independent U.S. government studies of drug use in households nationwide and among high schoolers in all regions reveal that African-

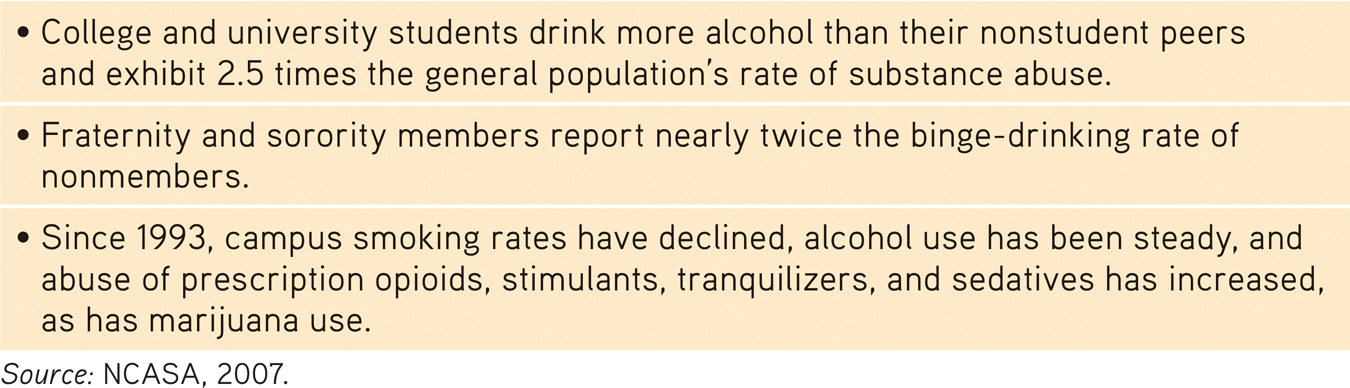

Whether in cities or rural areas, peers influence attitudes about drugs. They also throw the parties and provide (or don’t provide) the drugs. If an adolescent’s friends use drugs, the odds are that he or she will, too. If the friends do not, the opportunity may not even arise. Teens who come from happy families, who do not begin drinking before age 15, and who do well in school tend not to use drugs, largely because they rarely associate with those who do (Bachman et al., 2007; Hingson et al., 2006; Odgers et al., 2008).

Peer influence is more than what friends do or say. Adolescents’ expectations—

Table 10.3

Table 10.3Facts About “Higher” Education

People whose beginning use of drugs was influenced by their peers are more likely to stop using when friends stop or their social network changes (Kandel & Raveis, 1989). One study that followed 12,000 adults over 32 years found that smokers tend to quit in clusters (Christakis & Fowler, 2008). Within a social network, the odds of a person quitting increased when a spouse, friend, or co-

As always with correlations, the traffic between friends’ drug use and our own may be two-

What do the findings on drug use suggest for drug prevention and treatment programs? Three channels of influence seem possible:

- Educate young people about the long-term costs of a drug’s temporary pleasures.

- Help young people find other ways to boost their self-esteem and purpose in life.

- Attempt to modify peer associations or to “inoculate” youths against peer pressures by training them in refusal skills.

People rarely abuse drugs if they understand the physical and psychological costs, feel good about themselves and the direction their lives are taking, and are in a peer group that disapproves of using drugs. These educational, psychological, and social-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why do tobacco companies try so hard to get customers hooked as teens?

Nicotine is powerfully addictive, expensive, and deadly. Those who start paving the neural pathways when young may find it very hard to stop using nicotine. As a result, tobacco companies may have lifelong customers.

- Studies have found that people who begin drinking in their early teens are much more likely to develop alcohol use disorder than those who begin at age 21 or after. What possible explanations might there be for this correlation?

Possible explanations include (a) a biological predisposition to both early use and later abuse; (b) brain changes and taste preferences triggered by early use; and (c) enduring habits, attitudes, activities, or peer relationships that foster alcohol misuse.