12.2 Evolutionary Success Helps Explain Similarities

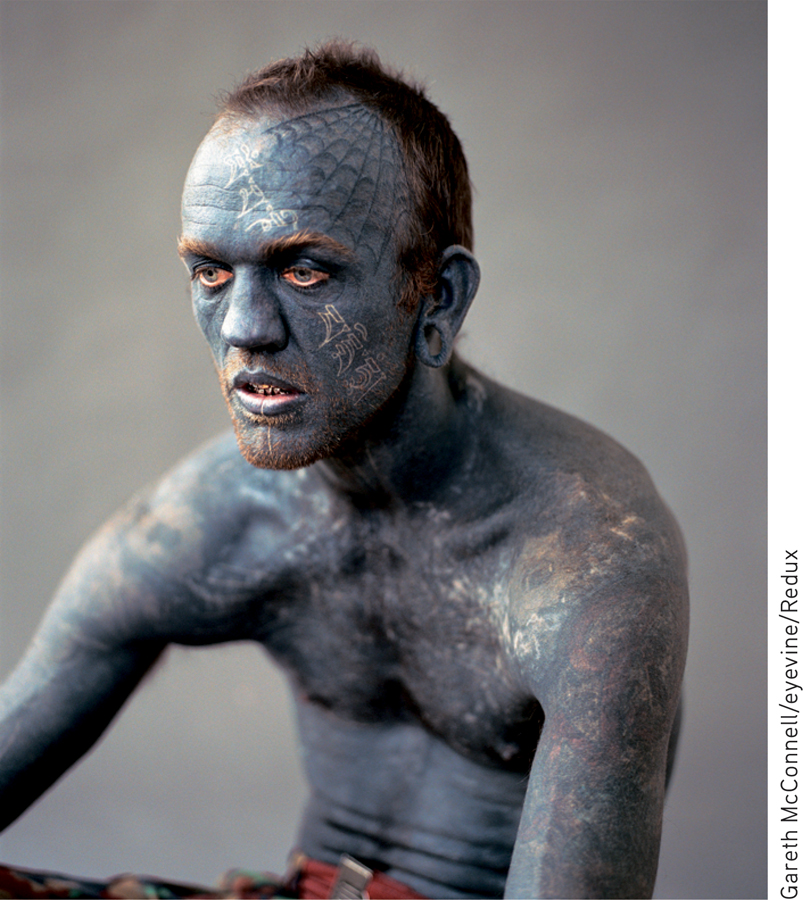

Human differences grab our attention. The Guinness World Records entertains us with the height of the tallest-ever human, the oldest living person, and the person with the most tattoos. But our deep similarities also demand explanation. In the big picture, our lives are remarkably alike. Visit the international arrivals area at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, a world hub where arriving passengers meet their excited loved ones. There you will see the same delighted joy in the faces of Indonesian grandmothers, Chinese children, and homecoming Dutch. Evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker (2002, p. 73) has noted that it is no wonder our emotions, drives, and reasoning “have a common logic across cultures”: Our shared human traits “were shaped by natural selection acting over the course of human evolution.”

Our Genetic Legacy

Our behavioral and biological similarities arise from our shared human genome, our common genetic profile. No more than 5 percent of the genetic differences among humans arise from population group differences. Some 95 percent of genetic variation exists within populations (Rosenberg et al., 2002). The typical genetic difference between two Icelandic villagers or between two Kenyans is much greater than the average difference between the two groups. Thus, if after a worldwide catastrophe only Icelanders or Kenyans survived, the human species would suffer only “a trivial reduction” in its genetic diversity (Lewontin, 1982).

And how did we develop this shared human genome? At the dawn of human history, our ancestors faced certain questions: Who is my ally, who is my foe? With whom should I mate? What food should I eat? Some individuals answered those questions more successfully than others. For example, women who experienced nausea in the critical first three months of pregnancy were genetically predisposed to avoid certain bitter, strongly flavored, and novel foods. Avoiding such foods has survival value, since they are the very foods most often toxic to prenatal development (Profet, 1992; Schmitt & Pilcher, 2004). Early humans disposed to eat nourishing rather than poisonous foods survived to contribute their genes to later generations. Those who deemed leopards “nice to pet” often did not.

Similarly successful were those whose mating helped them produce and nurture offspring. Over generations, the genes of individuals not so disposed tended to be lost from the human gene pool. As success-enhancing genes continued to be selected, behavioral tendencies and thinking and learning capacities emerged that prepared our Stone Age ancestors to survive, reproduce, and send their genes into the future, and into you.

Despite high infant mortality and rampant disease in past millennia, not one of your countless ancestors died childless.

Across our cultural differences, we even share a “universal moral grammar” (Mikhail, 2007). Men and women, young and old, liberal and conservative, living in Sydney or Seoul, all respond negatively when asked, “If a lethal gas is leaking into a vent and is headed toward a room with seven people, is it okay to push someone into the vent— saving the seven but killing the one?” And they all respond more approvingly when asked if it’s okay to allow someone to fall into the vent, again sacrificing one life but saving seven. Our shared moral instincts survive from a distant past where we lived in small groups in which direct harm-doing was punished. For all such universal human tendencies, from our intense need to give parental care, to our shared fears and lusts, evolutionary theory proposes a one-stop-shopping explanation (Schloss, 2009).

As inheritors of this prehistoric legacy, we are genetically predisposed to behave in ways that promoted our ancestors’ surviving and reproducing. But in some ways, we are biologically prepared for a world that no longer exists. We love the taste of sweets and fats, nutrients that prepared our physically active ancestors to survive food shortages. But few of us now hunt and gather our food. Too often, we search for sweets and fats in fast-food outlets and vending machines. Our natural dispositions, rooted deep in history, are mismatched with today’s junk-food and often inactive lifestyle.

Evolutionary Psychology Today

Those who are troubled by an apparent conflict between scientific and religious accounts of human origins may find it helpful to consider that different perspectives of life can be complementary. For example, the scientific account attempts to tell us when and how; religious creation stories usually aim to tell about an ultimate who and why. As Galileo explained to the Grand Duchess Christina, “The Bible teaches how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go.”

Darwin’s theory of evolution has become one of biology’s organizing principles. “Virtually no contemporary scientists believe that Darwin was basically wrong,” noted Jared Diamond (2001). Today, Darwin’s theory lives on in the second Darwinian revolution, the application of evolutionary principles to psychology. In concluding On the Origin of Species, Darwin (1859, p. 346) anticipated this, foreseeing “open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation.”

Elsewhere in this text, we address questions that intrigue evolutionary psychologists: Why do infants start to fear strangers about the time they become mobile? Why are biological fathers so much less likely than unrelated boyfriends to abuse and murder the children with whom they share a home? Why do so many more people have phobias about spiders, snakes, and heights than about more dangerous threats, such as guns and electricity? And why do we fear air travel so much more than driving?

To see how evolutionary psychologists think and reason, let’s pause to explore their answers to two questions: How are males and females alike? How and why does their sexuality differ?