13.1 How Does Experience Influence Development?

Our genes, when expressed in specific environments, influence our developmental differences. We are not “blank slates” (Kenrick et al., 2009). We are more like coloring books, with certain lines predisposed and experience filling in the full picture. We are formed by nature and nurture. But what are the most influential components of our nurture? How do our early experiences, our family and peer relationships, and all our other experiences guide our development and contribute to our diversity?

The formative nurture that conspires with nature begins at conception, with the prenatal environment in the womb, where embryos receive differing nutrition and varying levels of exposure to toxic agents. Nurture then continues outside the womb, where our early experiences foster brain development.

Experience and Brain Development

13-

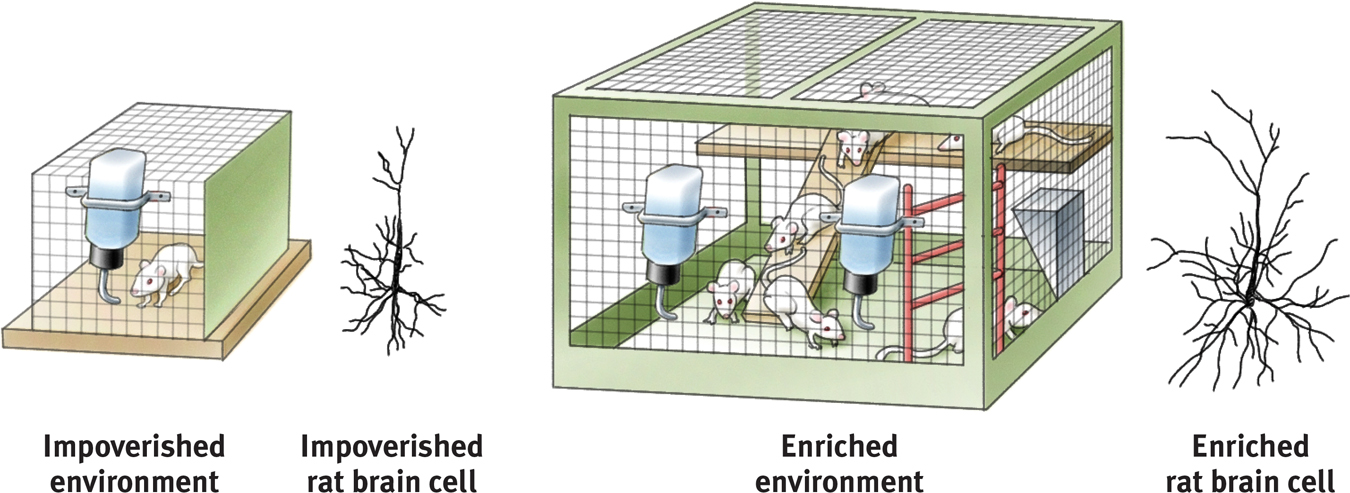

Our genes dictate our overall brain architecture, but experience fills in the details. Developing neural connections prepare our brain for thought, language, and other later experiences. So how do early experiences leave their “fingerprints” in the brain? Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) opened a window on that process when they raised some young rats in solitary confinement and others in a communal playground. When they later analyzed the rats’ brains, those who died with the most toys had won. The rats living in the enriched environment, which simulated a natural environment, usually developed a heavier and thicker brain cortex (FIGURE 13.1).

Figure 13.1

Figure 13.1Experience affects brain development Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) raised rats either alone in an environment without playthings, or with other rats in an environment enriched with playthings changed daily. In 14 of 16 repetitions of this basic experiment, rats in the enriched environment developed significantly more cerebral cortex (relative to the rest of the brain’s tissue) than did those in the impoverished environment.

Rosenzweig was so surprised by this discovery that he repeated the experiment several times before publishing his findings (Renner & Rosenzweig, 1987; Rosenzweig, 1984). So great are the effects that, shown brief video clips of rats, you could tell from their activity and curiosity whether their environment had been impoverished or enriched (Renner & Renner, 1993). After 60 days in the enriched environment, the rats’ brain weights increased 7 to 10 percent and the number of synapses mushroomed by about 20 percent (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998).

Such results have motivated improvements in environments for laboratory, farm, and zoo animals—

Nature and nurture interact to sculpt our synapses. Brain maturation provides us with an abundance of neural connections. Experiences trigger sights and smells, touches and tugs, and activate and strengthen connections. Unused neural pathways weaken. Like forest pathways, popular tracks are broadened and less-

Here at the juncture of nurture and nature is the biological reality of early childhood learning. During early childhood—

“Genes and experiences are just two ways of doing the same thing—wiring synapses.”

Joseph LeDoux, The Synaptic Self, 2002

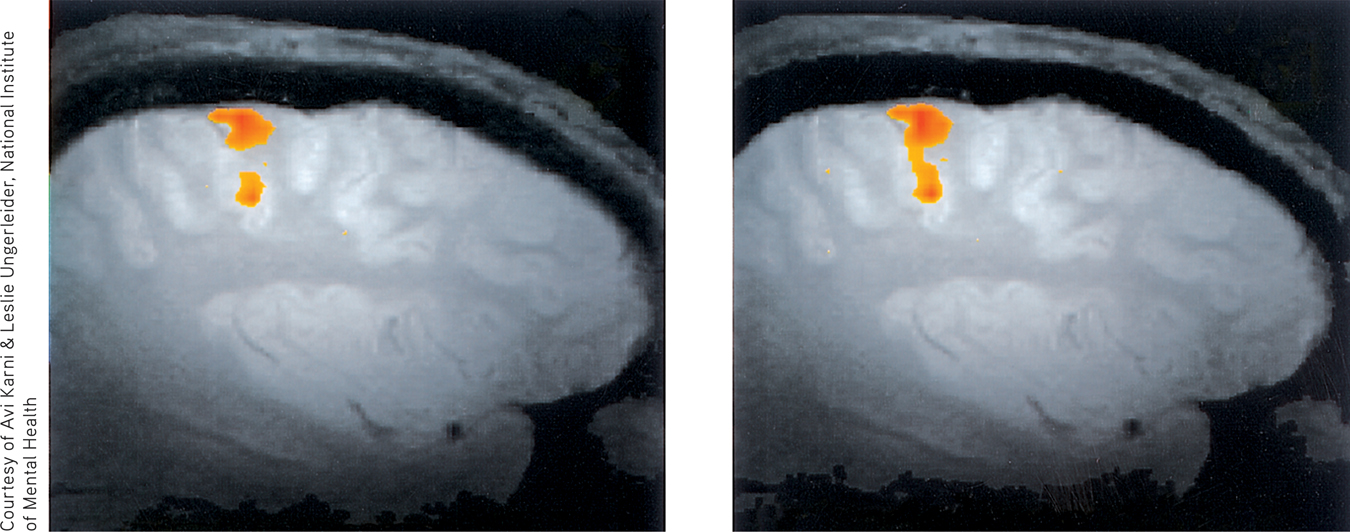

Although normal stimulation during the early years is critical, the brain’s development does not end with childhood. Thanks to the brain’s amazing plasticity, our neural tissue is ever changing and reorganizing in response to new experiences. New neurons are also born. If a monkey pushes a lever with the same finger many times a day, brain tissue controlling that finger will change to reflect the experience (FIGURE 13.2). Human brains work similarly. Whether learning to keyboard, skateboard, or navigate London’s streets, we perform with increasing skill as our brain incorporates the learning (Ambrose, 2010; Maguire et al., 2000).

Figure 13.2

Figure 13.2A trained brain A well-

How Much Credit or Blame Do Parents Deserve?

13-

In procreation, a woman and a man shuffle their gene decks and deal a life-

But do parents really produce future adults with an inner wounded child by being (take your pick from the toxic-

Parents do matter. But parenting wields its largest effects at the extremes: the abused children who become abusive, the neglected who become neglectful, the loved but firmly handled who become self-

Yet in personality measures, shared environmental influences from the womb onward typically account for less than 10 percent of children’s differences. In the words of behavior geneticists Robert Plomin and Denise Daniels (1987; Plomin, 2011), “Two children in the same family are [apart from their shared genes] as different from one another as are pairs of children selected randomly from the population.” To developmental psychologist Sandra Scarr (1993), this implied that “parents should be given less credit for kids who turn out great and blamed less for kids who don’t.” Knowing children are not easily sculpted by parental nurture, perhaps parents can relax a bit more and love their children for who they are.

Peer Influence

As children mature, what other experiences do the work of nurturing? At all ages, but especially during childhood and adolescence, we seek to fit in with our groups (Harris, 1998, 2000):

“Men resemble the times more than they resemble their fathers.”

Ancient Arab proverb

- Preschoolers who disdain a certain food often will eat that food if put at a table with a group of children who like it.

- Children who hear English spoken with one accent at home and another in the neighborhood and at school will invariably adopt the accent of their peers, not their parents. Accents (and slang) reflect culture, “and children get their culture from their peers,” as Judith Rich Harris (2007), has noted.

- Teens who start smoking typically have friends who model smoking, suggest its pleasures, and offer cigarettes (J. S. Rose et al., 1999; R. J. Rose et al., 2003). Part of this peer similarity may result from a selection effect, as kids seek out peers with similar attitudes and interests. Those who smoke (or don’t) may select as friends those who also smoke (or don’t).

- Put two teens together and their brains become hypersensitive to reward (Albert et al., 2013). This increased activation helps explain why teens take more driving risks when with friends than they do when alone (Chein et al., 2011).

Howard Gardner (1998) has concluded that parents and peers are complementary:

Parents are more important when it comes to education, discipline, responsibility, orderliness, charitableness, and ways of interacting with authority figures. Peers are more important for learning cooperation, for finding the road to popularity, for inventing styles of interaction among people of the same age. Youngsters may find their peers more interesting, but they will look to their parents when contemplating their own futures. Moreover, parents [often] choose the neighborhoods and schools that supply the peers.

This power to select a child’s neighborhood and schools gives parents an ability to influence the culture that shapes the child’s peer group. And because neighborhood influences matter, parents may want to become involved in intervention programs that aim at a whole school or neighborhood. If the vapors of a toxic climate are seeping into a child’s life, that climate—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the selection effect, and how might it affect a teen’s decision to drink alcohol?

Adolescents tend to select out similar others and sort themselves into like-