13.2 Cultural Influences

13-

Compared with the narrow path taken by flies, fish, and foxes, the road along which environment drives us is wider. The mark of our species—

Culture is the behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next (Brislin, 1988; Cohen, 2009). Human nature, noted Roy Baumeister (2005), seems designed for culture. We are social animals, but more. Wolves are social animals; they live and hunt in packs. Ants are incessantly social, never alone. But “culture is a better way of being social,” noted Baumeister. Wolves function pretty much as they did 10,000 years ago. You and I enjoy things unknown to most of our century-

Other animals exhibit smaller kernels of culture. Primates have local customs of tool use, grooming, and courtship. Chimpanzees sometimes invent customs using leaves to clean their bodies, slapping branches to get attention, and doing a “rain dance” by slowly displaying themselves at the start of rain and pass them on to their peers and offspring (Whiten et al., 1999). Culture supports a species’ survival and reproduction by transmitting learned behaviors that give a group an edge. But human culture does more.

Thanks to our mastery of language, we humans enjoy the preservation of innovation. Within the span of this day, we have used Google, laser printers, digital hearing technology [DM], and a GPS running watch [ND]. On a grander scale, we have culture’s accumulated knowledge to thank for the last century’s 30-

Across cultures, we differ in our language, our monetary systems, our sports, even which side of the road we drive on. But beneath these differences is our great similarity—

Variation Across Cultures

We see our adaptability in cultural variations among our beliefs and our values, in how we nurture our children and bury our dead, and in what we wear (or whether we wear anything at all). We are ever mindful that the readers of this book are culturally diverse. You and your ancestors reach from Australia to Africa and from Singapore to Sweden.

Riding along with a unified culture is like running with the wind: As it carries us along, we hardly notice it is there. When we try running against the wind we feel its force. Face to face with a different culture, we become aware of the cultural winds. Visiting Europe, most North Americans notice the smaller cars, the left-

But humans in varied cultures nevertheless share some basic moral ideas. Even before they can walk, babies prefer helpful people over naughty ones (Hamlin et al., 2011). Yet each cultural group also evolves its own norms—rules for accepted and expected behavior. The British have a norm for orderly waiting in line. Many South Asians use only the right hand’s fingers for eating. Sometimes social expectations seem oppressive: “Why should it matter how I dress?” Yet, norms grease the social machinery and free us from self-

When cultures collide, their differing norms often befuddle. Should we greet people by shaking hands, bowing, or kissing each cheek? Knowing what sorts of gestures and compliments are culturally appropriate, we can relax and enjoy one another without fear of embarrassment or insult.

When we don’t understand what’s expected or accepted, we may experience culture shock. People from Mediterranean cultures have perceived northern Europeans as efficient but cold and preoccupied with punctuality (Triandis, 1981). People from time-

Variation Over Time

Like biological creatures, cultures vary and compete for resources, and thus evolve over time (Mesoudi, 2009). Consider how rapidly cultures may change. English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (1342–

But some changes seem not so wonderfully positive. Had you fallen asleep in the United States in 1960 and awakened today, you would open your eyes to a culture with more divorce and depression. You would also find North Americans—

Whether we love or loathe these changes, we cannot fail to be impressed by their breathtaking speed. And we cannot explain them by changes in the human gene pool, which evolves far too slowly to account for high-

Culture and the Self

13-

Imagine that someone ripped away your social connections, making you a solitary refugee in a foreign land. How much of your identity would remain intact?

If you are an individualist, a great deal of your identity would remain intact. You would have an independent sense of “me,” and an awareness of your unique personal convictions and values. Individualists give higher priority to personal goals. They define their identity mostly in terms of personal traits. They strive for personal control and individual achievement.

Individualism is valued in most areas of North America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. The United States is mostly an individualist culture. Founded by settlers who wanted to differentiate themselves from others, Americans have cherished the “pioneer” spirit (Kitayama et al., 2010). Some 85 percent of Americans say it is possible “to pretty much be who you want to be” (Sampson, 2000).

Individualists share the human need to belong. They join groups. But they are less focused on group harmony and doing their duty to the group (Brewer & Chen, 2007). Being more self-

Although individuals within cultures vary, different cultures emphasize either individualism or collectivism. If set adrift in a foreign land as a collectivist, you might experience a greater loss of identity. Cut off from family, groups, and loyal friends, you would lose the connections that have defined who you are. Group identifications provide a sense of belonging, a set of values, and an assurance of security in collectivist cultures. In return, collectivists have deeper, more stable attachments to their groups—

“One needs to cultivate the spirit of sacrificing the little me to achieve the benefits of the big me.”

Chinese saying

Collectivists are like athletes who take more pleasure in their team’s victory than in their own performance. They find satisfaction in advancing their groups’ interests, even at the expense of personal needs. Preserving group spirit and avoiding social embarrassment are important goals. Collectivists therefore avoid direct confrontation, blunt honesty, and uncomfortable topics. They value humility, not self-

To be sure, there is diversity within cultures. Within many countries, there are also distinct subcultures related to one’s religion, economic status, and region (Cohen, 2009). In China, greater collectivist thinking occurs in provinces that produce large amounts of rice, a difficult-

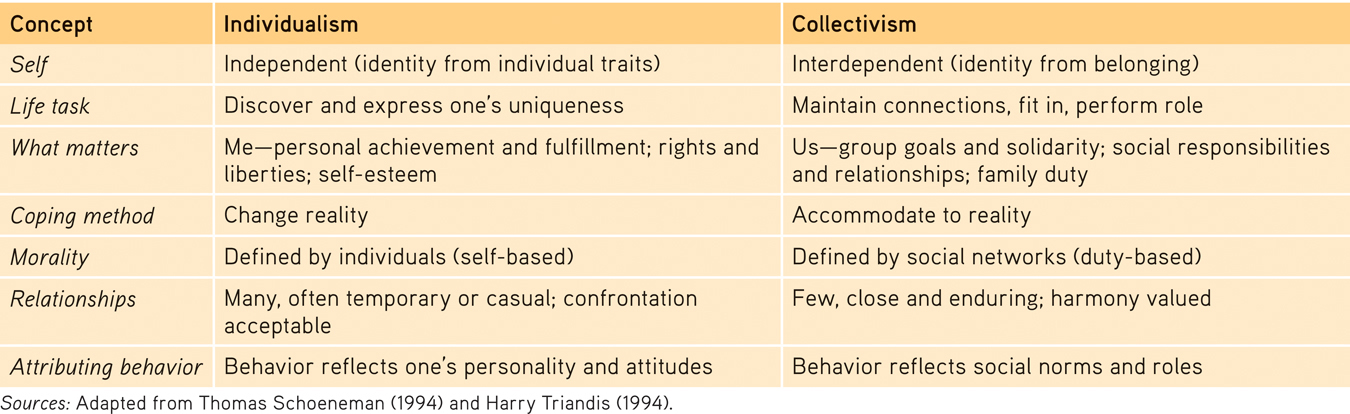

Table 13.1

Table 13.1Value Contrasts Between Individualism and Collectivism

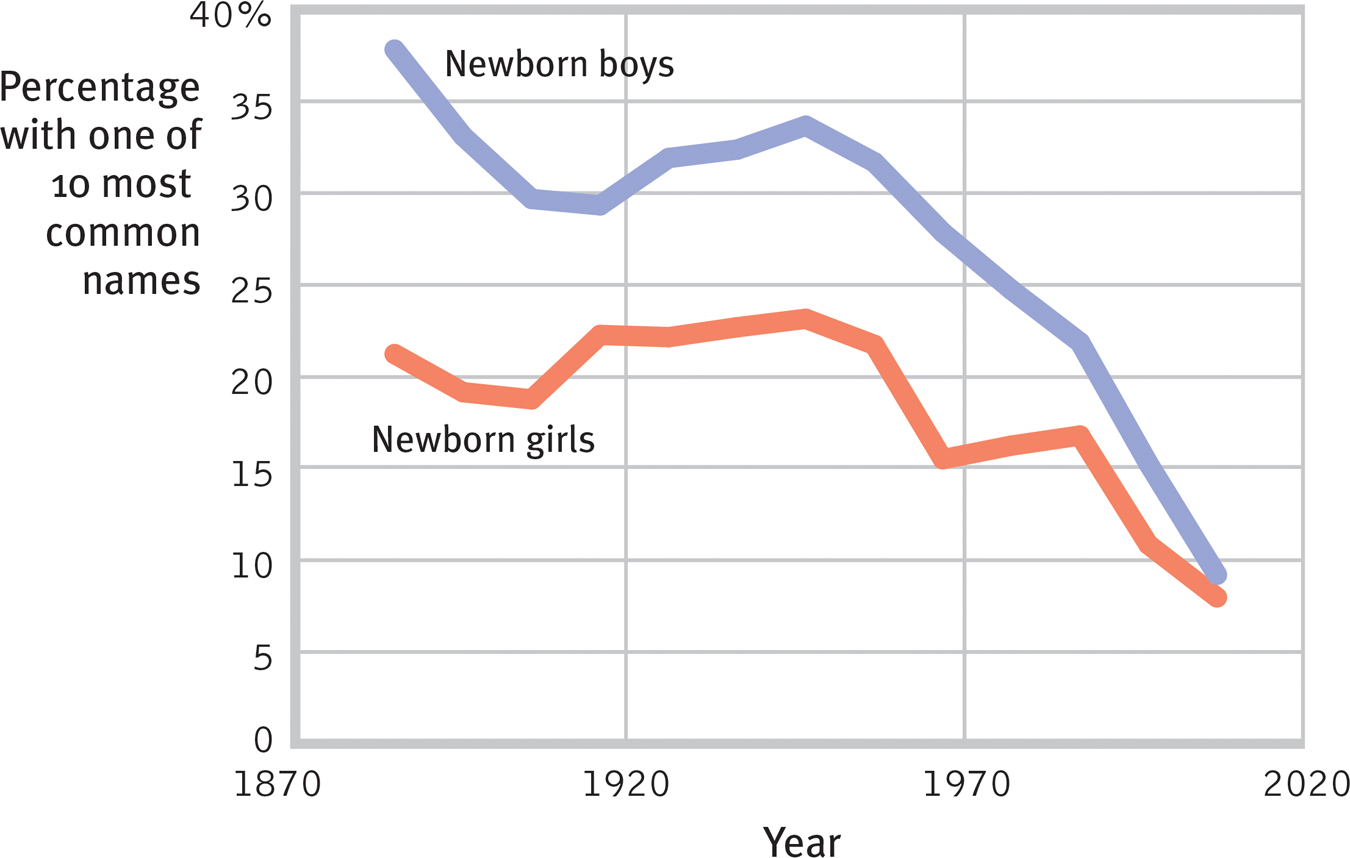

Individualists even prefer unusual names, as psychologist Jean Twenge noticed while seeking a name for her first child. Over time, the most common American names listed by year on the U.S. Social Security baby names website were becoming less desirable. When she and her colleagues (2010) analyzed the first names of 325 million American babies born between 1880 and 2007, they confirmed this trend. As FIGURE 13.3 illustrates, the percentage of boys and girls given one of the 10 most common names for their birth year has plunged, especially in recent years. Even within the United States, parents from more recently settled states (for example, Utah and Arizona) give their children more distinct names compared with parents who live in more established states (for example, New York and Massachusetts) (Varnum & Kitayama, 2011).

Figure 13.3

Figure 13.3A child like no other Americans’ individualist tendencies are reflected in their choice of names for their babies. In recent years, the percentage of American babies receiving one of that year’s 10 most common names has plunged. (Data from Twenge et al., 2010.)

The individualist–

There has been more loneliness, divorce, homicide, and stress-

As cultures evolve, some trends weaken and others grow stronger. In Western cultures, individualism increased strikingly over the last century. This trend reached a new high in 2012, when U.S. high school and college students reported the greatest-

What predicts changes in one culture over time, or between differing cultures? Social history matters. In Western cultures, individualism and independence have been fostered by voluntary migration, a capitalist economy, and a sparsely populated, challenging environment (Kitayama et al., 2009, 2010; Varnum et al., 2010). Might biology also play a role? In search of biological underpinnings to such cultural differences—

Culture and Child Raising

Child-

Children across place and time have thrived under various child-

Many Asians and Africans live in cultures that value emotional closeness. Infants and toddlers may sleep with their mothers and spend their days close to a family member (Morelli et al., 1992; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). These cultures encourage a strong sense of family self—a feeling that what shames the child shames the family, and what brings honor to the family brings honor to the self.

In the African Gusii society, babies nurse freely but spend most of the day on their mother’s back—

Developmental Similarities Across Groups

Mindful of how others differ from us, we often fail to notice the similarities predisposed by our shared biology. One 49-

Actually, compared with the person-

Even differences within a culture, such as those sometimes attributed to race, are often easily explained by an interaction between our biology and our culture. David Rowe and his colleagues (1994, 1995) illustrated this with an analogy: Black men tend to have higher blood pressure than White men. Suppose that (1) in both groups, salt consumption correlates with blood pressure, and (2) salt consumption is higher among Black men than among White men. The blood pressure “race difference” might then actually be, at least partly, a diet difference—

And that, said Rowe and his colleagues, parallels psychological findings. Although Latino, Asian, Black, White, and Native Americans differ in school achievement and delinquency, the differences are “no more than skin deep.” To the extent that family structure, peer influences, and parental education predict behavior in one of these ethnic groups, they do so for the others as well.

So as members of different ethnic and cultural groups, we may differ in surface ways. But as members of one species we seem subject to the same psychological forces. Our languages vary, yet they reflect universal principles of grammar. Our tastes vary, yet they reflect common principles of hunger. Our social behaviors vary, yet they reflect pervasive principles of human influence. Cross-

“When [someone] has discovered why men in Bond Street wear black hats he will at the same moment have discovered why men in Timbuctoo wear red feathers.”

G. K. Chesterton, Heretics, 1905

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do individualist and collectivist cultures differ?

Individualists give priority to personal goals over group goals and tend to define their identity in terms of their own personal attributes. Collectivists give priority to group goals over individual goals and tend to define their identity in terms of group identifications.